Yves here. This paper is more thoughtful and nuanced that its headline might lead you to believe. Nevertheless, there are some additional issues that it does not address.

First is that it ignore the elephant in the room: that Germany is committed to deflationary policies and even worse, is not backing the measures needed to move to Eurozone-wide bank deposit scheme or a viable resolution mechanism. We’ve highlighted some very informative posts by Thomas Fazi which discusses the flaws at length. And even more alarming is that the banking union headfake measures and the proposed sovereign bail in regime both make the EU more, not less, crisis-prone. That’s before you get to the fact that the refugee crisis has good odds of producing political fractures, starting with a Brexit (yes, a Brexit is not the same as an EU member exit, but it raises the specter that that is viable, and makes Marine Le Pen’s threat to depart appear more viable). So as much as the authors can claim that more muscular European banks would be a good thing for Europe, banking policies are even more hostile to that aim than this article indicates. And that’s before you get to the fact that deflation is destructive to banks, even though the ECB has tried to construct negative interest rate policies that limit the damage.

Second, the article fails to consider that the real issue is not who dominates investment banking services, but whether having as much market-based credit (as in securitized credit traded in capital markets, as opposed to bank lending) is a good thing. The evidence suggests not. The ostensible advantage of cheaper credit due to vastly reduced use of “costly” bank equity is offset by more frequent and severe crises, at least in part due to bad incentives. Worse, in the post-crisis phase, as we saw in the US (but was effectively covered up by the authorities), banks needed and got a second bailout, for their mortgage securitization and resulting foreclosure fraud crises. Securitization creates poor incentives and the complexity and rigidity of the securitization structures, compounded the propensity for servicers to be high-volume, highly routinized operations makes it well nigh impossible to restructure loans gone sour, which is the best solution not just for borrowers and lenders, but also for the economy as a whole. Yet the article fails to consider that one of the most important reasons to try to maintain European-based firms would be for Europe to choose its own destiny as far as securitization is concerned, and adopt different models, including rejecting the assumption that cheaper, market-based credit is every and always better.

By Charles A.E. Goodhart, Emeritus Professor in the Financial Markets Group, London School of Economics and Dirk Schoenmaker, Professor of Banking and Finance at the Rotterdam School of Management. Originally published at VoxEU

Europe’s banks are in retreat from playing a global investment banking role. This should not be a surprise. It is an often intended consequence of the regulatory impositions of recent years, notably of the ring-fencing requirements of the Vickers Report (2011) and the ban on proprietary trading by Liikanen (2012), but also including the enhanced capital requirements on trading books and other measures. The main concern has been that a medium-sized European country such as the UK or Switzerland or even a larger country like Germany, let alone a tiny country like Iceland or Ireland, would find a global investment bank to be too large and too dangerous to support, should it get into trouble.1 So, one of the intentions of the new set of regulations was to rein back the scale of European investment banking to a more supportable level.

European banks in the global investment banking scene

The EU, of course, has a much larger scale than its individual member countries. If the key issue is the relative scale of the global (investment) bank and state that might have to support it, could a Europe-based global investment bank be possible? We doubt it, primarily because the EU is not a state. It does not have sufficient fiscal competence. Even with the European banking union and European Stability Mechanism, the limits to the mutualisation of losses, e.g. via deposit insurance, mean that the bulk of the losses would still fall on the home country. Moreover, there would be intense rivalry over which country should be its home country, and concerns about state aid and the establishment of a monopolistic institution. While the further unification of the Eurozone might, in due course, allow a Europe-based global investment bank to emerge endogenously, we do not expect it over the next half-decade or so.

So the withdrawal of European banks from a global investment banking role is likely to continue. That will leave the five US ‘bulge-bracket’ banks (Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan, Citigroup, and Bank of America Merrill Lynch) as the sole global investment banks left standing. The most likely result is a four-tier investment banking system.

The first tier will consist of these five US global giants. The second tier will consist of strong regional players, such as Deutsche Bank, Barclays, and Rothschild in Europe and CITIC in the Asia-Pacific region. HSBC is in between, with both European and Asia-Pacific roots. The third tier consists of the national banks’ investment banking arms. They will service (most of) the investment banking needs of their own corporates and public sector bodies, except in the case of the very biggest and most international institutions (which will want global support from the US banks) or in cases of complex, specialist advice. Examples of this third tier are Australian and Canadian banks, which support their own corporates and public sector bodies without extending into global investment banking. The fourth tier consists of small, specialist, advisory, and wealth management boutiques.

Why should it matter if in all the European countries the local banks’ investment banking activities should retrench to this more limited local role? After all, there are few claims that Australia and Canada have somehow lost out by not participating in global investment banking. We review the arguments further in the column. We also investigate the development of the relative market shares of US and European investment banks in Europe. It appears that the US investment banks are about to surpass their European counterparts in the European investment banking market. We discuss the policy implications in our concluding remarks.

The rise of US and decline of European investment banks in Europe

While the US investment banks are the global leaders, what is their share in the European investment banking market? The Thomson Reuters investment bank league tables rank investment banks by market share. These tables typically cover four major segments: M&A, equity, bonds, and loans (i.e. syndicated loans). We have calculated the weighted average of investment banking proceeds of the top 20 players across these four segments for Europe (i.e. the market share in each segment is weighted by the relative size of that market segment in total investment banking business). Global data are usually split into Americas, EMEA (Europe, Middle East, and Africa), Asia-Pacific and Japan, but we have only EMEA data. However, Europe comprises the vast majority of EMEA investment banking. Data are taken from Thomson Reuters and cover the period from 2005 to 2015 (see, for example, Thomson Reuters 2016). To select the top 20, we take the 11-year average across all investment banks, and use that ranking for all years.

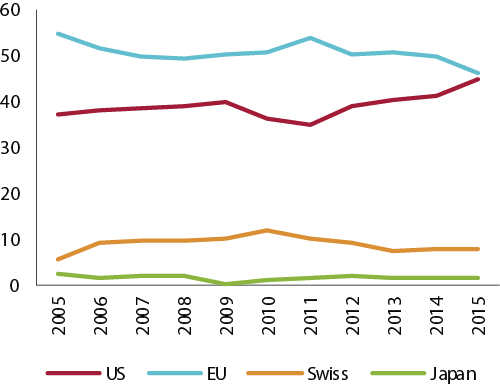

Figure 1 summarises the results (Goodhart and Schoenmaker 2016). The market share of EU and Swiss investment banks has declined since 2010/11, while the share of US investment banks (the big five and Lazards) increased from 35% in 2011 to 45% in 2015. It should be noted that the evolution of the regional market shares reflects partly the broader banking crisis dynamics. US investment banks were the first to be hit in the Global Crisis and declined from 40% in 2009 to 35% in 2011, but recovered after the decisive recapitalisation exercise enforced by the US Treasury. The Swiss decline set in in 2010 and the EU decline in 2011. However, the European share of the investment banking market remains significant.

Nevertheless, Figure 1 shows an underlying structural trend, whereby EU and Swiss investment banks are downsizing. If the trend were to continue, US investment banks would take the prime spot from their EU counterparts soon, possibly already in 2016.

Figure 1. Investment banks by origin, EMEA market shares (%)

Source: Goodhart and Schoenmaker (2016)

Concerns for Europe

We now turn to the consequences of the rise of US investment banks and the decline of their European counterparts. Why should it matter if in all the European countries, the local banks’ investment banking roles retrench to a more limited local role? After all, there are few claims that Australia and Canada, which are largely served by local banks, have somehow lost out by not participating in global investment banking.

Regulatory Dialogue

There are perhaps three inter-related arguments why leaving global investment banking to the big five American banks might be problematic.

• The first is that this could leave Europe at greater risk from possibly ill-advised American political or regulatory intervention.

Oudéa (2015) wrote that:

“In the last crisis, American banks came under intense pressure to reduce their European assets. Having banks able to finance European companies is an essential part of the EU’s economic sovereignty. Europe’s industrial champions will be at a serious disadvantage if they cannot rely on access to capital when their rivals in America and China can.”

While this danger exists, it was already present before the withdrawal of European banks from global investment banking. Since the US dollar and US financial markets play the central role in the financial system, the US is in a position to enforce its demands on acceptable counterparty transactions and to dominate, for good or ill, the international monetary policy scene, whether or not the big five US banks are the only global ‘bulge-bracket’ banks left standing.

Moreover, the European Commission has started to put clauses in directives to give themselves the powers to recognise or not the equivalence of US, Swiss and other countries’ regulation and supervision (e.g. in the Financial Conglomerates Directive). The European Commission and the US authorities therefore set up an EU-US Regulatory Dialogue to discuss bilateral regulation issues. In some cases, the parties reached consensus (e.g. exemption of European banks from the leverage ratio for their operations and recognition of US prudential regulation and supervision as equivalent for financial conglomerates). In other cases, there is no consensus. A case in point is the accounting rules. While Europe adheres to the IFRS (International Financial Reporting Standards), the US sticks to its US GAAP (General Accepted Accounting Principles).

Competition

Five is not a large number.

• So, a second argument is that this will leave global investment banking much more concentrated.

Is this not potentially dangerous? Perhaps, but these five banks still compete quite ferociously, so margins are not rising all that much. The current economic pressures, especially of much greater capital requirements, impact the US banks just as much as on European banks through the Basel 3 framework. What would happen if one, some or all of these US banks decided to follow the European banks and to withdraw from providing global investment banking services in Europe, especially in London?

To a great extent, greater concentration, higher margins, and less liquid markets are the inevitable cost of imposing much higher prudential requirements. If much more capital is required to backstop risk-taking in such activities, then margins must rise until the capital employed in such activities earns the (risk-adjusted) equilibrium rate. This means that weaker competitors must depart, and concentration rises until equilibrium is restored. It is arguable that the sooner such equilibrium is once again reached, the better. Perhaps it would be good, rather than bad, if one or two of the US big five also packed up and left?

European Banking Becoming Parochial?

* The third argument is that current developments are inducing European banks more and more to concentrate on their national roles and clients in their investment banking operations rather than taking a wider European stance.

Deutsche Bank and Barclays are the only Europeans left in the top seven for the EMEA market. But they are likely to lose their positions because Deutsche Bank is currently undergoing a major reorganisation and Barclays is in the process of executing the Vickers split. In the investment banking field, the only pan-European banks will all soon be American. This has the corollary, for good or bad, that European national and EU-level authorities, such as the European Commission, will have rather less direct control over them. A key part of the European financial system is slipping out of the grasp of the European authorities.

It seems anomalous that, at a time when the European authorities are trying to establish a banking union and a capital markets union, the effect of their regulatory reforms has been to cause EU banks to concentrate their focus on their national roles, leaving the US banks as the only pan-European actors on this particular stage. But does it matter that the European authorities are left dependent on banks over which they have less ability to subject them to their demands?

There are concerns about US dominance in European investment banking. These are related to information advantages and soft relationships. The question arises whether US investment banks as outsiders are sufficiently knowledgeable about European corporates. Moreover, what is the loyalty of these US banks to European corporates in times of distress? Next, there are concerns about corporate culture. Not long after successfully taming the Global Crisis, US financial firms resumed their practice of paying high salaries and bonuses. In contrast, Europe enacted caps on bonus payments. The large US investment banks are already trying to exempt their high-flyers in London from these EU rules, by arguing that these managers have a ‘global’ role and should therefore be remunerated by international rather than European standards.

Policy response and conclusions

The European banking system is downsizing, partly because of on-going problems, partly because Europe is overbanked (Langfield and Pagano 2016). That should run its course. The consequence is that the big US investment banks will be the sole leaders in the global investment banking market, as the Europeans, including the Swiss, are in retreat. Thus the big five Americans are getting into pole position in the European investment banking market.

What should be the policy response? First, we look at the political side. With the decline of European banking (both in general and specifically investment banking), Europe’s hand in the EU-US regulatory dialogue is diminishing. Nevertheless, the European Commission is advised to strengthen its position in the EU-US bilateral negotiations and keep on viewing its banking industry as a strategic sector. The emerging role of the ECB, on both the monetary and supervisory sides, can be used in these negotiations. Of the 30 global systemically important banks (so-called G-SIBS), eight are located in the US and eight in the EU banking union area. A further four G-SIBs and the European head offices of the US investment banks are based in the UK under the supervisory watch of the Bank of England. The European Commission, the ECB, and the Bank of England should therefore jointly develop a strategic agenda with European priorities for their dealings with the US authorities. As in the US, this strategic agenda should be discussed with, and supported by, the industry. A strong and united front would enhance Europe’s position.

Second, we turn to the supervisory side. While Europe may lose some political clout, the supervisory implications are not a problem for it. With the move to capital markets union, the European supervisory architecture can handle the gatekeepers, which are becoming more US-dominated. The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) has powers under the Regulation on Credit Rating Agencies to licence and supervise the European operations of the primarily US-based credit rating agencies. Similarly, the relevant directives (Second Banking Directive and Markets in Financial Instruments Directive) give the relevant European supervisors (in this case the Prudential Regulatory Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority) powers over the London-based European operations of the US investment banks.

Third, the large corporates could themselves take precautions. For the bigger financing operations, a corporate typically hires a banking syndicate, which is a group of investment banks that jointly underwrite and distribute a new security offering, or jointly lend money to the corporate. European corporates would be well advised to include at least one (large) European investment bank in this syndicate, also in good times when they do not need them. That could help them in bad times, when US banks might be reluctant for whatever reason (including more detached decision-making). The involvement of a (local) European investment bank in the syndicate is not only useful for loyalty but also information reasons. Because of their local roots, the European banks have an information advantage over their US peers, which keep offices in New York and London. The practice of giving a European investment bank at least one place in further US-dominated banking syndicates could help to avoid complete dependence on the whims of the big US investment banks.

Finally, as the underlying financial architecture for banking union and capital markets union is still under construction, we do not expect big changes in the European financial landscape in the short term. If, however, further steps are taken to complete banking union as suggested in the Five Presidents Report (2015), including European deposit insurance with a fiscal backstop by the European Stability Mechanism, a truly European banking system might emerge with strong regional and potentially global players. But that is only speculation.

See original post for references

Those 5 US banks as well as its european and asian counterparts will only survive dependent on how “successful” is the attempt to bail-in depositors into the banks debts. We all know that banks derivative exposure is something like 10x the size of the world economy. There is absolutely no way that banks will survive the next 5-10 years in their present state. There are too many changes taking place in terms of technology (and yes I’m talking about crypto currencies but don’t bet on the banks blockchain projects since their patent applications reveal that all they are looking to do is to centralise a peer to peer technology!) as well as new enterprises such as peer to peer lending, wallet services, etc leave traditional banks with few if any activities that can provide added value to what they would consider their traditional clients or even new clients. What you’re actually looking at is the death of a dinosaur and the problem for deeply indebted governments around the globe is how can they continue to tax the population indirectly without their knowledge when technology is making these taxes more and more transparent.

I am constantly amazed that the EU is still being held together at all. Brexit is making all the news these days, but I haven’t read anything too encouraging about Spain, Italy, or Greece lately. Apart from the economic crisis, the US lead wars in the Middle East have put an immigrant crisis into a region of the world that seems ill equipped to handle it. I would expect the EU as an entity to unwind before any kind of banking union forms, especially given Yves observations that Germany is committed to deflationary pressures.

Sadly the immigrant crisis is a direct result of neocon policy going all the way back to Afghanistan, fortuitous timing wrt the currant economic dilemmas facing the EU [self inflicted due to embracing neoliberalism with poor underwriting wrt the periphery and part being the middle man between the east and west].

The EU is built like a Greek construction project: The top floor is deliberately left undone, complete with the rebar sticking out, because, once the house is completed, property taxes are due.

In the case of the EU, democratic oversight is well overdue.

The only inter-bank derivatives trades will be between US banks.

Good news for the rest of the world.

Bad news for US tax payers.

Yves, I beg to differ on securitization.

I’d say securitization creates outcome based on incentives, and in the US the incentives were much poorer than in the UK. No UK RMBS trust lost a penny to an investor in defaults, even those from Northern Rock and B&B. Even the dodgy buy-to-let trusts performed pretty well – but then, the incentives for (in effect) large commercial banks in the UK were much different from the US. And I don’t mean just financial incentives, but legal and political. Foreclosures were to be avoided in the UK (both for economic, but very much for political reasons as well – one reason for nationalising the banks here was that it would be a political suicide for any gov’t to instigate a wave of foreclosures as in the US), banks were in general their own servicers, and had incentives much better than the US foreclosure-mills etc. etc.

I’d say that in the US, securitization is unsafe, but it’s mostly because of the political capture of the system by the banks (which then translates into capture of the legal system, as nicely exemplified by the posts from the last week about “free” houses – it’s not ok for the borrower to get a free house, but it’s ok for the bank to get it). But from that perspective, while securitization is probably the most efficient way of getting the money out of the system, it’s just one of many. In fact, it’s own effectiveness my be its demise, as it makes the problem so much more visible.

Natural consequence of the ZIRP spigot being open on the US side. But where is the inflation that this giant tidal wave of money is supposed to cause?

(MMT: It’s because this money doesn’t intersect with the real economy, ever.)

the only way for big banks to grow now is to keep the rewards and discard the risks… so banking is no longer banking, it is just extraction. and overbanked is the word. it promotes a reckless competition that leaves taxpayers holding the bag – there simply isn’t room for all that risk without growing economies. the checks and balances of finance have been removed with “securitization” and bank competition causes gross instability because the more a bank succeeds the more profit they extract the more risk they fob off on everyone else in an economy that is not growing. and the only thing that is secured is a bank’s legal right to continue to extract, now on a global level. the best question is, how will banks survive when they can no longer extract all that securitized productivity? the EU is downsizing – must mean they see no other way; we are going global – must mean we are postponing downsizing until the world is so securitized it is flat broke.

Not sure I’m reading this right,,, among other things there’s this:

“US investment banks were the first to be hit in the Global Crisis and declined from 40% in 2009 to 35% in 2011, but recovered after the decisive recapitalisation exercise enforced by the US Treasury.”

In a nutshell saying the gov bailed out the big 5 by giving them money…I could use some recapitalisation imagine if I and four of my close friends went ben’s house one sunday afternoon and he said “I’m going to give each one of you 5 a billion dollars so you van trade amongst each other to recapitalize, then you can pay it back on simple secret terms because we want you all to feel good about yourselves and make some dough. Best if we keep this plan close for now though, because if everyone figures out whats going on you’ll have to share the profits and inhibit recapitalisation. It was a massive insider trading deal and the bernanks “recapitalize the banks” has been a thorn in my side from the first and those who claim the banks “paid it back” are…hmmm…can’t think of a nice way to describe them. These gangsters are now, thanks to agressive recapitalisation, on the brink of being the only 5 investment banks for the global cartel. Yes, I think this is a major problem and puttiing one’s self at the mercy of any of these institutions would be a dumb thing to do. We’ve really gone too far with this global control thing, especially as it’s banks who are in charge, why would anyone trust these people? They’re basically mafia. they chose themselves to be the winners in their self created crisis in the us, now they’re setting up to push it global using more disaster capitalism and people should be aware by now that the disasters will enrich the banks at everyone else’s expense. This really is the Hillary problem on both fronts, she wants global control for her banksters, but can’t say that out loud because then people will question why that would be good for them, as is happening now much to wall streets chagrin. Then there’s a fair amount of “don’t worry because regulators” which, considering the above, is comical. See Greece if you want to know who’s going to actually be “regulated”, it’s people not banks, see neg interest, bail ins offshore profit keeping, inversions, etc…the list is really long . Then there’s this:

“Third, the large corporates could themselves take precautions”…yes, by purchasing gov’t’s and blackmail they can continue to hold the world hostage. In the end I think the eurozone actually illustrates why this global cartel will fail in the same way that the EZ will fail, because it’s bureaucrats and technocrats imposing top down solutions where all the pain is felt by someone else. Add to that likely failure all of clive’s posts on the interconnectedness that we already have and failure will be an ugly ugly thing and I seriously doubt these big 5 expect to feel any pain, indeed they likely plan to extend their reach in the future crisis’ they intend to create.

this post requires a more thoughtful comment than i have time for, but here are some initial reactions?

-how would this change with a sanders presidency? the article presupposes a continuation of bank-friendly policies as would happen under a clinton presidency but that is hardly assured.

-is having a strong ibanking “industry” even desireable? are the banks beneficial to the real economy? statements such as

suggest that this is debateable. proprietary trading is highly speculative and unproductive so if banks are leaving because their ability to gamble is restricted, is that such a bad thing?

Excuse my coming to this discussion late…

My theory is that the asymmetrical regulation of banking by the US authorities is causing the decline of EU investment banks in favour of US banks. (David Buick of Panure Gordon on BBC a few years back is only one I’ve heard articulate this). The US authorities have many overt & covert ways of supporting the Feds shareholders (US banks) while forcing the EU banks off the field – while superficially appearing to be even-handed. (1) BNP- large fines and threats of not being allowed to use the dollar (2) exacerbating Deutsche’s structural problems (3) DOJ investigations into HSBC breaking US rules….Many cases of US extra territorial jurisdiction which the US wouldn’t tolerate if EU attempted it.

To quote from the piece: “Since the US dollar and US financial markets play the central role in the financial system, the US is in a position … to dominate….the international monetary policy scene”. But that domination is in the service of US banking and also the reserve status of the dollar. Having inflated the Feds balance sheet by 50 since 2008, getting a greater grip on monetary policy everywhere is important to ensure the dollar holds its value.

Others have noted that the EU would have reached debt forgiveness terms with Greece and Ireland early in crisis had it not been pressured by Geithner et al not to trigger default events that would have lost AIG and others fortunes thru derivative exposures. The Fed gave more emergency funding to EU banks than it did to US banks at the height of the crisis. So from the get-go the EU response to the US originated-crisis has been framed by US for US ends. The Eurozone crisis could have been managed quite differently without these impositions. We can’t exclude the political either: the Greek crisis last summer was settled in the light of NATO’s (i.e. US) interests in “solidarity” over those of the EU economy.

Germany sacrificed alot of kudos as the “good European” in appearing to be harder on Greece than the IMF. The IMF is still pressuring the EU to unilaterally forgive Greek debt. Michael Hudson has pointed to the IMF rule change in December 2015 as evidence of how much the IMF is a tool of US (financial and political) policy. Unilateral Greek-debt write-down by EU banks without US banks (IMF) also taking a hit will disadvantage EU banks – mainly German & French. I suggest this will weaken the German banking system overall – which is over 50% state owned – and allow further inroads into German industry for US banks and the Anglo-US model of speculative banking, exploiting the German “Mittelstand” to underwrite Wall Street’s speculative behaviour a little longer, sustain the dollar a little longer, but undermine the German industrial banking model, and hence German industry – long term. This is why, I suggest, Germany is pursuing the policies it is. Whatever the future holds, be it a breakdown or reconfiguration of the EU, the demise of the dollar, war, etc, Germany’s only salvation- economically and socially – is its domestic industrial economy. Saving that comes ahead of saving the EU. Germany cannot really underwrite the EU or EZ project at its own expense while the US (and hence US financial interests) have the upper hand in ultimately dictating European events thru NATO.

I have to tell you that pretty much everything here is off base, save for the considerable advantages that the US banks have via the dollar being the reserve currency.

1. US banks do not own the Fed. They have non-voting preferred shares. US banks can’t get anyone at the Fed fired, unlike unhappy private shareholders (stock price declines and scandals do lead private boards to fire CEOs). Congress just cut massively cut the dividend that the member banks get. Since when does Congress get to cut the dividend of a privately owned institution?

2. AIG did not have derivatives outstanding that would have been implicated in an Irish or Greece restructuring. It has been well publicized that the reason for forcing the Irish government to assume the debts of Irish banks when it was not legally obligated to do so was to protect the German bank, Hypo, which has bought Irish bank Depfa at a top of market price. Similarly, the big beneficiaries of the Greece bailout were French, Greek, and German banks, in that order.

Better conspiracy theories, please.

Yves

Thanks for reply. At last a chance to have my “conspiracy theory” critiqued!

First your points:

(1) Its not in terms of dividend or capital appreciation etc that Fed acts in interest of US big banks, its in – lets call it what it is – rigging the system in their ultimate interest. What else is QE and zirp/nirp?? Smaller US domestic domestic banks are also disappearing under an increased regulatory load: how is it that under the same regulatory load only the majors continue to build market share and absolute size?

(2) Notwithstanding the proximate details you mention of the Greek or Irish collapses, its the systemic inter-relatedness through globalised financial markets that ultimately caused the the EU & ECB authorities to declare, in agreement with the Fed: “no debt write-downs, no burning of bond-holders” i.e. its too dangerous to interfere with. Nobody knew (or knows) where a greater blow-up may occur due to a credit event somewhere else. And ultimately a significant event will express itself in the US derivative market, which predominates (currently at 90%, I gather). A market now perhaps 10 times the size of the global economy, a market of fictitious capital that is held together by a mixture of law and convention – predominantly US law and US convention, exported to other financial centres. Its in the interest primarily of the major US banks that it is held together, and the interest of all of us that it is dismantled in a controlled way – but that’s not going to happen as it is the basis of US financial power, which the EU has to go along with.

Please let me know specifically what else is “off base”.

As regards conspiracy theories, I like the line from one Benjeman Cohen, “No conspiracy is needed to explain a pattern of co-operation when there is so evident a confluence of interests”, quoted in Panitch & Gindin’s “The The Making of Global Capitalism – The Political Economy of American Empire” (Verso 2013). Panitch & Gindin suggest that it is the unique ability of US domestic institutions – the Fed, The Treasury, major Wall Street houses – to intervene globally to solve, defer or displace crises of globalisation, essentially to resolve them in particular US actor’s favour. This gives contemporary global capitalism its American character. It institutionalises in global capitalism particularly American norms and mods operandi – and makes certain US actors its primary beneficiaries. (Elites elsewhere- like EU MNC’s and major banks – are co-opted in this program).

The French social philosopher Pierre Bourdieu observed as far back as 1995: “… the rationalism …which inspire(s) the models of the IMF and World Bank, that of the law firms, of the great juridical multinationals which impose the traditions of American law on the whole planet… leads people to act as if they had the monopoly of reason….Economic reason (is) often dressed up in juridical reason…(It is) a nationalism which invokes the universal in order to impose itself….”

I understand you respect Michael Hudson, so i will have to rely on him as witness that the IMF is a tool of Wall St, that US political policy is in the service of Wall St (Panitch & Gindin would widen that to US MNC’s – but all MNC’s are now basically financialised ). Its also Hudson’s suggestion that EU was set on its current track over Greece, Ireland and EZ by direct political intervention from US Treasury. Panitch & Gindin show that the Fed pumped more into EU banks than into US banks in the heat of the crisis, and indeed the article supports the view that after Fed and Treasury actions saved the US-EU joint financial system the “decisive recapitalisation exercise enforced by the US Treasury” led to a rebound to new heights (from 35% to 45%) in US bank activity in the in EU. Absent initially saving the system and the “decisive recapitalisation”, whither the dollar and global capitalism now? A big and dangerous economic and political mess, I fear.

I rely on Wolfgang Streek of Max Planck Institute who suggests that NATO considerations prevailed over EZ and Greece economic considerations in last July’s denouement with Greece & Troika. It most plausibly explains Syriza’s volte-face.

Many reports support the idea that the US is redoubling its efforts in extra-territorial jurisdiction of the the dollar and non US institutions who use the dollar.

Hudson and others (Ellen Brown, Nomi Prins, plus online commentators) point out that US regional banks are the shareholders of the regional Feds, who are in turn the members of the Fed board, and that the Fed acts primarily in the major banks interests. (Panitch & Gindin hold that the Treasury is the more pivotal institution in global capitalism). Of course holding the dollar system together is a pre-requisite of maintaining the dominance of the US over it. It is no accident or natural economic outcome that, quoting the original article again, “the US is in a position … to dominate….the international monetary policy scene”. It is the outcome of WW2, Bretton Woods, of the Cold War etc, policies of US dominated institutions, the IMF, World Bank, BIS. It is ultimately political-economic and, as we increasingly see, military in nature.

I’m not suggesting there is an overt and unified consciousness somewhere in Germany on the course I am suggesting it is on, but the sum total of its institutional actions amount to this, if only in defending proven German norms from outside imposed change which it considers antagonistic. As Tariq Ali has pointed out, even Germany sovereignty is circumscribed by history and NATO membership.

Finally, this note on the nature of conspiracy. Yves Blot (French scholar and politician) speaking on RT (18 March 2016) : “….BNP Paribas… had to pay enormous sums to the American Treasury ($9bn) because they made business with Iran. I know ….the American government told the French government, in private, naturally, that if we (sell) the Mistral (warships) to Russia, the sum that BNP Paribas must pay will be much higher . At the same time, they say that American judges are completely independent. I don’t think this is the case. There are contacts between the judges and the American government. I have some experience with this. Western countries always say that their judges are completely independent, but it’s not the case if it is a question which touches national interests. For little private conflicts the judges are independent, but if it’s linked with politics, the government says “I hope you will give good sanctions against this bank”, for instance….”.

(I would have no hesitation is supporting Mr Blot’s assertion from an Irish perspective: there is little doubt that regulators and government here all wore “the green jersey” in supporting Irish finance and economic entities during the “Celtic Tiger” years, in giving “national champions” the edge, either by ommission or commission, where, if they doing their job properly, they would not have).

Reminds one of the nature of conspiracies and England’s King Henry II distancing comment in 1170AD: “Who will rid me of the troublesome priest?”. Benjamin Cohen’s quote seems most apt to me. Panitch & Gindin suggest its wrong to see all this in purely nationalistic terms, elites everywhere benefit. But they are induced to benefit by the actions of the pivotal actor(s): the US domestic state institutions who act ultimately to hold a system together that benefits some US actors most.

You posit the decisions of the ECB and EU as being driven by the Fed. There is NO evidence for that. The Germans who were huge drivers of this didn’t want Hypo Bank to fail due to contagion risk. That meant no Irish writedowns. The French, who are the other big heavyweights in the EU/Eurozone, didn’t want their banking system to go tits up due to Greece. And that’s before you get to the fact that in those days, periphery country bonds were all trading similarly, so you had “contagion risk”. You seem to forget that a banking system collapse in any country (like Greece) would also imply a sovereign default, which would intensify the sovereign funding crisis in Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and even Italy. You completely forget how entwined the sovereigns and the banks were.

Moreover, almost all of the perceived to be top economic programs are in the US, and the one or two also rans are in the UK. So they all think like American economists.

You keep claiming direct influence by the Fed and ignore that cognitive capture is even more powerful and has the greater advantage of not requiring arm-twisting. My God, Draghi heads the ECB. Need we say more?

Lawrence Summers (B.S., 1975)

Mario Draghi (Ph.D., 1976)

Paul Krugman (Ph.D., 1977)

youtube.com/watch?v=Cj-vIbtAl5g