Yves here. Don’t be deceived by the dry title. This is a very readable and important account of how Europe came to embrace some of the key elements of its current monetary policy and exchange rate straitjacket.

By Ashoka Mody, Professor of Economics at Princeton, and Dae Woong Kang, an undergraduate student and researcher in the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton. Originally published at Bruegel

In 1997, Milton Friedman warned that when politics clashes with economics, the outcome is not a pretty one. This column reviews some of criticisms and weaknesses of the European macroeconomic system, taking a historic look at the decades leading up to the creation of the euro. The clash Friedman warned about is manifest now in Greece. The economic logic for dealing with Greece is clear, but politics continue to defy economics.

Flexible Exchange Rates in the Aftermath of the Great Depression

Up until the Great Depression of the 1930s, the predominant view was that national currencies should be exchanged at fixed rates. The expectation was that the rate would not be changed unless there was a compelling reason to do so. The success of the gold standard between 1870 and 1913 had deepened the faith in fixed rates. During those years, the world’s major economies had maintained a commitment to exchanging their currencies for a fixed amount of gold and, for much of the time, the world economy prospered. But the gold standard proved completely unworkable after 1913, and was, by Barry Eichengreen’s influential account, a major contributor to the severity of the Great Depression (Eichengreen 1992a). Fixed exchange rates, the Harvard economist Gottfried von Haberler later commented, became “a casualty of the Great Depression” (Habeler 1976, p.17).

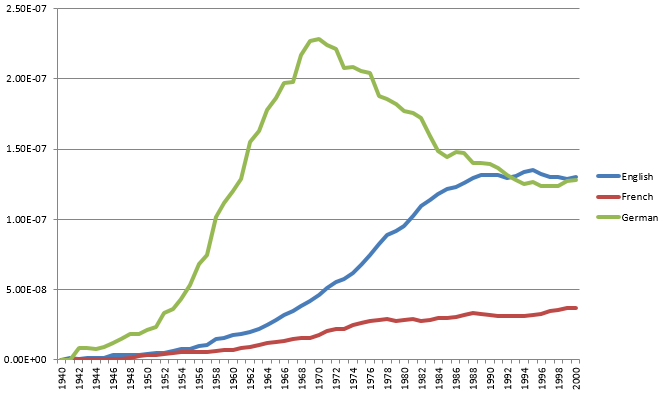

That triggered a revolution in international macroeconomic thinking. In the 1940s, a new phrase, ‘flexible exchange rates’, appeared in intellectual discourse (Figure 1).1 Strikingly, Germans were the pioneers in discussing flexible exchange rates (‘flexible Wechselkurs’ or ‘schwankender Wechselkurs’) while the French showed the least interest (‘taux de change flexible’ or ‘taux de change flottant’).

Figure 1. The usage of the phrase ‘flexible exchange rate’ in German, English, and French books

Note: The graph was created using the Google Books Ngram Viewer (https://books.google.com/ngrams/info). It reports the frequency with which the phrase flexible exchange rate is mentioned in the books scanned by Google; ‘flexible Wechselkurs’ was used for German books and ‘taux de change flexible’ for French books. The English variation ‘floating exchange rate’, the German variation ‘schwankender Wechselkurs’ and the French variation ‘taux de change flottant’ yielded similar trends.

The immediate post-World War II monetary system was fashioned at that intellectual cusp. In July 1944, when policymakers met at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, it was still hard to break free from the fixed exchange rate mind set. But in deference to reality, the new system allowed countries to ‘adjust’ their fixed rates under international supervision. To authorise these changes – and to oversee the world’s exchange rate policies – the IMF was created.

The system was short-lived. With capital criss-crossing the world in ever larger volumes, the fixed rates were continuously tested. In 1953, the University of Chicago economist and later Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman proposed the more widespread use of flexible exchange rates (Friedman 1953). As Figure 1 shows, the usage of the phrase ‘flexible exchange rates’ accelerated, once again in Germany.

Increasingly, however, countries were unable to maintain their commitment to a fixed exchange rate while also achieving their domestic policy objectives. In particular, countries experiencing high inflation rates needed to devalue to compete internationally. But the international community discouraged devaluation because it feared that others would follow by also devaluing to restore their competitiveness; and, domestically, governments faced the political charge of having mismanaged the economy. For this reason, devaluations tended to be delayed. In the meantime, financial markets –foreseeing an eventual devaluation – moved vast sums of money across borders to mount speculative attacks against vulnerable currencies. Such currencies were ultimately devalued despite a mélange of responses that included restrictions on imports, controls on capital movements, restrictions on prices and wages, and severe austerity (Bordo 1993, p.83).

It was only a matter of time. The US – the lynch pin of the Bretton Woods System – was running high inflation rates and could not sustain its commitment to pay $35 for an ounce of gold. On 15 March, 1968, the so-called ‘two-tier’ system was introduced under which central banks would transact only with each other at the $35 price and would no longer buy or sell at the market price. At that point, the monetary historian Michael Bordo says, the Bretton Woods system effectively came to an end. Since it had become fully operational only in December 1958, it had lasted for just under a decade (see Bordo 1993 for a more detailed account).

In a March 1969 paper, Harry Johnson – of the London School of Economics and the University of Chicago – restated Friedman’s argument. Greater exchange rate flexibility would allow national authorities greater freedom in domestic macroeconomic management. In contrast, he said, “little reasoned defence of [the fixed exchange rate system] has been produced beyond the fact that it exists and functions after a fashion, and the contention that any change would be for the worse” (Johnson 1969, pp. 12-13).

On 29 September 1969, Germany let its exchange rate float. Once again, the Germans were ahead of the Anglo-Saxons.

Initiating a European Monetary Union

And then Europe chose to go against the tide of history. The French steered Europe to its preference for fixed rates and the Germans, reluctantly at first, followed. In August 1969, the newly elected French President Georges Pompidou quickly devalued the French franc and made monetary union of Europe one of his priorities. Willy Brandt, who became West German Chancellor in October, was willing to test the idea so that he could gain space for reconciliation with the East, Ostpolitik. Thus Brandt agreed to Pompidou’s call for a summit of European leaders at The Hague in December 1969 to discuss, among other things, a European monetary union. The leaders created a committee headed by Pierre Werner, the Luxembourg Prime Minister, and in October 1970, the Werner Committee delivered its blueprint.

The Germans were not yet ready to concede. At the Franco-German consultations in July 1971, they reported on “the advantages [floating the D-Mark] had already brought” (Rutherford 1973). In October 1971, at the Annual Meetings of the World Bank and the IMF, German Economics Minister Karl Schiller stated, “the mechanism of exchange rate adjustment has been far too rigid… it is important that unrealistic parities [exchange rates] should be adjusted promptly and sufficiently. We ought to look at parity changes not as matters of political prestige and of victory and defeat but from a sober economic point of view” (Schiller 1971, p.195).

The Franco-German differences on exchange rates reflected a deeper difference in their view of the role of markets in determining economic outcomes. Their positions were starkly different even when negotiating the Treaty of Rome in the 1950s to open borders to European trade. The then German Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard opposed the Treaty because he wanted borders to be open for all countries, not just to other European countries. The French did not want to open borders, even to other European countries (Marjolin 1989, p.281).

But, as Figure 1 shows, in the early 1970s the German curve began to bend towards the French one. Not wanting to be seen as setting back the European integration process, the Germans fell in with the French. In 1972, following a recommendation of the Werner Report, the so-called ‘snake in the tunnel’ system was created as an effort to limit the bilateral exchange rates of major European economies. That arrangement was quickly swept away by the global turmoil of those years. In 1979, the exchange rate mechanism was an effort to revive the snake. Once again, countries were required to maintain their bilateral exchange rates within narrowly defined bands. It eventually went up in flames in 1992-93.

Despite repeated reality tests, successive French presidents continued to push for fixed exchange rates within a monetary union. For them, the dependence on German monetary policy was intolerable. The concern was most passionately stated by President Francois Mitterrand in a September 1989 conversation with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher: “Without a common currency, we are all, us and you, already at the will of the Germans. When they raise their interest rates, we are obliged to follow them, and you who are not even in the monetary system, you do the same thing! Thus, the only way to have a right to have a say, is to establish a European Central Bank where we can decide on things together,” Guigou (2000, pp. 76).

Notice that although the German intellectual discussion of flexible exchange rates declined after around 1970, it fell only to the Anglo-Saxon level. The French usage remained steadfastly low. Besides deep ideological differences, the Germans were always supremely conscious that a monetary union may force them to pay the bills of other nations that were unable to withstand the rigours of such a union. For this reason, the German public and the technocrats opposed the single currency. But one man pushed ahead: German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. From the summit of European leaders at Strasbourg in December 1989 (when he gave the go ahead to start drafting the Maastricht Treaty) to the summit at Brussels in May 1998 (when he insisted that Italy would be among the first members of the euro club), he shepherded the euro to its birth. In the process, he legitimised a new groupthink.

Critics of the Common Currency

Roland Benabou says that groupthink has four characteristics: a leader to champion a view; the disregard of external critics; the silencing of internal critics; and, as a consequence, the slide into missions of great – and unreasonable – risk.2

The conscious disregard of external critics is well known. A whole swathe of ‘Anglo-Saxon’ contemporary economists and policymakers warned against the dangers, starting with the University of Cambridge economist Nicholas Kaldor, who wrote a scathing critique a few months after the Werner Report was published.3

Among internal critics, some left and others aligned themselves to Kohl. Among the most prominent critics who chose to leave was Bundesbank President Karl Otto Pohl. Like all German civil servants, he deferred to the goal of European integration. But on the single currency, he was clear that Europe was not ready. And while it was possible to construct a technical vision of how such a currency may eventually operate, much groundwork, he believed, was needed before the conditions for success would be attained. In 1989, in the months before German reunification, Pohl made repeated public efforts to slow the process down. Indeed, on one occasion, he said that British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher – the fiercest political critic of the single currency –understood the risks better than his own chancellor.4 Repeatedly undermined, Pohl left in May 1991 before his term ended.

Finance Minister Theo Waigel, personally at odds with Pohl, agreed with him on the economics. The two had opposed the conversion of one East German Ostmark for one West German D-Mark. Waigel also insisted on a slower pace of European monetary integration at least till the Maastricht Treaty in December 1991. But then he fell in with Kohl’s agenda. The compromise that Waigel shepherded was European fiscal austerity to protect Germans from picking up the tab for others. Once again, contemporary critics warned that this – along with a single monetary policy for disparate countries – would make macroeconomic management harder, especially in economic downturns. But disregarding those warnings, an incomplete monetary union, without the safeguards of labour mobility and a fiscal union, was forged.

Concluding Remarks

Thus, at that bend in history – when politics defied economics – the European macroeconomics of austerity was born, protected by groupthink and necessarily cast in institutional straightjackets. Even as the Europeans narrowed their macroeconomic options, the rest of the world moved steadily to macroeconomic flexibility – in exchange rate, monetary, and fiscal arrangements.

In the run up to the euro in 1997, Milton Friedman warned that when politics clashes with economics, the outcome is not a pretty one. Today, the clash is manifest in Greece. Ironically, although the French intent was to reduce German influence, a more dominant Germany now determines how Europe sees its financial crisis. The economic logic and evidence for dealing with Greece are clear.[5] Politics, however, continues to defy economics and groupthink prevents the painful but sober course.

See orignal post for references