It’s frustrating to see a group that is dedicated to good causes, and has chosen a deserving target, go off the rails in trying to make its case. Worse, like minded individuals who are hungry for backup for their beliefs, and who cite half-baked studies play into a stereotype that the Powers That Be are keen to promote: “Those who deny that we are living in the best of all possible worlds don’t know what they are talking about.”

Today’s object lesson is a report by Oxfam, Extreme Wealth is Not Merited” by Oxfam. Author Didier Jacobs works through some assumptions (more on that shortly) and comes to the implausibly precise estimate that 74% of American billionaires’ wealth comes from rent seeking (oddly, the chart from which you can compute that result is in the webpage summarizing the paper but not the paper proper). And mind you, there are good efforts on this front. Later this week, we’ll discuss a recent paper on inequality that hasn’t gotten the attention it deserves that is much more careful and more important, points to concrete policy measures.

This isn’t the first report by Oxfam on wealth that has been criticized for simplistic-to-the-point-of-being-misleading statistics.

Now of course, it’s not hard to agree that a sizable portion of the current top wealth comes from rent extraction of various sorts, given the correlation in time frames between deregulation, greatly weakened anti-trust enforcement, and the dramatic rise in concentration of wealth and incomes in the US. But just because a piece of work confirms one’s prior beliefs does not mean it’s sound.

This report has such significant conceptual flaws that it’s better to address them than get down in the weeds of lower-level issues.

Estimating how much income or wealth comes from rent extraction is an impossible exercise. Oxfam was beaten before it started. Even if you could get the right data, how do you draw the line between supposedly virtuous profit-seeking versus rent extraction? Let’s start with your cable bill. Some portion of that does represent the actual cost of the service, an adequate return on capital and justifiable profit margin. But even figuring that out is not trivial. And then you need to aggregate that across companies and industries and figure out how that maps into the wealth of the richest.

At a higher level of abstraction, having a business that achieves sustainable profits over time entails creating or exploiting market inefficiencies. Perfectly efficient markets generate thin to no profit. Now creating profitable niches can create wins for the customer, like putting a convenience store on a freeway, where people will pay a ridiculous amount for a soda or a candy bar or gas because the next opportunity is a hundred mile away because they need whatever they need now and accept that running a store in the middle of nowhere doesn’t have the greatest economics even with those high prices. Another example is a fashion designer that creates a particular look that appeals to a group of customers who come to buy clothes from that designer regularly. But most large-scale enterprises benefit from all sorts of subsidies, which raises the question of whether what they give (in terms of price, product/service quality and taxes and fees paid to the government) is fair? It’s doubtful that one can set a clear boundary even in narrow cases.

And even when companies engage in abuses of market power, like requiring customers to sign agreements that have them give up their right to litigate, how do you determine what that is worth in any particular case?

Rentier activity is a lot like pornography: hard to define in a way you can operationalize, but you know it when you see it.

This conundrum illustrates why almost always a bad idea to try to come up with single point estimates of complex phenomena. If you do attempt to put metrics on them, its better to measure what you can measure reasonably well, paramaterize other important issues as best you can, and make qualitative conclusions.

One example of why this exercise is fraught: While the paper shows estimates of what percent of activities of various industries come from rents, the industry definitions are so broad as to be meaningless. What is “finance”? That ranges from useful but somewhat overpriced retail banking to socially useful lending and capital raising to generally excessive secondary market trading (other economic studies have found the resources devoted to trading are to the detriment of economic growth). Yet even though too much in the way of economic resources goes into casino capitalism, it does not follow that your discount brokerage account enables some rent-seeker on the other side (as in “rent-seeking” is a subseet of “socially unproductive” and that might have been the better frame of reference).

Moreover, there are other issues with how “finance” is categorized. The Oxfam report does correctly, based on other research, depict it as heavily subsidized by government. It fails to consider the fact that “finance” has gotten more than occasionally been involved in criminal activity, such as money-laundering and bid rigging (both on mass scales), mortgage and foreclosure fraud, and debt collection abuses.

And the report omits that the biggest winners, in terms of entry into the billionaire’s club, have been hedge fund and private equity fund managers. They enjoy massive tax subsidies, something the report fails to mention.

Now the paper could still have approached this exercise with the modesty that befits what they sought to achieve versus the limited means (data and resources) they had to devote to this exercise. There’s still merit in exercises meant to stimulate more research and debate. But this article reaches conclusions that are far too firm for the nature of the exercise.

The article reinforces the shibboleth of meritocracy. This is simply stunning. Jacobs states the he is putting aside theories of social justice and accepts the framing of Greg Manikw, that “no one objects” when wealth is perceived to have been fairly earned:

My sense is that people are rarely outraged when high incomes go to those who obviously earned them. When we see Steven Spielberg make blockbuster movies, Steve Jobs introduce the iPod, David Letterman crack funny jokes, and J.K. Rowling excite countless young readers with her Harry Potter books, we don’t object to the many millions of dollars they earn in the process

This happens to be a US perspective on this matter. Most of rest of the world does not treat the workings of capitalism or the wealthy with the same reverence as Americans. It’s not hard to understand that many people work hard and have talent, yet only a few stumble into the circumstances that allow for them to earn exceptional, or even very good, incomes.

Mind you, Jacobs is not using meritocracy as a straw man. He astonishingly asserts that the economy operates on a meritocratic basis….except for the really rich (and those stuck in poverty traps:

Market pay does generally reflect talent, effort, and risk-taking—but not at the extremes. For all the imperfections of our market economies and of the government policies that underpin them, middle-class people are roughly compensated on merit: an architect who is marginally better than another is likely to earn marginally more, and likewise for most professions and trade.

In other words, Jacob’s framing does not just unwittingly reinforce “meritocracy” as attainable attainable and desirable. He claims, with no foundation, that many people’s pay reflects what they are worth.

Yet as we discussed at length in a 2006 article in The Conference Board Review, meritocracy is unachievable. It’s a myth that legitimizes disparities in income and status. As we wrote:

The Illusion of Meritocracy

OK, so diversity programs may not serve the people they are designed to help. One of the reasons is that these initiatives are assumed to undermine merit-based hiring and promotion. Indeed, as Barres points out, citing research, “When it comes to bias, it seems that the desire to believe in a meritocracy is so powerful that until a person has experienced sufficient career-harming bias themselves they simply do not believe it exists.” But the idea that an organization can be truly meritocratic is, alas, a fiction.On a practical level, the best a company can hope for is that, taken as a whole, the people it hires and promotes are “better”—as defined by the company—than the people it rejects. On an individual level, the role of luck, combined with inherent shortcomings of performance-appraisal systems, make it impossible to have confidence in the fairness and accuracy of any particular staffing decision….

Now, for most people, it’s well nigh impossible to pick apart the importance of ability versus good fortune. Yet early career decisions and moves often have an arbitrary element (a young person takes a rotation into a new area that takes off, or has a bad run of assignments and gets discouraged) that can influence later career success.

Other factors can thwart an organization’s meritocratic efforts (many of these observations derive from a 1992 paper by Patrick D. Larkey and Jonathan P. Caulkin, “All Above Average and Other Unintended Consequences of Performance Appraisal Systems”). Many people, for instance, run up against conflicts between individual and organizational interests. Implicitly, any employee’s job is to serve his boss, when his check is actually being cut by the company. If the employee views his role as being different than his boss sees it, the boss’s view prevails, whether or not it is correct. In an extreme case, if the boss wants the employee to run personal errands, and the employee refuses, he runs the risk of getting a negative review.

There’s the Peter Principle conundrum that the skill requirements at one level may bear little relationship to the demands of the next. You’ve heard the old chestnut, “Promote your best salesman, and you lose a good salesman and gain a lousy manager.” But this situation puts bosses in a real bind. If you promote the person who is best in a department, his skills may fall woefully short of the requirements of his new role. But if you promote the person you deem best suited for that job, and not the top performer at his current role, you will demoralize his former peers, create resentment against him (undermining his authority and effectiveness), and raise questions about your judgment.

And then there are difficulties in ranking employees across organizational units. Even though organizations want consistent ratings firmwide, it’s a practical impossibility. There are considerable barriers to a manager giving his staff member honest and useful feedback that lead to inflated ratings. They have an ongoing relationship; and thus both sides do not want the review process to create friction. Yet most employees have an inflated view of their achievements, which predisposes them to doubt, perhaps even resent, a truthful appraisal. And since the assessment of a job of any complexity is largely subjective, it’s difficult forthe boss to defend a rating that is at odds with the employee’s self-assessment. In addition, managers consider themselves at least partly responsible for their subordinate’s performance. Thus a low rating reflects badly on them.

The consequences are profound. It means that the typical defense against the failure to achieve diversity, that the company was in fact hiring and promoting based on achievement, is hollow. These systems not only are subjective (inherent to most ratings) but also often lead to capricious, even unfair results.

And there is evidence that subjective processes set a higher bar for minorities and women. For example, a 1997 Nature paper by Christine Wenneras and Agnes Wold, “Nepotism and Gender Bias in Peer-Review,” determined that women seeking research grants need to be 2.5 times more productive than men to receive the same competence score. In 1999, MIT published the results of a five-year, data-driven study that found that female faculty members in its School of Science experienced pervasive discrimination, which operated through “a pattern of powerful but unrecognized assumptions and attitudes that work systematically against female faculty even in the light of obvious good will.”

So here you have the worst of all pos sible worlds. You want to achieve diversity, if for no other reason than to forestall lawsuits and present a better face to your customers. Yet you have long believed the main reason is that you haven’t been able to find enough “talented” members of the various groups to fill out your managerial ranks. But your performance-appraisal system is subjective and probably unreliable, and the complex nature of organizations means that who rises is largely arbitrary, and it is likely that “out” groups are subject to higher performance standards. All this to say that women and minorities’ frustration at their failure to achieve reasonable representation may well be completely justified. Your organization may be guilty as charged.

Mind you, if it is impossible within an organization, even assuming diligent and well-intentioned management, to achieve meritocracy, how can it possibly be a reasonable expectation across society?

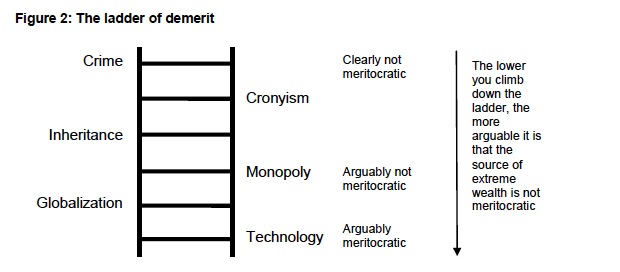

A key analytical framework is hopelessly flawed. This is how Jacobs sets his hierarchy of rent extraction:

First, these categories are analytically sloppy. Even though they include many of the explanations given for inequality, they aren’t even close to a mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive list of opportunities for rent extraction. They are incommensurable. A classic and more obvious example comes from the what is purported to be an ancient Chinese encyclopedia, the Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge, as reported by Jorge Luis Borges. Per Wikipedia:

The list divides all animals into one of 14 categories:

Those that belong to the emperor

Embalmed ones

Those that are trained

Sucking pigs

Mermaids (or Sirens)

Fabulous ones

Stray dogs

Those that are included in this classification

Those that tremble as if they were mad

Innumerable ones

Those drawn with a very fine camel hair brush

Et cetera

Those that have just broken the flower vase

Those that, at a distance, resemble flies

And as we alluded to earlier, that’s before you get to the fact that Jacobs seems to regard criminal activity as only successfully prosecuted criminal activity, like drug dealing or Ponzi schemes.He fails to acknowledge criminal activity that is a meaningful component of the activity or strategy of a company. For instance, Jacobs accepts the Greg Makiw view of Steve Jobs as someone whose wealth was fairly earned. Yet Jobs was at the center of a wage-fixing operation. Price fixing is criminal. In the mid 1990s, five companies were investigated for price fixing in the lysine market, which resulted $105 million in criminal fines and three executives at the company most deeply involved, ADM, going to prison. But this is the new millennium and Silicon Valley icons like Steve Jobs, Eric Schmidt and George Lucas are too famous to jail.

Finally, Jacobs seems to greatly underestimate the degree to which large swathes of “technology” depend on government subsidies. All 12 of the core technologies in the iPhone were developed by the government. Yet Apple goes to great lengths to avoid paying taxes in the US. Similarly, as we’ve mentioned regularly, Big Pharma also benefits from ample government support and R&D tax breaks, yet also shifts profits offshore when they arrive.

The article exhibits a limited understanding of how commerce works. So as to avoid taxing reader patience, here is one illustration:

Economies of scale are a technological reality in all industries: division of labor increases productivity. Some of the lower cost is passed on to consumers; the rest is kept by the company’s owners.

Sweeping and inaccurate generalizations further undermine the credibility of this work. There are plenty of cases where economies of scale do not operate because the increased supervision/coordination costs more than offset whatever benefit is derived from narrowing job tasks. Banking is a classic. Studies have consistently found that banking exhibits an slightly increasing cost curve (as in it shows diseconomies of scale) once a certain size threshold is achieved; the research differs only on where that size level sits.

I wish this discussion were tidier, in that flawed research provides useful grist for critical thinking. But this paper’s weaknesses are so fundamental that it’s hard to talk about them in as crisp a manner as I’d like. The flip side is there is a good deal of solid thinking being done in this area and so there’s no dearth of research that makes a powerful case that we’d all be better served, including the rich*, if their wealth was reined in.

____

* See here for details.

Yes, it is class warfare, and our class isn’t winning.

The Pharaoh, the Court and the Temple bureaucracy get the majority of benefits of mass production (agriculture). We get to die young and get honest burials in the nearest sand-dune. Same as it always has been.

So say we all.

What the author and so many others in the educated elite don’t want to address is that at heart this is a normative, not a technical or empirical, question. “How much is too much?” and “What is a fair return on investment?” are questions of ethics. The stock response to any questioning of the ethics of accumulation and poverty is “who are YOU to say what’s right and wrong?” But as a sentient human being with a moral compass it is exactly me, and all of us, who have to individually and collectively answer these kinds of fundamental questions. It should sound as silly to ask, who I am to question why some have everything and some have nothing, as it is today to ask “Who are YOU to say I can’t steal your car?”.

Clarification: I meant the Oxfam author, not Yves.

Meritocracy is an article of faith in the foundation world. This is reason #1 why the rising influence of “liberal” foundations has coincided with the declining fortunes of working people.

Yes! THIS (LiW’s) is the crucial point, as succinctly stated here and elaborated (twice in 10 years it seems) above by Yves.

It’s what makes the reverence with which “good causes” or an undifferentiated “Charity” are treated in the UK so nauseating.

That and the barely disguised emphasis on the spiritual improvement of the donor rather than the supposed real-world effect of the donation. The words “give” (intransitive!) and “giving” are automatically understood to mean donation to Charity of who-cares-what-kind, with all the moral focus on the conscience of the “giver”.

Telling, too, that the most eager promoters of all this are the same people (individuals/NGOs/local government) who scream loudest against giving money directly to “rough sleepers” (or in the language of the Righteous, human “eyesores”) on the grounds that the panhandlers might spend it on their Bad Life Choices.

London is full of “homelessness charities” concerned with everything but housing, i.e. strictly with the supposed character defects of the individual homeless person. One of them (breathtakingly named: “Crisis”) actually markets itself with the slogan: “We see the person, not the homelessness”.

No surprise then that many of the same organizations (notably Barnardos, whose “character defects” obsession goes back to the 19th century) accept compulsory placements of the unemployed to work for free in their fundraising stores.

Sorta like reducing cosmology to creation mythos… whilst both share basic similarities… the devil is always in the details… yet some wonder why policy formation is such hard yacka these days…

Skippy…. whilst were at it the canons are missing a few authors… so does that skew the data – ?????

Yves correctly summarizes, “… this paper’s weaknesses are so fundamental that it’s hard to talk about them…”

The common fundamental weakness demonstrated here is a lack of balance between competing basic human perspectives…

Origin of Sustainability Movement Leads to Current Challenges

http://www.triplepundit.com/2010/08/origin-of-sustainability-movement-leads-to-current-challenges/

How Do We Develop a Sustainable Civilization?

http://www.triplepundit.com/2010/10/achieving-sustainable-land-development/

I agree balance is important, but I think what this effort primarily demonstrates is the unwillingness to follow evidence to a conclusion. The author assumes that merit exists in the labor force, for example, rather than examining actual labor practices and then analyzing the situation.

Software development is another industry that does not benefit from economies of.scale.

Humanity is still struggling to find its place in the world. A perspective of who and what we are in our relationship to the universe. As a collective society, we have replaced one delusion with another- the belief in Gods directing the world with one of free markets determining the proper outcomes for all human relations. Its like the priests of one order shifted over into another order and just tweaked the language for the ignorant masses to adapt to new circumstances. Knowledge does progress and the old stories loose potency to control social action.

In the end we are left with an ethical choice. Will we treat the people around us, and who live with us kindly or will we treat them with distain. Right now, we are collectively in the muddled middle ground. Collectively, we cannot decide on a clear choice. Either way, this choice illustrates that social relations are organized and planned by the individuals who make up that group- not some divine intervention whatever the source.

Complex world indeed.

We are not in any middle ground. Some of us are on one side; some of us are on the other. You cannot just average this out.

The problem for both sides isn’t that we can’t come to a compromise. It’s that we can’t separate the two, allowing each to go off and try, undisturbed by the other, what each believes is right.

I think you are correct, Benedict, in observing that the problem (or, one problem) is that we can’t come to a compromise. As the nation could not come to a compromise over the ‘morality’ of buying and selling humans. And, look where that got us!

I participated in a discussion group on Saturday, where the leader stated that Marx would not have considered hedge fund managers, and their ilk, to be evil people. They are simply caught in a system that rewards them for acting in this way. Not to argue with his interpretation of Marx, whom I cannot read without experiencing instant brain freeze, but I countered with the argument that unless society made it clear that the activities of hedge fund managers were unacceptable and that anyone doing this job was morally impaired (as we now consider anyone who engages in outright slave-trading), we would never succeed in changing the system.

But, as you rightly point out, our nation (world?) is rapidly breaking down into two adamant groups, with radically different views of what constitutes a wholesome society. Before we get from here to there, it may get messy.

It’s God’s will.

If God wanted you to be rich, he would have provided you with a character like Bill Gates/Clinton.

The tiny percentage of folks at the top are marinated in an ideology that allows/encourages the perspective that they alone possess the ultimate virtues of our ‘culture’, and that it is this clear-headed virtue that has resulted in their wealth.

One of the top-dogs in the organization for which I work, once told me quite enthusiastically that he had been reading Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged, and that the book accurately portrayed “exactly what is happening now!”.

This man is responsible for building and maintaining our organization’s many facilities, and in this capacity, deals with what he considers to be “excessive regulation“, which when properly considered means any regulation at all.

Proper consideration means in this case, understanding that local governments are so business friendly, that they routinely bend over backwards to please anyone who promises jobs for their locality, which includes doing everything they can to blunt the impact of any regulations that businesses tell them impact their decisions, like where, and what you’re allowed to build.

In a certain, important sense what this man was doing when he explained his enthusiasm for Ayn Rand’s work, was defining a perspective that I was required to agree with, whole-heartedly, or risk losing ‘credibility’ within the organization.

On another occasion, my boss, explained to me that a certain important group of his employees pay plan allowed them to attain $35/hour, by virtue of hard work, and possession of the proper skills.

His clear expectation was that I applaud his magnanimous attitude, and fair treatment of ‘our‘ people.

The trouble with this picture is I’ve known many of these people for twenty years or more and, I know that there’s not one of them who attains more than $25/hour under their ‘merit-based’ pay plan.

The top dogs in our country live in a bubble where they all agree, (it’s required), that they are set-upon on all sides by hostile forces with unreasonable demands that must be resisted at all costs.

This resistance is deemed a ‘virtue‘, and the ‘virtuous‘ earn God’s favor.

It comes down to this then, you will have religion, it will be our religion.

Who are you to argue with God?

+1

But you need to change the “It’s God’s will” into “It’s the Market’s will”.

Of course the people in the Robes/Suits know God’s/Market’s will. They are devinely meritorious. Soothsayers extraordinaire. AI wired into the eternal chorus.

But anyone can also play GOD MOD. Hence, why are the people who do the actual work becoming poorer?

The Market Wills It.

The author commits the additional absurdity of equating market success with merit. In what moral universe does a Steven Spielberg or a David Letterman(!) — using Jacobs’ own examples — “deserve” vast wealth, notably under-taxed, as well?

It should be sufficient at Oxfam to note that an entertainment economy provides preposterous returns for a tiny few; the organization is not obliged to celebrate the mechanism and praise the winners.

Awesome takedown.

I rather enjoy the specific irony that the list of people who earned their wealth 1) doesn’t comprise the very richest of the rich, and 2) depends upon IP law in particular. That is government subsidy in one of its purest forms.

More generally, it is good to see someone’s assumptions so clearly spelled out. Economic language is usually vague and noncommittal, with unstated assumptions, because once you state something plainly, like people’s wages generally reflect the talent and effort involved, the absurdity is overwhelming.

Wow, so that is what “Jacob’s Ladder” looks like!

I’m not clear about why ‘rent seeking’ is bad. Or why ‘meritocracy’ is good.

I agree with John Bates Clark that there is no such thing as unearned income.

Meritocracy was examined by Christopher Lasch in his book ‘The Revolt of the Elites and the Betrayal of Democracy,’ (1992), and by Charles Murray in ‘Coming Apart,’ (2012). Both of them thought it an awful development, which hollowed out the working class by drawing away their best and brightest with money.

This is an important topic. Yves writes:

But as a forcing device for discussion: What if you can’t, and not because the object of inquiry poses analytical challenges, but because it does not exist?

“Actual cost,” when broken down into its component line items, is fractal: It will surely include rents (like, at a cable company, IP on technology). And so too the line items for that line item…. And how does one construct a rent-free yardstick for “adequate” and “justifiable”?

Maybe it’s just power-imbalances all the way down….

From a recent post at Economist’s View:

“Drawing on state administrative records for millions of individual Americans and their employers from 1990 to 2011, John Abowd and co-authors have estimated how far individual skills influence earnings in particular industries. They find that people working in the securities industry (which includes investment banks and hedge funds) earn 26 percent more, regardless of skill. Those working in legal services get a 23 percent pay raise. These are among the two industries with the highest levels of “gratuitous pay”—pay in excess of skill (or “rents” in the economics literature). At the other end of the spectrum, people working in eating and drinking establishments earn 40 percent below their skill level. …”

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2016/03/make-elites-compete-why-the-1-earn-so-much-and-what-to-do-about-it.html

Perhaps a somewhat better quality paper than the Oxfam one – though I confess I have only read that post.

I skimmed the string and unless I missed a comment, no one stated the obvious.

Wealth is a gift from nature and the collective labor of humankind, and, I guess, animals too.

No one person’s contribution counts for more than does a drop of water for existence of the oceans.

I suppose it is useful to separate productive from unproductive labor and parse the rewards due to each person.

But such an effort is not necessary. Anyone with a billion dollars is the recipient of wealth that was socially created, whether stolen as a rentier or bundled from the productive labor of others.

I am having a hard time understanding the “takedown” of Jacobs. Nothing Yves said undermines the argument being made in the paper (although you have to get past the introduction to see why in some cases). In the interest of brevity, I will skip past everything but the Meritocracy assumption because this is Yves main complaint.

The paper is going after a particular argument for why billionaires are justified in having so much wealth (relatively speaking)… it was earned by virtue of their actions (the meritocracy argument). So, all the paper has to do is show that some/most of billionaire wealth is not derived from the talent, effort, or risk-taking of the billionaire and therefore cannot be justified on meritocratic grounds.

I appears that Yves thinks that provisional acceptance of Meritocracy already concedes too much. She is correct in noting that women and minorities are discriminated against and/or held to higher standards. That behavior is hardly becoming of a meritocratic society. And, I think, she considers an ideal meritocracy to be both impossible and unhelpful in informing “real” decisions. Thats fine. Rational people can disagree on this point (see Rawls vs Sen on a similar scenario).

Taking the dismissal approach to beliefs about meritocracy, however, is generally only persuasive to those already on your side. As long as the discussion is based on whether or not we should accept a meritocratic conception of society, the billionaires can keep extraction going because there can be legitimate disagreement.

However, if extreme wealth can be shown to be unjustified –by the very principles being espoused by meritocracy proponents– then it forces the billionaires to change justifications or lose some of the political support they enjoy. At a minimum, then, if you agree with the conclusion the paper makes (extreme relative wealth is not justified), you should want to be very clear about just where you disagree. While I won’t win any popularity for saying this, Yves rant was not clear.

Here is my response to Yves’ criticism of my blog and the underlying paper.

Estimating how much income or wealth comes from rent extraction is an impossible exercise. Right, I acknowledge as much in the blog. My estimate of 74% of the US billionaire wealth being rent must of course be taken as a back-of-the-envelope estimate. I quote at the beginning of the blog a couple of studies that support each side of the question I ask – are billionaires fat cats or deserving entrepreneurs? Given this stalemate, a back-of-the-envelope estimate is better than no information at all. My conclusion that extreme wealth is not broad-based but concentrated in industries that happen to be known for rent-seeking is sound. It is a conclusion that becomes increasingly mainstream, as evidenced by last week’s issue of The Economist magazine, for instance: http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21695392-big-firms-united-states-have-never-had-it-so-good-time-more-competition-problem

The article reinforces the shibboleth of meritocracy. Smith reads me wrong. My paper makes it clear that the reason why I discuss meritocracy is that it is the main argument of the defenders of extreme wealth. In the introduction of my paper, I clearly explain why many philosophers find meritocracy a flawed concept. I also write that it would be easier to attack extreme wealth from the perspective of other theories of social justice. And I clearly state that:

“Although Oxfam does not have an official position on which of these philosophical schools of thought it supports, Oxfam consistently advocates for a society that is constructed with the interests of the poorest and the most marginalized at its heart, which would suggest a preference for egalitarian liberalism. Certainly by exploring the internal strength of meritocracy as a defense of extreme wealth, this paper is in no way endorsing meritocracy as the primary source of moral value.”

A key analytical framework is hopelessly flawed. This point is not convincing. The logic behind the framework is to rank certain sources of wealth according to the extent to which they can be considered as contributions to society, which is the definition of meritocracy.

Each element of my analytical framework is defined with sufficient rigor to determine whether it applies to each billionaire or not. True, the six elements are not mutually exclusive, but I do take out double-counting from the total. I believe that the six elements are collectively exhaustive, and Smith does not provide any counter-example.

On criminality, everyone ought to be considered innocent until proven guilty. However, I clearly state that my definition of cronyism also involves crime that goes unpunished because of state protection.

On technology, the points Smith makes belong to my cronyism and monopoly sections, and I also discuss them in the appendix on intellectual property.

The article exhibits a limited understanding of how commerce works. This critique is unfair. I have written this piece for people not trained in economics, implying some vulgarization, but not to the point of disinformation.

Even in the one example Smith provides – economies of scale in banking – she acknowledges that diseconomies of scale kick in only beyond a certain threshold.

Two responses:

1) On Meritocracy, Jacobs comments:

But Jacobs writes:

I don’t see any other way to read the above than “reinforcing the shibboleth of meritocracy,” which applies just as much to the upper crust of the credentialled classes as it does to the rich. (Are we really to believe that all eight current Supreme Court justices are from Harvard or Yale based solely on merit?)

2) ) A key analytical framework is hopelessly flawed/ First, if the framework isn’t mutually exclusive, as Jacobs admits it is not, then it’s hopelessly flawed, as a framework, by definition, no matter what post-processing is applies to its results (i.e., avoiding doublecounting). Second, Jacobs writes “I believe that the six elements are collectively exhaustive, and Smith does not provide any counter-example.” First, with categories so vague and capacious as “Globalization,” it’s almost a foregone conclusion that the categories would not be “collectively exhaustive.” Second, I can think of at least two ways of accumulating great wealth that seem to merit their own categories. First, kleptocracy, not in the generic sense that the ruling class is shot through with thieves, but with examples like Malaysia’s Najib or Haiti’s Papa Doc in mind (and if this is to be filed under “Crime,” see above on vague and capacious categories). A second would be speculation. Again, one could try to fit, say, Soros, under “Globalization,” but that seems to do violence to the category. What would not be “Globalization,” in such a case?