By Dirk Schoenmaker, Dean of the Duisenberg School of Finance and Professor of Finance, Banking and Insurance at the VU University Amsterdam. Originally published at VoxEU.

Debt financing amplifies the effects of asset prices fluctuations across the financial system and this can produce bubbles. Regulation therefore increasingly focusses on restricting debt financing. Although there is no silver bullet for making the financial system failure-proof, this column argues that policymakers should adopt an integrated and consistent macroprudential approach across the financial system in order to help prevent businesses moving to less-regulated pastures.

In an unusual call for regulation, CEOs of major financial institutions urged action on the asset bubble fear earlier this week (World Economic Forum 2015). They ask for a concerted macroprudential approach that addresses potential asset bubbles fuelled by current low interest rates. Without such a concerted approach, finance just moves to the least regulated segments of the financial system. Peter Wierts and I fully agree with their analysis.

There are various financial accelerator or amplification mechanisms at work in the financial system. The basic mechanism is that debt financing (‘leverage’) is increased to maximise profits during good times, when asset values (‘collateral’) are high and measured risk is low. A first example is banks, which expand their business with high levels of debt during good times (Adrian and Shin 2010). Another example is housing finance, where increasingly large mortgages are granted during a housing boom (Almeida et al. 2006). Finally, financial markets can also be pro-cyclical when ‘haircuts’ for securities financing transactions are reduced in good times (Brunnermeier and Pedersen 2009).

Financial institutions do not internalise the second round effects of debt-based finance on prices (leading to asset price bubbles) and quantities (leading to resource misalignments). It leads to an excessive pro-cyclical effect – as measured by the financial cycle – and externalities that form the main justification for macroprudential policy interventions. Different measures have therefore been proposed or implemented such as the countercyclical capital buffer and a leverage ratio (for banks), maximum loan-to-value ratios (for mortgages) and haircut floors on securities financing transactions. All these measures address the same underlying problem. An integrated approach is needed for effectively addressing it.

Amplification Mechanism

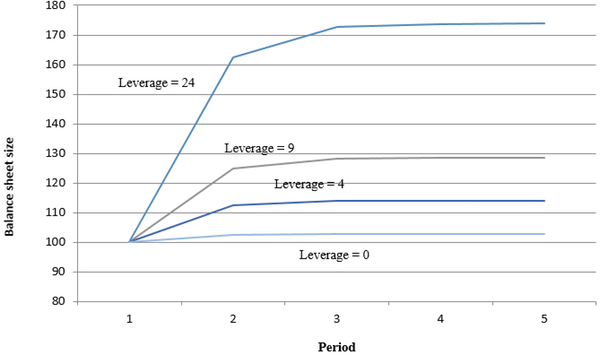

In Schoenmaker and Wierts (2015), we use a stylised model that highlights how debt financing (or leverage) amplifies the effects of asset price fluctuations on balance sheets and markets. Figure 1 illustrates the results. For an assumed asset price growth of 2.5%, it shows how higher leverage (measured in this case as debt divided by equity) strongly increases the eventual effect on balance sheet size. This occurs given that leverage amplifies the effects of asset price increases on the value of equity. This higher equity value allows further debt financing to increase return on equity. The balance sheet grows in this repeated process of equity and debt expansion. Restricting maximum permissible leverage would dampen such amplification, while countercyclical adjustment to maximum leverage could – in theory – stabilise the financial cycle (Gersbach and Rochet 2014).

Figure 1. Illustration of balance sheet growth with leverage and feedback on asset prices1

Therefore, regulators are increasingly imposing limits to leverage in some parts of the financial system (but not all). Some segments are already subject to the possibility of regulation on leverage, such as banks (Basel III), hedge funds and private equity (the so-called Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive) and loan-to-value restrictions at national level. Other parts are under discussion at the Financial Stability Board, such as haircuts on securities financing transactions.

The Boundary Problem

But this piecemeal approach intensifies the boundary problem (Goodhart 2008). When regulation for one sector is tightened, businesses will shift beyond the boundary to another sector with a less binding requirement, or to the unregulated sector. That is exactly the point the CEOs made in their statement earlier this week (World Economic Forum 2015). For example, during the run-up to the financial crisis, mortgage loans at the balance sheet of US banks were transformed into residential mortgage-backed securities at special purpose vehicles that were subject to lower regulatory requirements.

In physics, the phenomenon that activities flow to the least constrained segment is known as the law of communicating vessels. The obvious way to get an equal level of fluid in connected vessels is to ‘harmonise’ the pressure across the vessels. The alternative is trying to disconnect the vessels, which is less successful in finance as financial innovation is often able to arbitrage across the segments of the financial system.

Integrated Approach

An integrated rather than entity-based approach to regulate leverage is necessary to stabilise the financial cycle across the financial system as a whole. Regulating leverage would help to prevent misallocation of resources from asset bubbles. The leverage ratio requirement would only be applied to debt-based financing across the financial system. This excludes entities or activities that are fully or largely financed by equity, such as mutual or investment funds. It also excludes entities or activities that are financed by premiums instead of debt, such as insurance companies and pension funds. Leverage ratio requirements would only be applied once debt financing of assets surpasses a certain limit, so that it would only apply to entities and activities that are highly debt financed.

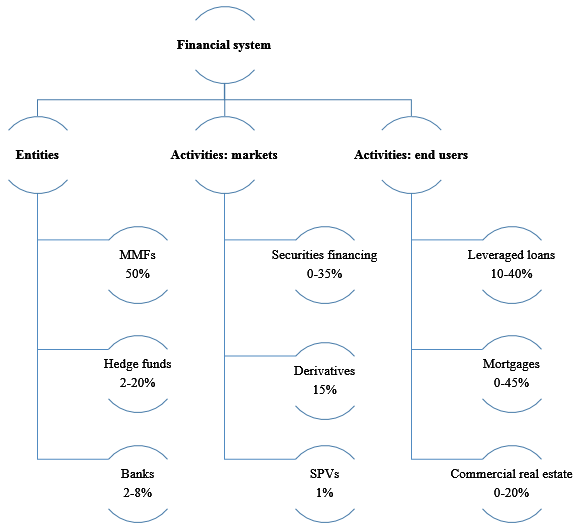

Figure 2. Leverage ratios across the financial system2

Figure 2 summarises the observed leverage ratio in important debt-financed segments of the financial system, when measured as equity divided by total assets.3 Limiting debt financing in one part would provide strong incentives to market participants for increasing return on equity in another part of the financial system. For example, in recent years the lightly regulated market for private equity investments in combination with leveraged loans or leveraged buy-outs has been booming in the context of search for yield.4

Each sector is using its own terminology. Under Basel III, banks are subject to a leverage ratio (defined as equity to total assets). Moving to financial markets, securities financing transactions (such as repos) are typically ‘overcollateralised’ as the value of the underlying assets can vary due to credit or market risk. This excess is called a haircut, and is basically the equity that a party has to provide when entering a securities financing transaction. Housing finance is using its own terminology. A typical indicator used by mortgage providers is the loan-to-value ratio, which is defined as debt to total assets. In Schoenmaker and Wierts (2015), we show that these concepts are related5 and that a maximum loan-to-value ratio of 90% is equivalent to a minimum leverage ratio of 10%.

Microprudential regulation attunes the leverage ratio for each (regulated) segment to the underlying credit and/or market risk of an individual institution or market. This leads to widely differing ratios in practice. By contrast, our proposal is to develop an integrated regulatory approach with a common leverage ratio for debt-based financing across the financial system. This common macro-based leverage ratio would address the migration of highly leveraged activities due to regulatory arbitrage. This macroprudential requirement should override microprudential requirements, as the former internalises the endogenous effects of leverage.

No Silver Bullet

There is no silver bullet for making the financial system failure-proof. Our proposal is a contribution to the evolving thinking on the appropriate design of financial regulation. Nevertheless, we fear that the current attempts of expanding regulation beyond the core banking system may lead to a patchwork of regulations, which may overregulate the financial system with limited effectiveness.

References

Adrian, T and H Shin (2010), “Liquidity and Leverage”, Journal of Financial Intermediation, 19: 418-437.

Almeida, H, M Campello, and C Liu (2006), “The Financial Accelerator: Evidence from International Housing Markets”, Review of Finance 10: 321-352.

Brunnermeier, M and L Pedersen (2009), “Market Liquidity and Funding Liquidity”, Review of Financial Studies 22: 2201-2238.

Gersbach, H and J-Ch Rochet (2014), “Capital regulation and credit fluctuations” in D Schoenmaker (ed.), Macroprudentialism, VoxEU eBook, London: CEPR, 89-95.

Goodhart, C (2008), “The Boundary Problem in Financial Regulation”, National Institute Economic Review, 206: 48–55.

Gorton, G and A Metrick (2012), “Securitized Banking and the Run on Repo”, Journal of Financial Economics, 104: 425-451.

Schoenmaker, D and P Wierts (2015), “Regulating the Financial Cycle: An Integrated Approach with a Leverage Ratio”, Duisenberg school of finance – Tinbergen Institute Discussion Papers No. TI 15-057 / DSF 93.

World Economic Forum (2015), “The Role of Financial Services in Society: Statement in support of macroprudential policies”, May, Geneva.

Footnotes

1 Assumed price growth is 2.5%. The feedback effect on the balance sheet is assumed to be 0.1 for each simulated leverage: .

2 The numbers are indicative and reflect the observed leverage ratios (defined as equity divided by total assets) for each segment of the financial system. The appendix in Schoenmaker and Wierts (2015) details the data sources.

3 The concepts of leverage (L = debt to equity) in figure 1 and leverage ratio (LR = equity to total assets) in figure 2 are linked: L=1⁄LR-1.

4 Under the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive, debt exposure contained in a financial structure controlled by a private equity party is included in the calculation of leverage. In Figure 2, these debts are listed under leveraged loans.

5 LR=Haircut=1-LTV.

Aren’t there actually two very important and rather straight forward silver bullets here? They are called prosecuting the fraudsters and taxing the rich.

This appears to be yet another post from a Western academic conspicuously lacking words like crime, bailout, and fraud.

Sure, makes sense. I say let’s do it. Then we won’t have to listen to our Officialdum tell us they can’t really figure out if we have bubble prices or not. (like Wizard Greenspan was fond of saying) With this approach, you don’t even need to look at prices – just leverage. If no one is spending their own money to drive the prices to where they are, is that really a market price anyway??? I think maybe not.

Interesting input from banking CEOs. A call for regulators to level the playing field. It does seem kinda weird that if you want to limit the risk of leverage in your firm (probably sacrificing some profit for a period of time) and you have competitors to worry about, but the regulators are telling your competitors they have a choice between traditional regulation – or they can choose the newfangled “off balance sheet” or “special purpose vehicle” kind of regulation. Seems like a really good idea – and regulators would have less accounting stuff to learn. A twofer!!!

And it’s only Monday. Probably lots more ideas we could think of before the end of the week. Besides, now that the world’s central banks have bought all the low risk assets in the world, using tons of leverage to juice up some gains out of high_risk_low_return “investments” is probably more prevalent than ever!

I agree that uniform regulation will help prevent excessive credit leveraging during boom periods in our economy. As the author points out there is “no silver bullet to prevent asset price bubbles and financial crisis.

There is another way which would help reduce excessive credit leveraging during excessive asset price increases. With uniform regulation we should enact the 2% Appreciation/Inflation Taxation Policy. This taxation reform policy would automatically change the tax rate on savings and debt investments and change the deductibility of interest paid on debt based on asset price appreciation.

For more information on this tax reform policy please go to wp.me/p42WQA-1E http://www.taxpolicyusa.wordpress.com

The Skyscraper

Outside,

We see only ourselves,

in a mirror,

built for the purpose.

Inside,

We see only assumptions,

a reflection of ourselves,

broadcast for the purpose.

Hedging,

against a certain future,

more death in the hands of fewer,

scapegoats looking for a scapegoat.

Children,

with no representation but parents,

so the parents must go,

attention deficit disorder for all.

New World Order,

always the same as the old,

build until we can’t,

and blame the kids.

Abortion, War and Rapture,

something for everyone,

tune in next week,

for more of the same.

All hope, and no faith,

bridges built to nowhere,

politicians at every corner,

arguing to replace politicians.

Funny,

“for I am resolved to know nothing,”

to follow my children,

turning empire on its head.

Privileged, to be the bad guy,

The 1%,

neither competing nor hiding,

but depending upon Nature,

for wind in a sail.

Exploring the universe,

dots and dashes,

across a fulcrum of fulcrums,

depending on another to open the door.

The aliens pass,

but do not stop,

for a race of preemptive attack,

always an ill-perceived opponent.

Burning their own economy,

watching from a tower,

across the river,

expecting a different result.

I agree that uniform regulations on equity is a good idea to stabilize our credit system. As the author points out “there is no silver bullet to help prevent asset bubbles and financial crisis. Along with with uniform equity regulation we should enact the 2% Appreciation/Inflation Taxation Policy. This reform tax policy would automatically change the tax rate on savings and debt investment and at the same time the interest deduction would be reduced based on an index of asset price appreciation.

For more information on the Policy please go to http://www.taxpolicyusa.wordpress.com or wp.me/p42WQA-1E for the article “American Dream: Restoring Opportunity For All” and video.

The premise that financial borders are leaky and so it’s hard to regulate leverage finance is hard to argue, as is the necessity for some counter-cyclical regulation on bubbles with credit done carefully and a little preemptively. But look what happened in 2008. The credit crunch crashed the world. Not good. We had to spend many more trillions on life boats. On the one hand it is obvious that there needs to be sort of an over-riding law of leverage that all economix adheres to. On the other hand each sector is different. And when it comes to something that is the very backbone of the economy – housing – and they just stop credit cold and raise interest rates like King Alan the Hapless, well that was bad. Then too consider the Saudis. This falls under the natural law of leverage control. They said no, they were not doing a price war – their war was against credit. The real deal. But somehow the frackers aren’t dead yet – like the Monty Python skit about the plague. If each industry had it’s own credit association, like a mutual association, and so the borders between the varieties of leverage financing were impenetrable – then appropriate counter-cyclical finance might work without causing more harm than good. Even Keynes said we should not squander the good years, but should save up for the next rainy day.

Wouldn’t the two more obvious solutions to all this be most importantly stop using tax policy to advantage, nee encourage, debt by ending its deductibility. This is a huge subsidy and produces massive distortion and shifting of risks. [Of course, we should stop using tax policy to advantage capital over labor.]

And, we have to stop protecting creditors whenever something bad happens, to the expense or detriment of all other classes in our society. This results in the cost of debt being too low.

Excellent CYA piece:

… “In an unusual call for regulation, CEOs of major financial institutions urged action on the asset bubble fear earlier this week (World Economic Forum 2015). They ask for a concerted macroprudential approach that addresses potential asset bubbles fueled by current low interest rates. Without such a concerted approach, finance just moves to the least regulated segments of the financial system.”

Although it never hurts to make them, the salient points of this article relating to systemic risks have all been made many times before over a period that now spans decades. So what is this really all about?… IMO somebody’s getting nervous, and it’s not just about the FEAR of asset bubbles, but the reality. A few years late, of course, after their latest slo-mo “financial assetzzz” price bubble is nearly fully formed.

(By the way, who invented the term “macroprudential” and what does it mean?… really. Ditto “shadow banks”.)

In any event, insurance companies, pension funds, and even money market funds, remain vulnerable IMO; whether the debt is in the leveraged entities who are obligated under the negotiable instruments and securities they have purchased, or the securities themselves have been leveraged in an effort to juice returns. And then there are the issues of potential derivatives exposures (que up the AIG song) and annuities obligations following seven years of ZIRP.

Just my views as an ordinary citizen who h/b around for a while and witnessed a little.

IMO the authors’ view requiring that a relatively low “macroprudential” leverage requirement trump higher “microprudential” capital requirements and more intensive regulation of various segments of the financial system is deeply flawed. Various types of financial intermediaries have different roles within the financial and monetary system and require different sets of risk tolerance, not just in terms of debt leverage and capital support, but also liquidity and asset quality. Nor would the measure prevent the formation of asset price bubbles, which are driven in large part by QE-fueled liquidity and ZIRP.

Although systemic concerns are paramount, one size does not fit all. Far from it. This is not to say that systemic risks posed by derivatives exposures, SPVs, hedge funds, etc. should not be addressed and regulated. But despite the attraction of simplicity, I don’t believe a “macroprudential” debt leverage requirement is a satisfactory all-encompassing solution.

So how about we isolate it from the rest of the economy so that if they fail they don’t bring the rest down with them?

Cool idea but politically impossible. It’s too big. Politics likes incremental changes at most.

I would have said a change this big could only happen after a big crisis but after 2008 and the lack of changes I can’t imagine how big a crises it would take to lead to such a big change.

Stock market bubble. Tech bubble. Real estate bubble in a few markets.

Maybe incremental changes with some loose coordination isn’t absolutely impossible.

The embedded table looks odd.

2 and 20 is the hedge fund industry fee structure not leverage ratio. How can 1% be the leverage ratio for SPVs? The numbers all look weird.

How can they be right? The table doesn’t seem to make any sense. Very little written about money, investments, financial markets, economics, phrenology and 1980s-era Japanese VCR clock setting makes sense. Did anybody who was around in the 80s get their VCR clock to stop flashing 12:00? I doubt it. If you tried to read the manual, it just made it worse. Just like finance theory. If you read it, it just gets worse than it seems when you hear about it. You gotta be a financial engineer to really understand the lunacy of finance, but even then you don’t really. Why is it so hard? If you have to ask, you’ll never get it. It’s a rhetorical question

I think the footnotes might explain it. But it’s like when you have to read your digital watch upside down, then flip it around rightside up just to make sure. Which reminds me. My digital watch alarm goes off at midnight no matter what I do to the programming buttons. That’s weird too.

——————————–

2 The numbers are indicative and reflect the observed leverage ratios (defined as equity divided by total assets) for each segment of the financial system. The appendix in Schoenmaker and Wierts (2015) details the data sources.

3 The concepts of leverage (L = debt to equity) in figure 1 and leverage ratio (LR = equity to total assets) in figure 2 are linked: L=1⁄LR-1.

OK maybe 2 and 20 is just a coincidence. that’s 5 to 1 to 50 to 1 leverage, which may be about right. For mortgages and securities financing, it says that there isn’t any equity. That may be honest. Maybe this is just brutal honesty. It reminds me of the Billy Joel song,

If you want pretenderness

It isn’t hard to find

You can have the fraud you need to live

But if you look for truthfulness

You might just as well be blind

It always seems so hard to give

Honesty is such a lonely word

When every number’s so untrue

Honesty is hardly ever heard

And mostly what I need from you

(-from “Honesty” With apologies to Mr. Joel)