By Perry Mehrling, a professor of economics at Barnard College. Originally published at his website.

The Office of Financial Research is out with a new “Reference Guide to U.S. Repo and Securities Lending Markets” which collects together in one place most of what is known, and draws some attention to how much is not known, about this key bit of monetary infrastructure.

Kudos to the authors for treating repo and securities lending in the same document, since in practice they do much the same thing. Repo is structured as a simultaneous purchase and forward sale of a security: on the first leg cash goes one way and securities go the other, while on the second leg the flows are reversed. Securities lending against cash collateral involves much the same pattern of flows, and thus offers an alternative way of doing the same thing.

To be sure, the securities involved are typically different: repo involves Treasuries and government agency fixed income securities whereas securities lending often involves equity. And a good chunk of securities lending is against security, not cash, collateral. But that just means that, from a money view perspective, repo is the core activity and securities lending the periphery. In order to understand the system as a whole we need to understand both, and how they interact.

What we know about the system mostly comes from the reporting of the primary dealers who do regular business with the Fed, reporting that arises originally from the Fed’s concern for ensuring liquidity in the Treasury debt market. We also now know a lot about the tri-party repo market, as a consequence of its role in the financial crisis.

What we do not know much about is the bilateral repo market, and anything involving non-primary dealers. In particular, though the report only hints at this, we don’t know much about the offshore repo market. Presumably the OFR is relying on the work of analogous financial research bodies in London, which will then have to be integrated in order to get a picture of the entire system. For now, however, it remains a black box.

What we know is that the repo and securities lending we can see has shrunk a lot since the crisis, in significant part because of new regulations that make it a less profitable business. What we don’t know is whether the repo and securities lending we cannot see has also shrunk, or maybe has taken up some of the slack.

One important thing I long assumed to be true is confirmed by the report. The repo haircut, which is the difference between the market value of the security and the size of the cash loan, is NOT appropriately understood as compensation for credit risk. Here is the key passage:

“The events of the 2007-09 financial crisis revealed that cash investors, especially those whose decision-making is tied to corporate governance procedures, do not dynamically adjust haircuts when counterparty credit risk rises, but rather request higher quality collateral or limit their repo investment activities to higher quality counterparties.” (p. 42)

What this means is that when the system is in expansion mode the list of eligible collateral and eligible counterparties expands, and when it is in contraction mode the list of eligible collateral and eligible counterparties shrinks. Credit quantities, not credit prices, absorb the system-level fluctuation, which is easy enough in expansion mode, but a very different matter in contraction mode.

The report emphasizes the danger of fire sale in the contraction, i.e. price volatility. The idea seems to be that the shunned counterparties will be forced to sell the shunned collateral, for whatever price induces some other holder of cash reserves to buy. In this way the fleeing cash investors get the cash they want, at the expense of the shunned counterparty and to the benefit of some other cash holder who jumps into the fray to get a bargain. Maybe, but also maybe not.

From a money view perspective, the problem is rather one of refinance. When one class of cash investors turn away from a category of collateral or counterparty, it is unlikely that another class of cash investor will be willing to part with their own cash hoard, accumulated against exactly this moment. What is needed at such a moment is a source of additional cash, an entity issuing its own cash liabilities and using the proceeds either to lend to the shunned counterparty or to acquire the shunned collateral. Credit quantities, not prices, are the answer, and that depends in the first place on a robust lender/dealer of first resort system.

According to the report, one idea about how to avoid fire sales is to eliminate the current exemption from the automatic stay in bankruptcy that currently allows repo creditors to grab the security collateral and sell it. (Remember, repo is constructed as a paired security purchase and sale, so after the first leg the cash investors actually own the securities.) But so far as I can see, probably that would be the end of repo. (See an earlier related post here.)

What cash investors want is cash, not securities, even securities that they can sell in the event their counterparty fails to deliver promised cash on the second leg of the repo. I am reminded of a well-known bit of market wisdom I first heard from Richard Comotto. “Sometimes it is good business to accept dodgy collateral from a good counterparty; it is never good business to accept even first-class collateral from a dodgy counterparty.” Cash investors do not want to be secured creditors, even if that puts them at the front of the line in bankruptcy proceedings. They want cash. If repo is just secured credit, not cash, they won’t invest in the first place.

So maybe we can do without the repo market?

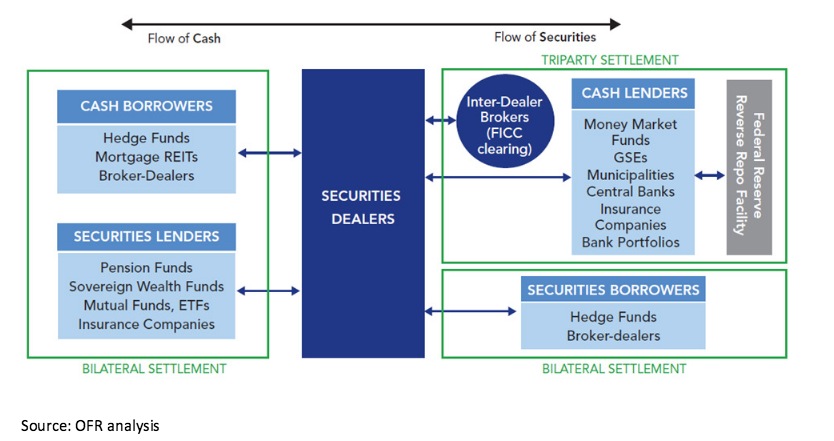

The great contribution of this report is to make abundantly clear how crucial a functioning repo market is to the larger financial system. For my money, the most important figure is Figure 7, which shows schematically the balance sheet of the dealer system:

The hierarchical character of the system is clear in this figure. Security dealers borrow cash from cash lenders of various kinds, who insist on channelling that cash through the tri-party repo system because of the extra security it offers them. And security dealers lend cash to cash borrowers of various kinds, using the bilateral repo system because of the extra flexibility to repledge the securities that they acquire. Cash flows through dealers in one direction, and collateral flows through them in the other direction.

And that brings us to the main point. The primary dealers are the core of the lender/dealer system of first resort that we have relied on in the past to absorb liquidity shocks of various kinds. If cash investors shun particular collateral or particular counterparties, dealers take over that business (for a price), expanding their own balance sheets on both sides. If dealer liabilities, maybe even repo liabilities, are acceptable to cash investors, then we are done. No fire sale, just refinance.

Of course this is the system that failed during the financial crisis, leading to reliance instead on the Fed as lender/dealer of last resort. The question on everyone’s mind is whether the institutional changes since the crisis, some of them in response to regulation, have delivered a more robust dealer system, or a more fragile one. The bit of the system we see is better capitalized, but is it able to provide the elasticity we need when we need it? Or will we be depending on the bit of the system we cannot see, whose resilience we have no ability to evaluate.

The statistical net focuses on primary dealers, because of their role in ensuring the market liquidity of government debt in an immediate post-war era when management of government war debt was the main challenge. What we need today is a statistical net that rather focuses on the dealer function, on whatever balance sheet it may be found, whether officially designated primary dealer or not, whether domestic or international. We have learned the hard way that ensuring the market liquidity of government debt is not sufficient to ensure financial stability. We are still trying to figure out how to create a robust dealer system for the modern financial system.

So this points to the failure of the primary dealers to respond in a systemically stable manner at the outset of the GFC, requiring the FED to step in, then asking if next time will be different based on new regulations and the unquantifiable impact of shadow influences? Am I reading this correctly? If so I’d have to say I think we’re lucky the FED has an unlimited balance sheet…

And that brings us to the main point. The primary dealers are the core of the lender/dealer system of first resort that we have relied on in the past to absorb liquidity shocks of various kinds. If cash investors shun particular collateral or particular counterparties, dealers take over that business (for a price), expanding their own balance sheets on both sides. If dealer liabilities, maybe even repo liabilities, are acceptable to cash investors, then we are done. No fire sale, just refinance.”

Of course this is the system that failed during the financial crisis, leading to reliance instead on the Fed as lender/dealer of last resort.

What I don’t understand that in an era of electronic transactions, why we even have primary dealers. Why can’t any bank that passes pre defined criteria of soundness and probity be used as a conduit for this function?

Because of

“Sometimes it is good business to accept dodgy collateral from a good counterparty; it is never good business to accept even first-class collateral from a dodgy counterparty.”

Its still a subjet subject system. Trying to turn this into a computerized system would invite

a] possible gaming – no human evaluation

b] sub-optimal resource due to non-adaptive algorithms and models [i.e. brittleness]

On the other hand its quite a problem because these structures are pre-computer and cannot possibly cope with the required liquidity, transaction volumes (frequecies), clearing and settling required to have the financial system work under extreme stress.

And its not just repo’s – just think of the actual processing chains involved in unravelling complex products.

The whole thing needs to be redesigned.

I don’t follow this much. Today’s NYT did a piece on the Fed’s plan to “use old jargon” to facilitate new liquidity mechanics that have little to do with the overnight rate but rather serve to maintain liquidity by “paying lenders not to lend”. I don’t understand a word of it. Someone please translate what this means in terms of the economy and financial stability.

I too don’t understand these mechanisms. I particularly question what is occurring in the global financial system behind a cloak of complexity and information obfuscation.

Besides being a mechanism to influence interest rate policy adjustments, is the Fed’s Repo and Reverse Repo facility not also a vehicle for the Fed to inject cash into the financial system through “approved counterparties” to address financial panic and illiquidity? Is information on amounts outstanding under these facilities, types of collateral accepted, and with whom transactions are being done by the Fed publicly available on a timely basis? I think not.

Is the default an assumption of “safety and soundness”, including WRT offshore financial intermediaries? What are the metrics being used in these assessments?

If we are to indirectly underwrite the participants in the system, as we citizens have done and are doing through forced acceptance of negative real interest rates, then we are entitled to know and understand exactly what is occurring, and the magnitude and nature of the risks.

The new stuff the Fed set up to unwind QE is straight forward enough. Back at the beginning of QE 1 they had to assure the bond market that the Fed had a way to unwind QE that didn’t involve dumping a trillion$ of long term bonds on the market. That coulda spooked the bond market(and Chinese, Japs, etc..) and the result is long rates go up, the opposite of the then Fed goal. So repo was a way to not dump Fed inventory of long term bonds and instead pay short term rates for money and hoover up liquidity – the Fed bond inventory serving as the collateral part.

They also knew they couldn’t control rates the traditional FOMC transaction way, selling short term treasuries to tighten money (1 trillion of it then, 4 trillion now), because the Fed inventory would be mostly in long term treasuries, rather than short term bills that sell near face value. [If the Fed tried to sell lots of long term bonds – they would “lose money”] So that was another reason for repo, and also used to justify the part about paying interest on bank reserves. That sounds a bit fishy to me, because I think once you have the repo facility, that shoulda been sufficient, I would think.

Then they were concerned that with the high volume of repo possible, they may overwhelm the capacity of traditional primary dealers (19 of them). So they decided to open it up to money markets as well.

I think this is where it gets interesting. If they are offering money market funds a safer way to make interest than tri-party repo I think it’s a good idea and money market funds seem to be very interested.

But if this is a back door way of providing a Fed backstop to triparty repo in general then I think it’s a bad idea. This would seem like another bailout rather than letting the markets clear.

I don’t think this is about safer interest for money markets. What we are talking about is the liquidity plumbing underlying financial market dynanics with the Fed acting as cash lender of last resort.

If repo’s and stock borrow and loan were abolished, a lot of trading would simply stop because these firms couldn’t fund their daily operations [they would immediately have severe liquidity problems]. This is because trading and deal making runs at a much higher frequency than clearing and settlement – its embedded and that allows funding elasticity during they day.

The Fed could do a lot to stop speculation if it closed these funding windows and stopped guaranteeing speculation.

Thanks. As Geoffrey Ingham has pointed out ‘all money is credit but not all credit is money’. I don’t think we want the Fed turning all of this bizarre type of credit into money good.

As you said earlier I think ‘the whole thing needs to be redesigned’.

We seem to need the Fed to close funding windows for speculation and open them for the many useful things that could benefit society.

What would you see as some ideas that could drive this sort of investment?

I think a good start is to read Michael Hudson’s book “Killing The Host” and Karl Polyani’s “The Great Transformation”, Once it becomes abundantly clear that markets and finance are a subset of society and should not drive decisions which actually live in the moral, survival and philisophical dimensions, perhaps we can turn to investing in real productive capacities, pay attention to real social justice and start inventing a better future.

William Lazoncik also has done some great analysis about what he calls the Theory of the Innovative Enterprise and deals with how enterprises should be organized, what is their purpose, etc.Smart stuff.

One of the first steps is to get this crazy and monstrous neoliberal market and finance system under control before it kills all of us and the planet to boot.

Democracy and unregulated markets are an evil and toxic mix when it lurches this far toward the current toy economic market theory, which is simply used to justify privilege and power.

It should be clear that decisions are not made by the citizens, but by the 0.1 percent – that has to be the first thing thats fixed.

Sometimes obscurity is intentional, to cover up fraud – as in all those derivatives hardly anyone actually understood. (At this point ,it seems a good question whether even the people who created them understood; at least, they hadn’t thought through the implications.)

One issue is since 2007 when the Fed started paying interest on excess reserves thereby reducing the opportunity cost to hold reserves at the Fed, Fed Reserves have now become the ultimate true risk free asset even more than Treasury Bills. In Europe where corporates such as Siemens and Airbus can form their own in house banking subsidiaries with direct access to the ECB this is even more true.

In the US direct access to the Fed is more difficult but it is possible to deposit with custodian banks such as State Street, BNY, Northern Trust on the basis they are “safer” and not dependent on primary dealers to sell to on the Treasury market.

When will someone pay me some interest in my deposits/reserves? What do you bet that even if rates go up there will be no increase in interest paid on savings accounts, CDs and the like. Twelfth of Never, I’m thinking.

Perry Mehrling does not understand what dealers do. The bizarre framing that “Credit quantities, not credit prices, absorb the system-level fluctuation” is simply evidence of this. Newsflash: when the “list of eligible collateral shrinks,” the market ends up moving along the supply curves for eligible and ineligible collateral and both price and quantity will change: Price of eligible collateral will skyrocket, price of ineligible collateral will plummet; yields will move in opposite directions.

As Matt Levine explained here:

“But the dealer’s function is really about smoothing trading across time, not about preventing price moves. If someone is selling now, the dealer will buy, and if someone is buying in five minutes, the dealer will sell, and most of the time that is a reasonable, volatility-dampening business model. But if everyone is selling for days, it would be dumb for the dealer to keep buying all the way down. That is just not the function of a dealer: Dealers are the buyers and sellers of first resort, not of last resort, and their function is not to take huge contrarian risks on long-term fundamental positions. They’re in the moving business, not the storage business, as the cliché goes. The actual buyers or sellers of last resort — the people who buy when everyone else is selling, or sell when everyone else is buying — are longer-term value investors. The dealer intermediates in time between fundamental buyers and fundamental sellers, but you need the fundamental investors for the system to be healthy. ”

The business model of the dealers includes a very simple rule: If you NEED to sell to a dealer, you will get screwed. Repo and margin contracts have been designed to guarantee this since the day they were first drafted.

I think that is not from Mehrling per se, but p. 42 of the reference guide by the Office of Financial Research.

Perhaps, the key phrase is the part that cash investors do not ‘dynamically adjust haircuts.’ Maybe they do, but not fast enough (dynamically enough)?

The bilateral repo seems to operate like a margin account. If I own a thousand shares of IBM, I can give these directly to a brokerage, ie MF Global, as collateral for cash. If they go down in value MF Global will demand some cash back in a type of margin call.

But say they have repledged, rehypothecated, these securities. They borrowed cash from an innocent money market fund looking to generate a tad of interest and gave these thousand shares of IBM as collateral. Here is where the third party comes in. JP Morgan holds both the cash and the securities. If things go bad, either with the securities they hold or with what MF Global decided to do with its new cash, they hold onto the cash, ie don’t unwind the repo. Innocent money market fund loses money and breaks the buck. Public panics and takes money out of money market funds. JP Morgan returns devalued shares to MF Global. MF Global unable to borrow any more from money market funds.

What should the Fed role be to fix this? I don’t think there should be ‘innocent’ players here. Give savers who want it a Fed fund rate. For investors who want to be active in the repo system give them appropriate interest for the counterparty risk and then let them suffer the consequences or reap the benefits.

What is the tri-party repo system referred to in the article?

From the article: ” A triparty repo involves a third party, which is a clearing bank. The clearing bank provides back-office support to both parties in the trade, by settling the repo on its books and ensuring that the details of the repo agreement are met. In the U.S., triparty repo services are currently offered by Bank of New York Mellon Corp. (BNY Mellon) and JPMorgan Chase & Co. (JPMorgan), both of which provide clearing and settlement services to securities dealers.”

—————-

“Unwinds are at the discretion of the clearing bank. This significant fact was not well understood by some market participants prior to the financial crisis.”

http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/epr/2012/1210cope.html

Thanks.

“What should the Fed role be to fix this? I don’t think there should be ‘innocent’ players here. Give savers who want it a Fed fund rate. For investors who want to be active in the repo system give them appropriate interest for the counterparty risk and then let them suffer the consequences or reap the benefits.”

But… but there would no way to screw money out of innocent people that way!!!!! Verboten. Nein, nein, nein!

I saw something recently that hints at the “fix” we’ll probably see. Non-government security money market funds will disclose that it’s possible they can “break the buck”. So you can invest in Lehman, Long Term Capital Management, or whatever for your .25% compensation for inflation and counterparty risk.

But you should feel good about how you’re helping out the economy. In lieu of any charitable tax benefit, of course.

there’s always a silver lining if you peel the onion back to the bottom of the pit!

one thing I’ve noticed with these big money types — and i don’t mean Professor Mehrling, I mean the guys who complain about “liquidity” in places like financial newspapers.

What they seem to have a problem with is they can’t foist their junk on somebody at the price they want for it. Well, if i want to buy a pair of Edward Green shoes for $120, brand new from a boutique shoe store, for some reason i can’t. i don’t call that a liqudity problem. I’d call that a sanity problem. And it’s not the shoe stores sanity problem.

Why does this page go down every time I type a keystroke. I’ve never seen that before.

Actually, it’s more like they think their (used) Edward Green shoes are worth $2000, and the Fed needs to provide enough liquidity to consummate the deal. ‘Course the trader next door has used $20000 suits for sale. This is why things can add up to trillions. But the financial press understands these things. They just don’t like repeating the basics over and over again and get straight into the meat of things – interest rates and liquidity.

Dunno. The page stays still on my computer.

Just remembered. There’s all the used kinky stuff from Victoria’s Secret. But that’s held “”off balance sheet” in an offshore account, so we don’t know how many trillions that’s worth.

well. we did without it for 50,000 years since the Cave Painters. if we say “contemporary life” started then we’d have a point.

so 50,000 years without repro.

Vixere fortes ante Agamemnona multi; -Horace

but what great feats does its trampoline permit gymnasts to perform to the amazement and delight of crowds?

that could be a ‘Deep Thoughts” question.A few beers at The Wonkery and you start thinking deep thoughts mixed in with technical mumbo jumbo. After 3 or 4 beers the Deep Thoughts are flowing like pee. After 6 beers it’s all over until tomorrow.

mmmm…beer

damn right

I like that “The Wonkery”

It’s the sort of English pub where you can get drunk and talk about repo and nobody thinks your a foo foo king

They can stil lhave sports on the TV though. Also, please, have some cold crisp American beer. For God’s sake

This also brought to mind the article regarding banks no longer guaranteeing something regarding how they are exposed to derivatives and thus being able to offshore risk into the shadow system but I can’t recall or find the link from a few weeks ago

Three card Monte. Everyone can pretend they have real money because of artificial money created by Fed to buy treasuries issued by government that does not have money and does not want to raise taxes to keep the oligarchs happy.

Two questions, from someone who obviously doesn’t get it:

1) what is the purpose of all this persiflage? Why do they do this when the banks are flush with cash and can go to the discount window and get money for nothing? I don’t understand why these deals are even legal, no less why they engage in them

2) what do the players need with this cash when there are loans, stock issues, corporate paper, and the Fed all available and functioning to provide liquidity to corporations? In a world where credit is very tight, you could just imagine (if not condone) these shenanigans. In a world flush with liquidity, they make no sense.

All liquidity isn’t created equal and this game of extend and pretend seems to be trying to avoid the game of musical chairs where someone doesn’t get a seat.

In his book ‘Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk’ (2011) Satyajit Das talks about the ‘Liquidity Factory’.

On an inverse pyramid at the bottom little pinnacle are the central banks, 2%, then there are bank loans, 19%, then securitized debt, 38% and then derivatives 41%.

This is all considered liquidity, the lubricant that allows the global economy to run. 79% of it is derivatives and securitized debt which are largely unregulated and full of fraud. The $16 trillion of US Treasuries used as collateral to back it all up is a small fraction.

This is financialization run amok and what he calls ‘cotton candy’ which is spun sugar composed mostly of air.

No wonder central banks don’t want us to be able to examine bank balance sheets but just have the taxpayer continue to bail them out while imposing austerity measures.

This mountain of debt being supported by this little pyramid needs to be dismantled before the right grain of sand causes it to crumble.

Some ways we could dismantle this is that countries shouldn’t have to pay back loans that their former dictators stashed away for themselves in off shore accounts. Students shouldn’t be indebted for most of their lives by college loans, medical bills shouldn’t be the major cause of household bankruptcy, homeowner’s who were given predatory loans so that the banks could repossess their house should have principal reductions to reflect actual value.

If US Treasuries continue to support cotton candy they will lose their validity as a global reserve currency.

————–

Scott Fullwiler has a good discussion of Corbynomics which would be another move in the right direction by getting these funds into the bank accounts of people who need it and away from the cotton candy.

The triparty repo market seems to be mainly leveraging these funds into cotton candy.

Thank you. But I still don’t really understand how you need such vast amounts of liquidity when the global GDP is something like 85 trillion dollars. Since even a guy like Milton Friedman argued that there is such a thing as the velocity of money, you shouldn’t even need $85 trillion to grease the skids. What the hell does all that money do? Since no one person is worth more than $80 billion or so, it isn’t in the hands of the uber-rich. What the hell is it doing, and who owns it?

I don’t think it is needed. I think it and the whole process, especially when you get into the securitized debt and derivatives, is wasteful speculation that benefits a few.

They are lumping together liquidity and asset values. Technically incorrect – because it makes people (like you) not understand, because we know there really IS volume of money AND velocity of transactions.

So really, looking at the US, The Fed balance sheet is 4.5 trillion. That is the “liquidity”. In our present economy, it doesn’t all go into the real economy – with whatever our macro “velocity of transactions” in real goods and services is. So you can think of it as going into “greasing the wheels” of asset trading and asset inflation. The asset is not money, remember. Money is just the unit of measure in how the asset is being valued. ‘Course, real goods and services aren’t money either. So we’re all consistent in our thinking now.

Where things get spooky is any kind of made up financial piece of paper is now considered an asset. (ie weird derivatives, dodgy debt, whatever)

Then banks get regulated on capital ratios. Asset bubbles pump up the “good” side of the balance sheet. This in turn allows the bank to take on more liabilities. Which is sometimes called creating “bank money”, or endogenous money creation, or that air money stuff, cotton candy…etc..etc…

Then the feedback loop continues to go ’round and ’round.

I think that’s essentially correct.

Michael Betancourt (http://michaelbetancourt.com/)has a couple of articles that kind of discuss this feature in his usual airy but insightful way. He calls it digital capitalism and what we are seeing is the never ending spiral of “dematerialized value”, which simply means there is no physical reality associated with the products or assets. Its just money flow [demand not value].

Michael Hudson in his latest book “Killing the Host” goes into this topic in some depth when he recounts the latest financial crisis and explains its debt structure.

Ya, it does go a long way in explaining the how, and why, we got the $600 trillion, or whatever they think the number is, in global derivatives.

If electrons had nutritional value, there couldn’t possibly be world hunger.

One of my favorite authors, John Crowley, describes something like this, saying: “The farther in you go, the bigger it gets.”

The Similar Something is, amusingly, Faerie. A parallel world to this reality that’s always just there.

Seems about right.

I’m vague and stupefied, but I think I think this is just highly controlled trickle down. So that the upper economy continues to function (but why even bother?) and the base of the economy is prevented from creating dreaded critical mass, i.e. inflation that can’t be easily controlled. But in terms of economics, a healthy economics, and stability, this all seems to turn old ideas on their head. And thus vast landscapes of inequality and etc. Where can this even go?

It goes BOOM! In a bad way, I mean.