Hope (and Change) in the Labor Market?

By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

I want to quickly dig into Neil Irwin’s article in The Times on April 1 — headline: “This Is the Job Market We’ve Been Hoping for All These Years” — essentially because it is better to post than to keep pounding my head on the desk. Start with the headline: Who, exactly, does Irwin mean when he writes “we”? (A question you should always ask.) We can guess (and I’ll do some guessing later) but it’s a virtual certainty that Irwin’s “we” does not include, well, the sort of person who actually has to go out on the job market and get a job the old-fashioned way (that is, not by using LinkedIn, or one’s carefully nurtured personal network, or one’s seat-mate on the Acela, or other “meritocratic” techniques).

Let’s start where Irwin starts:

If you were going to sit down and sketch out an ideal scenario for the American job market in 2016, it would look something like this:

The United States would keep adding jobs at a steady clip. Wages would rise gradually — enough to put more money in workers’ pockets, but not so fast as to lead the Federal Reserve to move abruptly to keep the economy from overheating. Steady job growth wouldn’t show up in continued drops in the unemployment rate, but rather in a rising labor force. That is, people who had stopped even looking for a job in recent years would come back into the job market, allowing for strong job growth mixed with a steady jobless rate.

That happens to be the reality revealed in the March jobs numbers released Friday, and really in every jobs report published so far in 2016.

To be fair, Irwin immediately qualifies his ideal: He notes that productivity growth is “exceptionally weak, and that “incomes for working-class[1] Americans haven’t really grown over the last couple of decades.” But ideal it is: The headline is not a question, but a declarative sentence. Irwin concludes:

The economy has a lot of profound problems, and the damage of the 2008 recession is still not fully healed.[2] But the March numbers offer more comfort that, in terms of the job market at least, it’s heading in the right direction.

Remember, however, that for Irwin, the “right direction” includes flat wages and weak productivity. Remarkably, however, Irwin doesn’t consider the nature of the jobs created at all! But what if all the jobs are crapified? How is that “hope”? Even more remarkably, Irwin’s column of the previous day (“With ‘Gigs’ Instead of Jobs, Workers Bear New Burdens”) strongly suggests that crapified is just what those jobs are:

There’s a bigger shift underway. That’s a key implication of new research [Lawrence G. Katz and Alan B. Krueger (PDF)] that indicates the proportion of American workers who don’t have traditional jobs — who instead work as independent contractors, through temporary services or on-call — has soared in the last decade. They account for vastly more American workers than the likes of Uber alone.

And new jobs created since 2005 net out to these “non-traditional” jobs:

Most remarkably, the number of Americans using these alternate work arrangements rose 9.4 million from 2005 to 2015. That was greater than the rise in overall employment, meaning there was a small net decline in the number of workers with conventional jobs.

And here’s what “we’ve been hoping for” and “right direction” mean if you’re actually in the working class:

But over all, there’s little doubt that workers in these nonconventional work arrangements carry some of the burden of protecting themselves from misfortune that employers traditionally have carried.

(For example, by being forced onto the ObamaCare exchanges, instead of having employer-based health insurance.) The question of whether “We’ve Been Hoping For” flat wages combined with crappier jobs and more risk doesn’t seem to occur to Irwin.

Let’s turn now to the “Changes” that have caused to the labor market “We’ve Been Hoping For” to become what it is. Katz and Krueger suggest four (which I’ve bolded and numbered):

Many possible factors could have contributed to the large increase in the incidence of alternative work arrangements for American workers from 2005 to 2015 that we have documented in this paper. Although a fuller evaluation will have to await further research, here we provide an initial evaluation of some leading explanations.

[1. Education] The first explanation is that alternative work is more common among older workers and more highly educated workers, and the workforce has become older and more educated over time. A shift-share analysis, however, indicates that shifts in the age and education distribution of the workforce account for only about 10 percent of the increase in the percentage of workers employed in alternative work arrangements from 2005 to 2015….

[2. Technology] Second, technological changes that lead to enhanced monitoring, standardize job tasks and make information on worker reputation more widely available may be leading to greater disintermediation of job tasks. Coase’s (1937) classic explanation for the boundary of firms Specifically, we divided the sample into 30 age-by-education cells. If we assign the fraction of workers in each cell that was employed in an alternative work arrangement in 2005 based on the BLS CWS and allow the share of workers in each cell to change according to the observed changes between the 2005 CPS and 2015 CPS, we predict that the overall share in workers employed in alternative work arrangements would have risen by 0.5 percentage point, compared with the 5.7 percentage point increase that was actually observed. We reach a similar conclusion using the 2015 age-by-education distribution from the RPCWS. 18 rested on the minimization of transaction costs within firm-employee relationships. Technological changes may be reducing the transaction costs associated with contracting out job tasks, however, and thus supporting the disintermediation of work.

[3. Reduce rent-sharing] Third, Abraham and Taylor (1996) argue that contracting out is often sought because firms seek to restrict the pool of workers with whom rents are shared, as well as to reduce the volatility of core employment. A rise in inter-firm variability in profitability is thus consistent with a greater desire for contracting out to reduce rent sharing (although increased contracting out could also have contributed to the rise in inter-firm variability in profits). Relatedly, Weil (2014) argues that competitive pressures are causing a “fissuring” of the workplace, with either workers being misclassified as contract employees or work being redefined to make greater use of contract workers and independent contractors.

[4. Reserve Army of Labor] Finally, it is plausible that the dislocation caused by the Great Recession in 2007-2009 may have caused many workers to seek alternative work arrangements when traditional employment was not available.

Of the four proposed reasons, Katz and Krueger reject the first. Of the remaining three, it seems to me that there’s a single, abstract factor each shares, and that is not mentioned by the authors: That would be the power imbalance between working class (that is, “we” who sell our labor on the job market for wages) and the — dread word — capitalists who purchase that labor. After all, “technology” has no existence outside the social relations within which it’s embedded; why, after all, shouldn’t “enhanced monitoring, standardized job tasks, and information on worker reputation” lead workers to organize production on the Twitter? Of course, Katz and Kreuger recognize the power imbalance explicitly in points three and four, although they don’t treat the imbalance as problematic in any way.

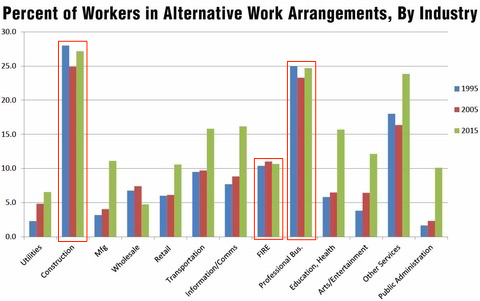

Is there any data that would suggest that “the job market we’ve been hoping for” is the result of such an imbalance? I think there is. Katz and Krueger explain that their study is a version of the BLS Contingent Worker Survey (CWS), not performed by the BLS since 2005 for lack of funding. Patrick Martin integrated BLS CWS data since 1995 with the Katz and Krueger data, and came up with the following chart:

As you can see, there are three industries that in which workers have stabilized their “alternative work arrangements” more successfully than others:

- Construction

- FIRE

- Professional and Business

Speculating freely, let’s look for power imbalances distinct to each sector: The power imbalance that protects workers in Construction would be unions; in the FIRE sector, the political power of the FIRE sector itself — it is, after all, running the country — combined possibly with the sector’s conception of itself as a relationship business, along with a hush money dynamic; and the Professional and Business Sector, whose political power is such that they won’t be subjected to global competition under TPP, unlike, say, steel workers, which is why many of us must travel to get our teeth fixed. (Particularly tragic is “Public Administration.” Remember when we promised civil servants steady employment and a respectable pension? Good times.)

What is to be done to bring hope to “us,” if “we” are subject to Irwin’s “alternative work arrangements”? Sadly, the muscle of the FIRE sector, or the construction unions, or the professional guilds, is not available to retail workers, or truckers, or nursing home attendants. There, efforts on the scale of #FightFor15, with goals as high as single payer (since employers want to dump insurance, and ObamaCare is what it is) look like the “change” that would be needed.

It’s an April Fools post. Which pretty much characterizes the corporate media 24/7/365.

Said no one who is an average worker.

All segments of the labor market are not equally crapified because we didn’t promise equality of outcomes; we only promised equal opportunity! /sarc

And in today’s NYT, a similarly clueless piece:

Will You Sprint, Stroll or Stumble Into a Career?

Unsaid, but also highly recommended: a trust fund.

The narrative is that it’s about the individual young people and their strengths or weaknesses,

not about the system.

Curious that the wholesale sector seems to be bucking the alternative trend since 2005.

Lambert,

BLS says only 13% of construction workers are union. This scans with my experience, and while union costs add maybe 5% to overall construction costs in NYC, they are not in my opinion the main factor that has preserved the remunerative quality of construction and construction related work. The main factor is that construction is necessarily site specific and as a result resistant to automation.

In addition, constructions’ strong boom bust cycle weeds out experience as it begins to bloom, displacing all but the most skillful and best paid. By the early 90’s crapification had run its course in construction as the lump of labor replacements for skilled tradesmen, union or non, created more down stream costs in law suits and other post occupancy expenses than simply paying skilled people to not fuck everything up.

Safety and performance requirements in OSHA and building codes have also selected for intelligence in the work force increasing the quality of workers in areas with strict enforcement regimes like the coastal cities East and West. In non coastal America I suspect construction pay quality is strictly due to the site specific nature of the work: even on a modular house, skilled labor is required in the factory and someone with a brain has to deal with all the particulars of a specific site.

Awesome comment, thanks. Would you guess that the other sectors with similarly stable ratios of “alternative”/traditional ratios have similar structures? (I wonder if “site-specific” has an analogy to local and state law in the legal profession, for example.)

There will come a time when whole houses, even “custom” will be designed, cut, packaged in China and shipped to any job site in the USA. (We’ll even supply the lumber)

Hate to see it happen, but there it is.

You fail at graph reading. Construction and Professionals didn’t avoid crapification, they were already crapified prior to 1995. Over 25% “alternative work arrangements” for those sectors in 1995, the other sectors are just starting to approach those numbers.

I failed at writing. What struck me in the graph was that those three sectors were strikingly stable over two decades. I revised the wording accordingly.

I can’t think of another explanation than different balances of power in the various “industries.” If you have one, I’d like to hear it. (Each of the stable industries could be a “two-tier” arrangement, perhaps.)

Anecdotal, but nearly everyone I worked with in construction was an independent contractor for tax purposes, whether they actually fit the description of one or not. For the big employers, this is a good way to cut labor costs and reduce administrative overhead; for small employers it is a necessity to stay competitive price-wise with the big guys. Having employees is expensive.

I’d have to agree that while construction freelancers have remained steady as a percentage, it’s a crappy equilibrium they have reached — and likely reached for reasons external to worker power. It may be that construction is the “leading indicator” here, having already reached its maximum possible level of labor squeezing, and other sectors can now be expected to catch up.

You could be right in that the bottom is in, but I dunno. Lots of hacks came out of the weeds post 2008, the former “housing developers” went upscale.

And they underbid everyone with incompetence. It’s a huge theme around here on the smaller end of things, getting toward the middle.

The whole industry is built on cut outs and middle men that serve no purpose but to allow these “independent” relationships.

I could write paragraphs, but I’ve been trying to get out of the industry. Too much headache, and no real “buyer” to work for. It allows for everything but responsibility to trickle up.

“The whole industry is built on cut outs and middle men that serve no purpose but to allow these “independent” relationships.”

Those cut outs and middle men would go into the “business and professional” bucket, I guess.

Who do you mean when you write “we can guess”?

“We” readers, in that instance :-)

I make it a policy to assume that I can also speak for everyone who we’s me.

I don’t see how productivity can increase, until the “Xavier Scool for Speciaal Humans That kaN’t fInD WorK to gOOd” locates Super Waitress***

Super Waitress will be able to split into multiple bodies and handle more tables but only demand one paycheck. That makes the productivity calc work. A great pair of boobs, and voilà, tips make it a “living wage”.

I believe Fukushima will bring this about sooner or later, but we should consider having some more nuke “accidents”‘ just to hedge our bets.

*** The X-Men are an equal opportunity place.

you said that so much better than what I was thinking. that’s why I always wait.

They call it the Jackpot for a reason, besides irony: There are winners.

The FIRE sector is the only one for which your analysis is correct – based on the graph. Even in 1995, both ‘Construction’ and ‘Professional business’ already suffered from massive, baseline levels of contract/contingent employment — around 25% each.

Outside of the Northeast, construction work has been pretty unburdened by unions throughout this study period, and the guys who’ve been employed in it have taken what they could get as they best could. Just like many “professionals” outside of the protected guild structures of law and medicine.

‘Professional business’ is a nebulous category which likely encompasses the sciences and engineering, and possible some “tech” or IT employment. All of these ‘professional’ sub-sectors have been slaughtered by contracting-enabled wage arbitrage throughout the study period in this graph.

The professional class rage that is so talked about now is on account of how this beat down has progressed………… to impinge on the lives of those who’d planned to be lawyers, doctors, etc.

As above, it’s the stability in the three that I find striking. If there’s another explanation than power imbalance, I’d love to hear it; obviously, I’m not an expert on those markets, so I’d love detail about them.

Is there really “professional class rage”? Organized in any way? One doesn’t hear much about it in the press, although, for doctors, I suppose PNHP might be an expression.

Yes, these 3 are stable compared to the other sectors broken out on this graph. I’d argue that the upswing in contingent employment indicated in most of the other sectors since ~2000(?) documents a downward spiral that had already hit the parts of our economy where men made real stuff.

What I tend to believe (without any real data) is that the power imbalance that surged in the other sectors during the past 20 years came to be earlier in the ‘professional business’ and ‘construction’ sectors. Look, 25% contract or contingent employment in 1995? Even I didn’t realize how bad it was, and I lived it. These 2 sectors were already hellishly insecure in 1995.

I’m still assuming ‘professional business’ is heavily STEM employment, and this assumption may be wrong. But if so, the graph supports the idea that jobs, or ‘careers’ where people make actual things, concrete stuff, have been getting the short end going back +30 years.

“Business and professionals” seems like a mish-mash:

1) STEM

2) credentialled, like doctors, lawyers, accountants, therapists

3) management, small business owners

But yes, the makers of concrete things got gutted.

The closest thing I’ve seen to what could be called “professional class rage” is when slashdot runs an article about H1-B visa abuse. Its worth keeping an eye on slashdot just for those articles. (I’ve been a member there since the 1990’s…. sigh I feel old)

There is plenty of professional class rage amongst Attorneys. Lots of personal blogs have popped up over the last five years of what a scam law school is. My husband is still living the nightmare of that sector of the economy and knows plenty of others as well. As for STEM in civil engineering if a company doesn’t have a project or two going it leaks extraneous engineers who then have to pick up and move to where the jobs are. If you have a family this can get pretty exhausting after awhile. I am four years out of the civil engineering job market and am trying to decide if I can squeeze back in in a couple of years or if I should just make a career transition. Nothing sounds very promising right now. Three kids in daycare if I go back to work right now.

Yep, I know promising young law students who are going into HR or something else after they get the degree.

I’ve been in manufacturing for the last 30 yrs and we were the leading indicator. Spent 30 yrs on the bottom getting the rug pulled out from under me over and over. I’m leaving now at 50 and starting over. No amount of school made any difference.

As for engineering, I’ve a few in my family @ the PhD level — the best engineerng to be in, is defense contractors. Trust me on this, the pay is amazing and its pretty steady, maybe a 20-yr turnover.

Same industry. Shit work.

Make great money….but constant moving and boomtown effects eat all of the “great”. It’s also way too convenient it is to find work “out of town”, but none inside, even though there is work. They brought people in from out of town for that.

I gave up, fell back.

I’m civil also. I keep saying that they can’t keep letting things get this bad, eventually they have to start fixing things…and nothing changes. Munis are backing shopping malls instead of infrastructure. Anything federal was spent before it left DC.

knife catching….is it the bottom?

Ah, yes. Now that I think of it, I remember one such blog.

Can you recommend any sources?

Because the rage doesn’t seem to be organized. I don’t see it showing up in the political campaigns (unless they’re voting for Hillary, which seems dubious).

I think there’s some level of prof rage among attorneys, where the jobs have all gone away – some work sent off-shore to English speaking third world citizens (usually India) for some of the work – and there’s less jobs and less money to pay attorneys decent salaries after plonking down ginormous sums to get an undergrad degree + a JD and nowadays maybe even have some other degree, like an MBA, or an engineering degree or even an MD. It’s crazy what degrees and levels of experience attorneys are expected to have. Only so many jobs out there are really high paying, contrary to what you see on tv and in the movies.

IT is another sector that’s been constantly downgraded due to H1(b) visas. One can find a job nowadays, but usually at a lower salary than it should be.

The issue with “professional rage” is that no one really does much of anything about it. The notion of actually organizing is déclassé or something. Plus a lot of that anger has been cleverly mis-directed by the great propaganda Wurlitzer to blame all the issues on the usual suspects: poor people and undocumented workers.

Yeah, really! How the eff do poor people or undocumented workers cause financial problems for, say, younger newer attorneys or IT types, you may ask? Well the shorter answer is: they don’t. But let’s all get our knickers inna giant bunch bc some poor person is getting all of this “free stuff” doncha know?? And I’m stuck paying ginormous college bills, and all I can get is this crappy low paying job.

You would think people might connect the dots, but they don’t. I read something yesterday where apparently Ivana Trump climbed out of her crypt or something to shake her angry fist at undocumented workers who, apparently, are ruining Ivana’s precious life, and we should all vote for her “ex” because he’ll “fix it.” I guess Donald gave her a big bonus or something.

These people! They just love to demonize the poor and undocumented workers, and then they think that solves everything.

So yeah, I think there’s professional rage out there, but the problem is that most of those numbskulls read Ayn Rand and think being Libertarian is the solution. Go figure.

Is that what they do? Somehow I don’t see being a lawyer as a close analog to being Howard Roark, but perhaps the KoolAid is strong.

Doesn’t “professionals” consist heavily of lawyers and accountants? Dean Baker has said both are effectively unionized, through professional certification requirements.

And I have to disagree with the multiple assertions of “everything was terrible as of 1995” in that field. I know a lot of small firm professionals (lawyers, IT, accountants). They all agree things were MUCH better in the 1990s. Clients paid faster, were more appreciative, work easier to get then than now.

What jsn said.

Additionally, “alternative work arrangements” are pretty much SOP for construction, with its ebbs and flows. Some guys work for years uninterrupted, others get laid off during downturns and either start their own small firms, do something else for a while, or just live in much reduced circumstances. Come to think of it, most middle-aged construction workers I have known in my 20 years in this business live pretty much under their pay grade most of the time. Some of this is inherent frugality due to swings in job participation, and another factor could be the lack of status envy among this particular group of people – fancy jewelry, European vacations, expensive clothes, and imported vehicles just aren’t important status markers.

start their own small firms

At least they have an easier time doing that than people in IT (thanks to the infamous section 1706 of the IRS code).

I live in NYC, which is mostly not representative of anything but itself, but in my construction experience a long time ago, combined with the continuing experience of a close friend who is a third-generation local builder, it should be pointed out that even thirty years ago, outside of the rapidly-shrinking union realm, much of the employment was not just temporary, but totally contingent 1099 work. Most people I knew weren’t employees at all, even if they worked most of the year for the same contractor, at least in the earlier stages of the careers. It’s the nature of the work, for endogenous and exogenous reasons, and it anticipated the increases we see in other industries.

As others have pointed out, the increase in “alternative” employment – presumably a more easily digested way of saying “contingent,” let alone “vulnerable” – in public administration is a major change, with profound long-term consequences. As a public school teacher, I see it everywhere, even in a “union town.”

You say “rent-collecting, parasitical middleman” like that’s a bad thing!

Judgements from my own experience always seem like wild speculation, but I have a reasonable amount of familiarity with construction law as well and can say yes, it is very locally embedded. Things like MERS and TPP are attempts to get around this but haven’t worked, yet.

Most of my experience has been running a small business and that is definitely a locally embedded occupation where trust is at a premium and thus personal relationships hedge against crappification and outsourcing. On the other hand, post 2008 most of the markets I served simply vanished and I was very lucky to be able transition to other markets.

But highly asymmetrical crappification is showing up in law: I saw some recent service papers in NYS saying you have 20 days to respond if you are served and 30 if you aren’t, begging the question, “how do you know if you aren’t served?”

I expect this is how Iran ended up with a billion dollar summary judgement for the 9/11 WTC attack!

This was supposed to go to Lambert above!

PQS, I was going to comment to you that what I’m seeing is a very real greying of the construction labor force as those who figured out how to live with the ebbs and flows of the industry, like yourself, are aging while the chaos and insecurity, probably coupled with student debt, keep capable young people out.

Is that particular to my experience or are you seeing that too?

Yes. There is a definite greying of the workforce. However, I’m in the white-hot Pacific Northwest, so I do see more younger guys getting into the business these days due to sheer volume of work. I don’t know if the swings in the aircraft business contribute to people making choices to go into construction, but I’m pretty sure Boeing isn’t the “lifetime employment” deal it once was, if ever.

If we weren’t such a racist, sexist, and otherwise stratified society, I think a serious investment in trade schools would be a huge benefit to society, individual careers, and everything else long term. Unfortunately, I know “who” would be pointed in that direction by the People Who Rule Us, and it would quickly turn into a bad deal all around, I’m afraid….

Construction is also one of the few fields that seems to retain the apprentice/journeyman/master model not unlike the medieval guild societies. It is also very firmly grounded in familial connections. Grandpa/Dad/Son/Grandson is not an uncommon company model in the industry. And successful, too, with a resilience you don’t find in the feral employment world.

“Judgements from my own experience always seem like wild speculation”

No, I don’t think so, in the sense that any personal narrative can resonate far beyond one person.

And as soon as we stop looking at labor markets from the outside through statistics, and from the inside, from lived experience, judgments from “my” (“our’) “own experience” is all we have to go on.

And Irwin, perhaps as a result of a deformation professionelle, does not seem able to do that, which is why he’s able to write a column on the precariat one day, and then 24 hours later a paen to the ideal labor market that necessarily includes that precariat.

The reason you have to travel to get your teeth fixed is not due to some mythical political power of dentists. The dental business is rapidly becoming wholly owned by private equity investors. Dentists are well aquainted with the gig economy, especially specialists. It is not unusual for a new orthodontist to take several part time jobs with various corporation dental clinics. The professional class of dental healthcare professionals is as much as victim of crapified jobs as the rest of the U.S.

Hmm. One wonders whether the role of private equity could be generalized across all the unbalanced sectors. (I’m thinking of how they thought it would be a good idea to become property managers, or to hire it done. Unfortunately, “you gotta know the territory,” as the Music Man sang, and all buildings are “locally embedded” (brilliant phrase).

Neil Irwin’s not too bright to begin with. He wrote this on Trump claiming there’s a 42% unemployment rate:

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/11/upshot/the-real-jobless-rate-is-42-percent-donald-trump-has-a-point-sort-of.html?ref=business&_r=1

According to Politifact, Trump was quoting Stockman btw, but Irwin was too lazy to check.

And according to the BLS and the Chicago Urban League, the 42% figure is valid for some youth.

Irwin’s counterpart on 538 is Ben Casselman, who wrote this:

http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/what-is-the-real-unemployment-rate/

Casselman’s not much better either.

It pains me to say, but the WSJ has a pretty good article on why the economy hasn’t shown any signs of life:

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2016/02/26/in-36-states-unemployment-rates-still-linger-above-prerecession-levels/

and this too:

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2016/03/17/half-of-u-s-may-endure-lost-decade-of-depressed-employment/

Is it too much to wish for that Irwin and Casselman both get to experience unemployment first hand?

Well I dunno about that. It depends on the definition of what’s in the Prof & Bus sector, but it’s been obvious for a while that there’s outsourcing of white collar jobs to third world countries, especially India, where many speak and write in English very well. Law is one area where this is happening, and I only expect it to continue. I’m not sure what the effect of TPP will be on this sector, but I’m not feeling like it’s going to be a positive outcome for US workers.

Thanks for breaking down that article, which I had heard about. It is an April Fool’s joke, as far as I’m concerned.

On a somewhat tangential note, Sacramento, like many cities, is experiencing an explosion in homelessness. It’s clear that many of the “newcomers” are not the usual situation of mental illness and/or addiction problems. People simply cannot get jobs that pay enough for people to pay for adequate housing. One major disaster – a car accident, a big medical bill – and these people find themselves on the street. This includes seniors in their 80s, who really cannot work anymore.

Sacramento appears to be maybe finally getting off of its collective @ss and figuring out what to do… which way mean tent encampments. Has anyone ever been to India? Not to diss a wonderful nation that I love, but I’m here to say that we’re looking more and more like some of their slums (no offense) in major cities there. Yet this stooge writes this lying nonsense.

Articles like this one really piss me off.

As a 30-year resident of Sacramento I have seen the explosion of homelessness there as well. I had been very involved at City Hall with the occupiers and at the state level with the right to rest bill SB 876, before I gave up and left the country two months ago. It would be wonderful if some of those city leaders would quit criminalizing the poor. But the hate reaped on the homeless by the residents and businesses of downtown and Midtown Sacramento is way over-the-top.

Where did you move to??? What’s the best place to go?

It’s my question. Serious. I think about it.

The city hall protests have mostly fizzled away here in Sactown. I brought them lots of food over the time they were there. Sometimes they are still at the capital. I hope that something is done. The Sac Bee, fwiw, has written some very good, worthy articles about the homeless lately highlighting just how many are people who have fallen on hard times.

Those articles also highlight how totally ludicrous the “system” is to get help. It’s insane and really tragic. Just awful.

Where did you move to?

Also, thousands of inmates have been released from prisons in California since the passage of Prop 47 and 2014. Unfortunately, there are very little in the way of programs to help these releasees find work and housing. Consequently they end up contributing to the homeless problem. It’s like the powers-that-be want the release to fail, and want the public to reinstitute mass incarceration.

This is also accurate, and we see it in the public libraries every day, as well as elsewhere.

It’s that line on the app about convictions, which in most cases is a violation of the constitution, if it was something other than a unicorn itself.

The article read like Clinton talking points and betrayed a real lack of understanding of the contents of Non-Farm Payrolls report. Is this guy a stooge for the Clinton campaign?

Note also the Times shut down the comments after 25 comments; very unusual and typically happens when comment writers are burying the facts/opinion of the writer with real facts and considered opinions by those that actually understand the economy and the labor market – which sucks by the way. Not everyone wants to be a nurse’s aid, waitress or work at Target but that’s about what’s on offer.

Shouldn’t “we” be ecstatic that consumerism has finally driven over the cliff and crashed onto the rocks below? The good outweighs the bad, huge sigh of relief for “us”.

Sequencing. The better time for consumerism to have crashed and burned would have been before workers’ capital had melted into air. Had more people had the wherewithal to relocalize while shutting down mass consumerism, the vast majority of us at the bottom would have realized gains in living standards (as measured from a non-consumption-centric standpoint) to cushion the blow.

Whats this thing call a labour market when what we have is a labour pool….

Skippy…. more reminiscent of fracking extraction of a pool of energy…

Yup. Blow the hell out of it and suck up what you can after.

Wait a minnute, that doesn’t sound right…

To sum up the “reality” of what is going on, those who can should think back to the cartoon, “The Jetsons.”

George worked a grueling two hours a day! Most of that was pushing buttons, btw. That is not going to happen because business people know that the easiest way to keep wages low is to make workers compete against each other. Spacely would not have employed George (as an employee), he would, instead, have contracted out to a private contractor the button-pushing that was needed for the production line to function.

Without a fundamental shift is societal expectations, workers can expect to continually be forced into more dog-eat-dog situations. This is basic Economics 101, when supply goes up (workers), price goes down. Prior to 1977, we had a government that tried to ensure that common workers were not left behind when productivity increased. Since then…well, go google it for yourselves.

“Chrono issues have the problem that they are important in the long term, but we can ignored them for short term gain.”

If it were about economics, you would pay the professionals to stay home, accept a 70 to 80% fall in RE prices, which is really just an accounting translation, and issue a livable base plus with feedback, but the majority has been conditioned on RE for generations.

Now you see why 99% of all reorganizations just kick the can, and why all the exits are blocked with trash, like the LBOs in the IPO pipeline.

The average doctor today knows less about the disease than the patient, and both assume otherwise most of the time, and the State, which knows the least sits in judgment.

Like all politicians, Bernie has a highway for a blind spot when it comes to scientists, which are more petty than pick your ism.

To assume that scientists are not emotional, especially biologists, is not to know them.

Not the point… ke…. the methodology is not emotive…

Skippy…. ‘Science Mart’ would better unpack the reality’s…. imo

To bypass timing issues is to miss the point entirely, like diagnosing individual cancer in a sea of degeneration, and applying chemo, at the wrong time to boot.

The guy actually said he makes decisions based upon fear, after listening to scientists. And if anyone cares to look Vermont’s :-) hc policies are killing working people, not that I dislike the guy or think he is any worse than the rest.

His problem is that he suggests that he represents working people. All trump has to do is interview a few people in Vermont, who aren’t benefiting from the RE scam,

Read Science Mart and get back to me…

J&J is old money.

The Nazis were here long before that. UVM has an interesting history.

Lived Science Mart, New same as the old.

Sure we can go back to Moby Dick – the real story – and after events… yet it does nothing to change my trust nor Mirowski’s e.g. privatizing knowlage and attendant profit incentives drive the events you describe anecdotally….

From Agricultural migrant workers (transient labor forces not immigration) to Adjunct Faculty at Universities to contingency truck drivers sub-contracted against the mainstream middle class Unions; etc., the drive towards private equity financial domination is path dependent upon appropriating new resources of revenue and usurping source options from the working economy class. The fact that Harvard Professors did not look at the University situation of contingency faculty right under their own feet speaks to the blindside of establishment positions on a changing economy based upon disequilibrium from a center that still teaches a dogmatic market equilibrium.

http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2016/04/01/jobs-a01.html

Temps and contractors accounted for all US job growth since 2005

By Patrick Martin

1 April 2016

(@ Lambert Strether: Thanks for this reference: it is an absolutely essential compliment to this article, and the comments are mostly substantial and grounded in real experiences. This is a timely presentation at a critical moment of our economic based democracy.)

. “The international financial elite and its bribed political stooges are allowed to dodge taxes by stashing their wealth in offshore havens right under the noses of financial regulators, while the working class is told it must accept worsening poverty and deprivation.”

quoted from:

http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2016/04/06/pers-a06.html

Imperialism, political corruption and the real face of capitalism

6 April 2016

Quoted from: Robert Fowler and Philip Guelpa

8 June 2015

“Public and private sector workers in New York City, including transit workers, teachers and telecom workers, like workers around the country, have suffered years of stagnant and declining living standards and deteriorating work conditions, even as the stock market and the bonuses of the Wall Street bankers have reached new heights. Public and private sector workers in New York City, including transit workers, teachers and telecom workers, like workers around the country, have suffered years of stagnant and declining living standards and deteriorating work conditions, even as the stock market and the bonuses of the Wall Street bankers have reached new heights.”

Excerpted quote from:

http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2015/06/08/nurs-j08-1.html By Robert Fowler and Philip Guelpa

8 June 2015

This guy’s throwing wall pie and calling it heads.