Lambert here: The focus is on European parliamentary systems. Is America different? Exceptional?

By Manuel Funke, Doctoral Candidate in Economics and Social Science at the Graduate School of North American Studies, John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Free University Berlin, Moritz Schularick, Professor of Economics, University of Bonn and CEPR Research Fellow, and Christoph Trebesch, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Munich; Research Affiliate, CESifo and Kiel Institute for the World Economy; and CEPR Research Affiliate. Originally published at VoxEU.

Recent events in Europe provide ample evidence that the political aftershocks of financial crises can be severe. This column uses a new dataset that covers elections and crises in 20 advanced economies going back to 1870 to systematically study the political aftermath of financial crises. Far-right parties are the biggest beneficiaries of financial crises, while the fractionalisation of parliaments complicates post-crisis governance. These effects are not observed following normal recessions or severe non-financial macroeconomic shocks.

With the catastrophe of the 1930s in mind, the fear of ongoing political radicalisation in the wake of economic and financial disasters looms large in the public discourse. What does history have to say about the political after-effects of financial crises in modern democracies? Can we, over the long run of modern history, identify systematic shifts in the political landscape after financial crises?

We are not the first to ask such questions. De Bromhead et al (2012) show how the Great Depression in the 1930s triggered political extremism. Using more recent data, Grüner and Brückner (2010) find that low growth is associated with more extremist voting, while Mian et al (2012) find that financial crises are followed by fractionalisation and polarisation of parliaments. Related, Bloom et al (2011) demonstrate that policy uncertainty is particularly high after financial crises.

In a new paper (Funke et al 2015), we conduct the most comprehensive historical analysis on the political fall-out of financial crises to date. We trace the political history of 20 advanced democracies back to the 1870s and construct a dataset of more than 800 elections from 1870 to 2014. We then complement this dataset with existing data on more than 100 financial crises and with historical data on street protests (demonstrations, riots, and strikes).

Increasing Polarisation: Hard Right Turns

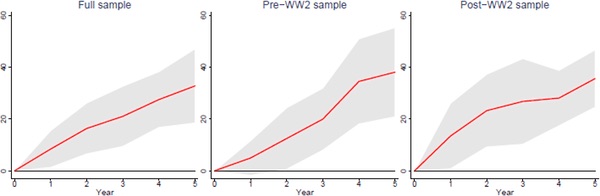

Our first main finding is that politics takes a hard right turn following financial crises. On average, far-right votes increase by about a third in the five years following systemic banking distress, as shown in Figure 1. This pattern is visible in the data both before and after WWII and is robust when controlling for economic conditions and different voting systems. The gains of extreme right-wing parties were particularly pronounced after the global crises of the 1920s/1930s and after 2008. However, we also find similar patterns after regional financial crises, such as the Scandinavian banking crises of the early 1990s. Moreover, we identify an important asymmetry in the political response to crises – on average, the far left did not profit equally from episodes of financial instability.

Figure 1. Far-right vote shares after financial crises (local projections)

Notes: Each path shows local projections (see Jordà 2005) of the cumulative change relative to peak for years 1–5 of the Recession and recovery period. The red line refers to the average path in financial crisis recessions and the shaded region is a 90% confidence interval. The left panel covers the years 1919-2014, excluding World War II, the middle panel 1919-1938, and the right panel 1950-2014. The dependent variable is the combined vote share of all electorally successful (vote share > 0.1%) far-right political parties in the most recent general election.

Increasing Fragmentation: Governing Becomes More Difficult

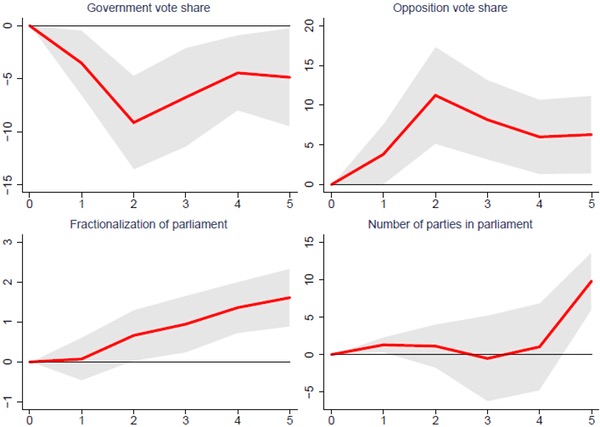

The second key finding is that governing becomes more difficult after financial crises. Government majorities shrink and parliaments tend to fragment, confirming the findings of Mian et al (2012). Using the depth of our historical dataset we can show that these effects have become stronger over time. The local projections that use post-WWII data are presented in Figure 2. The figure shows that following the post-1950 financial crises, government vote shares drop, while the opposition vote share increases (upper panel). Parliaments become more fractionalised and the number of parties rises (lower panel). All this is bad news for effective governance in the post-crisis period – at a time when decisive political action may be most needed.

Figure 2. Voting outcomes (post-WWII crises)

Notes: Each path shows local projections of the cumulative change in 100 times the logged variable relative to peak for years 1-5 of the recession and recovery period. The red line refers to the average path in financial crisis recessions and the shaded region is a 90% confidence interval. Post-WWII sample: 1950-2014.

People Take to the Streets

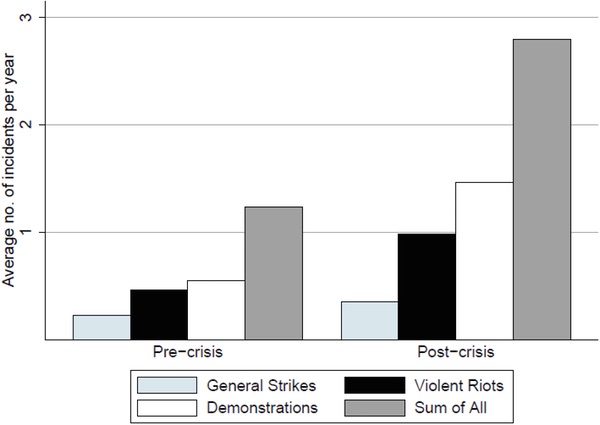

Financial crises do not only trigger political protest at the polls, but also in the streets. Figure 3 shows the average yearly number of general strikes (light blue columns), violent riots (white columns) and anti-government demonstrations (black columns) in the five pre-crisis years (left panel) compared to the five years post-crisis (right panel). We use the entire sample for which these data are available (1919-2013). The figure indicates a strong increase in street protests in the crisis aftermath (the grey bars show the sum of all three protest types); the average number of incidents more than doubles following financial crises. This difference is statistically significant at the 5% level. More specifically, the average number of anti-government demonstrations almost triples, violent riots double and general strikes increase by at least one third.

Figure 3. Street protests

Notes: The figure shows the average number of street protest incidents per year, including the number of general strikes (light blue columns), violent riots (black columns), anti-government demonstrations (white columns) and the sum of the three (grey columns). The left panel refers to pre-crisis averages (five years) and the right-hand side bars to post-crisis averages (five years).

Persistence: The First Five Years are Critical

How persistent are these effects? We find that the first five years are critical and most effects slowly taper out afterwards. A decade after the crisis hits, most political outcome variables are no longer significantly different from the historical mean. This is true for far-right voting and also for government vote shares and the parliamentary fractionalisation measure. Only the increase in the number of parties in parliament appears to be persistent. The comforting news from our study is that the political upheaval in the wake of financial crises is mostly temporary.

Financial Crises are Different

How do the political effects of financial crises compare to the aftermath of other economic downturns (i.e. those not involving a financial crash)? To shed light on this question, we compare our main results to two alternative ‘treatments’. Specifically, we compare the aftermath of ‘financial crisis recessions’ (associated with a financial crisis), to that of ‘normal recessions’ (not associated with a financial crisis), and episodes with particularly severe GDP declines but no financial crisis (which we term ‘non-financial macro disasters’). The bottom line is that financial crises stand out. They are followed by significantly more political instability than other types of economic crises.

This raises the question – why are financial crises different? One explanation is that financial crises may be perceived as endogenous, ‘inexcusable’ problems resulting from policy failures, moral hazard and favouritism. In contrast, non-financial crises could be seen as ‘excusable’ events, triggered by exogenous shocks (e.g. oil prices, wars). A second potential explanation is that financial crises may have social repercussions that are not observable after non-financial recessions. For example, it is possible that the disputes between creditors and debtors are uglier or that inequality rises more strongly. Lastly, financial crises typically involve bailouts for the financial sector and these are highly unpopular, which may result in greater political dissatisfaction.

Implications

The typical political reaction to financial crises is as follows: votes for far-right parties increase strongly, government majorities shrink, the fractionalisation of parliaments rises and the overall number of parties represented in parliament jumps. These developments likely hinder crisis resolution and contribute to political gridlock. The resulting policy uncertainty may contribute to the much-debated slow economic recoveries from financial crises.

In the light of modern history, political radicalisation, declining government majorities and increasing street protests appear to be the hallmark of financial crises. As a consequence, regulators and central bankers carry a big responsibility for political stability when overseeing financial markets. Preventing financial crises also means reducing the probability of a political disaster.

References

Bloom, N, S R Baker and S J Davis (2011) “Policy uncertainty and the stalled recovery”, VoxEU.org, 22 October.

de Bromhead, A, B Eichengreen and K H O’Rourke (2012) “Right wing political extremism in the Great Depression”, VoxEU.org, 27 February.

Funke, M, M Schularick and C Trebesch (2015) “Going to extremes: Politics after financial crises, 1870-2014”, CEPR, Discussion Paper No. 10884.

Grüner, H P and M Brückner (2010) “The OECD’s growth prospects and political extremism”, VoxEU.org, 16 May.

Jordà, Ò (2005) “Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections”, American Economic Review, 95(1): 161-182.

Mian, A, A Sufi, and F Trebbi (2012) “Political constraints in the aftermath of financial crises”, VoxEU.org, 21 February.

Think this is a good point, and would like to add to your line of reasoning that the funding of ISIS and so called “moderate rebels” in Syria because regime change by US & it’s allies, is producing swift blowback along the lines you talk about from the financial crisis. The Paris attacks – supposedly by ISIS & Co (the same “moderate rebels” Obama is funding regardless of what we or they call themselves) – is energizing right wingism on a lot of fronts in Europe & the US. Even to the badly misinformed US public Obama looks to have egg on his face because of the Paris attacks, and he is now having to spend energy fighting political blow back from the Paris attacks – like Congressional moves to target Muslims and refuges. While I’m not certain Obama actually gives a rats arse about the refuge crisis he’s caused, he’s on record at least “in words” if not deeds to be against the the sort of racists backlash that his own policies have helped to create.

As global creditors come for their money and impose austerity, the nation turns inwards and becomes nationalistic.

The outside world is now the enemy.

Same old, same old ……

1920s/2000s – high inequality, high banker pay, low regulation, low taxes for the wealthy, robber barons (CEOs), reckless bankers, globalisation phase

1929/2008 – Wall Street crash

1930s/2010s – Global recession, currency wars, rising nationalism and extremism

1940s/? – Global war

We are nearly there with the Middle East on fire and the two nuclear super-powers at each other’s throats.

Nuclear weapons kept the Cold War “cold” for decades and so we may be able to miss out on the global war phase as the nuclear super powers guarantee only MAD (mutually assured destruction).

Central Banks have certainly done their part (in the short term) to preserve the political system and ‘financial stability’ (read: rising equity markets). I will give them that. It remains to be seen if legislators will finally act to do their part, which must include redisitribution of wealth downward. The CBs have only accomplished redistribution upward, which is counter-productive to social stability. I believe we will need to see more social unrest to move the oligarchs and their legislative employees out of complacency and into action. I believe they will need to feel some fear.

I hope I’m wrong.

That’s more or less my belief too Mike.

There is a projection that increased automation of production will more or less remove workers from factories. There is no corresponding political effort to redeploy them, indeed the costs of education are in orbit.

It would be reassuring to see a great investment in distance learning with more bandwidth provided to broadcasters of academic programs so a slight avenue for escape is opened to the great mass of the population. I don’t see that happening and instead we see an external proletariat being forced to care for itself – the ungoverned. Mad Max.

I have no expectations of the Legislature of any western country acting in the interests of its constituents until, as you hint, a guillotine is erected at the casino doorway.

Harder to compare European parliamentary systems with the less democratic two-party US system (which seems to have become even more skewed towards two main parties, i.e., even harder for new parties to form or be effective).

Also, more challenging to compare perceived political effectiveness. I’m not aware of the kind of pork-barrell omnibus legislation occurring in parliamentary style systems, of the kind produced by the US systems with its committee stages that end up producing a different bill than its title, and loaded with local/regional pork. This could have an impact on the extent to which politicians can or cannot “spin” legislative or executive actions, which can in turn affect public perceptions (which would in turn impact the extent of popular sheep-like docility vs demonstrations and strikes).

Speaking of media, wouldn’t the tighter and tighter consolidation of media (globally!) and the degree of interpenetration of governments with media empires also play a major role in public perceptions (including of public empowerment or otherwise) and hence impacting the extent of social obstreperousness?

If I may interject my own crackpot opinion, the Tea Party is in fact a new party.

IMO, it WAS a new party, but then it was coopted into the Republican party. Just like the Populist party in the late 19th century was absorbed into the Democratic party.

By Manuel Funke, Doctoral Candidate in Economics and Social Science at the Graduate School of North American Studies, John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies, Free University Berlin; Moritz Schularick, Professor of Economics, University of Bonn and CEPR Research Fellow; and Christoph Trebesch, Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Munich, Research Affiliate, CESifo and Kiel Institute for the World Economy, and CEPR Research Affiliate. Originally published at VoxEU.

Semi-colons can be used in a series in order to separate items that contain commas. Rarely are semi-colons used in an ordinary list. Here the semi-colon makes clear the names of the three authors.

In the listing of causes for financial crises, the authors fail to name fraud and corruption which were both present for the 1939 Depression and the 2008 Great Recession. I wonder why?

I know. The authors also beg the obvious question: So if finance is so important to stability why don’t societies reconfigure finance to create durable governance and stability? Instead, by ignoring the real question, they twist it a half-turn and try to fudge the point by implying that stability must be configured to create durable finance… And we all wonder why it is we seem to be living in a half-way house.

> The comforting news from our study is that the political upheaval in the wake of financial crises is mostly temporary.

This is not particularly comforting to me, since it seems to cease without fixing any of the underlying problems in general.

“Apres moi le deluge” – King Obama

Or, in the vernacular, “I’ll be gone; you’ll be gone.”

the first paragraph says it all; does anyone know anybody associated with the so called institutions that were probably created 20 minutes ago and will be all forgotten by Easter? I recognize nobody there. Do You?

Free University Berlin was created 20 minutes ago? :)

That political fragmentation (finding #2) follows right wing popularity surges (finding #1) suggests the latter may be temporary reactionary responses (knee-jerk) than homeostatic equilibrium-stabilization.

However, if each crisis pushes toward more deregulation and less control, then each crisis creates the self-fulfilling prophecy, or enabling condition, for the next, would it not?

Other factors missing from the model include the mostly-US-initiated military coups of democratically-elected socialist governments that attempt (successfully or otherwise) to respond to or avert crises.