This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 604 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in financial realm. Please join us and participate via our Tip Jar, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our third target, funding our guest bloggers.

Lambert here: Thinking purely politically, this analysis squares a lot of circles.

By Robert Z. Lawrence, Professor of International Trade and Investment, John F Kennedy School of Government Harvard University, Senior Fellow, Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics, and a former member of of the President’s Council of Economic Advisors under President Clinton. Originally published by VoxEU.

The US debate over income inequality in the 1980s and 1990s focused on the growing disparity between the earnings of the skilled, the unskilled and the super-rich. After the global crash, the decline in labour’s share of national income has been added to these concerns. This column presents an alternative explanation for this decline, arguing that limited substitution possibilities between capital and labour combined with the acceleration in the pace of labour-augmenting technical change raises the effective labour-capital ratio. The policy implications of this alternative explanation are profoundly different from those currently circulating.

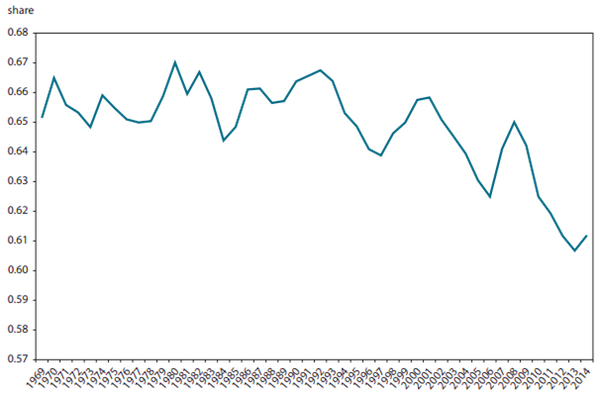

The US debate over income inequality in the 1980s and 1990s focused on the growing disparity between the earnings of skilled and unskilled workers and the earnings of the super-rich. Since 2000 and especially after 2007, however, the decline in labour’s share of national income (See Fig 1) has been added to these concerns.

There are several plausible reasons for this development — globalisation, automation, weak bargaining power of labour, political capture, higher markups — but the natural starting point for explaining factor income shares is the theory of the functional distribution of income enumerated by John Hicks (1963) and Joan Robinson (1932) in the 1930s. This theory, which emphasises the ease with which capital and labour can be substituted, points to a combination of weak investment and technical change that has made workers more productive as the explanation for recent declines in labour’s share in income.

Figure 1. Share of labour compensation in US national income 1969-2014

Source: BEA National Income Accounts Table 1.12.

Capital’s income equals the rate of return on capital (r) times the quantity of capital (K). Similarly, labour’s income equals the wage rate (w) times the amount of labour employed (L). Thus the ratio of factor incomes, (rK / wl), can be expressed as the product of relative factor prices (r/w) and relative factor quantities (K/L).

Relative factor prices (r/w) and relative factor quantities (K/L) will generally move in opposite directions. More expensive capital – a rise in r/w for example – will induce firms to produce with lower capital-labour ratios. Thus the changes in the ratio or shares of income that accrue to capital and labour will depend upon how relative quantities and relative prices change. If two goods are close substitutes, a small change in their relative prices will give rise to large changes in the relative quantities that will be demanded. Similarly, if capital and labour are easily substituted, a large change in the relative supplies of capital and labour will need relatively small changes in their relative prices for demand to adjust:

- If substitution is easy, a given percentage increase in the quantity of capital relative to labour (K/L) will raise capital’s income share because it will be offset by a relatively small percentage decline in capital’s relative price (r/w);

- If substitution is difficult, however, small changes in the relative supplies of capital and labour will give rise to large changes in their relative prices.

In this case, a percentage increase in the quantity of capital relative to labour will be more than offset by the percentage decline in the relative price of capital, and capital’s income share will fall.

The ease with which capital and labour can be substituted can be defined more precisely with a measure known as the elasticity of substitution – depicted by σ. This indicates the percentage change in K/L when r/w changes by 1%. Since relative prices and quantities will move in opposite directions, σ is defined negatively. When σ = 1, relative prices and quantities move in opposite directions by similar percentages and factor income shares are unchanged. However if σ is greater than one, capital’s share will rise when its price falls since the percentage change in the relative capital-labour ratio will exceed the decline the relative price of capital. If σ is less than one, however, capital’s share will fall when its relative price falls since the percentage decline in prices will exceed the percentage increase in the relative supply of capital.

Based on the assumption that substitution possibilities are considerable and σ is greater than one, several leading recent authors have claimed that a rise in the quantity of capital relative to the quantity of labour (capital deepening) is responsible for the decline in labour’s share in US income. This view is reflected in papers by Elsby et al. (2013) and Neiman and Karabarbounis (2014), and most famously in the book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, by Thomas Piketty (2014). The explanations for capital deepening offered by these authors differ, but all three imply that since capital and labour are highly substitutable, the increased relative supply of capital has been met with a less than proportional decline in its relative price. Specifically, Elsby et al. claim the reason is an increase in capital intensity due to the offshoring or more labour intensive production, Neiman and Karabarbounis claim that the declining price of investment goods has raised the capital-labour ratio, and Piketty claims capital deepening has taken place due to a decline in the growth rate in the face of a constant saving rate.

But this line of explanation suffers from two basic flaws. First, it is at odds with the preponderance of studies (see surveys by Chirinko 2008, Rognlie 2014, and Lawrence 2015) that have found that the substitution possibilities between capital and labour are relatively low and σ < 1. In this case capital deepening would actually increase rather than reduce labour’s share.

A second problem is that these explanations ignore the possibility of technical change that makes labour more productive – so-called labour augmenting technical change. This second oversight is also serious, because studies of the direction of technical change have concluded it is net labour augmenting (Antras 2004, Wei 2014, and Young 2010). In the face of powerful labour augmenting technical change, even if the physical ratio of labour to capital might have fallen, therefore, once technical change is taken into account, the effective supply of labour relative to capital might actually have risen.

A New View

Correcting these two flaws provides an alternative line of explanation for the decline in labour’s share:

- Limited substitution possibilities between capital and labour (σ < 1) combined with acceleration in the pace of labour augmenting technical change, which raises the effective labour-capital ratio.

In recent work (Lawrence 2015), I present empirical support for this alternative explanation.

Using regressions that produce estimates of both the elasticity of substitution between capital and labour and the magnitude of capital and labour augmenting technical change, I find that the elasticity of substitution is generally less than one in many US industries as well as the US economy as a whole. The estimates also imply the effective capital-ratio has actually fallen in many industries because the measured rise in the (physical) capital-labour has been more than offset by an acceleration in the pace of labour augmenting technical change.

In combination, these estimates of low substitution elasticities and declines in the effective capital-labour allow me to account for much of the decline in labour’s share in the US sectors and industries (such as manufacturing, mining, and information technology) that are responsible for most of the decline in labour’s share in income.

Important Differences in Policy Implications

The policy implications of this alternative explanation are profoundly different from those advocated by Piketty. Piketty advocates taxing capital. But if σ is < 1, increasing taxes on capital could lead to further reductions in labour’s share! Paradoxically, with σ < 1, policies that increase investment and the supply of capital could achieve more equal distributions of income. Accordingly lower taxes on capital and a progressive consumption tax could be the most effective approach to boosting investment and reducing US income inequality.

References

Antras, P (2004), “Is the US Aggregate Production Function Cobb-Douglas? New Estimates of the Elasticity of Substitution”, B E Journal of Macroeconomics 4(1).

Chirinko, R S (2008), “The Long and Short of It”, Journal of Macroeconomics 30: 671-686.

Elsby, M W L, B Hobjin, and A Sahin (2013), “The Decline of the U.S. Labour Share”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Washington, September.

Hicks, J R (1963), The Theory of Wages 1932, reprinted as 2nd edition, London, UK: MacMillan.

Karabarbounis, L, and B Nieman (2014), “The Global Decline of the Labour Share”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(1): 61–103.

Lawrence, R Z (2015), “Recent Declines in Labour’s Share in US Income: A Neoclassical Account”, NBER Working Paper 21296 and WP 15 – 10, The Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Piketty, T (2014), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

Robinson, J (1932), Economics of Imperfect Competition, London: MacMillan.

Rognlie, M (2014), “A Note on Piketty and Diminishing Returns to Capital”, MIT Working Paper, Cambridge.

Wei, T (2014), Estimates of Substitution Elasticities and factor-Augmented Technical Changes, Center for International Climate and Environmental Research (CICERO), Oslo, Norway.

Young, A T (2010), US Elasticities of Substitution and Factor-Augmentation at the Industry Level, Working Paper, College of Business and Economics, West Virginia University.

1. In Canada, capital gains and dividends are the most lightly taxed forms of income, by a very wide degree. Nevertheless, the labour share of income has declined.

The author’s policy prescription–for lighter taxes on capital to augment labour share of income–is an automatic fail.

2. I can’t believe anybody would have the nerve, after all our recent experience, to suggest that “technical change that makes labour more productive” will increase labour share of income. That is not what is happening.

Quit prevaricating, and just tax the bloody capital already.

Not for nothing do you merit Senior Fellow, Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

I’m with Roland. The guy’s argument is based on a perceived and nebulous correlation. Enough of this High-Priest Sophistry. Start taxing all those off-shored Trillions!

It’s based on the demonstrably false notion that wages are set by “the market” and are not a function of the power of capital over labor (reserve army, you work or you starve, etc.) and the political arrangements of the State at any given juncture (do they support or suppress unions, what is the tax structure like, protectionist versus “free trade”, etc.).

that is the market

I would quibble with part of that, though. It’s not capital over labor. Capital is labor; that’s where it comes from. The notion that those are separate things is one of the core flawed premises of establishment economics.

The power interests in our system of political economy do not come from aristocratic titles and religious decrees and superhuman DNA and alien overlords and other types of non-financial inheritances. They come from financial compensation derived from labor. Incredibly obscene compensation.

Wage inequality, not capital formation, is the problem.

Changing what you pay in the form of consumption taxes DOESN’T change income disparity. By definition. It may change purchasing power differentials, but it does nothing to change income. The income is already made by the time you pay the tax on your Tesla. This man is either an idiot for not seeing something that obvious or he has a hidden agenda. And by taxing capital less, those who have great gobs of capital already get to keep more, thus making the wealth disparity (which is what really counts) worse.

If this guy is trying to say something about the vast income gap and that something should be done to reverse it, this is a monumental fail. If he is being a Trojan Horse, he’s going to have to be a little less obvious if he thinks anyone with brains will accept this nonsense.

I think Lambert is trolling us…

I wanted to see what people had to say. After all, the author worked for the Clintons once. And you never really stop working for the Clintons, not even in the Peterson Institute. Eh?

Adding, that’s what I meant by “squaring the circle.” Reducing taxes on capital to help workers… That’s something a DLC Democrat could sell!

It’s why I love this place. Every now and then you throw us a curve ball to see if we are paying attention. And this audience doesn’t let any thing get by,

It looks smells and tastes like bullshit. Its a very roundabout way of re-stating the idea that “a rising tide lifts all boats” (Limbaugh 1993)

I’m still waiting for my boat to go up. I’m pretty sure millions of others are too.

Take another look at the author’s cred’s: The Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics – that is a give away right there.

Also when I see anything that combines “government” & “Harvard”, I can’t help but think “Larry Summers”.

http://www.sourcewatch.org/index.php/Peter_Peterson

Anyone excepting a check from this group is not a friend of Labor.

You got that right!!

Yep. I think the hidden agenda is the more likely option here. This reminds me of all these recent proposals to subsidize the payment of slightly higher wages through cutting taxes on the “job creators.” In other words, have the not-quite-destitute (through their taxes) pay the already destitute a bit more, while the billionaires get to keep an even larger share of the pie!

Actually, he is improving on “trickle down”. He’s proposed trickle down plus a consumption tax!

‘Course none of these Big Guys seem to be aware of my 9.3% sales tax.

“The policy implications of this alternative explanation are profoundly different from those advocated by Piketty. Piketty advocates taxing capital. But if σ is < 1, increasing taxes on capital could lead to further reductions in labour’s share! Paradoxically, with σ < 1, policies that increase investment and the supply of capital could achieve more equal distributions of income. Accordingly lower taxes on capital and a progressive consumption tax could be the most effective approach to boosting investment and reducing US income inequality."

Does the author have evidence that lower taxes on capital will boost capital formation? Or are we just going to assume that magic happens when we lower taxes?

Also, conveniently not listed is the idea that maybe….just maybe the STATE could do a little more investing instead of tinkering with tax rates and hoping for the best!?!?!

Overall, I did enjoy the revelation that trickle-down theory is still getting taken seriously and published!

Lets start by looking at this statement:

“There are several plausible reasons for this development — globalisation, automation, weak bargaining power of labour, political capture, higher markups — but the natural starting point for explaining factor income shares is the theory of the functional distribution of income enumerated by John Hicks (1963) and Joan Robinson (1932) in the 1930s.”

Nope, the natural starting point isn’t that piece of work.

The natural starting point would be observing what is actually happening. The simple reason for this developement (capital obtains a larger share at the expense of labour) is simply due to change of bargaining strength. That reason can be broken down into smaller sub-reasons but in the end the share is determined by bargaining.

Collective bargaining is seen as something bad. Well, not if companies jointly do it, only if labour does it. No collective bargaining and the collective loses out but luckily we are only focusing on the individual winners not ever on the collective….

The collective would benefit by sharing the existing work – more vacation days would be one obvious way of sharing the existing work, another would be to enforce legislation regarding maximum hours worked. But that would ‘hurt’ the winners….

They’d be getting less of the surplus value generated so the ‘winners’, workaholics and capital owners, will claim that it is impossible.

Not only that it is impossible they’d also claim that since work is good for character then less work is bad for character… Optimisation of hours worked vs free time can only be done to fit the needs of the workaholics and capital owners, anything else would just be crazy or?

& a technical critique of the study: Those ratios aren’t following a smooth curve, they are comprised of discrete steps. But I suppose by averaging out everything in an economy then the theory will give the (preferred?) recommendation.

Well, exactly. One guy working on a computer is never going to be substitutable for 100 guys with shovels, period. Computer guy’s notional labour productivity is massively higher because of the computer. But if the 100 shovel guys acquired computer skills, all that would happen is that the wage share of computer guys would fall because “free markets.” That’s why the “skills-driven” approach of the DLC crowd is such bullshit. All it will do is lower the cost of highly-productive labour even further.

The only way to increase labour share of national income is to fight for it.

Reading stuff from the Harvard/Peterson Institute Underwear Gnomes is truly painful.

But after the huge jump over the gooblygook, we arrive at the final glorious step – PROFIT!

“Accordingly lower taxes on capital and a progressive consumption tax could be the most effective approach to boosting investment and reducing US income inequality.”

The one thing that kept going thru my head while reading this mindfck was Lambert’s favorite line – “where’s the agency in all this?”. The second is what’s all this concern about capital-labor substitution when we are up to our ears in news about labor-labor substitution?

BTW: I have worked in manufacturing jobs where we actually did capital investment. Economists would be well served if they tried it once and got a feel for what it is before making up all these theories. The next would be to review some old textbooks on the structure of production – like basic differences between a value added economy that does manufacturing vs a distribution/retail economy that flips products as quickly as possible.

Just more of the old Trickle Down econ theory.

See this Non Sequitur cartoon on trickle down:

http://www.gocomics.com/nonsequitur/2015/10/16

well, i guess the peanut gallery isn’t all that on board with this one. LOL

It’ hard to be an economist. let’s not forget that. That’s why Ed Bucks from MIT, the mathematical economist, ended up in a tree watching deer through binoculars. He flipped out when he realized nothing he thoought was truthful and rigorous actually made any sense at all. That’s a hard thing to confront but he did. The fact that he spends his days sitting up in a tree in the woods observing nature for insights about reality just show you what ontological shock can do to you. We’re working on getting him down before the winter sets in.

If he comes out of the woods with a fancy mathematical model (with lots of sigmas and taus n stuff) for explaining the seemingly stochastic appearance pattern for deer, do the man a favor and shoot him.

Re: “We’re working on getting him down before the winter sets in.”

Please be careful in the climb down from the blind. Extraction (and extrapolation) can both be difficult and fraught with potential for error. Keeping in mind the admonition of former Yankee catcher Yogi Berra that “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”, it seems to me that the empirical research of this particular economist offers a foundation that you could build on, at least in theory.

… “Some economists are fighting back by extending the borders of the discipline. One is MIT economist Ed Bucks, who is studying the grazing patterns of herds of deer for insights into how market actors make decisions under constraints of both scarcity and information. “Deer don’t know where the best grazing areas are in a forest,” said Professor Bucks to a reporter, “and when they find them they usually eat everything in sight. That’s a lot like people.”

(Reference readers’ comments section: http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/06/the-empirical-shift-in-economics.html)

maybe if we dress up in Bigfoot suits and throw rocks at him from a distance we can scare him down and send him running.

it would be tough love.

Reading this kind of economic gobbledygook is way out of my wheelhouse, but it sounds a little bit like an idea advanced by former Labor Secretary Robert Reich in rebuttal to the distortions caused by the Bush tax cuts in his book Supercapitalism. Abolish the corporate tax, but also abolish the ridiculously lower income tax rate on capital gains.

The idea is to encourage reinvestment, which requires the employment of more labor. Lower income tax rates on capital gains don’t encourage reinvestment, they are simply welfare for the rich. However, this author’s “consumption taxes” seem regressive as well, more “heads I win, tails you lose” for his Harvard benefactors, since much consumption by the looting class takes place offshore.

Abolishing corporate and business tax and paying for it by increasing sales tax is exactly what Kansas’s GOP Brownback admin has done at the state level. The results are lower growth, a terrible budget hole, reduced public services and a few much richer businessmen who make campaign contributions. Anyone considering this nonsense should take a close look at Kansas.

If you want to encourage business investment, then tie tax deductions directly to business profits being invested in capital investment and hiring in the US. And shutdown offshore tax dodges for US companies.

Something interesting is going to happen with all these theories and models to save capitalism from and for itself. Very soon capitalists will be called upon to invest in saving the planet. I can see it now. It will be big capital’s “can do” moment. And the wonderful irony is that there is no money in it at all. God only knows what they will substitute. Can’t wait to read the Peterson Institute’s blabber on that one.

I’m not buying this guy at all. Sounds like self-interest at work. Surprised that NC ran this piece. Do Lambert and Yves really fall for this tripe, or do you just post an article like this once in a while to see if your readers are paying attention?

I don’t see the mystery about declining labor share. Neoliberalism benefits the business class and hurts the working class. If it didn’t, the business class wouldn’t support Neoliberalism !!!

Btw, is the reduced share for labour (to the benefit of capital) a bug or a feature of the implemented policies?

Tweaks to the tax code, resulting in more money and power for the rich; the one-size-fits-all solution for every problem according to neoliberalism.

Well, Hillary said it herself, though it wasn’t her quote, Capitalism needs to be saved from itself…Meanwhile, the theories of “John Hicks (1963) and Joan Robinson (1932) in the 1930s” perpetrated the mentality via their pseudo science of economics master propaganda plan, that has allowed us to fall fatally and irrevocably into catastrophic extinction. Nope, I prefer the theories of more “up to date” thinkers. Give me Thomas Piketty any day!

“Capitalism needs to be saved from itself.”

Boilers always have regulators which controls the flow of steam and pressure. Without it, the machine runs rough or risks exploding from too much pressure. But we don’t say boilers need to be protected from itself.

Regulation is a necessity found throughout nature and technology. The insane part is that capitalism doesn’t need regulation.

As if government subsidized private credit creation were honest!

Here’s an honest example:

A has a factory. B are her workers. A wants to buy new machinery to improve production. She borrows from her workers at an honest rate (or sells new shares to them) and both A AND B profit from the new investment.

But with government subsidized private creation A can bypass her workers’ savings and borrow at suppressed interest rates from the government subsidized banks. Now only she and the banks profit.

There’s nothing honest about government subsidized private credit creation. To attempt to regulate it is to attempt to regulate theft. That makes one an accomplice to theft, no?

Okay, what the F— does he mean by “substitution?”

It’s when you do capital investment and that may have some impact[up or down] on labor [hours? he’s not particularly good with consistent units – or geography – or groaf] – the new way – call up Goldman and give them the name of a S&P 500 company you want to take over.

Good question. The author doesn’t appear to have any clear definitions of any key terms, from substitution to capital itself.

Within establishment economics of factors of production, he’s describing the concept of hiring laborers to make and service machines and other equipment that then do the work instead of hiring laborers to do the work directly. In a micro sense, this has some value for looking at the operations of individual firms. It’s helpful to know things like the cost of wages and the cost of raw materials and the cost of supplies and the cost of rent and so forth. It might very well be that five office workers with computers and an IT support staffer is a more efficient use of resources than ten office workers with typewriters – even if a computer is a lot more expensive than a typewriter – and so in micro view, this net switch from ten employees and ten outdated machines to six employees and six new machines is called substitution.

But in a macro sense, in the big picture, it doesn’t mean anything. The same amount of wealth is being produced. There is no actual distinction among land, labor, capital, knowledge, etc. The economic value of each derives from human labor. That we reward some forms of labor more highly than others is a choice of political economy.

Substitution means choosing a different point (combination of K and L) .. presumably from among the choices available with given resources; the usual assumption is that the tradeoff in substitution is reflactedd in the relative prices of the inputs. If r is twice w, then the tradeoff is two units of L for one of K. Needless to say a lot of hand-waving when it comes to comparing the model with the real world.

I am having trouble understanding this part of the argument.

It would seem if substitution is easy, and the cost of capital falls, then people would quickly replace labor with capital. Likewise is substitution was hard, then things would seem intuitively to be more stable.

So I am not saying what the author is saying is wrong, I am just not following this argument. For example, if a robot costs $90,000 and last for 5 years I wouldn’t be replacing my fully loaded employees at $20,000 per year, if the interest rates were 6%. But if I could borrow at 0%, adios my compadres. So I would shift from labor to capital very quickly.

Yes, it is confusing. But I will try to help you understand the model. First, quit thinking about the the real world! The real world is not part of the model!

OK Now, There is no borrowing in this economic model. In fact there is no money. There are two inputs that produce an output: labor (L) and capital (K). . All factors of production (ie., L and K as there is no land or natural resources) are fully employed at all times. r then is the cost of using capital and w is the cost of using labor. So, saying that the cost of capital is high means that r is high. High is a relative concept. Relative to say a previous value. Economists who use these models are using comparative statics. What if the ratio of r to w was higher or lower then what would happen …

Obviously, there is much silliness. Most obviously full employment, and no politics (including no monoplies, no rents, no rent seeking, etc.). The model and its paraeters determine r and w. The only policy variable is taxation of the inputs or the output!!!

Labour and capital are not the only factors of production.

High school political economy course will tell you that there are three – land labour and capital.

This disappearance of the landlords is a hint enough of what is wrong and who is skimming all the production.

Confusion between capital and “land” is not an innocent oversight.

My earlier remark was intemperate, so I re-read and re-considered the article. I still find the author’s piece poorly written and poorly argued.

The author’s entire argument depends upon a speculation over whether sigma is less than one, or greater than one.

The author does not bother to give a good explanation of why he thinks sigma is less than one. He merely cites a few studies, without bothering to summarize the findings or methodology of those studies. That made me grumpy, because like many people at NC, I am not fond of “homework assignments.”

Moreover the author does not address the possibility of a falling w as a cause of declining labour share of income.

Finally, the theory might be flawed in the first place. A falling w, for instance, might not necessarily lead to increased use of L. Is the author blind to the decline of labour force participation among working-age cohorts in the USA and some other developed countries, even though real individual employment wages have fallen?

And to add some speculation of my own, what if wages fall to a sub-Ricardian level (i.e. to a level too low for the workers to be able to raise a replacement generation of workers to perform the same work). This idea might sound far-fetched, but consider the decades-long reality of the sub-replacement demographics of the so-called “middle class” in most developed countries. Mounting education and housing costs have made the replacement of the working generation too expensive. As a result, you see a situation in which falling w can actually lead to falling L.

Brings me back to graduate school where political economics was marginalized in favor of these kinds of economic models. Full employment, no money, prices totally determined by marginal productivity of the only two inputs, K and L, and the marginal productivity determined by the models parameters. I have to say while I do not keep up with mainstream economics, even Stiglitz has abandoned a lot of this stuff. At least he knows there is money, unemployment and politics in the real world and that labor and labor power are different (even if he doesn’t use those terms).