By Stephen Cecchetti, Professor of International Economics at the Brandeis International Business School and Enisse Kharroubi, Senior Economist in the Monetary Policy Division in the Monetary and Economic Department, Bank for International Settlements. Originally published at VoxEU

A booming financial sector means economic growth. Or does it? This column presents new evidence showing that when the financial sector grows more quickly, productivity tends to grow disproportionately slower in industries with either lower asset tangibility or in industries with higher research and development intensity. It turns out that financial booms are not, in general, growth-enhancing.

Finance and growth are intimately connected. For at least two decades, we have known that for economies to thrive, they need deep and broad financial systems (Levine 1997). But what is true for emerging market economies may not be true in the advanced world. That is, finance could very well be a two-edged sword. When credit is relatively low, or the financial sector’s share of employment modest, higher levels of debt add to growth. But there is a threshold beyond which it becomes a drag. There is now considerable evidence that productivity grows more slowly when a country’s government, corporate or household debt exceed 100% of GDP (see Reinhart and Rogoff 2010, Cecchetti et al. 2011, and Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2012).

The Link Between Financial Growth and Real Growth

In a recent paper (Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2015) we broaden the focus to the study of the relationship between financial growth and real growth. Or, more specifically, the effect of changes in the size of the financial system on total factor productivity growth. And, unlike the level relationship – where finance is good for a while – in this case the result is unambiguous. The faster the financial sector grows, the worse it is for total factor productivity growth. Using panel 20 countries over 30 years, we establish that there is a robust, economically meaningful, negative correlation between productivity and financial sector growth. We also find that causality likely runs from financial sector growth to real economic growth.

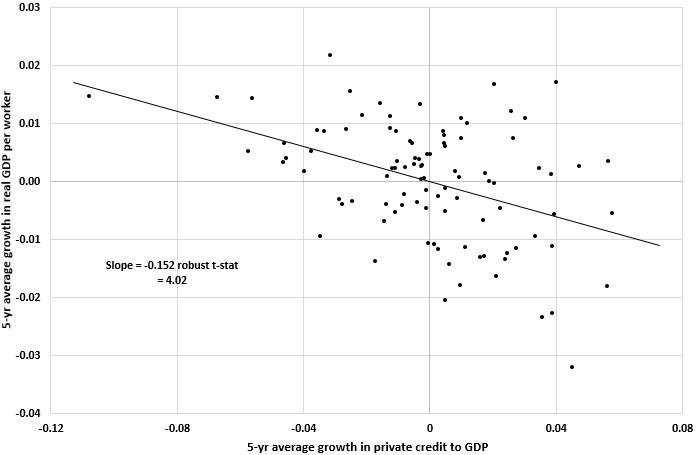

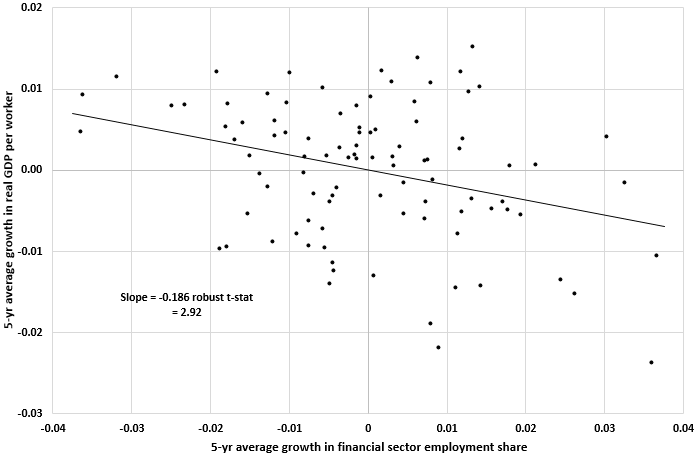

Graph 1 plots growth in real GDP per person employed on the vertical axis against two measures of financial sector growth on the horizontal: growth in private credit to GDP (left-hand panel) and growth in the share of total employment that is in financial intermediation (right-hand). We use data on 20 advanced economies from 1980 to 2010. In every case, data are averaged over five year periods and measured as deviations from the country mean. The figure shows a clear negative relationship between financial sector growth and productivity growth. The line running through the scatter plot has a negative slope with a coefficient that is significantly less than zero at the 1% level in both cases.

To ensure that the impression from the graph is in fact an accurate reflection of the relationship in the data, we estimate a simple growth regression that both examines a variety of measures for financial sector growth and controls for things like initial conditions, inflation, the size of government, trade openness, population growth, investment to GDP and the occurrence of financial crises. Our conclusion is quite robust – there is a clear negative relationship between financial sector growth and real growth.

Graph 1. Financial sector growth and productivity growth

Graphs plot non-overlapping five year averages rates of deviation from country means for Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Spain, Finland, France, the United Kingdom, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden and United States over the period from 1980 to 2010. The right hand panel controls for beginning-of-period real GDP per worker.

We can get a sense of the size of the effect by looking at some specific examples. Consider the cases of Ireland and Spain. Starting with Ireland, from 2005 to 2010 the ratio of Irish private credit to GDP more than doubled, growing 16.9% per year. By contrast, over the five years from 1995 to 2000, it grew at a more modest average annual rate of 7.7%. Our estimates (not reported here) imply that this 9.2 percentage point difference has resulted in a productivity slow-down over 2005-2010 of 0.8 percentage points per year compared to the period 1995-2000. This accounts for around 30% of the 2.9 percentage point drop in productivity growth (from 3.3% a.r. to 0.4% a.r.) that occurred over this period.

Turning to Spain, from 1990 to 1995, credit to GDP was almost constant (-0.22% per year) while Spanish productivity was growing 1.7% per year. Fifteen years later, from 2005 to 2010, credit to GDP grew 8.1% a year but productivity grew only 1% a year. Our estimates suggest that, if credit to GDP had been constant instead of rising by 8.1 percentage points, then productivity growth in Spain over 2005-2010 would have the same as it was in 1990-1995 (1.7% per year).

Why Finance is Doing Harm

What is behind this empirical regularity? What is the mechanism by which finance, something we know to be fundamental to the operation of the economy, is doing harm? Our hypothesis is that it arises because finance tends to favour relatively low productivity industries as such industries usually own assets that are relatively easy to pledge as collateral. So as finance grows, the sectoral composition of the economy changes in a way that drives aggregate total factor productivity down. The intuition for this comes from the observation that it is easier to obtain external finance for projects that are based either use tangible capital in their production or produce more tangible outputs. The more tangible a firm’s assets or output, the easier it is to pledge them as collateral for a loan.

We take this prediction to the data and study 33 manufacturing industries in 15 advanced economies. The key to figuring out which sectors are most likely to be damaged from financial sector growth requires that we look for the sectors where pledging of either assets or output is difficult. On the asset side, we can measure this directly from information on asset tangibility. For output, we use research and development intensity as a proxy.

Our results are unambiguous. When the financial sector grows more quickly, productivity tends to grow disproportionately slower in industries with lower asset tangibility, or in industries with higher research and development intensity.

As for the quantitative implications of these estimates, we find that productivity of an industry with high asset tangibility located in a country experiencing a financial boom tends to grow 2.5-3% a year more quickly than an industry with low asset tangibility located in a country not experiencing such a boom. This is quite a large effect, especially when compared with the unconditional sample mean and volatility of labour productivity growth of 2.1% and 4.3%, respectively.

Financial booms are not, in general, growth-enhancing. And, the distributional nature of the impact is disturbing, as credit booms harm what we normally think of as the engines for growth – those industries that have either lower asset tangibility or high research and development intensity. This evidence, together with recent experience during the financial crisis, leads us to conclude that there is a pressing need to reassess the relationship of finance and real growth in modern economic systems.

Disclaimer: Views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily those of the BIS

See original post for references

Correlations are easy to find. Causation is hard to prove.

My hunch is that speculative booms are a symptom of the dearth of sufficiently profitable investment opportunities in the real economy relative to the accumulated funds. Rather than being a “drag” on the economy, then, their presence is an indicator of underlying sluggishness. They may even add a bit of superficial oomph to the sluggish economy relative to what it would otherwise be.

” speculative booms are a symptom of the dearth of sufficiently profitable investment opportunities in the real economy relative to the accumulated funds”

Perhaps, but how is saddling the population with debt and paying compound interest to unproductive bankers adding “oomph” to a sluggish economy? I would argue speculative booms are the result of too much money being in too few of the wrong hands, i.e. an already wealthy investor class looking for easy returns from financialization instead of true entrepreneurs who are interested in building something real, or regular joe consumers who can buy regular things like shoes, meals, cars etc. and stimulate the real economy.

Rather than investing in other people’s work with the intent of making money for themselves, these same people should perhaps take their own money, put it behind their own efforts to create a business based on a product/service that they have some part in creating.

Like the article says, investment opportunities have a place in an emerging economy, but outside of that the parasitical nature of people/institutions who have no other skills rather than riding on other’s accomplishments become a burden that causes the sluggishness. That these same parasites exhibit no apparent self restraint to avoid starving the host shows that they need to be significantly restrained.

A strange version of the paradox of thrift, perhaps? Just accumulated capital rather than savings…

As J W Mason over at Slackwire has explained in detail, the run up in private and household debt in the post Volker era has not been the result of consumers and businesses borrowing more: it has been the result of de-regulated finance imposing higher interest rates. The era thought of as that of “low interest rates” has been so only for large financial institutions who, while themselves enjoying historically low rates, have managed to charge the rest of us what was once considered usurious rates.

Had this rate advantage for finance coincided with an era of more efficient investment in the real economy this could have been beneficial. Instead it has coincided with a liquidationist attitude to the real economy that has off shored everything imaginable, not for efficiencies, but as regulatory and labor arbitrage, creating no real economic benefit except to increase the profit share of income at the expense of the wage share.

The results speak for themselves, vast publicly supported mal-investment schemes at least since 2008 when mark to market was waived for finance and QE begun to support the cash flows the mal-investments need to spin off to not be revealed for what they are. China’s market can at least still crash, between the trading desk at the Fed, ZIRP and QE, ours can’t. How can you call this a market? It certainly isn’t Capitalism.

Great comment.

Maybe the Investor Class has so overplayed their hand that now is a good time to think seriously about a whole lot of debt cancellation, stuff like marking to market the house of my friend who is in foreclosure due to lost job, a house that Wells Fargo won’t approve even a full-price sale on as they work the bubble machine to demand even more pounds of flesh, and hang my friend out to dry. Because “market”?

It’s not like reduction of impossible debt, odious debt and corruption-induced debt that kills people and their political economies has not been done before, even a little bit with respect to those lazy Greeks and their corrupt officials and oligarchs, (‘So Many Bribes, a Greek Official Can’t Recall Them All,’ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/08/world/europe/so-many-bribes-a-greek-official-cant-recall-all.html?_r=0) and is even bruited about by “serious” economists as being a good thing (in appropriate circumstances with full protection for their sponsors’ interests, of course).

“Does Debt Forgiveness Work? Ask Africa,” http://www.huffingtonpost.com/marcelo-giugale/does-debt-forgiveness-wor_b_5318764.html

“Debt of Developing Countries,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Debt_of_developing_countries

“International Debt Forgiveness and Global Poverty Reduction,” http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1799&context=ulj

It’s a mechanism that’s certainly been studied and talked about and applied, here’s link of links that might interest anyone not tied to the Strictitude of Luther and Calvin: https://www.globalpolicy.org/component/content/article/210/44795.html

And one may not want to call it Capitalism, but not to start a category combat, what we got is very definitely what I think the common folks understand by that word.

Debt > consumption > debt > consumption — any way to break the cycle? Or all its other parts, perpetual war and people “needing” 16 “homes” and saying they have a “right” to use all the potable water they want to maintain the perfect greeeeen of their lawns and “plantings” and replenish the losses from their “water features,” because “they can afford it,” especially because as a Major User they get a much lower (subsidized by the rest of us, what a surprise) rate?

It certainly isn’t capitalism, I think of it as ‘reverse socialism’. BTW, great comment.

When a larger portion of income goes toward the servicing of debt, less income is available for productive use/real capital investment.

Take private debt for instance. Buy a house at boom inflated prices and less income is available for anything else

I take from this that the “wealth effect” is counter-productive? On a small scale relevant to my small life, say an investor in seattle decides to buy some rental houses, finacialism over a booming decade increases asset value significantly so rent is increased also significantly, while worker with no assets needs to apply more productivity to cover that with no associated increase to the asset free individual, reducing buying power? I notice the author cites reinhart/rogoff 2010 so wondering here what the more financially savvy readers take from the article

I was an investor, SFR rentals would be the last place I’d put my money. Just give Leigh Robinson’s book, Landlording, a read. If you still want to be a landlord after reading it, you’re a very brave soul.

Takeaway from the book: Tenants are not very easy to deal with. And that’s even before we get to any discussion of what they can do to your property.

Oops! I meant to say “If I was an investor…”

I was a landlord for a short period over a house I rented out when I left the military and moved elsewhere. The tenant was a friend and even then it wasn’t peaches and cream, not leastwise for being a distant landlord. I’d do it again under the right circumstances if I knew the tenant (was a friend/acquaintance or family) OR if it was an apartment within my own home so I was right there all the time. Still, landlording does suck to varying degrees. It never doesn’t suck. It can only be made to suck less in the right circumstances.

But then I was also a human being and didn’t try to rape my tenant with bullshit overpriced rent. All I was interested in was enough to cover the mortgage payment plus extra to drop into a home maintenance account to deal with any problems that fell under my responsibility.

Far be it from me to say a large financial sector is good (I’d much rather have manufacturing, which there isn’t much of in the USA anymore), but I’m not very impressed with the data. Sure, the stats express a mathematical measure of correlation, but look at the point cloud. Not very convincing. There must be a lot of other, stronger effects (not that I know what they are).

I saw that too. Not that I disagree with the premise of the article, but the data aren’t that convincing.

Remove 3 data points from each extreme and the line would very likely take on a significantly different slope. Either the extremes are noise or the huge centroid mass of buckshot is loaded with noise.

I certainly agree that finance is a drag, not a benefit. Simply look at the past periods when economic growth was strong, corporate and household debt was reasonable for everyone, and finance was a fraction of the size it is today (from WWII until the mid-70s). As finance has become THE focus of the economy, the economy has gone anemic, productivity is measured by layoffs to drive up stock prices rather than actual improvements in products or services. THAT is causation right there.

Comparative advantage also keeps popping into my head, financialism creating more for itself by blowing a bubble here and shaving the top off there, thus no currency rules in tpp for instance, while greece is left to hang because they can’t create any comparative advantage, because they are in a union which comparative advantage is baked into the cake and favors other countries?

There is now considerable evidence that productivity grows more slowly when a country’s government, corporate or household debt exceed 100% of GDP (see Reinhart and Rogoff 2010, Cecchetti et al. 2011, and Cecchetti and Kharroubi 2012).

Reinhart and Rogoff 2010? You mean “Growth in a Time of Debt”? Citing that paper is problematic at best.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/05/02/reinhart-rogoff-austerity_n_3201453.html

The way I see it, when your bankers resemble the mafia (except on a far vaster scale, and with government influence the mafia merely dreamed of), you’ve got a problem.

~

++++++ to infinity and beyond!

Yes. The 2010 R&R paper has been debunked.

It’s fantastic to see this documented empirically by a economics professor but this seems like plain common sense to the un-indoctrinated. Basic access to credit is needed in developing countries where entrepreneurial types have great business ideas and there is a genuine unmet demand for many products and services. But in developed countries where everything is already built out and everyone with the means already has a car, a washing machine, a television etc. more bankers, more financialization simply equals more debt. More debt equals more of your money that could be used for productive things instead going into the pockets of bankers as compound interest. Too many ticks eventually kill the dog. Why is this very simple and intuitive concept revolutionary for economists and those who have attended Business School?

One aspect of financial sector growth is assured: concurrent growth of debt. The declining increases in productivity identified by the authors supports the view that financial sector/debt growth is along a continuum that leads from increased productivity in its initial stages toward increasing levels of financial asset and real estate speculation in its latter stages, finally culminating in a “Minsky Moment” when (absent additional infusions of money into the system) it suddenly becomes evident and widely recognized that cash flow from the assets/debtors is insufficient to service the debt and there is a sudden major collapse in asset values and writedowns in the debt that supports them. Setting aside related issues of massive fraud and deception to create a perception of value, I believe this is what happened in the dotcom bubble of 1999, the real estate bubble of 2007, and what is presently occurring on the Shenzhen and Shanghai stock exchanges discussed elsewhere in today’s NC blog posts.

A related characteristic is the declining velocity of money as money/credit/debt proceeds are increasingly channeled into and tied up in speculative bets on increasing financial and real estate asset prices that are in their final stages virtually indistinguishable from Ponzi schemes.

What I haven’t reconciled is how consumer debt-fueled purchases of goods and services fit into this framework.

Yes, but I submit the large jump on the Fed’s balance sheet following 2008, followed by QE eternal has erased the “market” aspect of our system: it is now so managed by, for and of the banks that they operate, at least within the terms of the system, risk free.

This is to say our banks are anit-Capitalist, or has been said on this site frequently, communism for the rich. As you point out, with wages flat and everything else slowly inflating, debt has gone up for consumers, but you should read the Mason paper ( http://slackwire.blogspot.com/2012/02/dynamics-of-household-debt.html ) as it shows this was not a result of consumers increasing their use of debt, but because of increases of applied rates and penalties/fees in the “de-regulated” era.

Wage income, in the era of de-regulation was turned into rents owed Capital by the expedient of putting constant pressure on income while charges and rates escalated for the slightest household financial inconsistency. As the penalties and interest accrued, more and more of the flat wage share came to be owed to finance and drained away from expressing demand in the real economy.

Maybe honorable mention in the Impoverishment Sweeps goes to that unmeasured inflation in the costs, er, prices, of necessities, like food and shelter and transportation. Works several ways: over a year or so, e.g., first one, then another corporate processor of Orange Juice discovered that “consumers,” out of habit, would continue to “pick up a half gallon of orange juice, honey,” even though in increasingly smaller and less contrasty and more obscure print, the “legal” product volume shrank from 64 to 59 ounces, same price. The boxes themselves are slowly shrinking to accustom the rest of us to “the deal.” Outrage? Shrug.

Mentioned that to a guy at the OJ section in the grocery store, he shrugged, smiled, and said, “That’s just marketing.” I asked him his line of business: “Marketing,” he said. The recipe for tuna spread on the current Ritz cracker box calls for “one 6 ounce can of tuna.” No such thing, except in specialty brands, for at least a decade — maybe 4 ounces, after the regulatorily-captured “legal draining time.” Same “price point.” And Ritz? the cracker has shrunk, and there’s a lot of air space in the package for a largely incompressible silo-stacked cracker that does not “settle in shipping.”

Crapification, and this is how Chained CPI will appear, magically, de facto…

What you’re describing isn’t “virtually indistinguishable from Ponzi schemes” it IS Ponzi finance plain and simple. What Ponzi finance and high loads of consumer debt have in common is easy money or an over-abundance of credit. The over abundance of credit inevitably leads to Ponzi finance. Concerning 2008, the “Greenspan Put” unleashed a wall of liquidity for speculative purposes and the funny money derivatives of Wall Street (MBS & CDS together being the most effective ) flooded the market with easy credit when bankers figured out a way to decouple credit risk from lending. (in the short term anyway) As soon as the traditional banking model of make a loan to a credit-worthy entity then recoup principle plus interest for a profit went out the window and was replaced with originate a loan by any means necessary to any willing party, then sell the paper to Wall Street for a quick profit, repeat, repeat, repeat as fast as possible, a giant bubble ending in tears was inevitable. Now think about the effect of of seven years of ZIRP and counting.

Ah yes, a Ponzi scheme indeed, but one being run by the Fed, the issuer of a fiat currency in all the forms that can be injected directly into financial markets.

So they’re not really markets at all anymore, just one giant politically run Ponzi scheme: its the perfect scam so long as the US military and police state can enforce it!

Inexpensive fiat is not the problem but that it is created for special interests such as the banks instead of for the general welfare only.

Expensive fiat, such as a gold standard, is simply an older scam foisted on the public.

Borrowings from the government-subsidized private credit cartel break the natural balance between borrowers and savers and for an understandable reason – why should one have to save, perhaps for a long time, mere money units if there are idle resources NOW?

That said, there are surely more just ways to introduce new purchasing power into the economy than government subsidized private credit creation.

I cannot help but to be skeptical of this given that the “surprising” results in past work (Cecchetti & Kharroubi BIS working paper) have been artefacts of the math they use (ex. “showing” finance to have a negative effect on real growth by using an equation that necessitates a negative correlation regardless). I am not saying that they have false conclusions, but, rather, that the arguments are less than satisfying once you dig down a bit.

Finance is a utility function in a balanced economy, but it grows past that role to become the deadly parasite we know today. I would suppose that change could be associated with a number of societal downfalls over time, where a social service function displaces critical functions like agriculture. Between the malignancy of modern finance, and the bloated military, productive social functions are choked off. No money for education, civic development and infrastructure, medical care. Sounds way too familiar.

While I don’t doubt the correlation, I somewhat question the cause – that financial growth tends to underfund riskier industries in favor of those with more certain, if a bit boring, assets to collateralize, which I read as a preference for mergers and acquisitions over product development. Looking at the explosion in financial products and schemes, mostly over the past 20 years I believe the primary driver of financial growth has been risk shifting – and much of that risk shifting was accomplished through fraud (AAA – rated bonds that were truly junk). While this financialization frenzy created growth as developers built McMansions for burger flippers, it was not sustainable. I have no prior knowledge of Cecchetti or Kharroubi, but their perception of causation seems to ignore the darker aspect of financial sector growth – fraud, and its impacts on the growth of the larger economy. Still, I like that highly respected folks are questioning the paradigm that financial system growth is good for an economy.

Why? Let me ask the multiple former NASA employees and other engineers I personally know who are now working for GS…

Just looking at velocity of money is some evidence to support the author’s claim how capital held within the banking system has little value to the economy at large. Would this be austerity in disguise?

This might explain some of the strength of Silicon Valley: if the finance sector in general leans away from knowledge-intensive production, then having a highly developed special investment route (venture capital) for that purpose would give Silicon Valley an advantage over rivals who are more dependent on the finance sector in general (and its inability to properly value intellectual assets and production).

I’m supposed to read deep into the article after it cites the work of Reinhart and Rogoff (2010)?!

Those two poseurs have been readily discredited; by a grad student, no less.

You beat me to it Gio. I was surprised that Reinhart and Rogoff was referred to as well, that study was discredited by some pretty basic excel errors to push an ideological agenda. Can’t believe those two still get airtime but that’s the economics profession for you.

But I think the premise of the article still stands that a growing finance sector hinders an advanced economy. I view a large banking and finance sector as a parasite and ‘tax’ on the real productive sectors which produce actual things. When there is a symbiotic relationship things are ok, but when parasites get too big they end up killing the host…

That is my point of view as well. Finance produces nothing in and of itself and therefore is a cost on actual production so any increase in finance relative is going to be a drag on useful production. Using employment all employment in finance is a drag on productivity since finance produces nothing. If finance were operating with fewer people and at a lower cost then all other things being equal productivity must be higher. Isn’t that just math?

Growth of parasites is usually at the expense of the host.

Isn’t it possibly just the case that, similar to our personal and household budgets, when our debt levels exceed some fairly modest level, we end up spending up our resources just paying interest to our creditors. IOW, it’s extremely easy for the creditors to become mainly parasitical rather than helpful, hence all that condemning of usury in several of our religious texts.

OT: In those scatter graphs (not just the ones above, but in general), the line drawn through them, it’s slope and exact placement, that’s not really scientific, is it? Always seems pretty impressionistic to me.

Regarding the line drawn on scatterplots such as the one above, its slope and placement. It is a mathematical product, not impressionistic art. It is the objective result of certain mathematical operations, whose interpretation depend on the validity of quite a few assumptions regarding the origin of the data scattered about.

The particular mathematical method is called simple linear regression and it seems not exactly the right thing to do considering the nature of the scattering of the data; it seems something more elaborate is needed for a more rigorous interpretation, for better exploitation of the data.

Oops, sorry. Should have read the comments section first. I was repeating what several had already said.

Well . . . in a sense that may go to show that it was glaring enough for several people to independently notice it. And that in itself is “anecdata”.

If a tree falls in the forest and nobody is there to hear it, does it make a sound?

If I grow and eat a tomato without having to buy it, did I ever even grow it at all?

If I trade my backyard tomatoes for my neighbors zucchinis and no cash registers ring, did said trade ever even take place?

I get a feeling that the term “real economy” is restricted to ” the money-denominatable economy”. People buy and sell mass amounts of real production and real service for money. It is a real economy.

And the financial economy has certainly reached a dangerously parasitic size on the real economy. But there is an economy beyond the money-denominated real time-is-money hamster wheel economy. And it could be called the Ecosystem or the Biophysical Economy. The place where roofwater is harvested and stored, houses are warmed by letting sunlight into them through windows, people grow backyard food, etc.; all without any money changing hands.

If the FIRE sector parasiticonomy lords dominate the real hamster wheel economy for now, perhaps some people can partially retreat into the ecosystem-based biophysical economy of subsistence production for use or trade. And THAT economy can still grow a little bit. There’s big UnMoney to be made in the growing Counter Economy. Unspending is one of several waves of the future. At least for some. Perhaps for many.