You can tell things are going a bit pear-shaped when single stories in the business press are so meaty as to warrant posts all on their own.

Today’s example is a Financial Times story, Oil and gas: Debt fears flare up, which gives a grim update on the wreckage in the wake of the energy price collapse, and how the damage to lenders has only started to play out.

None of the underlying themes will be new to readers. We’ve been warning for some time, first of the froth in the junk bond market, and its particularly high exposure to energy concerns, and then the correction last year. We were also one of the few to argue that the “cheap gas will prop up the economy” would be offset, and likely more than offset, by the losses of high-paying oil and shale gas jobs and the impact of direct (energy company) and indirect (real estate loans in oil boom areas) lending losses on banks and investors. We further stressed that the energy price rebound was not going to happen in a mere six months, as was the almost universal consensus in early 2015, because shale gas players had strong incentives to keep pumping until their money sources cut them off. Indeed, while we recognized that issue (identified by the Financial Times’ John Dizard) as a key driver that was widely ignored, if anything, we underestimated that an analogous set of imperatives – the need to fund national budgets – would also lead energy producing nations to maintain production levels even at what they would have recently regarded as depressed prices.

But what is new, and important, about the Financial Times article, is its effort to put parameters on the severity of the slump and how bad the collateral damage might be, particularly to financial players. Even though Mr. Market is feeling his spring oats, let us not forget that back in January, one of the causes for concern was European banks. It was widely recognized that on top of existing bad loans, the Eurobanks collectively were sitting on an estimated additional $100 billion in energy-related losses. Indeed, the pink paper addresses that concern by mentioning how Crédit Agricole, with the second largest energy debt exposure on the Continent, had to reassure investors, telling them 84% of its book was investment grade.

It’s also worth remembering that the recent oil rally is unlikely to be a harbinger of more price appreciation soon. Stockpiles and oversupply remain large. Even the generally upbeat OilPrice warned yesterday that the market was driven lately by sentiment more than fundamentals.

I strongly urge you to read the Financial Times account in full. Key points:

Distress in the oil and gas industry is acute. Many companies are being liquidated or forced to cut to the bone:

About 600 people packed on to the Machinery Auctioneers lot on the outskirts of San Antonio, Texas, last week to pick up some of the pieces shaken loose by the oil crash.

Trucks, trailers, earth movers and other machines used in the nearby Eagle Ford shale formation were sold at rock-bottom prices. One lucky bargain hunter was able to pick up a flatbed truck for moving drilling rigs — worth about $400,000 new — for just $65,000.

Since the decline in oil prices began in mid-2014, activity in the Eagle Ford, one of the heartlands of the shale revolution, has slowed sharply. The number of rigs drilling for oil has dropped from a peak of 214 to 37, and businesses, from small “mom and pop” service providers to venture capital companies, are trying to offload unused equipment.

Terry Dickerson, Machinery Auctioneers’ founder, says sales doubled last year, in part thanks to the oil crash. Sellers are sometimes disappointed by low prices for oil-related assets, but they have to accept reality, he says. “I feel like a funeral director,” he adds. “I’m the one that has to tell them the bad news.”

Lenders went on a spree. While this is a notoriously cyclical industry, the shale gas frenzy drew in a lot of newbies, particularly among investors. The fact that so many players made heavy use of borrowings, with the Fed’s negative real interest rate policies all too successfully pushing lenders into risky assets, has amplified the damage. From the story:

From 2006 to 2014, the global oil and gas industry’s debts almost tripled, from about $1.1tn to $3tn, according to the Bank for International Settlements. The smaller and midsized companies that led the US shale boom and large state-controlled groups in emerging economies were particularly enthusiastic about taking on additional debt.

The hangover has only just begun:

Standard & Poor’s, the credit rating agency, assesses oil companies based on an assumption of an average crude price of $40 this year. On that basis, 40 per cent of the US production and oilfield services companies it covers are rated B-minus or below. “B-minus is a very weak rating,” says Thomas Watters of S&P. “You don’t have a long lifeline.”

Make no bones about it: a B- or worse means you are barely hanging on. To illustrate:

Linn Energy, one of the 20 largest US oil and gas producers, warned last week that it expected to breach its debt covenants. It has net debts of $3.6bn, but only $1m in borrowing capacity. Many US producers are now having their borrowing limits, which are based on the value of their reserves, redetermined by their banks. The falling value of those reserves means loan facilities will be cut back, leaving some companies without enough liquidity to stay afloat.

Even when companies can be restructured, lenders are taking big hits:

When oil and gas companies go into bankruptcy, there are often slim pickings for creditors. Quicksilver Resources, a Texas-based gas producer, went into Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection last year with about $2.4bn of debt. This year it announced sales of its US assets for just $245m, and some of its Canadian assets for $79m. Its creditors are on course for losses of about $2bn.

Do the math. That’s an 83% loss of principal. The story reassuringly points out that even bigger amounts are at risk at national oil companies like PDVSA of Venezuela and Petrobras.

In a worrisome parallel to subprime risk before the crisis, investors are getting rattled by banks increasing their forecasts of losses:

“It’s alarming that things [bank loan loss estimates are getting pulled forward so much,” says Julie Solar, an analyst at Fitch Ratings. “The pace of deterioration is coming quicker than what was previously disclosed.”…

Since crude prices began to fall in the summer of 2014, investors in oil and gas companies have lost more than $150bn in the value of their bonds, and more than $2tn in the value of their equities, according to FT calculations.

The grim reaper tone of the article suggests that things will get worse in energy-land before they get better. The oil bust in 1980-1981, which was a regional affair in the US, was bloody and took down pretty much all of the Texas banking industry. It’s hard to know from this far a remove what the trajectory will look like, particularly since even with things his visibly dire, the incumbents all have strong incentives to make things appear less bad than they are. Any reader intelligence would be very welcome.

every real man wants to keep drilling until the money runs out. And if you can’t keep drilling, you have to find a new hole. That’s what they say. Some holes cost more than others, but a real man needs a hole. What does a man do now, when his hole is dry and he can’t drill? Or if drilling doesn’t get him where it used to? Those were the days, when a man could drill around and have it be good every time. Each real man has to face the day when just showing up with his drill doesn’t work anymore. He better hope the hole he has is good. And he better not have drilled on borrowed cash, because once a hole is dry for a man there’s no going back to the good times, that’s for sure.

My dad got stuck into KYN, a high yield energy-related MLP back in 2011 – considered suitable for IRAs.

The dividend got its first 16% haircut in Dec. The div was maintained in Q1 2016. But when I took a cursory glance at the financial statements of the top five holdings that comprised 48% of this MLP, this is what I uncovered:

Collectively, these 5 companies had a combined net income of ~40m and ended 2015 with 849m in cash. One of these companies had a negative (~ -1.5b) net income. Collectively, they paid out ~13b in dividends in 2015. The funding of those 13b in dividends was largely accomplished through ~17b in financing activities, via issuing debt and selling stock. Needless to say, they are all heavily in debt and the financing activities doesn’t even address financing interest expenses and the like.

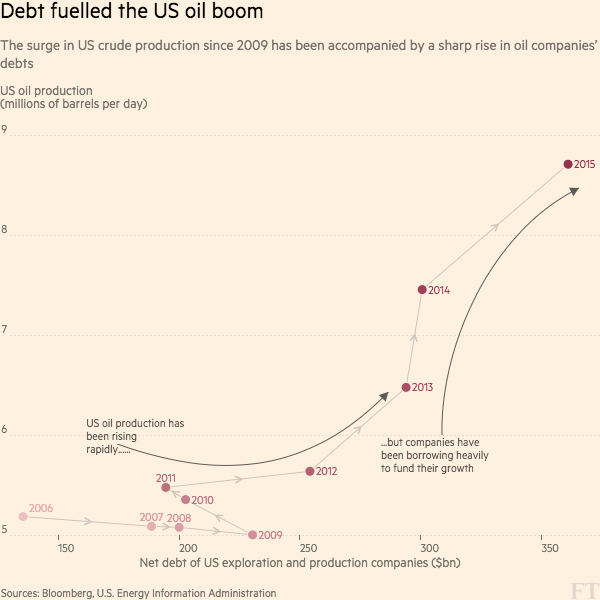

The reason I mention the above is to cite the caption “companies have borrowed heavily to fund their growth” in the EIA chart above as a gross mis-characterization. Their financing activities were funding their dividends in 2015, and without access to the same funding channels in 2016, not only will the divs l be zeroed out – they will all be fighting for survival with little cash cushion and little net income to see them through to another day.

Maybe we could use the high yield to buy Credit Default Swaps on the high-yield fund and retire on those?

Peabody Energy is going tits-up. Similar story, gorged itself on roid’s in the form of cheap debt to fuel “growth” and now all of that bulk is pulling it down the drain. A -800% return on the stock in last 4 years. Impressive. Almost 99 % yield on the unsecured bonds. Chapter 11 seems to be priced in.

From what I’ve read, the investment arms of banks have been busy issuing new stocks and bonds in energy companies with bad loans on the parent bank’s books. The proceeds go to repay these outstanding bank loans, mitigating some or all the damage banks face. What’s left will be largely unsecured loans that the banks could care less about since they belong to some other sucker. Of course the stocks when issued have declined sharply in price thus burning shareholders as well. It appears banks may have learned their lesson from previous meltdowns by farming out the losses.

I wish I could understand how that works. To the best of my knowledge the company itself issues the stocks, I guess I don’t understand how a bank can issue stocks in a company’s name. The same confusion with bonds. I know someone has to underwrite bonds, but doesn’t that leave the underwriter on the hook ??

“One lucky bargain hunter was able to pick up a flatbed truck for moving drilling rigs — worth about $400,000 new — for just $65,000.”

Lucky? @15 cents vs new? 86′ the bottom fishing was at 9% or less – sold in many cases by the pound

The First Liens of the Banks are seriously underwater especially in Canada. The surge in oil prices and the associated refinancing of bonds and secondary stock offerings will get some high profile company exposure off the books of the banks as they take the liquidity for a pay down – but the decline will last far beyond the momentary manipulation.

This exposure extends well beyond oil and gas to all natural resources worldwide – in 86′ the problem was isolated. The previous five years had interest rates for Treasuries north of 9% – in fact deep double digits by 85′ – so the cancer of debt issuance was more limited for that reason plus Junk Bonds 82′ to 85′ were in their market infancy and so were the Commercial Banks acceptance since the Investment Banks were unrelated entities.

This debacle will prove the integrity of the principles of Glass Steagall between Commercial and Investment Banking are absolutely necessary as the separation of Church and State.

‘The grim reaper tone of the article suggests that things will get worse in energy-land before they get better.’

It’s often the case that “grim reaper” articles from the MSM mark important inflection points.

BofA Merrill Lynch’s High Yield spread (over Treasuries) has receded from 8.87 percent on Feb. 11th to 6.65 percent yesterday. FRED chart:

Merrill Lynch’s junk index includes all corporate sectors. But energy is the most troubled, and arguably the driver of the spread.

April crude is at $39.91 this morning, just under the magic $40 lower bound. Translation:

Oops, that’s a stale quote — April crude expired yesterday.

May crude (CLK6) is at $41.35. Chart:

Supposedly smart insiders like banks also caught the falling safe of the subprime market by buying mortgage servicers in the supposed bottom of January 2007.

I think Haygood’s on the right track here.

Everything in the FT piece is true, and it’s a useful read. But there’s a problem with the timing. This thing is likely to go into the books alongside the famous Business Week cover story on “The Death of Equities”.

Two things about oil: First, the glut is not as big as you think. IMO games are being played – in effect painting the tape with big imports that show up in US storage (where the reporting is most transparent) and are hyped by players with agendas. More important, there are 10 – 15 people in the world who can collectively decide – within broad limits – where oil should trade. They can’t put it back at $100 – not right away, not this year – but they can pop it $20 from here with no trouble at all. That will happen soon, because they need it to.

If you’re feeling lucky you can rummage through that pile of junk debt, and find yourself an issuer that might not go bankrupt. Then buy the bonds – not the stock.

Problem with the timing maybe? maybe. A relatively mild winter likely exacerbated the glut, but coming into the summer driving season you can bet there’s some hopes pinned on rallies in gasoline consumption.

Readers, I know (perhaps better than anyone) how addictive the horse race can be… But this is a very important post.

If a man lives by drilling from bed to bed on borrowed cash, it’s not likely to end well. A real man knows when the holes runs dry to him and the cash is gone it’s time to hit the road — because the bed don’t work no more.

If you’re a man who lent money to a man who’s hole’s ran dry and has nowhere to drill, and not even a bed, then it’s time for you to look in the mirror and see the way a real man sees. The way a cowboy looks at the blue sky, out from under the shade of his hat, and thinks about God.

Honest stupid question: so if a bunch of oil drillers and the bankers/investors who funded them go belly up, what does that mean for the rest of us?

it means there’ll be a lot of holes open to drills that still have cash to spend. If your drill is tired, you can upgrade to a huge new drill and a truck for next to nothing and drive around hoping to get lucky. But if you do, make sure it’s a hole you want to live with, because it might dry up on you and your drill may lose its juice. When it does, you won’t want to hit the road anymore. That’s a game for a man with a drill that’s just getting going.

At the very least, it means many people with high-paying jobs going on unemployment, a lot of areas whose real estate prices rose seeing them fall, and a lot of loans not being made as credit dries up as banks try to meet their reserve obligations as they write off the loses. At worst, it means another round of bank bail-outs and even greater political anger and strife here in the home of fracking, the good old US of A.

It also begins to roll over everyone more indirectly. My landlord works in the O&G industry. He’s been unemployed since last June. When my lease expires, there’s a good chance rent will increase or he might choose to move back into this house to keep his own housing costs down. If that happens, the blast radius of unaffordable housing that pushed families like mine out of the metro areas where we work makes the prospect of staying in the state untenable. What trickles down is not prosperity.

That’s an important point. Texas absorbed quite a few refugess from the ’08 crisis.

“Honest stupid question: so if a bunch of oil drillers and the bankers/investors who funded them go belly up, what does that mean for the rest of us?”

some random things—FDIC fund dries up. your local auto parts factory starts laying off people cuz Texans aren’t buying $50,000 pick-ups anymore.

Banks tighten lending standards. Your state’s teachers’ pension fund falls further behind cuz it had investments in “can’t lose” oil deals.

Basically once again the middle class bails out the “smart money.”

The problem I have with this is that it’s a near-certainty that it was Central Banks that intervened directly (or indirectly through their ‘clients’, i.e., the banks) in oil futures as the key to driving both oil (50% rally) and ‘risk’ assets generally off their earlier lows this year. I’ve read that US banks have been encouraged to seek asset sales rather than bankruptcies and to generally cut as much slack as possible to US shale companies by the Dallas Fed, while in Canada banks remain adamant that their exposure in the tar sands is ‘contained’ (which I do not believe they could claim absent a de facto pledge from the BoC)

Now, it would not surprise me at all if oil, stocks and HY bonds took another dive for the simple reason of ‘too much, too fast’ without enough fundamental economic data to sustain a move higher. But any move too low will be met with the same CB action again. So from the perspective of Wall Street, trading oil, stock, bonds etc. in a range that falls short of new highs (for stocks) but not so low as to trigger bankruptcies would make sense until greater clarity is forthcoming from the Saudis, Russia, GCC etc. as to production cut-backs – OR – the political situation in the US becomes such that the prospect of an ugly oil-bust unwind is seized upon by Wall Street and the Fed as insurance against the US voter making the ‘wrong’ choice, and the whole thing is brought down upon the utterly clueless politicians who instantly hand all authority to act right back to the institutions that again caused the problem.

Longer term though, I note Canada’s new Budget calls for 2% growth in Q4 (from 0% in Q1). I cannot imagine getting there without oil prices later this year at least at $50, maybe more. While European banks’ exposures have their own sources and problems, I would be very surprised if, at the end of the day, both US shale and Canadian tar sand production don’t both survive due to Government supports. Ditto Russia. In other words, there are too many interests now aligned for supporting oil, not taking it down – unless as the itchy trigger-finger to deliberately ignite another banking crisis.

Markets no longer function at all with essentially constant support from Central Banks and ‘willing to do whatever’ Governments. Fundamentals like supply, demand, price etc., no longer drive outcomes.

“banks have been encouraged to cut as much slack as possible to US shale companies by the Dallas Fed”

Well, you can see why. The Texas index hasn’t hit bottom yet:

Indeed, the lads in Dallas are so depressed they haven’t got round to updating it since January. They don’t even get out of bed when front-month crude is under $40.

Didn’t mean to discount how hard shale has been hit, just that I don’t think the US will allow shale oil as an industry to fail – just consolidate. Oil power (unfortunately, in my view) has no intention of leaving quietly.

The shale oil industry is a short lived and finite resource. The wells draw down quickly and many will never be economical during the well’s life. It is a bottom of the barrel play. Some say under the barrel. The recoverable reserves have been way over estimated by those with skin in the game. It isn’t a 20 or 30 year supply. It is a few years at best with a price of $70+/bbl oil. Further government subsidies would be gross misappropriation of public funds.

– Some say under the barrel.

I have environmental specialties in hazardous materials management and water resources. Fracking hits both of these, and to me is like someone puking in the punchbowl.

Under the barrel. Well said.

US shale production does not have to all be produced at once – the industry can consolidate its positions and produce in a much more rational, controlled manner for a lot longer. The US could slow production from 9 million b/d to 7 million and be able to do so for years, maintaining a sort of price ‘cap’.

Does this mean I will hear less crap from solar energy doubters? HMMM? Tick Tock fossil fuels, Tick Tock. Dies Irae is nigh.

Plenty of this is priced into capital markets. For example Linn Energy debt trades bellow $10 already estimating recovery. The loan market as well. I’ll guess banks are slower to account for private lending but there’s been some disclosure and more to come, which should be interesting.