By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

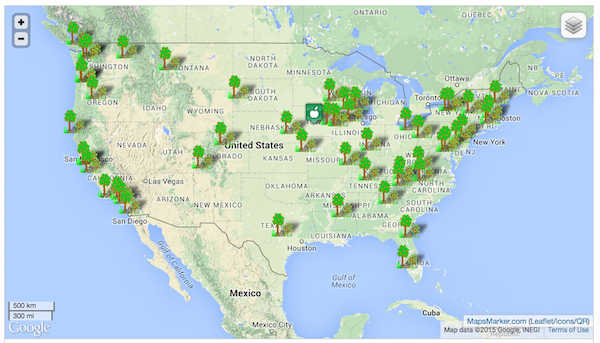

Well, by a variant of Beveridge’s Law — “Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no” you would guess the answer is “I don’t know,” but in fact my answer is “A lot more than I would have imagined just a few years ago,” and that’s a good thing. An IndieGogo fundraiser to “Help us get to as many sites as possible to learn directly from the pioneers of the community food forest movement” closed unsuccessfully, alas, but one of the organizers, Catherine Bukowski, went on to collect some of the information, and mapped it:

So I have to surrender my idea that “These permaculture types are so focused on the site specific that they can’t generalize,” but they sure don’t make it easy; in fact, I only came up with Bukowski’s map after a considerable search, in which I gave up once; all the other lists I can find are just random, with no pretence of being even close to exhaustive.[1]

And so the answer to the headline question is: More than 54, probably fewer than 100, certainly fewer than 1000. So why focus on edible forests? And what is an edible forest? And who creates them?

Why Focus on Edible Forests?

Perhaps idiosyncratically, I believe that horticulture (as opposed to agriculture; see Jared Diamond, “The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race”) is an activity that’s intrinsically worthwhile; considered rightly, even one of the arts, like painting, or music, or poetry. 1491‘s author, Charles Mann, says that some anthropologists consider Amazonia — very large portions of which are an edible forest — “a cultural artifact,” perhaps the world’s largest. And indeed, a garden may share many characteristics with art: Beauty, survival for more than one generation, persistence and enterprise, skill in the making, including sensitivity to the use of materials.

Perhaps more importantly, food is power. We saw in Greece how the financial powers-that-be were able to leverage their control of the payments system[2] to enforce their political goals; but that control would surely have been less absolute than it was had Greece been able to feed itself, as the likelihood is that Greece is not, since then food security would have been less closely coupled to the payments system required for imports. For example, up here in Maine we’re at the end of the line; thirty or forty miles north of me are the woods — hmm! — and Interstate 95 turns into a two-lane blacktop road. Problems in circulation — whether slowly choking arteries, or infection[3] — hit the peripheries first, and if or when “the trucks stop,” I would like Maine to be able to feed itself.[4]

Finally, although you can most definitely create your own edible forest on even a very small patch of land, most edible forests are on public land. I think public goods are to be encouraged in principle where found, as a counterweight to the ruling neoliberal ideology of “because markets.” The whole principle of an edible forest is that people can pick and eat for free — in fact, that’s exactly what people do and should do in the raspberry patch that I have grown — and that just isn’t a market-based thing; edible forests are much more like common pool resources.[5]

What Is an Edible Forest?

I’m going to give this operational definition, sourced to Gaia’s Garden by Toby Hemenway, not because it’s the only possible defintion, but because it creates a very clear picture in my mind of the possibilities (and, though I say it, the beauty):

The Seven – Layer Garden

An edible forest is a layered garden. The seven layers of a for est garden are tall trees, low trees, shrubs, herbs, ground covers, vines, and root crops. Here are these layers in more detail.

1. The tall-tree layer. The tall trees in an edible forest are mostly fruit and nut trees, such as apple, pear, plum, cherries, ch estnuts, and walnuts. There needs to be lots of space between the trees to let light in to the lower layers.

2. The low-tree layer. The next layer is made of smaller trees, such as apricot, peach, nectarine, almond, and mulberry. Dwarf varieties of bigger trees are also good choices for this layer. These trees can be pruned to have many openings to let lots of light through to the lower layers.

3. The shrub layer. This layer includes flowering, fruiting, and wildlife-attracting shrubs. Examples include blueberry, rose, hazelnut, and bamboo.

4. The herb layer. The “herbs” in an edible forest are plants with non-woody, soft stems. They can be vegetables, flowers, cover crops, cooking herbs, or mulch crops. They are mostly perennial, but sometimes gardeners choose to plant a few annuals .

5. The ground cover layer. These are very low plants that grow close to the ground, such as strawberries, nasturtiums, and thyme. They are very important because they make it difficult for weeds to grow.

6. The vine layer. In an edible forest , some plants, like grapes and kiwis, grow up the trunks of the trees.

7. The root layer. A forest garden grows both up and down. The last layer is plants that grow underground. These should be plants with shallow roots, like garlic and onions, which are easy to dig up without disturbing the other plants.

(In my own tiny practice, I have planned for #3, and not even thought about #6 (vines) or #5 (ground cover). #5 is especially important to me because weeding is work. I don’t like work.) And (as NC readers know) you don’t need a lot of land to start one:

Derived from woodland ecosystems and incorporating layers of fruit trees, nut trees, herbs and perennial vegetables, root plants, ground cover plants and a vertical layers of vine plants, forest gardening is a low maintenance and sustainable gardening system that also yields a useful food supply. You needn’t have a lot of land to start your own forest garden – you can begin with a space as small as 30 ft x 60 ft and up your acreage from there. Armageddon? Bah.

And in the same way that I’d like to abolish the lawn, I’d also like to abolish the “Home and Garden Center” (since the big box stores tend to bring infection with them from out-of-state, too). Why not learn from the best?

Forests are the perfect design

With 460 million years experience, and a 9.6 billion acre garden, Mother Nature has refined the way to grow self sustaining gardens better than anyone! No weeding, spraying or watering!!!

Nature has supported, fed, clothed and sheltered humanity for 95% of its existence – agriculture only first emerged 10,000 years ago.

It stands that Nature is obviously the best (and only!) model available for us to imitate for growing gardens.

Of course, mimesis is very far from a literal transcription….

Who Creates Edible Forests?

Here, I’ve collected a number of projects (not all of them on Bukowski’s map). One thing that struck me about the tone of the news stories on edible forests was their resolute normality[6]; they were presented as forms of civic engagement and covered much like fund-raising projects for libraries, or Fourth of July parades, or the Kiwanis sale. Further, many projects were instigated, from the bottom up, by entrepreneurs whose sense of industry had taken that form. (Frankly, there’s a good deal of that in the permaculture community, with trainers charging for courses and so forth, but I don’t see a better alternative to get stuff in the ground today; waiting around on foundation grants doesn’t seem like a good idea, for example, and Common Pool Resources don’t have a lot of clout, at this point, in state institutions.) The twin characteristics of utter normality — with an exception I’ll get to — and bottom-up civic engagement strike me as very good characteristics for edible forest propagation.

Since the projects all have varying social engineering issues, I’ll just go state-by-state in alpha order and comment as I go:

Florida

Florida Gulf Coast University has an amazing program (far more interesting to me than their professional NCAA sports teams. From the university’s site, though cloaked in administrator-ese, here it is:

The FGCU Food Forest works to advance the mission of the university through offering unique and innovative educational and service learning opportunities for students, alumni, staff, faculty, and community members and through enhancing awareness of sustainable food production and whole food nutrition. Furthermore, the Food Forest seeks to elevate the environmental sustainability of the institution through providing organic fruits and vegetables to the campus and southwest Florida communities. Ultimately, through engaging the hands, hearts, and minds of students, alumni, staff, faculty, and community members, the Food Forest will offer a space for the cultivation of lifelong learning and for a commitment to sustainable food and living practices.

The food forest rates not one but two awesome (and note the very typical focus on saving gas money):

Lacey Lind 9/29/11

Seeing the progress it’s made is exciting. I’m excited for it to be officially up and running. I think that by putting a food forest for the students to gain access to for free is really awesome. It saves trips to the grocery store, and gas, and money. The fact that it is fresh means that it can only be healthier for you. It’s not covered with bad chemicals or pesticides. It also is a better source of food because it’s not processed. Everything about the food forest is one-hundred percent natural. I like how it is the student body that came together and built this from the ground up. It’s really awesome. Also, I like how precise they are with what types of soils they use, and how the forest is put together in order for preservation. The food forest is built for self sustainability. It should be able to survive on its own for a certain amount of time with no upkeep. The other thing I enjoyed about this opportunity is I learned tips and tricks that I can use if I decide to build my own food forest. I really like to see how much of a love people have for our environment. We really need more people like that, because I think it would gain us a little more time on this Earth.

Thank you so much again! Yay food forest!

And here’s a good national goal from a practitioner:

A good friend of Arlo Simonds, a student of environmental studies at Florida Gulf Coast University, first introduced him to the concept of a campus Food Forest in 2011, just before members of the Food Foresters Club broke ground for their permaculture project. “When I was a freshman, my friend brought me to a couple of planning events and eventually, I was hooked,” says Simonds, who is now a senior, president of the club and its service learning coordinator.

Simonds is active in the Southeast branch of the Real Food Challenge, a movement that leverages the power of youth and universities to create healthy, fair and green food systems. Their primary campaign is to shift $1 billion of existing university food budgets away from industrial farms and junk food towards local or community-based, fair, ecologically sound and humane food systems—“real food”—by 2020. “We’re hopeful that the movement can take hold here, because it has had success at other universities,” advises Simonds.

Shifting a billion dollars out of bad food into good food (and good food-growing practices) is clearly a worthy goal. University administrators: Pay attention!

Iowa

From The Gazette in Cedar Rapids, Iowa:

In a few years, visitors to Noelridge Park in Cedar Rapids, Lowe Park in Marion and Wetherby Park in Iowa City will be able to pick an apple or a pear to snack on, free of charge.

Local groups are planting the fruit trees to create “edible forests.” The trees are saplings now, but in years to come they’ll provide food to anyone walking by.

Urban food forests are growing in popularity nationwide, part of a wider focus on eating food grown close to home, orchard organizers say.

” think as a society right now people are paying really close attention to the mileage of the food they’re eating,” says Dustin Hinrich, field coordinator for Marion-based Trees Forever. “People recognize the fact buying apples from Chile is foolish when we grow very good apples here in Iowa.”

I think it would be a splendid innovation if candidates campaigning in Iowa started visiting locally-driven and entrepreneurial projects like these, in addition to meat-heavy spectacles like the agriculturally focused Iowa State Fair. Campaign staffers: Pay attention!

Michigan

From the Traverse City Ticker in Northern Michigan (though not the Upper Peninsula):

After raising more than $5,000 on crowdfunding website Indiegogo, a network of environmental and land use groups planted two stretches of edible forests along the TART Trail system last year. The Cedar Lake and Cedar Creek Food Forests will eventually feature jostaberries, hazelnuts, elderberries, blueberries, sweetfern, mulberries, persimmons and several other varieties of fruits and nuts that are free to be enjoyed by anyone using the Leelanau Trail.

Owner Stuart Campbell of Perennial Harvest – a partner in the project – says the group will next turn its attention to other potential planting sites along TART, including Jupiter Gardens near the corner of Rose and Boyd streets. “We’re looking at pitching an ‘Adopt-A-Berry,’ similar to an ‘Adopt-a-Mile,’ where businesses or people could adopt a certain stretch of the trail (for planting),” says Campbell. The group is also pursuing grants and other funding sources and hopes to develop a website of resources that can help other communities plant their own edible forests.

Note the funding source and (again) a local entrepreneur (but and so I hope the website doesn’t suck too many resources, as they tend to do; see note [1]). And I like the “Adopt-a-Berry” idea — privatized though it may be — very much, again because of its resolute normality.

Michigan is also, of course, the home of Detroit, which is famous for turning the vacant lots produced by neoliberal policies into gardens (and also farms, although horticulture is not the same as agriculture). Unfortunately, I couldn’t find an example, in Detroit, of a food forest per se. (And here I will pause to note a distinct bias, at least in the photographs of permaculture projects I have seen, toward “middle class” white people, often in Birkenstocks or similar. I’m not sure why that is — and I don’t think it has to be — but I would suspect access to land, private and public, has a lot to do with it; for example, the property I use was inherited, and inheriting property is something that black people disproportionately do not do. And I would imagine that access to public land in, say, Ferguson, would be easier for some than for others). All this said, I’m including Detroit as an allied example exactly because of property issues. Consider one neighborhood, Brightmoor, and the Brightmoor Farmway project. From their site:

Urban gardens and farms play an important role in the City of Detroit. They provide hundreds of thousands of pounds of fresh, nutritious fruits and vegetables for families and strengthen our communities by connecting neighbors, providing an attractive alternative to trash-strewn vacant lots, improving property values, and reducing crime.

And here’s what Brightmoor has done:

The Brightmoor Farmway, which winds its way about nine blocks through the four-square-mile-area on the city’s northwest side, is full of gardens, orchards, sculpted landscapes, pocket parks, and even goats, chickens and bee hives.

The nature trail residents blazed through the area runs through one of the few wooded preserves left in the city and in part runs adjacent to the Rouge River — a natural wonderland indeed.

But who owns the land? As it turns out, the City of Detriot has big plans. From newly hired city planner Maurice Cox, who previously worked in New Orleans:

Brightmoor’s vacant land can be turned into productive acreage that works for both its remaining residents and those in nearby Rosedale and Grandmont.

What constitutes “productive” land? Cox said empty lots in Brightmoor will be remade for recreation, nature, agriculture or so-called green and blue infrastructure, with engineered plots of land with plants and trees to dispose of stormwater or alleviate air pollution. Along with its blight, Brightmoor already has some of the most extensively developed agriculture in the city. Cox said Brightmoor residents eventually will benefit by living near carefully landscaped property, including parkland and wooded areas, rather than amid the wild and trash-filled parcels that mark many parts of the landscape now.

“We will have a strategy of how to steward that land, that vacant land within the city, and make it contribute to why someone would actually want to live in Grandmont-Rosedale,” Cox said.

Whenever I hear statements “we have a strategy,” I ask who “we” is, and whether the locals have been consulted. Not necessarily. From the Metro Times:

On the Facebook page of the group Neighbors Building Brightmoor and the Brightmoor Farmway, a message was posted concerning about 100 parcels they had been told they’d be able to bid on that were part of that bundle:

All of NBB’s vacant land was put in the blight bundle by the County treasury and the Detroit Land Bank. We were assured we could buy it later from them, since no one was going to buy this according to them. Well, it was sold, I don’t know by whom, but many of our farmers are left with pieces of their land no longer available to them and many of our parks now have pieces of land that belong to God knows who… the Chinese, the Japanese, Saudi Arabians? 6,000 properties in Detroit in one fell swoop snatched up by someone we don’t know.

One commenter on the thread posted: “How sad!!! Why would you try to disrupt the neighborhood like that? This is so wrong!!!” Another declared: “selling all of these far flung properties to one buyer is beyond ridiculous. Whose bright idea was that anyway??”

The Brightmoor folks sound like good examples of conscientious Detroit homeowners, people who own their land, their homes, precisely because they want to be in a good position to determine what’s going to happen with their neighborhood. When outside, anonymous forces are given free rein to buy such unrealistic bundles of property, they have every right to feel threatened.

Indeed. And remember that all public land can be privatized, and since local politics is all about land use, insiders will know before the rest of us (“I seen my opportunities and I took ’em.”) So, as in Detroit, all such Common Pool Resources will have to be defended from those who would plunder them.

Massachusetts

Here’s a food forest in Mattapan, a Boston neighborhood:

As a brutal winter retreats into the record books, Bostonians of all species are out and about. “Mating sparrows, wild turkeys, hunting hawks, they’re all around us as we work,” says Orion Kriegman, Director of the Boston Food Forest Coalition. On the idyllic grounds of the Boston Nature Center in the Mattapan neighborhood of Boston, neighbors work to prepare the Boston Food Forest for its second growing season. After only one year, the Food Forest is well stocked, boasting 34 young fruit and nut trees, with 45 more to join them in 2015. Though the most plentiful harvests are years away, the Food Forest is already yielding a stronger community and a fine model for economic and environmental justice in the city.

(I’m not sure I like that “years away” very much. It might make more political sense to include immediate concrete material benefits; as in food for the hungry from annuals to be phased out later, for example.)

And in the Berkshires, Hugel culture. (I’ve tried hugel culture in a small way, with scraps from my firewood; it works great, so I’m quoting extensively on the technique in case readers which to try it.)

All along the side of the yard of the former Notre Dame rectory Berkshire Earth Regenerators planted an extensive “hugel” bed, employing a large amount of natural wood debris already in need of disposal on the property.

“We basically planted it in a day, and walked away,” said Lamb of the installation, which can now produce hundreds of pounds of food with minimal tending.

“Regenerative is a better term than sustainable,” Allard of this kind of agriculture, “We don’t just want to sustain where we are now.”

Nice framing.

This first phase of several planned at the Shire City Sanctuary includes over two dozen different foods, including corn, radishes, lettuce, tomatoes, asparagus, squash, peas, carrots, beets, broccoli, chard, sprouts, cucumbers, plantains, potatoes, beans, melons and more within one long, tiered row of mutually beneficial ecosystem.

Hugelkulture (from “hill culture,” pronounced “hoo-gul culture”) employs a layered mound system that holds moisture and maximizes surface “edge” ecosystem, increasing soil fertility progressively each year. The mound beds store and better utilize rainwater, and wood debris used in their installation provides long term nutrition for the array of plants. Through this method, practitioners aim to not only exponentially increase the yield volume of vegetation relative to both space and labor hours, but do so in a way that improves rather than depletes the soil in which they’re growing.

The initial hugel bed planted at Shire City cost less than $200 in seed and supplies.

Berkshire Earth Regenerators say they’re looking to expand this model into partnerships with other public and private properties to create a beautifying, easily maintainable “forest of food” in small pockets throughout the extensive acreage of open space throughout the city. Hoped for collaborations with parks and local schools would provide not only a great source of locally sourced food for cafeterias but also offer great educational benefit, something Allard and Lamb said is crucial to their overall mission.

“Plant in a day and walk away” … That’s my kind of gardening, because (I think I’ve said this) I don’t like work. (Of course, it seems that the real work in this area is engineering the social systems around the edible forests so that they continue to be supported).

Texas

Here’s a proposed project in Texas from the Dallas Morning News, and you’ll see from the first paragraph why I flagged this as a departure from the resolute normality of the other projects:

While it sounds a little hippie-dippie for conservative Collin County, a park near McKinney could become the site of the nation’s largest public “food forest.”

A what, you say?

That’s a plot of land planted with a variety of fruit and nut trees, berries and other edibles to provide a renewable supply of free food for residents and serve as a model for sustainable [or “regenerative”] gardening.

“It would be a showplace for Collin County,” said Stephen Kallas, a member of the advisory board for Myers Park, a 158-acre county park and event center that highlights the area’s agrarian heritage.

As the board considers future plans for the park, Kallas proposed establishing an edible forest garden on an undeveloped 60-acre section.

“This land is sitting fallow and not being utilized,” he said.

(The acreage was a former soccer field; said the County Extension Agent: “You can’t grow anything there.” Part of the problem…) The board turned Kallas down, but asked him to come up with a less ambitious plan. And despite the “hippy dippy” remark, the Morning News went on to say:

The use of public lands for edible forest gardens is a growing trend throughout the country.

In Seattle, the Beacon Food Forest, started in 2009, provides 20 to 40 pounds of free produce each week during the growing season.

In Sonoma County, Calif., a nonprofit organization called Daily Acts has partnered with municipalities to create small food forests at Petaluma City Hall, at parks> in Windsor and Cotati, and at the city hall-library complex in Sebastopol.

(Sounds like the reporter had the same problems getting an overview of how many edible forests there really are as I did!) Here, note the continuing themes of “free food” on public land — and if your standard for public land is “highest and best use,” isn’t free food high on the list? — as well as a local entrepreneur driving the process. (Kallas has already created a edible forest on his — “his”? — own land.)

Washington

Finally, from Seattle, WA, the Beacon Food Forest:

The BFF is a lush public garden where all of the produce is up for grabs [that is, “free”]. Instead of dividing the land into small patches for private planting, like most community gardens, volunteers cultivate the whole food forest together and share, well, the fruits of their labor with anyone and everyone. Urban foragers are welcome to reap what the community sows.

A food forest is pretty much what it sounds like: “A woodland ecosystem that you can eat,” says Glenn Herlihy, one of the BFF’s founders. A food forest mimics how a wild forest works, but swaps in species that are edible or otherwise useful to humans and other animals. Fruit trees and nut trees cast shade (on sunny days) over berry shrubs, herbs, and veggies, while vines climb up trunks and trellises. Underneath, healthy soil teems with tiny life, storing carbon, water, and other nutrients necessary for plant growth. The BFF leans on permaculture farming, which uses ecological design and a bit of good ol’ human labor to create multi-species gardens that bring forth mountains of flavorful, nourishing grub without fossil fuels or other polluting substances.

At about two acres, it’s already the largest edible garden on public land in the U.S. And it’s a wildly prosperous example of the real sharing economy.

Importantly, the BFF is managed as a common-pool resource. (That’s why I’ve focused only on edible forests, as opposed to “community gardens,” or “urban farming” (which I’m not sure is a thing, and if a thing, not necessarily a good thing; I think Grist’s headline — “These urban farmers want to feed the whole neighborhood — for free” — is just plain wrong, starting with the fact that horticulture is not agriculture).

Conclusion

So there we have it. It looks to me like edible forests are here to stay, and more than here to stay. It also looks to me like “free food from public land” is being treated, well, with resolute normality. (Perhaps the neo-liberals haven’t noticed it, yet!)

Of course, we can’t feed a whole continent or even a state with around a hundred food forests, but it also looks to me like edible forest projects are scaling nicely; as a movement, it seems to be spreading rhizomatically, with practitioners sending out roots and stalks in onesies and twosies, but in the aggregate multiplying to cover the field, like my g*******d Scotch thistles, but also like hops, asparagus, ginger, irises, Lily of the Valley, Cannas, ginger, and turmeric, all of which are highly beneficial.

Winter is coming; I hear crickets now, and the usual blights are sadly visible now that the tomatoes and winter squash have set fruit. Perhaps instead of looking at seed catalogs next to the fire we can consider a little social engineering instead? Focused on local land use?

NOTES

[1] I do think, however, that the field is to some extent hobbled by a generic problem of information sharing: The onus is on the time-pressed and, if not actually impoverished, very far from being poverished practitioner to share, and I would bet most see that as interfering with the direct provision of services. Bootstrapping a process where people share information with unknown others for unknown returns is often very hard to do.

[2] I feel that leverage was aided greatly by people taking the payment system, and especially the ATM, as a sort of public service, as something almost natural, like air or (mostly) water. You put your card in the box, and money comes out. What could be simpler? Power relation? What power relation? Volcker famously remarked that that “the most important financial innovation that I have seen the past 20 years is the automatic teller machine. That really helps people and prevents visits to the bank and is a real convenience.” But that’s not all it does, as we see from Greece.

[3] Yes, I know that Avian Flu doesn’t infect humans. Good thing, eh?

[4] Another reason “trade deals” are insane. We really should not optimize for Chinese vegetables — or any other vegetables than our own — coming here in shipping containers and refrigerated trucks from thousands of miles away; we should optimize for food production right here.

[5] Elinor Ostrom lists eight characteristics of Common Pool Resources; I think the only one that does not yet apply is #8: “Nested enterprises. Appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution, and governance activities are organized in multiple layers of nested enterprises,” for CPRs that are part of larger systems. Perhaps when the number of edible forests increases by an order of magnitude, we’ll see these nested enterprises emerge.

[6] On resolute normality: See the coverage of permaculture projects in Ithaca, NY, or Chichester, NH.

Open for comments, but please stay on point. I’d love to hear about your own projects, no matter the scale!

I doubt places like my garden are counted. Many of us with forest gardens in urban/suburban areas are discreet, as we worry that local authorities might one day come and remove it all with backhoes and bulldozers. I alleviate this by putting the most attractive elements out front supplemented with many roses, spring bulbs and wildflowers. Even so, some acquaintances who have driven by and some neighbors further down the street have told me my place looks “overgrown”. Contrarily, people who walk by and can see it up close praise me on how beautiful it is with all the flowering herbs, butterflies, and the depth that the layers provide. This in the Chicago area.

I also allow people to pick fruit and berries (to my wife’s chagrin). I want people to know that (1) food does not actually come from a supermarket and (2) what one can grow oneself is infinitely better than one can buy at the farmer’s market much less a supermarket. When I was young families with different fruits shared across the season and I expect this to return as more people grow them.

In just 1/5 acre I have 3 Persimmon, 3 Paw Paw, 5 Pear, 7 Apple, 7 Plum, 4 Peach, 4 Apricot, and 1 Medlar trees, many gooseberries and currants, blackberries, blueberries, figs, goumi, goji, 14 grape varieties, hardy kiwis, strawberries, and a hazelnut hedge plus many culinary and medicinal herbs. There are also 4 jujubes, 3 pomegranates, chinquapins and other plants still in large pots. Separately there is an intensive vegetable garden. I hope my efforts inspire locals as to what one can do. Some members of our local garden club are adding more edibles, having toured mine. Last week a passerby told me she would also grow a “wilderness” if she had the time.

That’s impressive!

You’re right about people changing their minds when they see it up close; one of the several stacked functions of my raspberry patch is a diplomatic face to the town…

Lambert, this is maybe not the best but rather, my favorite post on Naked Capitalism in quite some time. Thanks!

You’re welcome!

Re local authorities (and I would add homeowners’ associations) I’d urge everyone to do what they can to change the ordinances/rules to explicitly allow these types of gardens. Being on the boards for two associations I know the nice lawn paradigm still dominates. And contrary to what some here believe, city councils and homeowners’ associations have little choice about enforcing the rules as written. Of course if you prefer you could just get rid of homeowners’ associations (fine with me) but the city governments will be tougher to deal with.

It used to be that permaculture classes advocated “chop and drop” and such methods for permaculture, but a new awareness of aesthetics is growing. Beauty is now recognized as an inextricable aspect of design for urban settings, and I can see some permaculture businesses growing up to specialize in that.

If we can deftly combine the extremely low maintenance costs and more or less self-sustaining nature of a good permaculture design with the visual appeal of traditional, high-maintenance and expensive landscaping, commercial and residential owners will be eager to get on board with it.

And the California drought is, for xericulture (sp?) an opportunity. Very good point on the social engineering involved; I am lucky in my situation. But then my town is gardening-mad — though not in public space, which we are rapidly paving over!

On beauty, try Michael Pollan’s Botany of Desire….

In addition to permaculture, I also studied commercial landscaping here in Florida. Xeriscape is already outdated as far as the cutting edge for commercial landscaping goes. “Right plant, right place” is now being advocated in schools. There is some emphasis on low maintenance costs and sustainability for commercial designs, likely because that is what the clients are now demanding.

That said, right plant right place is still a far cry from permaculture, and has only the most rudimentary leanings towards true sustainability. There is still an intense aversion to actual functionality in right plant right place designs.

Doesn’t ongoing permaculture require constant and steady attention by someone or someones with a personal emotional AND material vested interest in the ongoing viability and success of the permaculture? And since any commercial property manager regards landscaping as a pure cost center, wouldn’t they want a “right plant right place” scheme to be as low maintainance and low-observation-needed as possible, since every bit of observation and maintainance would need to be paid for?

The only way I can see commercial property owners and/or managers permitting a high-guidance permaculture on their property is if their employees all feel food-poor and food-insecure enough that those employees would selfishly maintain a permaculture on the premises for their own selfish food-security benefit if they were given managerial permission to do so. It could be considered a fringe benefit of working there ( or living there if we are talking about an apartment complex). But it won’t happen until people feel poor and insecure enough to do it.

Or am I wrong?

You can write into the HOA (home owner’s association) bylaws that a percentage of the monthly dues pay for a permaculture edible landscaper/farmer, rather than just an ornamental landscaper. That way it is well cared for and the bounty belongs equally to all members of the HOA. It then becomes a maturing perennial food (medicine, crafts material, pollinator pathway, wildlife habitat, fragrant, beautiful, etc.) with cycles of harvest and management rather than simply maintenance with no yields.

This is encouraging news.

Cool article. I often wonder why community gardens don’t plant more trees and shrubs? It makes sense to plant things that can come back year after year. My teen years were spent in Florida and one of my happier memories was of a tangerine tree in our backyard.

I’m in the process of trying to find some fruit trees for our new backyard(I’m hoping to have the trees also provide some privacy since we also have 2 duplexes with back porches behind us.) It’s not been easy since the local nursery doesn’t carry them and the nearest farm says they usually get their stock in spring instead of fall.

Readers, do any of you participate in community gardens, and can you say?

My guesses:

1) The ethos is annuals to produce vegetables, not perenniels to produce food;

2) Trees could block sun;

3) The nature of the community gardens as a collection of private plots militates against treating the entire garden as a common pool resource.

There are many permaculturish community forest gardens in the Tampa Bay area. One fairly successful effort has been getting churches to turn their often expansive lawns into such gardens. The plots are not subdivided as such. Also, moringa oleifera grows like a pestilential weed here–and considering the density of nutrients and calories it produces on sub-marginal soil, it’s a staple (tree) crop of the gardens.

I once did, years ago. The Rules included getting everything outta there by Oct. 15th so that the Big Plow Tractor Guy could come in and plow everything down. It went without saying that anything perennial was ruled out. But it also made year-to-year soil-management with soil-building annuals pretty impossible too.

Excellent Lambert, thanks, i’ll have to go by the beacon food forest. I thought it would be an article about foraging and I hadn’t heard about this.Seems like a good way to overcome the seasonality of mushrooms and blackberries. Speaking of which next year should be great for morels because eastern washington is afire.

If you take any photos, please send them along!

Interesting point on fires and morels. We had a post on complex systems recently….

will do, hopefully can get there this week, checked it on google earth and it looks to be in the early stages which could be interesting to others planning such a thing

incredible ideas here. thanks, lambert, for your garden passion.

but what about the deer? deer eat everything they can reach. they’ll chomp new trees down to stubble. here in italy, i watched them arrive and in less than five years change a forest, with all of its creature and bird harboring undergrowth, into campo (grasses and ferns) with tall trees (mainly chestnut and oak where i live).

all vineyards now have to have fences. until recently fences were against the law.

On deer, the pests:

1) I’m blessed in that my area is not infested with them;

2) I use black fishing line on the periphery, dried blood (nitrogen) on the plants round the periphery, distractions like clover on the periphery, and shiny foil tape that blows in the breeze (deer don’t see well). YMMV; “What to do about deer?” is indeed a permathread;

3) Predators.

On the ideas: Yes, I’m saying, perhaps overly subtly, that edible forests should be a high priority for all public land, and that lots of food should be given away for free. Would be a great local project for a Jobs Guarantee, come to think of it. As we keep saying, it’s not like there isn’t work to be done. And edible forests are the essence of “shovel ready.”

I have read somewhere that in preConquest times many Indian Nations would use periodic fires to keep huge areas of land in a mid-successional stage with ever-abundant supplies of browse and mast for deer, turkeys, etc. They would then hunt a sustainable number of deer each year for their meat needs.

If Suburbistan has become a huge zone of Deer Gardens, then perhaps Suburbistanis should do the “indian” thing and begin systematic sustainable killing of percents of the deer herd each year and processing and sharing-out of the meat.

The post here was unexpectedly insightful. Thanks.

Just to add, I view the traditional lawn as not only an eyesore, but also as an scam perpetrated on our society. It is the ultimate expression of our reductive neoliberal economic system. (Our economic system is reductive because the product we create from extracted energy and natural resources is less than the sum of its parts).

A lawns’ high-cost and continuous maintenance requirements should be looked at in terms of rents, not just in terms of money, but also in terms of labor hours, resource consumption, ecological burden, and opportunity cost. Considering the ungodly maintenance requirement of a lawn, it’s no wonder that there is a whole ecosystem of parasitically destructive industries bent on promoting and supplying lawn care. Fighting them off will be/is as difficult as fighting the prison industry, for the same reasons.

I used to live in Port Townsend Washington, a town of small lots and a combination of modest workers houses and grand Victorians that was actually larger than Seattle at the turn of the century. There it is rare to see a front yard with manicured grass— much more common for it to be fenced off to keep the deer out and thus support a maze of vegetables, fruit trees, and flowers.

So what I suggest is a Grass Tax. Not only should it be legal to make productive use of your little “farmstead”, but those who choose to create eyesores and slaughter the Bluegrass on a weekly basis should pay for the privilege. As a revenue-neutral tax, the proceeds could go to purchasing plots for community gardens or community-owned aquaphonic farms.

Every site has its own problems. Squirrels, and occasionally possums and raccoons, do as much damage in urban areas as deer do in more rural ones. They will eat everything and there can be hundreds within foraging range of a garden. One must employ many techniques to discourage them especially since squirrels climb so well and can jump so far and so high.

Several replies have mentioned edible mushrooms. They’re can be difficult to establish and compete with the non-edible fungi in the soil. I do inoculate logs, but have had limited luck with stropharia and elm oysters on the garden floor.

mushrooms are so condition specific it’s hard to move them into your garden, best case they’re there and you don’t disturb the conditions. #1 rule is use a knife to cut the stems so as to leave the mycelial mat intact for next year. For those with a dark basement there are some who successfully cultivate fungi using a pressure cooker and the desired compost mix.

I wonder if having coyotes around and/or letting dogs out at night might scare and pressure the raccoons, oposssums, squirels, etc into reducing their plant predation. Rabbits and groundhogs can also be a problem.

I have a little back yardlet gardenette next to a big brushy woods and I have had zero problems from rabbits, possums, racoons, My beds are raised a foot or more high and I have heard that rabbits can’t figure out to jump up to the bed. I throw urine around to simulate the smell of a big territorial animal which may keep out skunks, opossums, racoons. I had a bad problem with squirrels for a couple of years up in my corn plants till I discovered by accident that squirrels prefer sunflowers to corn. So sunflowers make a good squirrel decoy plant for me. And we do have coyotes living in the area. And many people let their cats run around all day and all night. So maybe that combination can work in other places.

I don’t know what would stop a determined groundhog though, other than a deep enough high enough smooth sided wall. And an even taller wall for deer.

Deer are an excellent source of protein.

i should add that we now (after losing many trees to deer) have an electric fence–four wires–and almost every plant mentioned above: many types of fruit trees, fruit bushes, the lower layers, vines, etc., but it’s not a forest, more like an orchard.

re categorization: walnuts and chestnuts, which we have, are towering trees next to apple, pear etc.

hazelnuts (abundant here) are taller than fruit trees. our mulberry, probably 150 years old–from when farmers planted them for silk worm food, is huge, dwarfing any pear or peach.

the orto (veg garden) has to be a space apart, having traditional fencing that starts underground and rises to six feet to keep out both the stray deer or boar that gets in and the enormous african porcupine whose spines protect it from the electric wire outer fence. this last pest loves roots and vines and fruit and has pretty much eliminated most of the wild iris, symbol of florence, once grown abundantly for perfume. thus, one cant plant, say, fava beans below the olives as they used to do to nourish the soil. one of them just ate chunks out of my prize zucca that was leaning against the orto fence.

i would say that city gardens have it easy, but then we dont have two-legged thieves.

It would be interesting to see a discussion of free-rider principles and the “tragedy of the commons” in the context of edible forest.

The “Tragedy of the Commons” is a neo-liberal “Just So” story. See discussion from Elinor Ostrom here.

I wouldn’t dismiss it outright. Game theory is fairly robust and such systems are always subject to cheaters. Cheaters hoarding more than they need, perhaps for themselves or for sale elsewhere. It’s good around a nice community where everyone knows each other well and, hopefully, likes each other (or at least respects each other) but there are always cheaters around.

Beyond that, my wife and I have decided to allow part of our largest pasture to “go wild” (no more mowing and spraying for weeds). The grass and shrubs and wild plants (“weeds”) will be allowed to grow but with some weedwacker control of the most annoying and troublesome weeds. We want to encourage bees, spiders, snakes, deer, quail, meadowlarks, field mice, voles, ground squirrels to move in. I think I’ll also make use of your info to make additions to our fruit trees. The deer and other creatures pretty much leave them alone – but not the insects. THEY are the bane. Most of the apples are uneatable due to bugs (though my horses don’t mind). The birds consume most of my cherries, and bugs really REALLY love my nectarines. Nothing seems to bother with pears, though but the pear trees like to commit suicide by grossly overproducing fruit to the point of breaking or badly bending their branches. Any ideas on that? There’s too many to prune them away and the tree is too tall for me to do that for the upper half anyway.

This is a common occurrence in many fruit trees (of all types), with several causes. The managed orchards “rub off”, selectively, Spring buds to produce a balanced location and quantity of full growth fruit. This is one reason many fruit trees are “pollarded” to a maintainable height/shape; workability.

While I agree with Lambert that agriculture and horticulture are different, making fruit trees consistently productive requires real knowledge and real work.

I have seen proper pruning make an immense different to yield and “tree happiness.”

I sent you a couple pics of smaller fruit trees (potted).

Small is better and more productive. Espalier fruit trees on walls or wire ultimately is really the way to go if you want an efficient footprint of productive fruit trees IMO. they don’t need to be more than ~4ft tall.

http://www.starkbros.com/growing-guide/article/what-are-espalier-fruit-trees/

I’d progressively prune them back for several years…They’ll be happy.

Thanks for the great post.

Reminds me of communal luxury. We shouldn’t subjugate food production and allocation to the logic of the market when smart common resource management like permacultures does it better.

Nice, but no mention of cultivation/encouragement of edible fungi?

Re. the pestilence that are deer (and rabbits, and wild turkeys, and…) in absence of non-human apex predators, well there’s a fairly obvious remedy there which addresses the proteinaceous part of the edible forest. I’m sure ‘humanity for 95% of its existence’ made quite a lot of use of that ‘crop’. If you’re going to plant low-level crops which are ‘wildlife-attractant’ – as in ‘food for wildlife’, as in ‘helping to boost populations of said wildlife’ – then either don’t complain about the resulting ‘pests’, or take steps to keep their population in check, assuming your local laws allow making use of that aspect of the edible ecosystem. Both venison and rabbit taste great with mushrooms, and with a little extra cooking time a wild turkey would make a great replacement for a farm-raised one in your next holiday feast.

[Cue “not a fun guy” joke here]. Essentially, because it didn’t come up in the stories I read, although the mycelial mat is implicit in the “the root layer.” What additions would you make to take that into account?

Re. ‘friends call me a fun guy and other lonely-hearts sales pitches’ –

Essentially, whenever feasible – i.e. without removal/displacement of specialized other-plant-species-associated nonedibles for which there is no edible substitute filling the same ecological niche – tilt the mix of natural fungi towards the edible varieties. This can involve any of the following aspects:

[1] Managing the mix of tree, shrub and groundcover plants as well as of light and shade;

[2] Selective planting and harvesting of suitable edibles;

[3] Seeking out natural ‘gardens’ of edible fungi and making sure they are harvested sustainably.

I did a quick search for ‘forest cultivation edible fungi’ [” only to set off keywords from surrounding text], and quickly turned up a bunch of interesting-sounding sources along those lines, like the USDA article Commercially-Harvested Edible Forest Mushrooms: Productivity and Sustainable Harvest Research in the Pacific Northwest. I will read deeper over the next few days and fwd links to you as I come across them, and hopefully other readers will pitch in as well.

I wouldn’t mind some fungus photos, either. Readers, see my contact form. (I have a very vivid picture of one in my mind, and can’t bring it to the surface of my Inbox, if if anybody sent me a fungus picture long ago, and it never appeared, please feel free to send it again.)

I’ve had a good experience starting shiitakes on oak logs here in Maine. It takes 2 years under cover in a damp place, with occasional watering during dry spells, to get the mycelium spread through the log and then you get the mushrooms growing by soaking or heavy watering, which you can do every 6 weeks or so with any given log. You can buy a 1000 wooden dowels ready with spawn to plug into your logs for about $50 from Fungi Perfecti, enough to treat about 20 6″ x 4′ logs. If you keep up with them you can have a few pounds a week year round for a few years until they’re done.

I’m assuming a shady area would be best?

Very much so. I should have said damp, dark place. Covering the logs with burlap helps, supported to avoid direct contact.

Thanks, Lambert. My life is an instance of bad timing with regard to this stuff. A year ago this summer my wife and I sold our home of 35 years on a site that would have been ideal for a forest garden. It was already a forest on about a 3/4 or an acre of a south-facing hillside, with a dozen plus oaks of varying ages plus numerous ashes, elms and “lesser” tree species such as aspen when we bought the site, and it had an extensive understory of buckthorn. The man whose family was the third one to occupy the home immediately to our west cut down the forest that had grown on the steep part of the hill in his back yard and then began suggested I do the same to get rid of the aggressively invasive invasive buckthorn. He was not amused when I pointed out that he had just planted a monoculture of an invasive species called grass, and that he and I were members of the most invasive species ever to roam the Earth. My wife wanted to retain the privacy afforded by the dense understory and I never found an alternative with which I could replace the buckthorn at reasonable cost, although I must admit I didn’t look very hard. However I did have many enjoyable moments watching my neighbor trying to negotiate the 20+% grade of his back yard hill with his lawn mower.

I followed many of the links in your piece and I believe my former property would have been ideal for Hugel Kultur mounds. One issue with the buckthorn is what do you do with it when you’ve cut it down. It would have been ideal for the base of the mounds, especially when combined with the oak and elm wood from the several trees had died and had to be cut down over the years. Over time what I planted on the hillocks would have developed to provide the same growing-season opacity that the buckthorn did.

Maybe you could find a local project?

Not much by way of an edible forest on my property in Chicago. The old country is where I have a very nice foundation for an edible forest, no thanks to me. My grandparents have about 50 fruit and nut trees on their 3/4 acre homestead, in addition to many of the other elements mentioned in the article. So the walnut is slowly dying, it’s well over a hundred years old. It’s sad to see this old friend go, I used to spend a lot of time under its shade as a kid. I will use the lumber to build furniture, and the successor is already planted and growing well. One thing that had never occurred to my grandparents (or to me) is to plant an oak or two, the acorns would make for a nice flower. The missus had the smarts to present me with ‘Oak: The Frame of Civilization’ for my last birthday, so this fall I will plant several oaks when I go back. Highly recommend the book BTW, it’s extremely educational without ever feeling like a textbook.

Interesting article if a little little hippy trippy. Looking at the US there appears some potential for edible forests – but elsewhere?! Here is an illustration that its not always so simple.

Dont get me wrong. We have thanks to a friend a conceptual permaculture scheme for our own 6 acres down here in Oz and are going through the tree hugging dream – (massively subsidized by the fossil fuel needed to get there). And our land is as well drained and has good timber as it comes. But the idea of an edible forest is a bit far fetched to believe it would work for us on many counts of which the following are a few:

– Even in wet areas of Oz the dominant forest plants are not that great at providing edibles unless you are a koala, a termite or a witchetty grub. Eucalypts are great for firewood and building material but they arent much use to humans as food directly.

– The understory they support/ need is not edible either. But if you dont have the natural stuff then you have to deal with weeds – blackberries and rasberries are maybe ok in the US but for us they are noxious weeds which crowd out natural habitat and encroach on natural bush.

– Eucalypts love fire so unless you are in rainforest areas, your understory is likely to be decimated reasonably frequently.

– And our forests harbour that most feared of creatures – The Possum – not those rat like Opossums you have, but the evil superadaptable Brush Tail who will eat all your veg and then sit on branch chitting (laughing) at you – we may not have kangaroos in the middle of Sydney but we sure as hell have possums – even despite the cats and foxes. Ask a NZ Kiwi about these blighters and what they have done there – they are NZ’s Cane Toad. If you try and grow anything edible for humans or even not edible these blighters will grab the berries long before you can.

– There are other ferocious marauders around our farm too – native Ratus that dig tunnels to the peanuts, flying foxes, antechynus…and I havent even started talking about bugs of all kinds that find fruit tree leaves delish.

So much for human competitors. Now a bit of nutrient balance. Like in economics forest nutrients cant be extracted forever at no cost. Sadly many permaculture people dont understand this or just how large human nutritional needs are.

A separate issue when you practice permaculture is nutrient drainage. Permaculture promotes rich soil – unfortunately the nitrogen kills off local species so the two are incompatible.

And while I’m on this, ‘natural’ nitrogen isnt so great either – if you grow lots of nitrogen fixer containing legumes you will slowly acidfy the soil as surely as acid rain unless you get into mining dolomite etc.

Returning to ferals, the other day we planted a bunch of fruit trees including Guava and Locut. Now we find these are like Blackberries – on the to be destroyed list.

In conclusion I am all for replacing modern Agribusiness with some system that is much more ecologically sustainable but this will not be cheap and easy and the solutions will vary greatly by locations, and may not work if you try and mix horticulture at least as judged by production of edible non boring foodstuffs rather than our friend’s pumpkins.

Eucalypts do not love fire. They have the capability to withstand fire (if mature) and regenerate after fire (sprouting behavior). But as a thin, loosely barked tree that creates a “trashy” forest floor, eucalypts create dangerous fire conditions. (See: Oakland Hills Fire.)

Eucalypts were brought to the US from Australia as hopeful substitute pier pilings and a quick growing wood lot. They’ve proved to be neither. They were thought to be a potential thirsty tree to drain wet areas (bayous?), but that’s debatable, as well. Eucalypts are an invasive tree species that would have been best left in Australia.

They were brought here by someone who called himself a “Professor” of biology, but looked more like a snake oil salesman.

Surely the Aboriginal Nations knew / may still know what indigenous edible fruits/nuts/etc grow on what plants? And what do all the parrots eat? Some parrot-edible plant parts may be human edible as well. An Australian permaculture could surely make some use of Australian food-bearing plant species.

Such willful stupidity, and from someone who is otherwise so intelligent and skeptical.

This is all great – BUT ONLY AT A LOW POPULATION DENSITY. It cannot work if we jam billions of third-world refugees into a country the size of the United States. Cannot.

You are so utterly brainwashed by ‘the more the merrier we need more people to grow the economy without $2/hour labor the crops will all rot and we will all starve anyone who thinks that turning the United States into another Bangladesh is bad must be scapegoating immigrants’ propaganda that you simply cannot accept that THIS WILL NOT WORK WITH HIGH POPULATION DENSITIES.

“Edible forests?’ Look at India. The place had been turned into a human feedlot, the land stripped bare and the rivers run with filth. How are people to survive on ‘edible forests’ in a place like India? When there are no forests left?

If the concept of “food forest” were expanded to include “food savannah”, then there might be found a rising number of food savannahs in the upper Midwest. Mark Shepard has been developing and refining the concept on his Wisconsin property.

http://www.resilience.org/stories/2010-11-12/mark-shepherds-106-acre-permaculture-farm-viola-wisconsin

There are lots of google entries for Mark Shepard permaculture.

Learning how and why plants pattern themselves in nature and about the effects of the diverse kinds of diversity on ecosystem function can add great richness to the tool box of the forest gardener. The unique inherent needs, yields, physical characteristics, behaviors, and adaptive strategies of an organism govern its interactions with its neighbors and its nonliving environment.