By Ian Fraser, Twitter @ian_fraser; originally posted at his web site

Over the past few days, quite a few people have been insisting, on social media, that Britain isn’t corrupt. They’ve been claiming they see absolutely nothing wrong with Cameron describing countries such as Afghanistan and Nigeria, whose leaders were in London for the Anti-Corruption Summit in Lancaster House this week, as “fantastically corrupt”. When Cameron was caught on camera uttering these words in what he thought was a private conversation with the Queen, his clear insinuation was that their former colonial master is, by comparison, whiter than white.

On social media, many people subsequently claimed they could see nothing wrong with Cameron’s remarks. As evidence they cited Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, according to which Britain is the 10th least corrupt country of the 168 countries surveyed. Or, to be precise, Britain is ranked as the 10th= “least corrupt country”, alongside Luxembourg and Germany. By contrast, Afghanistan, where Britain fought a war from 2001-14, was ranked 166th, and Nigeria, which was a British colony until 1960, was ranked 136th.

Unfortunately, however, the methodology used by Transparency International to produce its corruption index is flawed. One issue is that it is based on subjective “perceptions” of corruption garnered from pre-existing surveys and interviews — whose very subjectivity means there’s a risk of reinforcing existing stereotypes — rather than from primary research.

Another issue is Transparency International’s somewhat narrow definition of “corruption”. Its annual survey focuses solely on whether politicians and public officials demand, and get, bribes. This follows the World Bank’s narrow definition of corruption: “the abuse of public office for private gain”.

In a recent piece in the Washington Post, Sussex University professor Dan Hough wrote:

“The Corruption Perceptions Index . . . says nothing about corruption in private business – say, the Libor scandal in Britain, or the recent VW emissions scandal in the United States. These events involve private actors, but they have very real public impacts, whether on the interest rates that people pay on their mortgages or on public health.”

In the FAQs section of its latest CPI report, Transparency International acknowledges that its approach is at best partial, stating: “The Corruption Perceptions Index is an indicator of perceptions of public sector corruption, i.e. administrative and political corruption. It is not a verdict on the levels of corruption of entire nations or societies, or of their policies, or the activities of their private sector.”

In short, TI acknowledges its index falls short of giving the full picture.

Off the scale

Even though “brown envelopes” are less ubiquitous here than they are in places like Afghanistan and Nigeria, there can be no doubt that Britain is seriously corrupt.

Even though “brown envelopes” are less ubiquitous here than they are in places like Afghanistan and Nigeria, there can be no doubt that Britain is seriously corrupt.

The failure to prosecute any of the bankers who are widely believed to have committed fraud in the run-up to the banking crisis and our so-called “two-tier justice system” are clear evidence for that. This was yesterday encapsulated by the announcement from Scotland’s state prosecutor, the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, that it had found “insufficient evidence” to press criminal charges on Fred Goodwin or other former directors of RBS, despite what is widely considered to have been the bank’s fraudulent rights issue in April 2008. That was capped by the appointment of the Lord Advocate who presided over the inquiry, or should I say “whitewash”?, Frank Mulholland, as a judge in Scotland’s top commercial court, the Court of Session.

The bailing out of kleptocratic banks with more than £1.3 trillion of taxpayers’ funds in 2008-9 without demanding or enforcing structural or behavioural change on the banking sector is another sign of, at best, “crony capitalism” and, at worst, “corruption”. One might argue that the rebranding of criminal fraud as “mis-selling” and “misconduct” is another; as is the UK government’s shameful kowtowing to the congenitally corrupt HSBC, which saw Cameron’s government last year water down much-needed post-crisis banking reforms, after Europe’s largest bank rattled its sabre and threatened to remove its headquarters from the UK.

Other signs of insidious corruption in the UK include the ability of the former prime minister, Tony Blair, to: (i) appease bankers by enfeebling City regulation, mainly in 2002-07, a period when he and fellow Labour cabinet ministers repeatedly intervened to prevent the FSA from doing its job in order to protect banks from much needed scrutiny; (ii) take a $3m-a-year senior advisory role with JPMorgan Chase within weeks of leaving Downing Street. And don’t get me started on the other roles Blair has fulfilled since 2007, including his notorious £5m deal to launder the image of Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev, a man accused of horrendous human rights abuses.

The revolving door between Westminster/Whitehall and the City of London/private sector is not the exclusive preserve of former prime ministers. Former chancellor Alistair Darling is now a director of US banking giant Morgan Stanley and former chief secretary of the Treasury Danny Alexander, who lost his Inverness, Nairn, Badenoch and Strathspey parliamentary seat in the May 2015 general election, is now vice-president and corporate secretary of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. And of course another former Labour prime minister, Gordon Brown, last December joined the global advisory board of Pimco, the world’s largest bond fund manager.

According to a piece in the Daily Mail these four are just the tip of the iceberg. Nearly 400 former government ministers and senior civil servants have, since 2008, cashed in on their experience of government in order to pass through the gilded revolving door into lucrative private sector and regulatory jobs. The revolving door also works in the other direction with, for example, Stephen Green, former chairman of HSBC, ennobled by Prime Minister David Cameron so he could become a trade minister. As the door has spun at warp speed, so the scope for corruption has intensified.

Attempted cover ups

There are plenty of other signs of institutional corruption in the UK, including the appalling Hillsborough cover up and the Tories’ attempted cover up of alleged election fraud related to money spent on ‘battle buses’ during last year’s general election campaign, a matter which is now being criminally probed by more than ten police forces.

Then there’s the captured and atrophied state of our financial regulators, a situation which still gives banks and other financial institutions more or less free rein to fleece their clients at will, without fear of retribution; the leeway and credence given to “Big Four” accountancy firms even though, by their own actions, they have shown themselves to be useless and corrupt; the way in which almost every UK inquiry the audit and other failures of PwC, KPMG, Deloitte and EY either never really happens or ends up getting suppressed; and the way in which Tony Blair succumbed to bullying by the Saudis to drop the Serious Fraud Office’s probe into BAE Systems bribes associated with Al Yamamah, the $150 billion arms deal between Britain and Saudi Arabia (see my earlier blog Britain Is Fast Turning into a Banana Monarchy and Geoff Gilson’s blog).

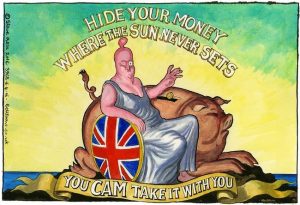

I would single out the recent failure of David Cameron’s government, despite the revelations contained in the Panama Papers, to force Britain’s Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies, which include the British Virgin Islands, and indeed the City of London itself, to become more open and transparent and to cease acting as a hiding place for tax evaders, money launderers, drugs barons, fraudsters and corrupt politicians to stash their ill-gotten gains as the most glaring recent example of corruption.

The governments of Nigeria, Kenya, France and Afghanistan all recently committed to providing public registers of the beneficial ownership of companies, trusts and foundations. But the UK’s tax and secrecy havens are refusing to make any such commitment and Cameron has no intention of forcing their hands.

Dirty money from tax evading oligarchs and other nefarious individuals is inflating London’s property bubble (in the process turning the capital into even more of an unlivable city for ordinary mortals) at the same time as adding what is perceived to be much needed liquidity to the London’s financial markets. However in welcoming it , we’re effectively giving a “getaway vehicle” to international gangsters. In the process we’re fuelling international crime, war and terrorism and depriving developing countries including Russia, China and India of hundreds of billions of dollars that is rightfully theirs.

None of this would be possible were it not for the UK’s notoriously feeble anti-money laundering defences.

In its excellent “Don’t Look, Won’t Find” report, Transparency International highlighted how so-called professionals in banking, accountancy, law, estate agency and company formation — as well as direct sellers of products and services to wealthy foreigners including auction houses, purveyors of luxury goods and private schools — are ushering in this toxic tide. Most of the 22 regulators that are supposed to stem the flow of “dirty money” into the UK were revealed to be far more interested in cheerleading and lobbying for their member firms (which of course make huge sums from laundering dirty cash) than in regulating them. Such self regulation has become an utter farce.

Scotland’s company factories

The situation in company formation is particularly worrying. Anyone from anywhere in the world can set up an opaque UK registered Limited Partnership (shell company) for a relatively small fee, on a no-questions-asked basis.

Companies House admits that verifying the identities of those who incorporate such vehicles, or checking whether they have legitimate intent, are outside its remit. Last summer Richard Smith and I, when researching the role of Scottish limited partnerships in a $1bn Moldovan bank fraud, discovered that such vehicles are now widely recognised as “Europe’s secrecy vehicle of choice” and are widely favoured by organised criminals, tax evaders, fraudsters and money launderers.

Today these secrecy vehicles are being churned out at a rate of 6,000 a year (up from 500 a year in 2008) by “company factories” based in a twilight zone of modest ex-council flats in housing schemes in places like Edinburgh and Inverness. We found that a single ground-floor, one-bedroom flat located in the neighbourhood where Irvine Welsh set Trainspotting (pictured left), was not only home to two company formation businesses —Royston Business Services and Arran Business Services — but was also the registered address of 425 companies. One of the firms based in the flat, Fortuna United LP, was, according to investigators Kroll, pivotal to a $1bn bank fraud which has devastated Moldova’s economy and caused the collapse of the former Soviet republic’s government.

Today these secrecy vehicles are being churned out at a rate of 6,000 a year (up from 500 a year in 2008) by “company factories” based in a twilight zone of modest ex-council flats in housing schemes in places like Edinburgh and Inverness. We found that a single ground-floor, one-bedroom flat located in the neighbourhood where Irvine Welsh set Trainspotting (pictured left), was not only home to two company formation businesses —Royston Business Services and Arran Business Services — but was also the registered address of 425 companies. One of the firms based in the flat, Fortuna United LP, was, according to investigators Kroll, pivotal to a $1bn bank fraud which has devastated Moldova’s economy and caused the collapse of the former Soviet republic’s government.

At least 90 per cent of the Scottish limited partnerships churned out by these “company factories” have anonymous general and limited partners (corporate “beneficial owners”) located in offshore secrecy jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, Marshall Islands, the Seychelles, Belize and Panama. Fortuna United was controlled by two firms purportedly based in the Seychelles — Trafford United Ltd, where the flat’s owner Viktoija Zirnelyte is the sole director, and Brixton Ventures Ltd, where her fellow Lithuanian Remigijus Mikalauskas is the sole director.

Scottish limited partnerships such as Fortuna United — whose opacity is so impregnable it’s virtually impossible to verify the purpose to which they are being put, who controls them or the sums being channelled through them — are also being marketed by dozens of outfits across Central and Eastern Europe including Gestion Baltic, Inlat Plus and Darwin Tax, all based in Riga.

If it was not for ready availability of anonymous shell companies registered in supposedly reputable tax havens and jurisdictions such as the UK, time could be called on the offshore game. Without them, the corrupt would be unable to loot developing counties without leaving fingerprints, and western firms allegedly including Rolls-Royce, Petrofac and Weir Group would have no anonymous conduits with which to grease the palms of overseas officials and politicians in the hope of securing lucrative contracts. In her excellent BBC Radio 4 ‘File on 4’ documentary on the Unaoil scandal first broadcast on 15 May 2016, ‘Dirty Oil’, Jane Deith revealed how UK based shell companies, including Comex Industries LLP, were being allegedly being used by Monaco-based Unaoil to funnel bribes to, among others, Iraqi politicians.

But despite all the recent grandiloquent claims from David Cameron, neither the British nor the Scottish government seems willing to do anything to address this particular open sore, as the revised beneficial ownership rules he keeps trumpeting do not apply should Limited Partnerships that have overseas general partners and limited partners. If you can face reading more on some of the uses to which Scottish LPs are being put, I’d recommend A billion-dollar bank fraud in Moldova, and 20,000 opaque British corporations (by Richard Smith and me) and The billion dollar ex-council flat (by the BBC’s Tim Whewell).

David Whyte, professor at the University of Liverpool, recently produced a comprehensive guide that includes other examples of serious corruption in the UK. Editor of the book How Corrupt Is Britain?, Whyte summed up the situation in an earlier interview given to Afshin Rattansi of RT’s Going Underground. In the interview, Whyte said:

“We have a national myth that Britain is not corrupt . . . There’s an almost racist assumption that Britain is not infected by corruption . . . in banking, the SFO only prosecutes about 20 cases a year, but there are around 40,000 burglaries that end up with prosecutions each year . . . we have a problem of impunity and a problem with institutions which are unable to hold the powerful to account.”

Still at least we’re in the world’s top ten least corrupt countries — according to Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index anyway.

Responding to Cameron’s gaffe, Cobus de Swardt, managing director of Transparency International, said:

“There is no doubt that historically, Nigeria and Afghanistan have had very high levels of corruption, and that continues to this day. But the leaders of those countries have sent strong signals that they want things to change, and the London Anti-Corruption Summit creates an opportunity for all the countries present to sign up to a new era. This affects the UK as much as other countries: we should not forget that by providing a safe haven for corrupt assets, the UK and its Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies are a big part of the world’s corruption problem.”

Re the corruption evident at the Nevada democratic convention.

A good friend more than once admonished that;

That bit of wisdom is based on the following event, as explained at the explore Pennsylvania history web site;

If number 10 (Corruption Perceptions Index) successfully deals with number 166 for 14 years – could that mean that 10 did so at number 10 level or 166 level?

This article made me curious about the corruption in Canada and all I had to do was read Wikipedia on Corruption in Canada and, lo and behold, we too are corrupt. But I noticed that the banking sector wasn’t mentioned as one of the places where corruption has occurred and we know that the banks in Canada were bailed out for making bad business decisions yet the regulations governing their behaviours have not changed and the huge salaries of their CEOs continue onward and ever upward. For sure, Transparency International’s definition of corruption is far too narrow (essentially “taking bribes”) and the world’s perception of corruption is a lot more distorted than the real picture, I’m sorry to say.

A better definition would include all the synonyms too: “dishonest or fraudulent conduct by those in power, typically involving bribery . . . .

. . . dishonesty, unscrupulousness, double-dealing, fraud, fraudulence, misconduct, crime, criminality, wrongdoing.”

So perhaps it is true that one-half of the world exists to make the other half of the world miserable.

“Transparency International ……. focuses solely on whether politicians and public officials demand, and get, bribes.”

I think that is right. I cannot really imagine another way to establish the state of corruption in any country. Our ancient saying is “put an honest man in charge and everyone is more or less honest; put a crook in charge …….” TI focues on the men in charge. Its staff may not all be perfect but their overall performance and reporting is a global plus.

Business corruption is another matter. Its endemic everywhere. We cannot deal with that, even if we really wanted to, until governments are honest. Prioritize.