Yves here. Earlier this year, we wrote about a past large-scale basic income guarantee program in early industrial England, the Speenhamland system; As much as it was entered into with the best of intentions, to stem rural distress at a time when grain prices shot up by providing for a subsistence-level income, over time it served as a subsidy to employers. As we wrote:

The idea of a basic income guarantee is very popular with readers, more so that the notion of a job guarantee. Yet as we have mentioned in passing, this very sort of program was put in place on a large-scale basis in the past. Initially, it was very popular. However, in the long run it proved to be destructive to the recipients while tremendously beneficial to employers, who used the income support to further lower wages, thus increasing costs to the state and further reducing incentives to work. And when the system was dismantled, it was arguably the working poor, as opposed to the ones who had quit working altogether, who were hurt the most.

This post from VoxEU discusses how efforts to reform social welfare programs in England that operated on the assumption that lack of consistent work (as in periods of unemployment) and overly large families were the big drivers of poverty. But the author describes how the majority of poor now are working poor, and as in the Speenhamland days, social welfare programs are helping to subsidize below-living-wage pay levels. It’s not hard to see how similar factors are in play for US employers like Wal-Mart and McDonalds.

By Jim Tomlinson, Professor of Economic and Social History, University of Glasgow. Originally published at VoxEU

In Britain today, a majority of those in poverty live in working, rather than non-working, households. This challenges the long-held notion that paid work offers a route out of poverty. This column argues that structural changes in the labour market have brought about profound changes in the social security system. A failure to acknowledge these underlying changes means that dialogues about the political direction of the British economy can be problematic and potentially misleading.

n the run-up to the recent general election, 65 Social Policy professors wrote to the Guardian in the following terms:

Now the majority of children and working-age adults in poverty live in working, not workless, households. In other words – and ironically in view of the coalition’s rhetoric – many of those forced to claim the working-age benefits targeted for further cuts are not what the prime minister calls “shirkers” but, in fact, “hard working families” (5th May).

Plainly, the authors were concerned to make an immediate political point about the government’s austerity policies. But the sentences cited above, I suggest, indicate a profound, long-term shift in the social security system and beneath that, a shift of the British economy.

To indicate the significance of this shift we need to go back to two key moments in Britain’s modern history. First is 1795, when the Speenhamland system was introduced in a parish of that name near Newbury in the South of England. Under this system, wages deemed to be below those sufficient for subsistence were subsidised through the Poor Law out of taxes (local poor rates). This system was not actually new, nor did it become universal, but it has been widely recognised as symbolising the rejection of a crucial principle of liberal political economy (Polanyi 1947). The principle is that wages should be determined in a market, and should not be subsidised out of the public purse. Hostility to Speenhamland was widespread amongst the governing class of the time and especially amongst political economists, who argued that such a system created no incentives for the workers to maximise their wages, nor for employers to pay what was affordable to them. These perverse consequences were held-up as the typical result of well-intentioned but misguided intervention in the labour market. Eventually, at another key moment, under the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, such subsidies were outlawed, and liberal political economy emerged triumphant.

Another component of this political economy was the assumption that wages would not need to be subsidised to provide adequate wages; that waged work would be an effective route out of poverty. Of course, this principle was breached at the margins by such mechanisms as Wages Boards (later Councils) which imposed minimum pay on certain sectors of the economy. But here, of course, there was no state subsidy; the state just insisted that employers pay the minimum wage.

The classic mid-20th century Beveridge analysis of the sources of poverty suggested the problem lay fundamentally in ‘interruption to earnings’ (by unemployment, sickness, or age) along with large numbers of children, the latter to be addressed by ‘Family Allowances’ (Cutler et al 1987). While this analysis always misrepresented the labour market, not least in its barely-qualified notion of the ‘male-breadwinner household’, its fundamental idea that normally paid work would provide a route out of poverty has underpinned most modern understandings of how society works down to the present day.

But as the social policy professors’ letter indicates, we have come a long way from a Beveridgean world. My argument is that structural changes in the labour market have brought about profound changes in the social security system. What has changed in the period of de-industrialisation has been the numbers earning poverty wages, and being supported by in-work benefits. Effectively we have moved towards a huge ‘new Speenhamland’ system of ‘outdoor relief’ of the employed; or, viewed differently, large subsidies to employers, which has mitigated, but not cured the problem of poverty-level wages (Farnsworth 2012).

De-Industrialisation

The point that Britain de-industrialised in the second half of the 20th century does not need to be laboured, though it is worth stressing that the process has been long drawn out, beginning in the 1950s (Feinstein 1999).[1]

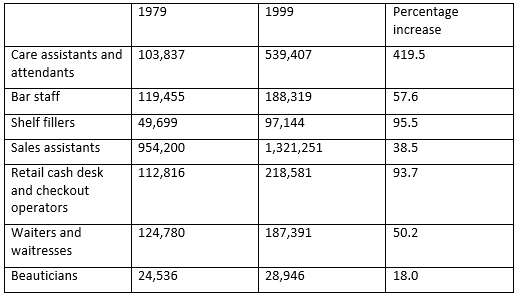

Its effects have been to polarise the labour market. While for those with high levels of formal education the transition to a service economy has provided many opportunities, there has been a proliferation of low-paid work in parallel – “wage inequality is significantly higher now than it was some thirty years ago. This is true for men and women, and is the case in both the upper and lower halves of the distribution.” [NdS1] Machin calculates the ratio between 90th and 10th percentiles for the period 1970 to 2009, and suggests that in the last forty years of that period this dispersion rose by approximately 50% (Machin 2011). This pattern is well summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1. Growth of low skill occupations, 1979-1999

Source: Goos and Manning (2007: 124-5).

While this proliferation of low paid work has been taking place, the ruling ideology has decreed the need to incentivise people into work by maximising the gap between unemployment pay and wages. So reductions in unemployment pay have been accompanied, since the 1970s, by increasing in-work benefits. This began with the Family Income Supplement in 1971, but greatly expanded with the working Families Tax Credit and Working Families Tax Credit in the 1980s and 1990s. Expenditure per claimant on such benefits has increased from approximately £500 in 1970 to £4,300 in 2000 (Blundell and Hoynes 2004). In work incomes are also supplemented by housing benefit payments, most of which now goes to the employed.

While in the industrial period employment did not guarantee an above-poverty income, most poverty was amongst non-workers (the sick and disabled, pensioners, single mothers), or those with unusually large families. Abel-Smith and Townsend showed that in 1960 about 40% of households in poverty (those below 140% of the then National Assistance level) had a working member. But overwhelmingly they also had a large number (four or more) children (Abel-Smith and Townsend 1963). Recent work suggests that a majority of the poor are now members of households with at least one member in work: “As pensioner poverty is now at low levels, the rate of in-work poverty is the most distinctive characteristic of poverty today”. (Joseph Rowntree trust 2012). A different calculation suggests that whereas in the 1970s 3-4% of employed households were in poverty, the figure by 2000/1 was 14%. Between 1975 and the mid-1990s, the incidence of low pay for men in the labour market has doubled (Stewart 1999).

This suggests is that, along with a national minimum wage, wage subsidies have reduced but not prevented poverty amongst the employed. The likely cuts in such benefits under the Conservative government will further reduce their poverty-reducing impact. But whatever the short-run policy on these benefits, it is inconceivable that they will be abolished. So ‘new Speenhamland’ is here to stay.

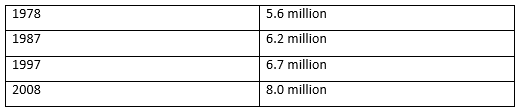

When Polanyi wrote his ground-breaking book on the ‘Great Transformation’ to a market economy he devoted a whole chapter to Speenhamland because he saw the freeing of the market for labour as central to the whole process. As he himself recognised, a completely ‘free’ labour market is an impossibility. But there is no doubt that the degree of freedom in this area is a key marker of the overall nature of the reigning political economy. The paradox here is evident. We are constantly told (by both supporters and opponents) that we live in an increasingly neo-liberal economy, yet the role of the state in the labour market has in many ways increased over the last 40 years. In addition to the ‘new Speenhamland’, researchers at CRESC in Manchester have shown how publicly-financed employment mushroomed from the 1970s (the numbers are significantly higher than the official ONS data because the latter include only jobs within employing bodies ‘controlled’ by the state, and so exclude jobs out-sourced or otherwise funded indirectly).

Table 2. State and ‘para-state’ employment in the UK, 1978-2008

Source: Froud et al (2011: 18).

So if we want to understand the long-term trajectory of the British economy, talk of the ‘success of neo-liberalism’ and ‘rolling-back the state’ seems at best problematic, and at worst misleading.

See original post for references

Indeed. One must be careful: there is nothing so good that the rich cannot somehow warp it into something that makes them even richer at the expense of making everyone else poorer.

Example: some ‘liberals’ recently lauded the state of California for providing health care to illegal immigrants. But when you think about it, this is really a program of taxing the middle class to subsidize the cheap labor of large agribusinesses (why not force the employers of illegal immigrants to pay for their health care directly? But we can’t say that in public). Certainly many have pointed out that WalMart can only pay such low wages because of all those ‘anti-poverty’ government subsidies…

indeed, including a job guarantee. i do prefer the job’s guarantee over a BIG, but it’s not hard to see how the former can be abused by the elites as well

Democratic control is key, I agree.

At least Thomas Jefferson fed, housed, and clothed his slaves. WalMart and McDonalds can’t seem to be able to afford to do any of that for their rental slaves.

Yes, there really is almost 200 years of history to show worked examples on this subject. Income guarantees have proven to lower living standards.

I couldn’t believe it (actually, I could) when I saw this http://s28.postimg.org/wx2l79bj1/image.jpg (hope you can all see the text from the exhibit, the key text is on the left “… combined with a ‘topping up’ system for the local poor rate forced wages down to starvation levels” at a town museum near me. Yep, there were riots in 1830 despite, or rather because of, the provision of a Basic Income.

All the way back to the 1830s in Europe? And followed by socialist revolutions in the 1840s. So it all leads me to believe that capitalism was dysfunctional from the get go. Right after it fledged from feudalism and because it was still a feudalist bird. It was never meant to function for everyone. In terms of the 20th C. the UK was philosophically ahead of us as usual. I think because there were contradictions that we couldn’t avoid. I’m no economist, nor philosopher, but I’ve always thought that our national planners looked at least 50 years into the future and acted accordingly. So that when we followed the British lead and dismantled our economy by supply side economix in the 80s and until now, we were following a template for some form of survival for the rich first and the rest of us second. Because we all can’t suck up all that profit – that would make it necessary to move to Jupiter and colonize like there was no tomorrow …the earthly system controls who wins, not the contestants. So why pretend it’s all freedom and equality? That fiction has become extremely offensive.

“broken from the get go” (or, to use the economese word, “equilibrium” is a myth). One of these days I’m going to excerpt a book that shows the transition from feudalism to capitalism through the lens of the witchburnings.

Don’t forget the moldy rye bread finger buns sprinkled with stimulants!

Skippy…. sure to crack the ice and any gathering and get the party shifted into high gear…. pun-ho-rific

Actually, the biology/botany beneath those stories is part of it.

It was enjoyable unpacking that stuff back in the day on NC, Salem, quaint French towns, the book of Revelations, leaded petrol, et al.

Skippy… now were stuck unpacking blow by blow events as they unfold with decreasing space between event horizons, without even a modicum of time to catch our breath or pause for deeper introspection.

PS. in awe of the steady hands at the helm tho….

Isn’t that book Silvia Federici’s *Caliban and the Witch*? http://www.akpress.org/calibanandthewitch.html

However, in the long run it proved to be destructive to the recipients while tremendously beneficial to employers, who used the income support to further lower wages,

Ideally, shouldn’t work be voluntary?

thus increasing costs to the state

Irrelevant to a monetary sovereign? Especially if implicit welfare for the rich, such as a government-privileged banking system is eliminated? In the interest of precluding price inflation?

and further reducing incentives to work. Yves Smith

You mean further reducing incentives to have a job. People can and do work without jobs and if they have resources, such as the common land they formerly enjoyed, they can do so productively. The population SHOULD have the genuine option to refuse to work for someone else. Why on Earth not? Or should wage slavery be the norm for all but a few? Then employers will have to make the jobs they offer sufficiently attractive that people will desire to work for them – such as sharing profits with the employees. We can give the population that option via a generous BIG.

Jobs in the US should have been in the form of co-opts but explicit and implicit subsidies for the banks precluded that, I’d bet.

Thanks for making this point, which can’t be stressed enough. The whole “work or starve” and hell take the hindmost thing is made easier by the fact that propaganda works on at least half the population who kiss the whip with gusto because Jeebis.

Not because of Jesus but in spite of. A Baptist group, for example, agreed not long ago that payday lenders should not charge more than 36% interest. But that’s three times what Nehemiah 5:11 condemns (1% per month = 12% per year)! Even Calvin thought interest should be limited to 5% and that the destitute* shouldn’t be charged any interest at all.

*Exodus 22:25 may simply mean the poor, not those who are destitute.

Well said John. I’m curious to see if anyone disagrees with you and Jamie.

Ideally, yes. Human labor should be a gift. Humans should not be rented (as wage labor) or sold (as slavery). How to get to that point….

How indeed.

Well, John says use a BIG. I say use universal unemployment insurance. Both ideas have the commonality of ending the monopoly of employment on income. They do this not by having politicians allocate projects, but instead, sending currency units directly to citizens to spend as each individual sees best.

I mean this seriously, it would be interesting to have succinct plans – as in proposals with concrete details – that you, Firestone, Alt, Wray, and others advocate written up for reference. The operational how is exactly where there appears most opportunity for discussion.

I’d say most of the problems that Wray claims a JG would solve are better addressed through direct regulation and direct cash payments. Want to make life less crappy for the most marginalized and voiceless members of society? Well, how about ending the drug war and implementing some form of universal health insurance? That would result in less spending, not more. Want to increase the number of jobs? Prosecute fraudsters and reduce the workweek. Want to address inequality? Stop doing the policies that exacerbate it, from tax cuts for the rich to warmongering to bailouts.

It doesn’t follow that a “basic income guarantee” is a bad idea just because a partial subsidy failed. If by “basic income guarantee” one means a decent standard of living, you can’t reasonably compare that to a small stipend that doesn’t actually relieve people from the necessity to work for a living. And yes, a lot of pointless economic activity would cease if people were guaranteed a decent standard of living… and a lot of capital accumulation wouldn’t take place. I.e., a lot of people couldn’t “get rich” off the needs of the lower classes without actually producing something worth producing. I don’t see that as a bad thing.

I think the article makes a good point. Reminds me in some ways of comments by some in the mainstream world that slaves didn’t have it so bad.

I favor a job guarantee over a guaranteed basic income. However:

Aren’t there some cultural differences that may be important when comparing a basic income today to Speenhamland? Weren’t the vast majority of the unemployed in Speenhamland those without any experience of having a job like we have today? As peasant farmers they may have owed part of their crops to the landlord, but they did not have a boss looking over their shoulder, nor were they in danger of being fired, nor did they depend upon a job for their livelihood. Also, as far as employers were concerned, they were not consumers such as we have today. Didn’t Adam Smith point out that the peasant did not have to buy shoes, but cut easily make them for himself? If you have never experienced having a boss with the power to take away your livelihood, and you have a guaranteed income, why would you look for a job?

The unemployed were not peasant farmers, by definition. Peasant farmers had work, they had a living. The unemployed were those who did not have land of their own, or family to take them in. Peasant land was confiscated with enclosures and evictions to profit the “landowners” to enrich the elites and force the peasants into accepting paid labor (at below subsistence level wages).

Pardon me. I should have said that they “had been” peasant farmers.

It would seem that the only thing that will help labor is organization. Strikes and demands from the bottom for better benefits and wages would historically be the only way proven to work.

Hi Larry, I must apologize for a reply to a good comment of yours in which I defended radio shack, in the future I will try, when I have a ridiculous idea like that one, to put it in the form of comment rather than reply…To the point here, I agree that organization would be effective, and I think the elite think so as well considering the murders of trade unionists since the passage of CAFTA

I think the spirit of Polanyi’s work is that he didn’t want labor to be treated as a commodity. I think this would imply a basic social safety net.

I would see the next step up as being a job guarantee program at a living wage paid for by the sovereign to do useful work as defined by communities.

The next step would be for employers to offer better wages to attract these workers for private employment. This would help reduce inequality and the power that capital has over labor.

Great comment! It is not some sort of immutable law of physics that employers will always pay starvation wages.. If we seize the political power we need, to radically transform our political economy, it won’t prove very difficult to ensure everyone can afford to live in dignity, without having to beg for scraps from kleptocrats!

The key transformation is a cultural one. If we establish a living wage as a moral value, then trying to pay less than a living wage will be unthinkable in decent society– like murder.

In the meantime, as Larry points out above, the most effective method for labor to improve its lot is through organization into unions (or worker-owned businesses, etc.).

You can’t legislate morality. Nuremburg Tribunals anyone!

The state should be the employer of first resort… paying a living wage. This would set the bar for any for profit businesses. Any number of services could be (and have been at times) socialized and staffed with civil servants. This is, in large, measure what the new trade deals are about… The end of nationalized services and industries.

I avoid “social safety net” and prefer the term “social insurance” because the “safety net” (dead) metaphor turns on one person walking a tightrope. That’s not the kind of society or world I want to live in.

Well said, those are the basic logistical questions to flesh out.

1) What is a living wage? (including who is entitled to it)

2) What is the community?

3) How does the community go about defining useful work?

4) How does the community communicate its definition of useful work?

5) How does the community implement its definition of useful work?

It would be very interesting to have guest authors advocating specific plans where concrete details were explored. The lack of consensus on the details is one of the reasons I’m rather hesitant of JG over direct cash payments. Mosler advocated an $8/hr wage. Tcherneva thinks that social entrepreneurship by nonprofits can do this. Those kinds of proposals strike me as incredibly naive of how our present system actually operates.

How about starting by making a list of things that should not be produced for profit.

1. Healthcare

2. Energy Resources

3. Basic Food Production

4. Technical Research

5. Communications

6. Public Transportation

7. Education

8. Public Service Professions ie. Police, Fire, Military, Government

9. Basic Housing

10. Public Banking

11. Public Insurance

This list would comprise essential goods and services that everyone in society needs to live a decent life. Fair wages can be set for anyone wishing to enter the jobs needed to supply these goods and services.

Democratically elected officials would set public policy.

Everything else and be left for profit driven activities.

This idea that everything in the world must be done for profit will be the death of us all.

That is a very interesting frame indeed. I like the way it proceeds from first principles.

Exactly. First principles. The trouble I see today is that as a society we can’t agree on the basic principles on which our decisions are based. And the principles every citizen understands at a basic level-fair play, freedom, equality, democracy- have been so distorted and subverted by narrow self-interested factions, that they loose their power to motivate and move society as a whole. We are at a stage where we must fight for our principles.

Calling people out on the principles they base their actions on cuts thru the BS very quickly.

Evaluating the results of their actions reveals if they are liars or not.

Building a sharing society will begin to reverse the destruction of a profit society. This seems to be a very powerful fact. It’s not about caring for the casualties of the neoliberal system. It must be about building a resilient system of mutual support.

First place to start is the workplace. Healthy people and families already do this at home.

I very much agree society should ensure every citizen has access to the basics of those things (although how much of each is certainly an area of differing opinions).

But what do you mean by profit? Some of the most wasteful organizations in our society are not for profit organizations, from hospital franchises and research universities to the DEA and NSA.

And I hate to break it to you, but democratically elected politicians do set public policy. What is it about spending more money that will improve their decision making processes?

I think we need to focus less on money and more on propaganda and lies. Describing the current state of government as being infected with tumors and cancerous growths is apt.

You don’t kill the government- democracy- you get rid of the tumors. Because the current state of propaganda is so overwhelming, these changes are extremely difficult.

The principle is reward work and contribution. Restrict or eliminate parasitism.

By profit I mean for those individuals who feel the need to strive to accumulate more than the basics in life, let them knock their socks off. Just make sure these accumulators cannot dominate the entire social system. Seems pretty basic.

Propaganda, fear, violence. Work on these and we can move forward.

I guess it all depends on if you view humanity as fundamentally good or evil. If you believe in the good- your public policy will follow a certain path. If you believe in the evil nature of humankind you get another. We have allowed the evil view the upper hand.

Well said. Less focus on money, more on the cancerous growth of tumors infecting all levels of government in our society.

The issue is not that government is too small. The issue is that parts of the government are hazardous to public health.

Is a job about 1800 hours a year as in the U.S., or about 1400 hours a year as in the Netherlands, or somewhere in between? I don’t know whether this gets too specific too fast, but it seems to me one of the basic logistical questions.

Exactly, the number of hours to be worked is a great example of a concrete detail that is central to any specific plan.

I’d observe that the US would benefit enormously from reducing the work week and implementing a standard set of mandatory paid holidays and vacation days. The interesting thing is that can be done operationally without needing to create a JG program. We already have a legislative framework for that kind of direct labor market regulation. (If you’re unfamiliar, it’s called FLSA – the Fair Labor Standards Act).

“But the author describes how the majority of poor now are working poor, and as in the Speenhamland days, social welfare programs are helping to subsidize below-living-wage pay levels. It’s not hard to see how similar factors are in play for US employers like Wal-Mart and McDonalds. ”

Yes.

From a 2014 Rolling Stone article:

“Taxpayer subsidies to the working poor make welfare queens of some of the world’s most profitable corporations. “The large restaurant chains, the Walmarts – they hold themselves up as captains of the free-enterprise system,” Rep. Miller says, “but their whole business plan is dependent on using the social safety net.

“One of the most expensive programs that taxpayers fund is the Earned Income Tax Credit – which doles out $60 billion in welfare payments to poor working parents every year at tax time. The EITC lifts millions out of poverty. But thanks to the inadequacy of the minimum wage, it also creates a perverse incentive. The EITC subsidizes poverty-wage work, so businesses can – and do – drive wages even further below the poverty line.

“More than one-third of the EITC is pocketed by employers through artificially low labor costs, according to a Princeton economic analysis. Worse: The EITC actually hurts many single workers without kids, who don’t qualify for the subsidy and are made strictly worse off by its existence.

“A rising minimum wage is a tide that lifts all ships….”

http://www.rollingstone.com/politics/news/hey-washington-the-pay-is-too-damn-low-the-minimum-wage-war-20140227

Counts of people in various roles don’t appear to be adjusted for general population growth? That seems like an oversight when comparing periods thirty years apart.

The principle that all income for ordinary people must flow through jobs underlies a lot of our worst social policies. It promotes the concentration of money and thus power in the hands of “job creators”. It justifies providing financial incentives to corporations to locate in the jurisdiction. Since states and local governments are not sovereign in their own currency, the incentives starve jurisdictions’ ability to pay for education, health centers, adequate civil services from safety inspections onward.

The arguments I’ve seen for a job guarantee seem to me to badly underestimate the administrative complexities, the likelihood of continued inequality, and the ability to agree on how much is optimal economic growth and exploitation of resources and labor. But then maybe I’m just unreasonably cynical about the cooperative flowering that would emerge (or maybe I’ve spent too much time in blog comment sections to be able to envision the unanimous generosity of spirit that would make it work). In terms of political possibility, it seems to me that building on a popular universal income program like Social Security has a more realistic chance of success than any good jobs program that I can imagine.

It also incentivizes the making of Moar Stuff, of which we already have way too much. Bottomline: people need air, water, food, clothing, shelter, the society of their fellow creatures, the arts and that sort of thing. We do not need Moar Stuff.

It is Groaf that requires jobs. And, of course, produces Moar Stuff.

This is really interesting. No one has offered a dissent, either of the principle in your first paragraph or the operational challenges in your second. Or of what John laid out. Or Jamie. Or Rosario. Or HotFlash.

Yves clearly set this post up as an opportunity for those advocating MMT ideas to exchange ideas with readers who have different opinions.

But these comments are standing as is. Where did the JG advocates go? I don’t mean that in a taunting sense. I mean it as in an observation of the changing vibe of the undercurrent of discussion all across our society. Maybe we really are making inroads that traditional growth just isn’t a solution anymore. Obviously one data point in a holiday week with China stocks crashing and the Greek referendum doesn’t a trend make, but I’m curious what interaction happens on the next few posts about BIG and JG and so forth.

I have always been puzzled by the term “de-industrialized” as if that ever really happened. The relationship of labor (including non-industry labor) to industry has and always will exist whether it is tariff/subsidy protected native industry, fully out-sourced, and/or fully automated (as seems to be the current course). Our whole society is fully industrialized and there is not a single branch of the modern economy that is not industry dependent. If anyone can clear up what is meant by the term I would appreciate it.

Tomlinson’s argument on the growth of low-paid work is fundamentally flawed.

Yet that’s exactly what the author is doing, talking up neoliberal canards.

Deindustrialization is not responsible for the proliferation of low-paid work. Inequality is the cause, not the effect. Low paid work is necessitated by high paid work. It’s basic math. That’s how percentages work. In order for connected insiders to enjoy outsized gains, less is left for those on the outside. This is exactly what has happened. It’s not that low wage workers are earning less; rather, high wage workers are earning more.

And the notion of low skills and high skills is a complete fiction, not an actual description of the labor force. The whole point of that kind of language is to justify the wage inequality, not explain why it exists. Care assistants and attendants are low skill occupations? Hogwash.

Plus, for US purposes, I’m not sure comparisons with the UK demonstrate what MMTers want it to demonstrate. The NHS is a great example of a program that works quite well even thought it’s funded by taxation and operates independently of work in the formal economy. Wage subsidies, meanwhile, are a great example of a program that doesn’t work well precisely because it’s a public private partnership that depends upon work in the formal economy rather than direct cash payments that offer an alternative to work in the formal economy.

Living wage or job guarantee is useless if one cannot afford housing.

It have to be couple with the bottom two levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs.

From wikipedia, from the bottom up

1. Air, water, and food are metabolic requirements for survival in all animals, including humans. Clothing and shelter provide necessary protection from the elements.

2. Safety and Security needs include:

Personal security

Financial security

Health and well-being

Safety net against accidents/illness and their adverse impacts

And people who have reached the self-actualization peak of Maslow’s hierarchy probably need to become pariahs.

This VoxEU piece is also discussed at Economist’s View:

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2015/07/de-industrialisation-new-speenhamland-and-neo-liberalism.html

If BIG is not supported by inflation or productivity adjusted minimum wage

then it will produce effect as described but only in long term. In short term, BIG is above subsistance level when it was implemented (it was calculated as such) but in time it becomes obsolete due to its initial success.

Good income and benefits raised by implementing the BIG add to a jump in demand and wages making it seem unneccessery in supporting the income. BIG’s success become its demise, since in time, it is forgoten why it was needed in the first place.

To prevent that, BIG has to be supported by inflation or productivity adjusted minimum wage. Idealy, BIG should be implemented only in support of a Job Gurantee and inflation or productivity adjusted minimum wage.

But, there is another mechanism for lowering the income in free market;debt growth. Debt growth can hide stagnating wages from the eyes of workers. Great moderation is the proof of that.

Relying on debt growth to support agregate demand is the source of growing inequality in a Credit scoring system where poor get burdening scores while the rich enjoy lowest interest rates.

All of Pikketty’s work could be summed up describing how Credit scoring system as presently used is the main source of growing inequality.

I am reminded of that other great Englishman, Ronald Englefield, and his book, A Critique Of Pure Verbiage. The whole dreadful affair above might have been stated in a half dozen intelligible sentences.