By C.P. Chandrasekhar, Professor of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Jayati Ghosh, Professor of Economics and Chairperson at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Cross posted from Business Line

Everyone knows that 2015 was a terrible year for emerging markets – but exactly how bad it was has become clear only recently. Not only was it an annus horribilis in terms of net exports of goods and services, which declined sharply and even turned negative for some previously buoyant exporters, but it was also a time when capital flows reversed course. The downturns in both indicators have been much more widespread and substantial than they were initially expected to be, and even greater than mid-year assessments suggested.

In a previous edition of MacroScan, we used IMF data to show how net capital flows into developing Asia had declined significantly in 2014. This marked a break from the previous boom period when emerging markets – and especially those in developing Asia – could do no wrong in the eyes of global investors. But 2015 turns out to have been much more devastating for emerging markets across the world, including those in Asia. A new report from the Institute of International Finance (“Capital Flows to Emerging Markets”, IIF Washington D.C., 19 January 2016) indicates just how serious the swings in capital flows have been.

A significant feature of the IIF estimates is that they capture unrecorded capital flight that is typically expressed in the form of “Errors and Omissions” in the balance of payments data. Using the total of net inflows from non-residents into emerging markets across all regions minus the total of net capital outflows made by residents, and adding the effect of errors and omissions, the reports comes up with the surprisingly large figure of $735 billion net capital outflow in 2015, compared to a net outflow of $111 billion in 2014.

Much of this was driven by China: the IIF estimates that net capital outflow from China in 2015 amounted to $676 billion, including $216 billion in unrecorded net outflows. However, even excluding China, emerging markets as a group experienced negative capital flows in both 2014 and 2015, with the amounts significantly larger in 2015 especially once unrecorded flows are taken into account.

It is noteworthy that this was only partially because of foreign residents pulling their capital out of these countries. This certainly happened to some extent, but net capital inflows from non-residents to all emerging markets remained positive in 2015 at an estimated $293 billion. Rather, the more significant factor was that residents of emerging markets took their money elsewhere: net private capital outflows by residents amounted to as much as $824 billion, and the trend was evident in terms of both foreign equity investment and lending patterns. Unrecorded flows in the form of errors and omissions contributed to the bleeding, amounting to as much as $206 billion.

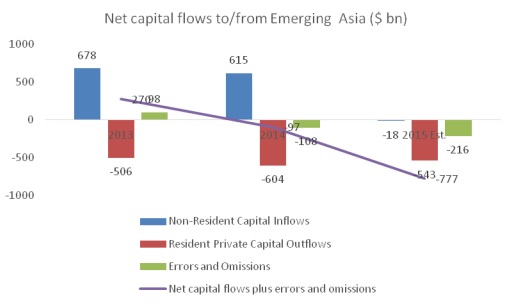

This pattern is particularly evident for developing Asia. The IIF study is based on data from seven countries (China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, South Korea and Thailand) that account for the vast bulk of cross-border capital flows in the region. Charts 1 and 2 show some important information that emerges from these data.

In Chart 1, the data on non-resident inflows includes both private and official flows (such as flows from official bilateral and multilateral sources, which are however very small). The resident outflows refer only to private flows, since the official outflows occur in the form of change in foreign exchange reserves. Chart 1 indicates the dramatic swings in the direction of net capital flows that have occurred in just three years. Net non-resident capital inflows into these seven Asian countries declined from nearly $700 billion in 2013 to an estimated negative figure of around $18 billion in 2015. The IIF in fact projects further decline in 2016. Since private net capital flows remained large over all three years, and so the declining net inflows meant overall declining capital account balances.

But the more significant swing has been in terms of unrecorded capital flows as suggested by the “Errors and Omissions” category: from a net inflow of $98 billion in 2013 to a net outflow of as much as $216 billion estimated for 2015. Once again this is hugely driven by what is happening in China in terms of unrecorded capital flight – the IIF estimates Errors and Omissions in the Chinese balance of payments to be greater than $200 billion in 2015. 3 But there is evidence of negative trends in other Asian countries as well, albeit to a lesser extent in terms of sheer volume.

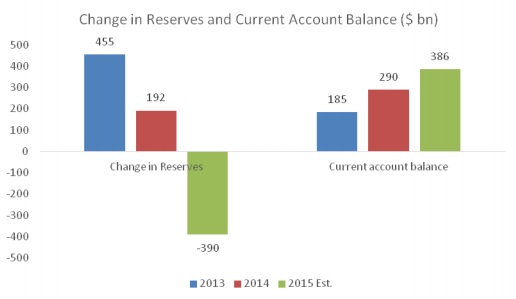

What is surprising is how this cannot be explained in terms of current account balances at all. In fact, current account balances for these seven countries taken together have been increasing all through and also increased in 2015, as Chart 2 shows. The estimated current account surplus in China for 2015 is $270 billion, but in fact of these Asian countries, only India and Indonesia showed deterioration of their current account balances (which were already in deficit) between 2014 and 2015. The other countries experienced slight improvements in current account balances – but this did not prevent the substantial capital outflow.

Such substantial swings in capital movements would have had even larger effects on exchange rates were it not for the use of foreign exchange reserves by central banks of some of these countries to intervene in currency markets. For these countries as a group, foreign exchange reserves declined by nearly $400 billion, but not all countries showed the same tendency for declining reserves. In China alone the foreign exchange reserves are estimated to have declined by $405 billion over the period, which is still not such a large drop considering that at the start of the year the country held more than $4 trillion of such reserves.

In other Asian countries, however, governments have chosen to allow their currencies to depreciate rather than use up reserves to prop up their exchange rates. This may reflect the urge to remain competitive in exporting in an increasingly difficult global environment. It could also result from the perception that even small declines in reserves in some countries can have disproportionate impact on investor expectations given the brittle and volatile behaviour of financial markets in the recent past.

All this bodes ill for the coming year. The IIF projections are similar to other gloomy prognostications about the global economy in 2016. But its assessment of the likely worsening of trends in capital flows may even be more worrying because it suggests that the behaviour of global capital markets will reinforce the downward pressures emanating from the slowdown in world trade, and may lead to further destabilisation of some important developing countries.

‘In other Asian countries, however, governments have chosen to allow their currencies to depreciate rather than use up reserves to prop up their exchange rates.’

One could amend ‘Asian’ to ‘developing’ and this statement would still be correct, ex China and Venezuela. Through its currency peg, China is lashed to the mast of tightening U.S. monetary policy, which is wholly unsuited for China.

According to Kyle Bass, “The IMF says [China] needs $2.7 trillion in FX reserves to operate the economy. They’ll hit that number in the next five months. Those who think they can burn it to zero and they have a few years ahead of them, they really only have a few months ahead of them.”

“When they lose money in their banks they’re going to have to recap their banks. They’ll have to expand the PBoC balance sheet by trillions and trillions of dollars. A Chinese devaluation of 10% is a pipe dream. It will be 30-40% by the end.”

Young Kyle is talking his book, of course. But with central banksters playing wildly discordant tunes, and China stuck with a currency peg that no longer suits its needs, something is going to break.

A previous Asian crisis in 1997 was the prequel. This is Act II — the heart of the drama.

Yah, the buccaneers and looters and corruptniks must be free to fly off their takings, leaving the dismembered bleeding mopes to finish the orpses off…

“Capital” Must Be Free!!!

A significant feature of the IIF estimates is that they capture unrecorded capital flight that is typically expressed in the form of “Errors and Omissions” in the balance of payments data.

. . . the IIF estimates that net capital outflow from China in 2015 amounted to $676 billion, including $216 billion in unrecorded net outflows.

This is the money showing up in Vancouver’s housing market and elsewhere. No price is too high when paying with loot.

Where did it go? Do we have numbers? What real estate markets?

What happens to those markets when the capital flight stops?

Is it just me or did I not get the memo….. I thought the term d’art was – Return of Capital – e.g. taking ones marbles and going home…

Capital outflow could be the proceeds of corruption going to perceived safe havens. The Chinese government being under pressure to deal with corruption could be part of the picture.

The government clean-up in China is becoming effective. Those officials who have been taxing citizens unauthorisedly have to get their savings out of the country.

One popular route has been million dollar single premium policies available in HK and payable in due course in Europe. Beijing has just enacted a limit on them of $5,000 which means instead of one policy you now have to buy 200. Its an inconvenience.

I shall return.

McArthur was very concise and Capitalism is nothing if not hypocritical. We push the free flow of capital without regulation, whether we go to war to do it or just use the drip method. Because freedom and democracy (too many layers of hypocrisy to sort thru here); then when everything ponzis out of control we say naughty naughty, your currency is way overvalued and we are going to short your currency, aka your capital. And then its a standoff on some principle that eludes morality until the country, China, burns thru its “reserves” which is money it hoarded by pure mercantile practices prompted by the mercantilists of the developed world and then the short sellers form a pact and think they can prevail but China thinks maybe not… and all this is done in the spirit of capitalism because as we all know only capital has any value… we just can’t define it.

China is now the workshop of the world.

China’s problems clearly illustrate the lack of global demand.

China manufactures its products from imported raw materials from other emerging economies, so these in turn suffer from the lack of global demand for China’s finished goods.

Global commodity prices and the Baltic Dry Index are at record lows illustrating this collapse in demand.

Demand from the Western consumer collapsed in 2008 and its Keynesian debt fuelled infrastructure spending has reached max. debt before the Western consumer has recovered.

Today’s supply side, trickledown economics is revealing itself for the disaster that it really is.

Ever heard of Einstein’s definition of madness “Doing the same thing again and again and expecting to get a different result”?

Today’s ideal is unregulated, trickledown Capitalism.

We had un-regulated, trickledown Capitalism in the UK in the 19th Century.

We know what it looks like.

1) Those at the top were very wealthy

2) Those lower down lived in grinding poverty, paid just enough to keep them alive to work with as little time off as possible.

3) Slavery

4) Child Labour

Immense wealth at the top with nothing trickling down, just like today.

This is what Capitalism maximized for profit looks like.

Labour costs are reduced to the absolute minimum to maximise profit.

(The majority got a larger slice of the pie through organised Labour movements.)

The beginnings of regulation to deal with the wealthy UK businessman seeking to maximise profit, the abolition of slavery and child labour.

Where regulation is lax today?

Apple factories with suicide nets in China.

The modern business person chases around the world to find the poorest nation with the laxest regulations so they can exploit these people in the same way they used to exploit the citizens of their own nations two hundred years ago.

Labour costs are reduced to the absolute minimum to maximise profit.

Capitalism in its natural state sucks everything up to the top.

Capitalism in its natural state doesn’t create much demand.

Modern, mainstream economics is a disaster area; it also has two further fundamental flaws in its assumptions:

1) Doesn’t differentiate between “earned” and “unearned” wealth

Adam Smith:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

Like most classical economists he differentiated between “earned” and “unearned” wealth and noted how the wealthy maintained themselves in idleness and luxury via “unearned”, rentier income from their land and capital.

We can no longer see the difference between the productive side of the economy and the unproductive, parasitic, rentier side.

The FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate) sectors now dominate the UK economy and these are actually parasites on the real economy.

Constant rent seeking, parasitic activity from the financial sector.

Siphoning off the “earned” wealth of generation rent to provide “unearned” income for those with more Capital, via BTL.

Housing booms across the world sucking purchasing power from the real economy through high rents and mortgage payments.

Michael Hudson “Killing the Host”

2) Ignores the true nature of money and debt

Debt is just taking money from the future to spend today.

The loan/mortgage is taken out and spent; the repayments come in the future.

Today’s boom is tomorrow’s penury and tomorrow is here.

One of the fundamental flaws in the economists’ models is the way they treat money, they do not understand the very nature of this most basic of fundamentals.

They see it as a medium enabling trade that exists in steady state without being created, destroyed or hoarded by the wealthy.

They see banks as intermediaries where the money of savers is leant out to borrowers.

When you know how money is created and destroyed on bank balance sheets, you can immediately see the problems of banks lending into asset bubbles and how massive amounts of fictitious, asset bubble wealth can disappear over-night.

When you take into account debt and compound interest, you quickly realise how debt can over-whelm the system especially as debt accumulates with those that can least afford it.

a) Those with excess capital invest it and collect interest, dividends and rent.

b) Those with insufficient capital borrow money and pay interest and rent.

Add to this the fact that new money can only be created from new debt and the picture gets worse again.

With this ignorance at the heart of today’s economics, bankers worked out how they could create more and more debt whilst taking no responsibility for it. They invented securitisation and complex financial instruments to package up their debt and sell it on to other suckers (the heart of 2008).

Francis Fukuyama in 1992 said it was “the end of history” and Capitalism had been the only successful economic system to stand the test of time.

Even then work was well under way to turn it upside down.

40 years ago most economists and almost everyone else believed the economy was demand driven and the system naturally trickled up.

Now most economists and almost everyone else believes the economy is supply driven and the system naturally trickles down.

Economics has been turned upside down in the last 40 years.

In the 1960s and 1970s we had some of the lowest levels of inequality in history within the developed world.

The new upside-down economics is driving inequality.

With the old economics, where demand is seen as the driver, reasonable wages are required to keep the economy going.

In those days the US consumer was seen as the engine of the global economy.

The new economics is wiping out the middle class in the US, they are irrelevant.

Should we be looking to get that old successful economics back again before global demand is totally destroyed?