Yves here. This post is important, and despite getting technical at key junctures, nevertheless makes some important points worth digesting. One is that the various discussions of “Greek debt sustainability” by economists and the IMF use different notions of what “sustainabilty” means. The IMF notion of sustainability is that a borrower can eventually finance itself in the capital markets at a borrowing cost at which it can afford to service its debts. Other commentators have used different (as in more permissive) standards.

However, as the post points out, analysts, particularly the IMF, fail to incorporate tail risk into their projections adequately, and that’s a gaping lapse since “tail risk in the new normal”. Not surprisingly, Greek debt looks unsustainable when you make more realistic “bad things are bound to happen at some point” assumptions.

By Andrea Consiglio, Professor of Mathematical Finance, University of Palermo and Stavros A. Zenios, Professor of Finance and Management Science University of Cyprus. Originally published at VoxEU

Some experts view Greek debt as sustainable, while others claim it is not sustainable. This column argues that the distinction between tactical and strategic debt sustainability can explain this difference of opinions. Moreover, strategic debt sustainability analysis should account for tail risk. This approach shows that Greek debt is highly unsustainable, but sustainability can be restored with a nominal haircut of 50%, interest rate concessions of 70%, or a rescheduling of debt to a weighted average maturity of 20 years. Greece and its creditors should ‘bet on the future’ and embrace debt relief.

Who is Right?

Holding a national referendum on a highly technical document on debt sustainability is indicative of the confusion among Greek (and EU) politics in the midst of a never-ending crisis. It is also indicative of some confusion over what debt sustainability analysis tells us.

How could we have conflicting conclusions on the sustainability of Greek debt by credible analysts with access to the same data? For instance, Paul De Grauwe argues that the “Greek debt is sustainable” (De Grauwe 2015), whereas the recent IMF report finds that the “debt could not be considered sustainable” (IMF 2015).

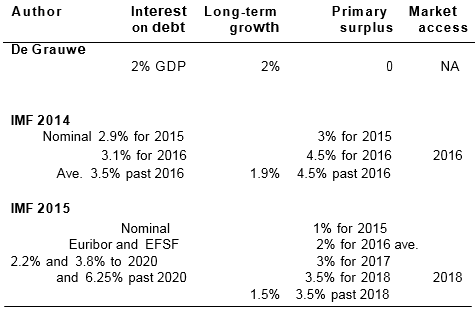

One explanation stems from different assumptions about growth and debt refinancing rates. This is of course, obvious, and it is not the point of this column, but let us digress briefly to highlight in Table 1 the key assumptions behind these conflicting findings. The assumptions of the IMF led to “a high probability that […] debt is sustainable” (IMF 2014). Within a year, reality trampled these expectations and the IMF changed its verdict to “not sustainable with high probability” (IMF 2015). The IMF’s chief economist Olivier Blanchard discusses lessons learned from their mistakes (Blanchard 2015), but readers were unconvinced. Mody (2015b) retorts that “Professor Blanchard writes a Greek tragedy” and that creditors dealt “in bad faith”. Wolff (2015) comments on the failure “to recognise two major IMF mistakes”. In particular, it should have been obvious that a sustained primary surplus of 4.5% with 1.9% growth is just a “surplus of ambition” on what an economy could achieve, as readers of Eichengreen and Panizza (2014) would recognise. Indeed, the IMF repeatedly revised downwards its growth projections during the Greek crisis.

So, once the IMF dropped its unrealistic assumptions, it declared debt unsustainable, while De Grauwe, with an assumption of modest growth, finds debt sustainable. What is going on? Is there a flaw in one of these studies? The answer is no.

- They are both correct but they are answering different questions, and this is the first point we make.

Table 1. Key variables in sustainability analyses of De Grauwe (2015) and IMF (2014, 2015).

Tactical and strategic debt sustainability

De Grauwe looks at current contractual terms for interest payments. Under the concessionary terms provided by the creditors the interest payment is 2% of GDP, and with 2% growth (and a balanced budget, of course), Greek debt remains stable at its current level. This is what we would call tactical sustainability. Tactical analysis does not consider a return to the markets. Or, implicitly, it assumes a return to markets at the rates of the official sector. It answers the following question: Is debt non-increasing under current conditions? If yes, all is fine. However, if there is a large payment due immediately, then we are facing a tactical decision for a bridge loan. In the case of Greece, payments of €2 billion due to the IMF were missed. But according to De Grauwe’s analysis, this poses a liquidity and not a solvency problem.

The IMF considers that refinancing debt over its horizon will eventually require access to markets “at an average nominal interest rate of 6% for the next several decades”. This is strategic sustainability and reaches a different conclusion.

The tactical view is valid while a country is under an adjustment programme financing its needs with contractually fixed terms. The strategic view is important when the country graduates from the programme and is financed from volatile capital markets.

This distinction explains a contentious point between the Greek government and the IMF on one hand, and the EU creditors on the other. The EU creditors do not discuss debt relief as, in the short run, there is a liquidity problem that can be solved with a 3-year bailout programme and a bridge loan. They are making a tactical decision. (This is the economic argument; politics come into play as well.) However, this does not guarantee that Greece will successfully graduate from the programme even if it diligently swallows all the prescribed austerity. Successful graduation means a return to the markets, and the strategic analysis tells us that debt is unsustainable. The IMF is right in asking for debt relief and this should come at some point during the 3-year programme. If it does not get its wish, Greece “will shuttle between the emergency room and rehabilitation”, to quote Mody’s apt analogy.

Watch the tails

Now take a deep breath and read the IMF’s 2014 caveat: “uncertainties […] make it difficult to categorically affirm that debt is sustainable with a high probability”. Which are the uncertainties, what is the meaning of “difficult” and how high is “high probability”? (If the German public was asked to vote on such an evasive statement, most likely they would have given a louder disapprobation than the Greeks.)

In a recent paper we find the caveat is valid, thus anticipating the 2015 IMF report (Consiglio and Zenios 2014). This was not the objective of our paper (of course). Instead, we argue that debt sustainability analysis should incorporate tail risk. While IMF reports are replete with terms like “uncertainties” and “probability”, no effort is made to quantify them.

- For crisis countries, the tail is the new normal and ignoring it is ignoring the essence of the problem.

This is the second and main point of this column.

We model the distribution of the debt-to-GDP ratio and define a risk metric termed CDeaR–Conditional Debt-at-Risk. This is the expected cost of debt assuming that cost exceeds a threshold percentile (e.g. 0.95). This is the cost of financing debt at the tail of the distribution. Scenarios of the risk factors are used to estimate if debt-to-GDP ratio decreases with time, both in the mean and in the tail. A linear programme optimises alternative debt restructurings, thus identifying sustainable and unsustainable profiles.

The case of Greece

The model was applied in March 2015 to analyse Greek debt using 2014 data. We consider GDP growth and primary surplus assumptions from IMF (2014) and from the proposal of the Greek government for a primary surplus of 1.5%. The most important departure of our work from previous analyses relates to debt refinancing. We assume that Greece will re-access the markets with the same rates as Italy, and projections are generated using a simulator developed for the Italian treasury. The risk horizon is 20 years and confidence level 0.95 (for details, see Consiglio and Zenios 2014).

Three findings are relevant to the current debate:

- With the surplus and growth projections of IMF (2014), we find debt sustainable.

If one believes the 2014 assumptions, then our analysis verifies the IMF statement: “categorically affirm that debt is sustainable with a high probability”. However, these assumptions were hard to swallow and the IMF abandoned them.

- If Greece were to run a balanced budget, enjoy a long-term growth rate of 1.9%, and re-access the markets at the same rates as Italy, its debt-to-GDP ratio will keep increasing from its current level of 180%. Debt is unsustainable.

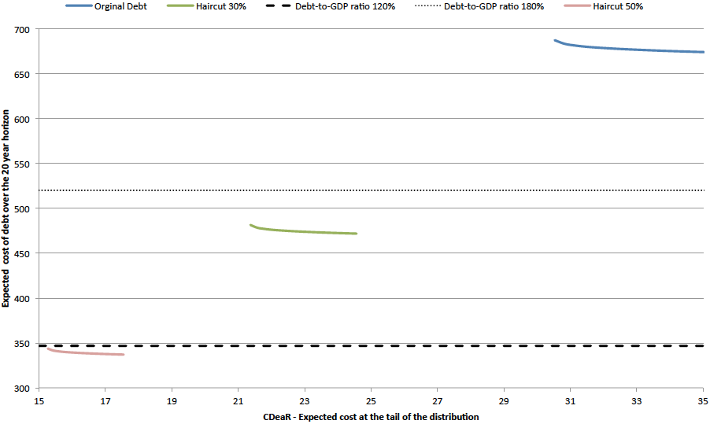

Results in Figure 1 with different nominal value haircuts lead to the following observations. First, a nominal value haircut of 30%, as suggested in IMF (2015), significantly improves the situation, but does not bring the debt-to-GDP ratio below 120%. Second, a haircut of 50% brings debt-to-GDP below 120% and is sustainable. This is close to the 66% haircut suggested in Mody (2015a) without formal analysis. His insight is correct although it prescribes a somewhat higher haircut than what is essential.

- If Greece were to run the primary surplus suggested by its government and enjoy enhanced short-term growth, the situation improves significantly.

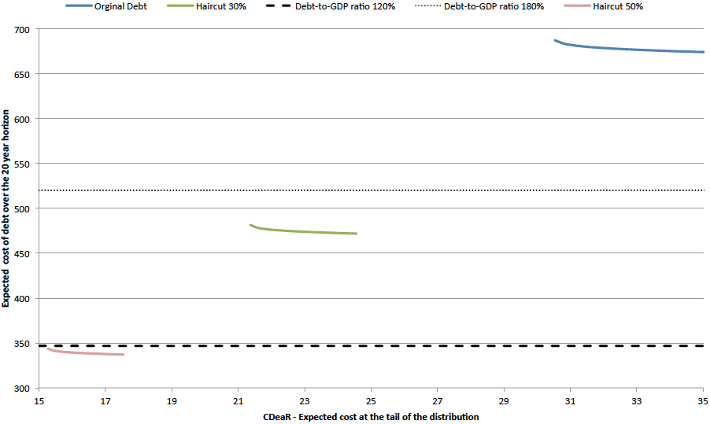

From Figure 2 we observe that the debt-to-GDP ratio significantly improves over the current 180%; with interest rate concessions of 70% (i.e. Greece pays only 0.7 of the interest) the debt-to-GDP ratio drops below 120% and is sustainable; and sustainability is also achieved by a debt rescheduling such that the weighted average maturity extends to about 25 years from its current value of about 14.

Figure 1. Risk profiles for financing alternative structures of Greece debt under balanced budget

Conclusions

Policymakers need to consider tail risk in debt sustainability analysis. The tails of the distribution hold information that can make or break the conclusions of their analysis.

An application to the case of Greece confirms that its debt is unsustainable. Sustainability is restored either with an upfront nominal value haircut of 50%, or interest rate concessions of 70%, or maturity extension by about 10 years. Our findings are in broad agreement with the latest IMF analysis, and provide additional credibility since they hold true with high probability. However, it is worth noting that this analysis was carried out using 2014 data and, hence, it shows that the IMF erred in declaring debt sustainable in 2014. Our analysis, carried out in March 2015, anticipated the IMF’s 2015 analysis and was not affected by the policies of the new Greek government. Hence, the IMF cannot blame the debtor for the revision of its debt verdict from sustainable to unsustainable. No matter how misguided the negotiating tactics of the Greek government might have been, debt was unsustainable before they came to power.

A Recommendation

What does this analysis tell us about the Greek saga?

With high probability, we can say that the country needs debt relief. This can be in the form of interest rate concessions and the rescheduling of debt obligations. However, debt relief should not be postponed to some indefinite future. Adopting the tactical view that debt is sustainable fails for two reasons. First, the country does not see any light at the end of the tunnel and the politics of reform worsen. Ownership of the programme is key to its success and it is hard to claim ownership of a programme that succeeds in its tactics but fails in its strategy. Second, much desired foreign direct investments cannot be attracted to a country during the programme if it is highly probable that the country cannot graduate from the programme. The IMF is right to refuse to join a programme that does not include debt relief.

Figure 2. Financing Greek government debt for varying concessions on interest payments or re-profiling with maturity extensions

Greece and its creditors should now ‘bet on the future’. Bazerman and Gillespie (1999) argue for the virtues of contingent contracts. Such a contract fits the Greek crisis like a glove. Agreement on debt relief cannot be reached right now; there are genuine differences of opinion on debt sustainability, there is lack of trust and the politics are unfavourable in Germany and northern EU countries. Instead of aiming for an agreement now, the differences of opinion should form the core of a contingent contract for debt relief. Withholding the disbursement of funds without prior actions is the stick that creditors wield. Contingent debt relief is the carrot; contingent on a successful first year IMF review and the debt-to-GDP ratio remaining above the current level, a pre-specified debt relief clause becomes effective. Our analysis shows what this clause could entail.

Please see original post for references