Yves here. We’ve focused on how the operational issues of going to the drachma involve considerable delays and costs that look to more than outweigh the oft-claimed advantages. This post describes another set of complexities and costs: that Greece will often come out the loser as far as its efforts to force redenomination of contracts from euros to drachma are concerned.

By Sebastian Edwards, Henry Ford II Professor of International Economics at the University of California, Los Angeles. Originally published at VoxEU

Many commentators continue to think that Greece’s best bet is Grexit and the drachma, but few are talking about what will happen to contracts. This column uses Franklin D Roosevelt’s devaluation of the US dollar to give an historical perspective on currency devaluations and contract litigation. Roosevelt got away with it because the Supreme Court ruled that prices in old contracts were void and, importantly, because everyone trusted the Supreme Court’s rulings. Grexit would mean litigation in international courts – courts that are likely to side with the plaintiffs.

A number of commentators continue to think that Greece’s best option is to exit the Eurozone and reintroduce the drachma at a depreciated level ((e.g. Brinded 2015). Those that favour this policy argue that with a currency of its own and exchange rate flexibility, Greece would gain competitiveness, increase exports, and move towards recovery.

This view, however, ignores the effect of such a policy on contracts. Almost every contract in Greece is written in euros – labour contracts, suppliers’ contracts, debt contracts (private and public), service contracts, investment contracts, and so on. After the reintroduction of the drachma, will these contracts be enforced in euros (the original currency agreed by the parties) or in the new (depreciated) currency? This issue is important even if Greece is granted considerable debt forgiveness.

In principle, the legislation that would reintroduce the drachma could also state that contract originally written in euros would be converted into new drachmas, at a depreciated exchange rate. Creditors, however, will cry foul and will turn to the courts in an effort to receive payments according to the original contracts, in hard and convertible euros.

Greek courts are likely to side with the government, and declare that the old contracts are void and that the new drachma could be used to discharge debts and other obligations. But in a globalised world, domestic courts usually don’t have the last word. Litigation will move to international courts and arbitration tribunals. As a member of the EU, Greece has to abide by EU laws and regulations, and creditors will flood European courts with all sorts of claims related to the annulment of euro-denominated contracts.

Greece has also signed bilateral investment treaties with 39 countries, including Germany, Russia, Korea and China. Thus, any attempt to change the currency of contracts will end up in arbitration at the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes, the World Bank’s tribunal for investment disputes. This is, indeed, what happened in Argentina after it devalued the peso in 2002 and ‘pesified’ contracts. In most cases, the Centre ruled for the claimant and ordered Argentina to pay large compensation awards (on Argentina’s crisis and devaluation, see Edwards 2015a).

But Argentina is not the only historical antecedent that is valuable for understanding what may happen if Greece decides to exit the Eurozone. Another interesting case is the US in the 1930s, when President Franklin D Roosevelt took the country ‘off gold’ and devalued the US dollar by 41%.

The Abrogation of the Gold Clauses in 1933

In April of 1933, and in the light of a major banking crisis and a severe run on the currency, President Roosevelt – who had been in power for little more than one month – decided to declare a gold embargo and take the US off gold. He also decided to devalue the US dollar, mostly as a way of increasing agricultural prices.

However, there was a serious problem with this plan. At the time, virtually all of the public debt and a very large amount of private debt – railway and public utilities’ bonds, and mortgage debt – was denominated in ‘gold coin’, and were payable in specie or its equivalent in paper money. In total, over $100 billion of debt was gold-denominated – nominal GDP at the time was $66 billion. President Roosevelt decided to deal with this situation by asking Congress to “abrogate the gold clauses”. And that is what Congress did on 5 June 1933 (for an analysis of this episode, see Kroszner 1999).

On 31 January 1934, and after a transitional period where a number of unorthodox policies were tried, President Roosevelt officially devalued the dollar by 41% and fixed the new price of gold at $35 an ounce (since 1834 it had been $20.67). In explaining the decision, Roosevelt said that the devaluation was necessary, since the nation had been “adversely affected by virtue of the depreciation in the value of currencies to other Governments in relation to the present standard of value”.1

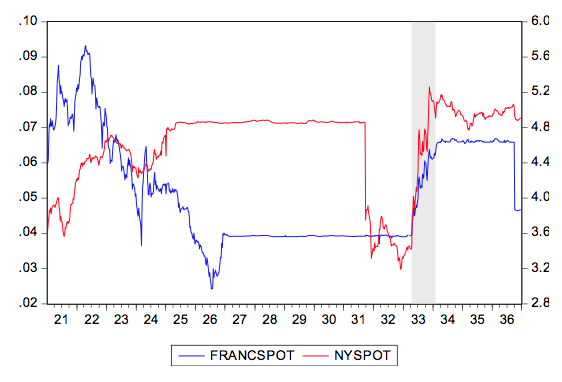

In a recent paper I discuss in detail the process that led to the devaluation of the dollar (Edwards 2015a). In Figure 1, I present weekly data on the US dollar/sterling and US dollar/French franc spot exchange rates between 1921 and 1936. Both rates are in the form of ‘dollars per unit of foreign currency’. This figure captures:

• The return of Britain to gold in May 1925;

• The re-pegging of the franc to gold in late 1926;

• The abandonment of the gold standard in April 1933;

• The period of a ‘managed’ currency between April 1933 and January 1934; and

• The adoption of the new dollar gold parity in January 1934.

Figure 1. Dollar-sterling and dollar-French franc exchange rates, weekly, 1921-1936

The 1935 Supreme Court Rulings

Investors that had purchased securities protected by the gold clause claimed that the Joint Declaration of June 1933 was unconstitutional, and various lawsuits were filed.2 Four of them got to the Supreme Court and were heard between 8 January and 11 January 1935. The first two cases had to do with private debts. One referred to a railroad bond (Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co), and the second to a mortgage debt secured by a bond denominated in Gold Dollars (United States v. Bankers Trust). In the railroad case, the bond was a 30-year obligation issued on 1 February 1930 with a 4.5% coupon payable “in gold coin of the United States of America of or equal to the standard of weight and finesse existing on 1 February 1930”.3 On 1 February 1934 the holder of the bond asked to be paid $38.10 corresponding to the semi-annual coupon, at the new price of gold. The issuer argued that it only owed $22.50.

The third case involved a government bond in the series of the Fourth Liberty Loan issued on 15 October 1918. The obligation for this “4.5% Gold Bond” expressly stipulated that “the principal and interest hereof are payable in United States gold coin of the present standard of value” (Perry v. United States). The holder of this bond asked to be paid $35 per troy ounce of gold. The Treasury refused, and made a payment in paper dollars using the old parity of $20.67.per ounce of gold. The fourth case referred to a Gold Certificate (Nortz v. United States).

The Supreme Court ruled on 17 February 1935. In all cases the vote was 5 to 4 in favour of the government’s position. However, the majority used different arguments to decide the public and private debt cases.

In the private debt cases the majority, led by the Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, pointed out that according to the Constitution, Congress had the power to conduct monetary policy – more specifically, under Article 1, Section 8, Congress had the power to “coin Money, [and] regulate the Value thereof.” Thus, based on this constitutional prerogative, Congress could invalidate private contracts – including the gold clauses – if they interfered with such power.

In the Liberty Bonds case, the majority used a different reasoning. According to the opinion, which was also written by the Chief Justice, Congress could not abrogate the gold clause for government debt. The reason was that although Congress was allowed, under the Constitution, to regulate the value of money, it could not use that power to invalidate obligations arising from another of its constitutional powers, the power to borrow money on the credit of the US. Thus, concluded the majority, the abrogation of the gold clause for government debt was unconstitutional. However, the Court added, since gold holdings by private parties had been forbidden since April 1933, if the claimant received payment in bullion, he would be obliged to sell it immediately to the Treasury at $20.67 an ounce. Thus, even though the abrogation of the gold clause for government debt was unconstitutional, there were no damages.

There was a single dissent signed by the four conservative members of the Court. It was delivered by Justice James C McReynolds, who said: “The Constitution as many of us understood it, the instrument that has meant so much to us, is gone”. He ended his allocution with strong words: “Shame and humiliation are upon us now. Moral and financial chaos may be confidently be expected.”4

In spite of Justice McReynolds’ sombre statement, after the Supreme Court rulings the economy didn’t collapse, nor did uncertainty take over. In fact, the Treasury had no problem issuing new debt, nor did it have to offer higher yields to place it. The reason for this was that in the US there was a highly respected and credible institution – the Supreme Court – whose ruling was final and accepted by all parties. Moreover, very few foreign investors were affected by the modification of contracts, and even those that incurred in losses had no recourse at the international level.

This, however, is not the case in Greece. As noted, if Greece decides to exit the euro and abrogate contracts, there will be, with all likelihood, a multitude of lawsuits that will be heard by international courts and arbitration tribunals. As in the recent case of Argentina, these courts are likely to rule for the plaintiffs, adding a considerable cost to the Grexit strategy.

See original post for references

How’s about Greece counter suing the EU for extortion and Gold Sacks for fraud? I’d say they have a pretty good case.

I’d like to say “I’m shocked, shocked that International Creditors will resist accepting freshly printed Drachmas as a replacement for payments on invoices and debt presently denominated in Euros.”…..

Good history review, of ground that’s also covered in Milton Friedman’s Monetary History of the United States.

When Britain devalued sterling in the autumn of 1931 (plunging red line in the chart above, representing a soaring dollar), what had been a US recession turned into a depression. Deflation carried on at 10% annually, accompanied by a fresh wave of bank failures.

Although devaluing the dollar against gold was effective (indeed, probably it was the sole effective thing Frank Roosevelt did), it wasn’t necessary to ban private ownership of gold to achieve it. The minor windfall that would have accrued to holders of gold bonds wouldn’t have undermined the economic boost of devaluation. Instead, the Supreme Court let the US government welsh on its obligations, in its first and only technical debt default.

Unlike the self-dealing conflict of interest in the US, where judges on the fedgov payroll enforce (or not) the fedgov’s contractual obligations, Greece is subject to external court rulings. As the author states, courts are likely to hold Greece liable for its original obligations in euros, much as a US court held Argentina liable for the full dollar value of defaulted bonds under New York law.

What then? It’s not bloody likely that European creditors would invade Greece to seize assets. Greece can ignore their court rulings and carry on as a pariah state, in the manner of Iran, Argentina and other states that get excluded from the good graces of international respectability.

It didn’t have to be this way, and it isn’t for most countries. Greece’s plight is the poisoned fruit of the euro currency, which may yet claim more Club Med victims.

@Jim Haygood – One point of the article is that Greece can’t ignore court rulings by European Union courts. Doing so would violate the treaties and – what was left unstated – effectively see Greece leave the EU.

Agreed. Dr Schaeuble called it a 5-year time out. But it likely would last longer.

Most likely it would be five years rolling. That is, it would be five years from any date you pick, including any future dates.

In the case of the US, Supreme Court judges are backed by H bombs. That’s a big “advantage” we have over the less exceptional countries.

Bingo! All this is happening because Greece is weak, economically and militarily. The talk about courts is all hogwash. The US got hosed in the courts over the mining of Nicaragua’s harbors–how did that turn out, hey? Meaningless bullshit because it was unenforceable. Greece can be taken, so it is taken. Courts are just a fancy instrument for exercising control by powerful interests. They have power in inverse proportion to the power of those they claim to hold jurisdiction over. The weak get screwed. The strong skate. End of story.

Did Argentina pay those monies the ICSID-World Bank tribunal ordered?

Mr. Levy, you understand, I think, the real configuration of the elephant in the room.

Without a very different organizing principle, our species, let alone the little groups we favor, are well and truly phukked…

The judges can slam their gavels all they want. Sovereigns can and have defaulted at will, superior to any law or legal system.

Honestly while I agree with NCs computer code / “Code is Law” analysis, I think appealing to softer things like actual legalities is just more “chaos”-type thinking. Grexit, like the next California big one, is possible, and we won’t be stopped by people marking ink on pens.

Huh? Argentina paid the IMF in full. And if you bothered to read the post (you clearly didn’t or didn’t read it carefully) this is about the redenomination of private as well as public contracts.

And your assertion is flat out false. Sovereigns do not walk away from their debts. They renegotiate them. And even Argentina has just ‘fessed up it’s going to have to pay the vulture investors even though just about every bankruptcy effort deems the decision by Judge Griesa to be batshit.

In early 2002, Argentina redenominated US dollar mortgages into pesos, first at one-to-one and a little later at 1.40 pesos to the dollar. That ended up being a favorable rate for mortgagors, since the peso soon fell to 3 to the dollar. But they were still angry.

Banks ate the forex loss. Some of them (e.g. Bank of Boston) just beat a retreat out of town, as protesters trashed their branches with graffiti reading RATAS (Rats!), CHORROS (Thieves!), and YANKEES (too vulgar to translate). Photo:

http://tinyurl.com/q4zfy7a

More recent, and much more relevant example. Hungary (which is in EU, so subject to EU laws) forcibly redenominated CHF mortgages that banks provided to Hungarians right left and centre, at rate hugely bad for the banks. Off the top of my head I can’t remember how the court cases ended (or even whether it was just quietly swept under the carpet) – but most of non HU banks now exited HU I believe.

I think your point Yves, is that creditors would resist being paid in Drachmas, if the Greek government voluntarily exited the Eurogroup and tried to introduce their own currency, and that the EU courts would undoubtedly support them.

But, what if Grexit is forced by the creditors? Would the result be the same or different?

Would not the creditors have some obligation to ease the transition to the Drachma after forced Grexit, including some form of technical assistance program and payments such as Schauble suggested to Varoufakis? “How much would it take to get you to leave?”

Would any assistance include negotiating some relief favorable to the Greek government regarding debt payments to creditors that would have been forced by the EU onto Greece, by forcing them out of the Eurogroup against their will.

That’s a very different scenario politically than Argentina unilaterally deciding to devalue the Peso and causing harm to creditors who then sued, which is the equivalent of voluntary Grexit, but NOT forced Grexit.

Some effort along these lines would seem to be necessary politically to shift the blame for failure onto the Greeks. “See? We’re being nice and reasonable. After we killed the patient we kindly arranged the funeral and even paid the widow for some of her expenses.”

How did they deal with the switch TO Euros?

A while back there was an article by an Irish author reminding us that Ireland had changed currency 3 or 4 times, ending with adopting the Euro. How were those handled?

My point is that currency changes happen all the time. There must be loads of precedent. Has international law changed recently?

Of course, the underlying question here is, again, sovereignty. I think we agree that countries that joined the Euro, or even just the EU, gave up significant sovereignty. The remaining question is whether that was truly irreversible. Again, countries subdivide pretty regularly – the next will be Scotland. They will have to set up their own currency. Is that now impossible?

And equally of course, the real test is one of the large indispensable economies: Italy, Spain, France. The next election in any of those could lead to an exit. So the real question is, just how much hits the fan when that happens?

The decision to move to the Euro was decided by treaty, eight years before the switchover started, and that took a full three years. They was plenty of time to redenominate contracts. No one would want to be left trying to invoice in dead currencies, so there was ample incentive for private parties to make the adjustments. By contrast, Greece going to the drachma does not eliminate the euro, and anyone who benefits from contracts staying in euros would insist on the euro-related terms remaining in force.

Yves, I don’t think that answers the question? First, there are some contracts that have terms longer than 11 years.

But more importantly, the issue isn’t time. The issue is that matter of if one (or both) parties don’t want to re-denominate. At a conceptual level, why is that a meaningful bottleneck?

Introducing a national currency unit is, by definition, for the benefit of the national economy. By definition, a sovereign nation controls the domestic legal system. So the only way there are legal barriers is if the government isn’t sovereign, or if the problem isn’t domestic.

I agree the drachma doesn’t solve Greece’s international problems. I have been consistently critical of proposals trying to finagle the international problem, like the TAN idea. No form of domestic IOU can satisfy debt denominated in a foreign currency – just like $20 and an ounce of gold ceased being interchangeable when FDR devalued the dollar to bail out the banks (that’s why the EO to turn in gold was issued before the devaluation – so the gold would be in the banks. If the point was merely to devalue the currency, they could have skipped that first step.) The unwillingness of many people to accept that fundamental tenet of reality was fascinating earlier this year when various proposals were being floated for Syriza to try. Indeed, that’s why US gold reserves dropped dramatically from the high in the 1950s – foreigners wanted euros, not drachmas, so to speak.

But the drachma is a potential defensive response if a foreign power tries to sabotage Greece’s domestic economy in response to Greece renouncing its euro-denominated foreign debt. In such a scenario, legal issues are moot, because Greek actors are defaulting on those euro contractual obligations, not re-denominating them.

When the euro was introduced, the old currencies were turned into fixed denominations of the Euro, so there was no need to re-write contracts, it was (is) still officially the same currency, like dollars and cents. Introduction of a new floating currency while the Euro still exists is an entirely different matter.

A really interesting post – this issue gets very little coverage, and it should. It would seem that leaving the euro would require that Greece renounce everything and join the ‘pariah’ nations like Russia, Argentina, and Iran etc. in a trading block of some kind.

Or perhaps the only answer is for Greece to acquire nuclear weapons and threaten MAD. Modern financial instruments would seem to be nearly as lethal… If the alternative is national suicide, well…

A final thought. There is a lot of chatter about the embargo on Iran being ended. But perhaps: allowing Iran to be ‘integrated’ into the world financial system would in the long run be even worse than being bombed! Perhaps Obama is even sneakier than we imagine…

Sure. A Made in China Government Motors Cadillac in every Iranian driveway financed by EX-IM Bank, after privatizing the bank by giving it away to Goldman or JPM. A free year’s supply of Viagra to every buyer – just to piss of the Mullahs.

A plan computed by the Top Secret 11 Dimensional Chess Quantum Computer at Langley.

Huh? Joining a trading bloc solves none of these problem. Greece is not sovereign in the ruble or the renminbi. It still has all the same problems with IT and legal agreements of converting to a drachma irrespective of who its trade counterparties are.

It’s depressing, but I’m asking everyday if there is any solution for Greece’s problems? Staying in the EU seems to leave it tied to the whipping post of slow death. Leaving the EU involves a logistical and legal nightmare of figuring out what to do with contracts, payment systems, exchange rates, printing presses, and lawsuits. It would seem that the country has entered into a complete and total trap of Fraco-German design and it’s people suffer as a result.

Perhaps Greeks should simply pull up stakes and move en masse to France, Germany, Finland, and Norway. Create immigrant towns in their cities of the north and get on public benefits. It might be the only way for Northern leaders to cut them a break.

This, among other reasons is why I have long advocated that Greece impose “Force Majeure” on it’s treaties with the EU, and adopt the GEURO – Greek Euro.

Greece can claim that the policies imposed by the Troika are insane – using the criterion established by Albert Einstein: “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over, expecting different results”.

Greece can claim that all of the debt under consideration is odious, and void.

Greece can stand on it’s feet as a sovereign, pass laws that make interference with it’s adoption of the GEURO, a criminal offense punishable by DEATH, then send out commando teams to abduct The head of the ECB, bring him to Athens, put him on trial for killing greek diabetics and cancer victims, and burn him at the stake!

Greece can put a $1,000,000 GEURO reward for the return to Athens of each and every lawyer submitting lawsuits, each and every plaintiff, and each and every judge hearing same, DEAD or ALIVE!

Greece can peg the GEURO to the EURO, route all forex transactions via a Greek ExIm bank, and make the GEURO a restricted currency ala the Reminbi/ South African Rand, Namibian Dollar, Malaysian Ringit, ie no free trading on FOREX, all settlements via Currency Swaps.

Greece can use the GExIm Bank to effectively shut off imports from Germany/ France and anyone else with whom it trades at a disadvantage via structural impediments.

Greece can take control of it’s internal payments system, firewall it from that of the EU, and keep it’s domestic economy going.

Greece can impose 6 yrs of national service on all greeks from 18-24 years, effectively eliminating youth unemployment, mobilizing this pool for service at below minimum wage to the nation.

Greece can impose taxes on debt instruments, effectively creating demand for GEUROS among it’s creditors, as they struggle to pay the 10% / month tax on their principal, and can use this tax to force it’s domestic banks to hand their loan portfolios into the FinMin for GEUROS at face value, effectively recapitalizing them.

Greece can eliminate fractional reserve banking by forcing domestic banks to invest 100% of all deposits into Greek savings bonds of varying maturities for savings and Greek Treasury Notes for demand depositsa, which effectively makes the monies paid for domestic Greek Bank Loans, most of which are non-performing, go right back to Treasury for the purchase of bonds.

Greece can forgive the loans and / or force conversion of the property into lifetime tenancy in exchange for forgiveness.

Most of all, by acting like a sovereign, Greece can quash any and all lawsuits as they arise. It will only take Draghi being burned at the state to send the message “dont mess with us”.

Lastly, Greece can abrogate all lease agreements for NATO bases, imposing $20 billion annual fees, imposing $100/ phone call eavesdropping tax on NSA, and seizing US/NATO assets to collect.

INDY

armchair warriors…(to dr. george)…ever have to walk away from a battle leaving behind someone to die because the current arena was not conducive to a victory…???

why don’t you start by going up and down third avenue and get the rest of the armchair warrior greeks in brooklyn to put together 50 million to capitalize 8 new banks in hellas ???

oh…that might take real work…and all those thousandaires might miss a car payment…

war is easy to talk about for those well past their selective service registration sell by date…

in the morning somebody has to drive the bus…and the trucks to make sure the cereal makes it to the store shelves so the children can have breakfast…

hmmpppfff….

I have a question. Could Greece use odious debt to challenge at least some of the debt that Greece has had to pay? It seems, based on my amateur reading of the issue, that at least some of the debt could be challenged and written off.

I’m quite surprised to see an article on this subject without any reference to “Lex Monetae” in it.

The currency a contract is written in is not relevant. What is relevant is the jurisdiction. If the contract is under greek jurisdiction then it can be redenomitated in anything Greece wants, any time. There’s no argument here. Every decent internationl law firm knows this, and even if they didn’t it wouldn’t matter cause it will be ruled by greek courts.

Lex Monetae does not apply if the contract is not under national jurisdiction, like the Argentinian example you make, or like the greek contracts which Greece was forced to change from national to foreign law by the troika to access previous bailout programs.

Usually, those who advocate the Grexit are well informed on the Lex Monetae matter.