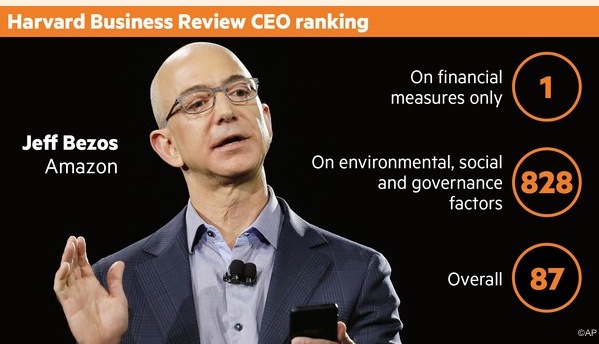

Harvard Business Review just published its annual ranking of “Best Performing CEOs in the World“. The noteworthy part, picked up by the Financial Times, is that last year’s numero uno, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, fell from his perch to number 87 based on Amazon’s poor social responsibility marks. The new “best CEO” is Lars Rebien Sorensen of Novo Nordisk, a biotech player best known for a diabetes drug.

The Harvard Business Review deserves credit for this small but important symbolic step to redefine corporate success away from purely financial considerations and to include broader societal impact. As the story stated:

How did this mild-mannered, bespectacled executive land in the #1 spot on our list? It’s partly due to his company’s (darkly) fortuitous decision years ago to focus almost exclusively on diabetes treatment. The runaway global growth of the disease has driven up the company’s sales and stock price.

But his standing also reflects Novo Nordisk’s deep engagement with social and environmental issues, which now factor in to our calculations. “Corporate social responsibility is nothing but maximizing the value of your company over a long period,” says Sørensen, who has been with the company for 33 years. “In the long term, social and environmental issues become financial issues.”

Having said that, the Harvard Business Review is only taking small steps in pressing for broader notions of performance and accountability. The financial metrics count for 80% of the total score, and the “social responsibility” measures, a mere 20%. But this is still a long-overdue move in a better direction.

Perhaps as important, the Harvard Business Review methodology unwittingly allows the public to see which CEO is the most predatory, by looking at the divergence between its financial standing versus its score on “environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance.” Now admittedly this is not identical to a measurement of impact on the community, broadly defined. For instance, governance issues tend to be of more concern to shareholders than other stakeholders, but it is true that the companies with the most insulated, imperial CEOs have a tendency to play fast and loose as far as the law and regulations are concerned (one example is Jamie Dimon, who is still both chairman, CEO, and president of JP Morgan, and managed to get away with appallingly lax internal controls and misrepresentations to shareholders and regulators, and has also been widely reported to bully central bankers like Mark Carney and Ben Bernanke).

This image from the Financial Times article nicely sums up the case for Bezos as top predator:

And mind you, this is even worse than it looks. Amazon is not 828 out of a presumed 1000 companies. It’s 828 our of 907. And it’s pretty hard for a service business to do the environmental damage of, say, an oil company (BP’s Deepwater Horizon) or a chemical producer (Dow’s Bhopal disaster, or the more recent horrific explosions in Taijin). So it’s not an exaggeration to see Amazon as being as bad as it can be in terms of broader community impact for a company of its type.

And it’s confirmed if you look at the spreadsheet that the Harvard Business Review courteously made available so outsiders can see how they came up with their ratings.

Sadly, but not surprisingly, there are companies with large gaps between their financial performance scores and their ESG ratings. After all, this is feature, not a bug, of modern capitalism.

Salesforce Tencednt of Hong Kong,, which is second only to Amazon in financial marks, is 630 in the ESG tally. Whole Foods is number three in the financial ranking versus 600 for ESG. The top-scoring financial firm, Blackock, is 5th on the return metric and an only somewhat terrible 483 on ESG. Two foreign companies show similar wide disparities: number 8 in money terms Japan’s Fast Retailing, comes in at 499 on ESG; Taiwan’s Hon Hai Precision Industry, is 9 in the financial ranking and 509 on ESG. And a company that is widely hated, Monsanto, scores 14th in financial results and 693 on ESG, putting it well ahead of Amazon.

Readers may also understandably wonder about how to devise an annual “environmental, social, and governance performance” rating when serious damage takes decades to inflict, while financial performance is an annual affair. The ESG rating is also black box. From the HBR article:

To measure CEOs’ performance on nonfinancial issues, HBR consulted with Sustainalytics, a leading provider of environmental, social, and governance research and analytics. Sustainalytics, which works primarily with financial institutions and asset managers, rates firms’ ESG performance on a scale from 0 to 100. Using the Sustainalytics data, we ordered the 907 CEOs from best to worst ESG scores to arrive at their ESG ranking.

For instance. that Whole FoodsESG rating of 600, no doubt due to its persistent cheating of customers, its anti-union efforts, and (mayhap) for being an upscale social responsibility poseur that pays workers less than a living wage. Amazon’s rating of 892 is closer to the bottom of the barrel. But how do you score the damage done by, say, a Monsanto, or by the well-funded and effective climate denialism of an Exxon? I spent some time thinking about how to come up with an annual “Most Evil Company” rating, and realized it would be too hard to pick apart long-term versus shorter-term actions.

Nevertheless, we’ve called on readers to boycott and/or limit their use of Amazon. It’s only when Amazon starts to pay a real price for its practices that it will be forced to make changes.

According to the Excel spreadsheet data, Salesforce is 13 in financial and 593 in ESG, while Whole Foods is 44 in financial and 447 in ESG.

Aiee, I tried very hard to read across those rows carefully, and more than once too! But this seems again to fall in the category of my terrible eye for typos. Thanks for the catch.

That spreadsheet only has details for the top 100 companies. I was curious who was at the top of the ESG table, but the best ESG rating in the top 100 is Novo Nordisk at 15. I sorted on the ESG column and noticed that a US company doesn’t show up until line 15, Cisco. In the top half of the table there are only 12 US based high ESG companies, with US companies dominating the bottom of the list. It is also interesting that companies that actually make things (industrial, auto) dominate over the services (health care, retail).

The day Jeff Besozabub gets his comeuppance will be a good day for humanity. One can hope……

If the stories on ambulances being on call at shipping facilities in Pennsylvania couldn’t ding the reputation of Amazon and Bezos very much, I seriously doubt this HBR story will have much of an impact. I suppose it’s nice to see the captured interests of a mainstream publication thinking a little differently though.

This image from the Financial Times article nicely sums up the case for Bezos as top predator:

Jeff wants to be number one at everything. That is exactly the type of recognition he desires.

Sounds like a good summer internship study / program. There are evil companies in elder care too, and that one would be a difficult metric to generate.

“Amazon’s rating of 892 is closer to the bottom of the barrel. But how do you score the damage done by, say, a Monsanto, or by the well-funded and effective climate denialism of an Exxon? I spent some time thinking about how to come up with an annual “Most Evil Company” rating, and realized it would be too hard to pick apart long-term versus shorter-term actions.”

Did you check out the gender column?

Wow – only two women.

Bezos is worse than Jamie Dimon, Monsanto, the oil companies, the defense industry? Really? This seems purely arbitrary unless they are willing to get more specific about their ESG. If they were merely calling him America’s worst boss they might have a point.

Of course Amazon is disrupting retail in a way that may have significant impact on the economies of towns, large and small, across America. Or it may turn out to be a flash in the pan which is why Amazon seems eager to diversify into content. I’m just not sure how useful this sort of value judgment is. Some of us feel that Harvard might want to give itself a “social responsibility” rating.

Upon reading that ‘Sustainalytics’ works directly for the companies that it’s supposed to be analyzing (” Sustainalytics, which works primarily with financial institutions and asset managers…”), my first thought was of Matt Taibbi’s awesome work describing how asset ratings agencies like S&P and Fitch were heavily corrupted both before and after the 2008 crash because they received their money from the companies whose financial products they rated rather than the companies and people who relied on those ratings being accurate. Seems like a very similar market dynamic with Sustainalytic.

“small but important symbolic step to redefine corporate success away from purely financial considerations and to include broader societal impact….”

A tiny crack in the Chicago School/neoliberal dominance? good.

I’m intrigued by the challenge of a damage construct and metric.

One way is like the space time metric of physics, aka 4th dimension that allows us our mobile phones etc. I.e. one factor would be scale of life damaged, from humans to liveable environment. Integrating that damage over time would give a time measure of impact, I.e. on future generations.

For example, 250,000 estimated farmer suicides in India from sterile monsanto seeds is many orders of magnitude of persons plus environment x at least 1 generation. So, to make a prospective construct, some max, min limits would be provisionally established.

All well and good, if writing a chapter of Dante’s Inferno….damage is too non linear to compare easily, I.e. considering damage of JD & JP Morgan: the illegal foreclosures, millions out of homes and jobs, crony corruption of AG office, White House, Congress.

So it would seem there needs to be a 3rd factor, of impact on power structures. Bezos with his Wapo and DoD incursions may only be a small player on the JP Morgan roulette of death culture, but clearly there.

But I feel it’s important too remember the codependent, enabling consumers. No significant numbers close their Chase or Amazon accounts. They are also to blame along with the CEOs and shareholders!

The Freedom Caucus questionnaire / demand list is quite the read. For those who are on any form of “government aid”- including Medicare or Social Security…you are screwed. http://www.politico.com/f/?id=00000150-49be-d501-ab5d-6dbf7cd70000

Another observation: the list will continue to evolve each time they perceive a “wrong”. The complaint about EX-IM bank had to have been added, because the action was only from last week.

Does that mean that they would really support any non-Freedom caucus individual?

I am a schmuck. Only recently have I decided to eliminate Amazon from my life, and this three years after they were excoriated by a Parliamentary Inquiry in the UK as to their tax responsibilities and financial practices.

My apologies.

Bezos has purchased the Washington Post.

Hence his status as #1 has been restored.