By Eric Tymoigne, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Economics at Lewis and Clark College and Research Associate at The Levy Economics Institute. His research expertise is in: central banking, monetary economics, and macroeconomics. Originally published at New Economic Perspectives.

The following answers a few question in order to illustrate the previous post and to develop certain points.

Q1: Can a commodity be a monetary instrument? Or, does money grow on trees?

Let us tackle the idea that “gold is money”. Clearly, a gold ingot is not a monetary instrument. There is no issuer, no denomination, no term to maturity or any other financial characteristics. A gold ingot is just a commodity, a real asset not a financial asset. On the other hand, gold coins have been monetary instruments and are still issued at times (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Gold (ingots) vs. Gold Coin (2009 $50 American Buffalo Gold Coin)

Similarly, it is incorrect to state that “salt was money” because salt is a commodity that embeds no promise; however, Marco Polo noted that in the Chinese province of Kain-du:

There are salt springs, from which they manufacture salt by boiling it in small pans. When the water is boiled for an hour, it becomes a kind of paste, which is formed into cakes of the value of two pence each. […] On this latter species of money the stamp of the grand khan is impressed, and it cannot be prepared by any other than his own officers. Eighty of the cakes are made to pass for a saggio of gold. But when these cakes are carried by traders amongst the inhabitants of the mountains, and other parts little frequented, they obtain a saggio of gold for sixty, fifty, or even forty of the salt cakes, in proportion as they find the natives less civilized.

It seems that salt cakes issued by an emperor (“grand khan”) might have circulated as monetary instruments. However, a lot of details are missing from this description:

- What were the unit of account and face value? (definitely not the pound, it is China)

- What was the term to maturity? Were the cakes accepted in payment at any time by the emperor?

- What were the means for the emperor to make the previous financial characteristics a reality? I.e., what were the reflux mechanics? Did the emperor levy dues that could be paid with salt cakes at par? Did the cakes provide conversion into something? Etc. Bearers need to be convinced so trust about the issuer must be established.

- The bit about the amount of gold that salt cakes could buy is irrelevant. Polo is just telling us that a commodity (gold bullions) was cheaper in the mountains. He might as well have told us about how different the price of apples and potatoes are in different parts of the country.

The broad point is that monetary instruments can be made of a commodity but that commodity itself is not a monetary instrument. We all know the expression “money does not grow on trees.” Monetary instruments are not a natural occurrence and for a commodity to become a monetary instruments some specific financial characteristics must be added: a unit of account, a face value, a term to maturity, among others. All this requires an issuer who promises to implement these financial characteristics.

Say a goldminer wants his gold nuggets to be a monetary instrument, for that to be the case the goldminer must promise:

- To distinguish his gold nuggets from other gold nuggets

- To declare what their face value is in terms of a unit of account

- To implement that face value by promising to take back at any time the gold nuggets in payments at the stated face value.

Now the third condition introduces a problem because it means that the goldminer must be willing to be paid in gold nuggets for his gold nuggets. I let you ponder on that.

Q2: Can a monetary instrument be a commodity?

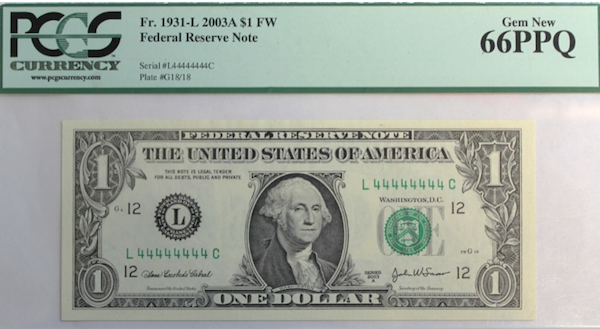

Yes. Numismatists are specialists at treating current and former physical monetary instruments as commodities by determining the price of banknotes and coins in terms of their rarity, peculiarity, etc. For example the $1 FRN in Figure 2 is worth $1200 currently because of its peculiar serial number. But that is not its fair value as a monetary instrument. If one buys this note and goes to a store or to a government office, the person to whom one hands the note will only take it for $1. The same applies to the buffalo gold coins above. One can use them to pay debt owed to the government but only $50 worth, not more nor less, even though the coin is worth thousands of dollars as a collectible item.

Figure 2. A $1 FRN worth $1200 as collectible items

Source: here

The same applies also to gold and silver certificates. Here is how the U.S. Treasury puts it:

Although gold certificates are no longer produced and are not redeemable in gold, they still maintain their legal tender status. You may redeem the notes you have through the Treasury Department or any financial institution. The redemption, however, will be at the face value on the note. These notes may, however, have a “premium” value to coin and currency collectors or dealers. (U.S. Treasury)

One can redeem them at the Treasury (to pay debts owed to the Treasury or to get Federal Reserve notes) or deposit them at banks, but only at face value. That is their value as monetary instrument. Their value as a commodity is sometimes much higher.

Finally, a fun example is the current case of the penny, which brings us back to darker times of monetary history (see next post). A while back, National Public Radio ran a segment on penny hoarders. These are people whose hobby is to hoard pre-1982 pennies. Some even go to their local banks and ask to convert dollar bills into pennies and then spend their evenings triaging boxes of pennies. Why would they do that would you ask? Pre-1982 pennies are made mostly of copper and, given that the price of a pound of copper tripled over the past ten years, the face value of a penny is half the intrinsic value (i.e. value of the content of copper): face value is 1 cent, intrinsic value is 2 cents, 100% profit from selling pennies for their copper content! Currently, there is one small problem with this portfolio strategy: It is illegal to destroy government currency. However, the government is considering the possibility of demonetizing the penny coin because it costs more to make than its face value, and because US residents mostly find it cumbersome to use. If the government ever demonetizes the penny coin, penny hoarders are ready to rush to their local scrap metal dealers.

Q3: Is money what money does?

Francis Amasa Walker concluded in the late 19th century that “money is what money does.” This has been an extremely influential way of analyzing monetary systems is many different disciplines: economics, anthropology, law, among others.

It is used in a narrow way by economists who use the Real Exchange Economy framework and who focus on the function of medium of exchange. In order to avoid the problem of double coincidence of wants induced by barter (Joe has apples and wants pears, Jane has pears but wants peaches), a unique commodity was progressively sorted out as best for market exchanges. Thus, a monetary system can be detected by checking for the presence of a medium of exchange. Anthropologists, among others, reject this narrow functional approach. In primitive societies, exchange was not done principally, or even at all, for economic reasons and so the nonexistence of a double coincidence of wants was not a problem. The broad functional approach classifies anything as monetary instrument as long as it performs all or parts of the functions attributed to monetary instruments. The distinction between “all-purpose money” and “special-purpose money” follows.

A main issue with the functional approach is that it does not explicitly define what “money” is, which creates several issues:

- Inquirers may pick and choose depending on the circumstances, which may lead the inquirer to impose inappropriately his own experience to explain the inner workings of completely different societies.

- Inquirers may tend to assume that monetary instruments must take a physical form when they may be immaterial.

- Inquirers may exclude things that are monetary instruments but are not used for any of the functions. Collectible coins and notes are monetary instruments as long as the issuer does not demonetize them.

More broadly, too much emphasis will be on detecting things that fulfill the selected function and not enough effort will be devoted to a detailed account of the unit of account used, how the fair value was determined and if it fluctuated, how the reflux mechanisms were implemented, etc. The example of the salt cakes above is an illustration of that point. Just noting that something is used as medium of exchange or means of payment, and moving on to something else, is a poor means to perform monetary analysis.

This approach also creates difficulties to convincingly include “money” in models, and pushes to ignore the financial side of the economy and the role of nominal aspects. Monetary instruments are mere commodities and do grow on trees—there are fruits—and all debt payments are denominated in fruits.

Finally, inquirers using this approach may confuse monetary payments and in-kind payments, may assume that there is a monetary system where there is none, may make a truncated analysis of monetary systems consisting mostly in a mere recollection of objects, and may miss the presence of a monetary system. For examples, by relying on the words of an Arab merchant and an Arab historian of the 9th and 10th century, Quiggin reports that more than a thousand years ago cowry shells:

formed the wealth of the royal treasury […] [and] when funds were getting low, the sovereign sent out servants to cut branches of coconut palm and throw them into the sea. The little mollusks climbed on to the branches and were collected and spread out on the sand to dry until only the empty shells were left. So the royal bank was filled again. Ships from India brought goods to the Maldives and took back millions of shells packed up in thousand in coconut palm leaves. It was a profitable trade, for even in the seventeenth century we hear of 9,000 or 10,000 cowries being bought for a rupee and sold again for three or four times as much on the mainland of India. (Quiggin, 1963, 25-26)

However, from this description, one cannot conclude that cowries were monetary instruments used by the king to finance the purchase of foreign goods and services. Indeed, it is not explained what the unit of account of the Maldives was and how cowries were monetized, i.e., who, if anybody, issued them as financial instruments (did the royal authority issue them and was the royal bank ready to accept cowries in payment?), and what was their relationship relative to the unit of account. In addition, the role of cowries as monetary instruments is doubtful for the Maldives because, cowry shells were worth nothing against goods “except by shipload” (Polanyi 1966, 190)—an extremely inconvenient means of payment and medium of exchange. What one can conclude from the description is that the Maldives authorities were involved in the trade of cowries with Indian and Arab merchants. They were exporting cowries against imports of other goods—a situation of bilateral trade, not a situation of cowry monetary system.

Q4: Are contemporary government monetary instruments irredeemable? Or, is the fair value of contemporary government monetary instruments zero?

No. A WELL-FUNCTIONING MONETARY SYSTEM REQUIRES THAT ALL MONETARY INSTRUMENTS BE REDEEMABLE. Federal Reserve notes are redeemable, silver certificates are redeemable even though they are no longer convertible (see the Treasury in Q2), and bank accounts are redeemable. They are redeemable as long as they can be returned to the issuer, hopefully at their initial face value. They can be returned to the issuer through two channels:

- Bearers demand conversion into something else at a given rate: government currency for bank accounts, foreign currency for government currency, etc.

- Bearers pay the issuer with the notes: governments take their currency is payment of dues owed to them, as do banks. The payment allows the bearers to avoid jail time and other legal problems.

So to be redeemable a monetary instrument does NOT have to be convertible. As such the fair value of a monetary instruments, its net present value, is face value.

In the past, some governments did forget to include, or removed, a redemption clause:

Paper money has no intrinsic value; it is only an imputed one; and therefore, when issued, it is with a redeeming clause, that it shall be taken back, or otherwise withdrawn, at a future period. Unfortunately, most of the governments, that have issued paper money, have chosen to forget the redeeming clause, or else circumstances have intervened to prevent their putting it into execution; and the paper has been left in the hands of the public, without any possibility of its being withdrawn from circulation (Smith 1832, 49)

Probably, no government paper money was ever sent forth which was not expected to be redeemed in full value, at some time, although that might be distant. […] Nevertheless, the issues of government money that have not been redeemed, or the payment of which has been either formally or tacitly renounced, have been very numerous. (Langworthy Taylor 1913, 309)

In that case, the fair value of a monetary instrument is indeed zero because its term to maturity is infinity which means that its fair value is:

P = C/i

Given that no coupon was paid, then P = 0. But this does not apply today because monetary instruments are redeemable on demand by bearers at a very stable face value.

All this does not seem to be well understood. For example, recently Adair Turner wrote (and he is far from the only one to have said so):

Monetary base is an asset for the private sector, but for the government it is a purely notional liability (with NPV equal to Zero) since it is irredeemable and non-interest-bearing. (Turner 2015)

This confuses irredeemable and unconvertible. The monetary base is redeemable. This point of view also raises other problems:

- Remember that balance sheets are interrelated so if a financial liability is worth zero in one balance sheet, then a financial asset must be worth zero in another balance sheet. Turner makes an accounting error.

- Why would the private sector be willing to hold something that is worth zero? There is no benefit that comes from accepting a monetary instrument, not even avoiding prison because taxes cannot be paid with government monetary instruments.

- If valued at zero then balance sheets should record a large loss of assets (and net worth) for banks, firms, and households: Your savings are worth nothing in nominal terms!

Q5: Is monetary logic circular?

No. The acceptance of a monetary instrument by anybody ultimately rests in the confidence in the issuer, not in the confidence that other potential bearers will accept.

Q6: Do issuers of monetary instrument promise a stable purchasing power?

No. If that was the case, issuers of monetary instrument would have defaulted on their promise continuously since the beginning of financial times. They never were able to provide a stable purchasing power, even less so since the end of World War Two. As such the demand for monetary instruments would be nil if a stable purchasing power was a promise embedded in monetary instrument because the creditworthiness of the issuer would be nil.

A stable purchasing power is not a promise of any issuer of monetary instruments. This is fine for most bearers as long as the purchasing power of monetary instruments is relatively stable in the short-term. If one wants something that holds purchasing power over the medium to long run, then one should switch to other assets.

Q7: Are monetary instrument necessarily financial in nature?

Yes, remember: “money does not grow on trees.” While monetary instrument can be made of a commodity that commodity does not tell us anything about the monetary nature of a thing. A gold coin is a monetary instrument not because it is made of gold but because of its financial characteristics. Gold is a collateral embedded in the coin. Similarly a house is not a mortgage, a house is a collateral for a mortgage and nothing can be learned about the inner workings of mortgages by studying how a house is made.

The “primitive moneys” would need to be studied much more carefully to determine if some of them were monetary instruments. Just checking if they passed hands in exchange of goods and services, if they were used to pay for a bride, etc. is a poor means of determining the “moneyness” of something given that one cannot make a difference between in-kind payments and monetary payments. We saw above that cowry shells were not monetary instruments in the Maldives but they were in Africa and detailed analysis has been done to establish that fact.

Q7: Are credit cards monetary instruments? What about pizza coupons? What about pretend-play banknotes and coins? What about bitcoins?

No to all questions.

A credit card is not a financial instrument—it does not have a maturity (issuers of credit cards do not accept credit cards in payment) and it is not related to a unit of account (it is not a carrier of the unit of account). The underlying credit line is not financial instrument either. The line represents the maximum amount of a customer’s promissory note (called credit card receivables) that a credit company is willing to take on its balance sheet.

Say that household #1 wants to get a credit card from Bank A. #1 fills up the required documentation so A can check #1’s creditworthiness. #1 is approved by A and gets a $1000 credit line. Where is that recorded on the balance sheet? Nowhere, it is an off-balance sheet item. The line is just saying that A will take on its balance sheet up to $1000 of #1’s promissory notes without asking again to check #1’s creditworthiness. We saw in a previous post what happens when a credit line is used: A’s assets rise by the amount of line drawn by #1, #1’s liabilities rise by that same amount.

What about a pizza coupon? It has an instantaneous maturity (one can go to the pizza shop at any time to claim a pizza), it is a convertible, but it not a financial instrument because it does not involve monetary payments but merely in-kind payments: it converts into a commodity. If the coupon could be used to pay debts owed to the pizza shop at any time, if the pizza shop stated at what value it would take the coupon in payments, then it would be a monetary instrument.

Figure 3 shows a set of play notes that my son got with his cash register. In order for the notes to become monetary instruments, the company that created them would need to do the following:

- Change the design: too close to the design of Federal Reserve notes even though it is a crude imitation. Definitely “The United States of America” should be eliminated because they are not issued by the government.

- Promise to take the note in payments: Bearers can pay the company with the notes to buy things from, and clear debts owed to, the company.

Finally, bitcoins do not have any issuer and are irredeemable. The first problem prevent them to be a monetary instrument, the second problem makes them valueless as monetary instruments. Bitcoins are commodities/real assets, not financial assets.

Figure 3. Pretend-play monetary instruments

Q8: Errors made in past monetary systems

Given the characteristics of monetary instruments, they should circulate at parity all the time; however, actual circulation at par does not define a monetary instrument. Par circulation is only the result of the inner characteristics of a financial instrument, together with the existence of a proper financial infrastructure that allows these characteristics to be expressed in the fair value. Only recently has there been well-functioning monetary systems. They are not without problems but in general they ensure a smooth processing of payments and can be used as a reliable medium of exchange, both of which help to promote economic prosperity to some extent.

For reasons related to poor technics of production, inexperience, political instability, frauds, and poorly developed banking systems, it took quite a long time for the proper characteristics and infrastructure to be established to have a smoothly running monetary system. Here are some errors that were made along the way:

- No stamped face value: In the Middle Ages, King cried up or down (i.e. changes by decree) the face value too many times.

- What is the problem? Nobody had any idea what face value was: “there were so many edicts in force referring to changes in the [face] value of the coins, that none but an expert could tell what the [face] value of various coins of different issues were, and they became highly speculative commodities” (Innes 1913, 386).

- Free-coinage: Anybody with gold can go to the mint and get coins stamped out of ingots (government keeps a portion of the ingots: seigniorage)

- What is the problem? Kings legalized counterfeiting. Anybody with gold could issue a debt of the king, i.e. make the king liable. Today, in the United States, an equivalent would be for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to print Federal Reserve notes for anybody who comes with paper that respects the Bureau’s specifications

- No redeeming clause: There is no way to return to the issuer its monetary instruments

- What is the problem? Fair price is zero unless there is a collateral or recourse, which is not the case for monetary instruments made of paper.

- There is a redeeming clause but no actual means to implement it because no payment is due to issuer (e.g., sometimes taxes during the time of colonial bills were not implemented when they were supposed to be), or conversion is very difficult (banks during wildcat era).

- What is the problem? The term to maturity is no longer instantaneous as promised but depends on the expectations of bearers. As such the discount factor comes back into the valuation of the fair price and so the fair price is unstable and varies with confidence of bearers about the issuer.

- Full-bodied coins: At issuance the face value (FV) is the same as the market value of the gold content (PgG with PG the price of gold per ounce and G the ounces of gold in the coin)

- What is the problem? if ∆Pg > 0 => PgG > FV => coins disappear from circulation (melted into ingot or exported as commodities)

- Lack of a proper interbank payment system: in that case interbank debts are difficult to clear and settle. This creates all sorts of problems going from delays in processing payment, to loss of purchasing power because some bank monetary instruments trade at a discount relative to other bank monetary instruments, to full blown financial crisis because payments cannot be processed and so creditors do not receive what they are owed and in turn cannot pay their own creditors.

Q9: Do legal tender laws define monetary instruments? What about fixed price?

Legal tender laws state that, in court settlements, creditors must accept whatever is defined as legal tender in payments of what is owed to them. Creditors cannot refuse payments with something that is legal tender. This does not mean a legal tender cannot be refused during petty transactions. The current legal tenders in the US are Federal Reserve notes but plenty of shops and government offices refuse cash payments.

Something that is legal tender is not necessarily a monetary instrument. In the past commodities such as tobacco leafs have been included in the legal tender laws, forcing creditors to accept payments in kind. The next post will develop the case of tobacco leafs in the United States, which came about because of a shortage of monetary instruments.

Something that has a fixed price is also not necessarily a monetary instrument. It may just be a commodity managed by an economic unit.

Q10: Is it up to people to decide what a monetary instrument is? Who decides when something is demonetized?

The public opinion about what is or what is not a monetary instrument does not matter and popular belief by itself cannot turn something into a monetary instrument. To take an analogy, one can use a shoe to hammer nails but it does not make the shoe a hammer. The fact that everybody thinks that shoes are hammers does not turn the shoe into a hammer. If everybody is delusional enough to believe the contrary, there will be many more work-related accidents and productivity will drop because shoes are not built properly to hammer nails. In a similar fashion if everybody wants to believe that gold nuggets, tobacco leafs, or grains of salt are monetary instruments, the payment system will not work smoothly and economic activity will suffer.

As explained in Q2, some monetary instruments are used merely as collectible items. Some persons may also use monetary instruments as ornaments and for other non-economic uses. These other uses do not demonetize a monetary instrument. That can only happen if a monetary instrument seizes to be a promise and that is up to the issuer to decide.

Q11: Can anybody make a monetary instrument?

Yes as long as one does not counterfeit existing monetary instruments, one can do so. Good luck getting it accepted.

Done for today! Next is the final post of the series: Monetary history.

With respect to your answer to Q5, I submit this: http://andolfatto.blogspot.ca/2011/08/fiat-money-in-theory-and-in-somalia.html

So it seems there is some evidence to suggest that confidence in the willingness of others to accept can be important.

There is also modern monetary theory, that states that the value of the currency ultimately depends on its ability to settle taxes.

That is an interesting read, will use it for part 17 of the series. I would be careful to use cases of chaos and monetary disorders like this to establish anything about what goes on in monetary mechanics. Finance is full of “strange” cases (the last one is negative i) that occur at odd times and can be explained away with the peculiarities of the time. In case of stable monetary system the evidence is strongly in the camp of issuer being central (that issuer can be a state or a private entity, see part 15 at New Economic Perspective).

Now going back to the paper, what goes on in Somalia can be explained using the framework of part 15 (go to New Economic Perspective, the current post here is part 16)

1- the state was central at establishing the trust about the currency. That’s what anchored the expectations about the face value of the somalian shilling.

2- Given the confusion during the time the state collapsed, citizens just relied habits, anchoring induced by “inertia provided by historical acceptance” created by state.

3- If citizens believe that collapse of state is only temporary and shilling will be reissued later then there is an incentive to continue using it. Very different from the case of the transfer to Eurozone when states spent years educating and informing their population about the demonetization of their currency, and gave a clear date about when demonetization would occur. In Somalia, everybody was left in the dark.

4- The belief that shilling would be again the national currency was reinforced by two aspects: a) local governments did accept them as taxes payment at least temporarily (contrary to authors I would not brush this away as irrelevant) b) “armed militia” that substituted for government, started to issue the shilling and, in addition, may have allow dues to be paid in that currency (not developed in paper)

All this reminds me a bit of shares that continue to trade even as a company goes through liquidation and reorganization. People are hopeful that the company will come back and be great again. Same can be said here, people hope that the government would come back and accept the shilling back again.

No rabid comments yet? I’m surprised.

I like ‘Gold is a collateral embedded in the coin’.

Did I miss something, or is this all about M1 money, which is only a tiny fraction of the actual “money” circulating in the system? US cash and coin is numbered in the billions, but the total amount of money on deposit is in the trillions. I may not have picked it up, but this discrepancy seems to say something rather important about money, and I don’t think this article addressed it. I’m more than welcome to be corrected, as these discussions always leave me with an impression of mumbo-jumbo and the logic may simply not be my logic.

Good question. I think this relates to Das’s idea of cotton candy.

In his book ‘Extreme Money: Masters of the Universe and the Cult of Risk’ (2011) Satyajit Das talks about the ‘Liquidity Factory’.

On an inverse pyramid at the bottom little pinnacle are the central banks, 2%, then there are bank loans, 19%, then securitized debt, 38% and then derivatives 41%.

The 2% is the $16 trillion pool of Treasuries. This is the high powered money that backs up or is the foundation for the rest. This is financialization run amok and what he calls ‘cotton candy’ which is spun sugar composed mostly of air.

This is all considered liquidity, the lubricant that allows the global economy to run. 79% of it is derivatives and securitized debt which are largely unregulated and full of fraud. The $16 trillion of US Treasuries used as collateral to back it all up is a small fraction.

This is financialization run amok and what he calls ‘cotton candy’ which is spun sugar composed mostly of air.

If US Treasuries continue to support cotton candy they will lose their validity as a global reserve currency.

——————

I think this gets into leverage, fraud and the idea of ponzi finance which Eric dealt with more in installment 14.

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2016/05/money-banking-part-14-financial-crises.html

The house of cards that we’ve built can’t be used to satisfy payments we must make such as taxes and I think this is what some people refer to as a liquidity crisis in our current situation with these products such as derivatives.

This is called “money multiplier” and has been discredited.

The Orthodoxy has a problem. They argue that banks do not create money (what the Heterodox calls “androgynous money”) and simply serve as clearing houses between barrowers and savers. If that were true, then lending can not lead to economic growth as the total sum of money couldn’t change through lending process.

The Orthodoxy needed an explanation how lending could have an expansionary effect on the economy – while still not expanding the money supply, hence money multiplier.

We now know that banks do create money, vast sums of it in fact.

This is not new and banks did this all the time in the past – but by issuing their own instruments. Now however, the banks are permitted to create US credit which is indistinguishable from the credits issued by the Federal Reserve.

Excellent addition to an excellent summary by the OP.

This “excellent” summary is also incorrect.

“for a commodity to become a monetary instrument some specific financial characteristics must be added: a unit of account, a face value, a term to maturity, among others. All this requires an issuer who promises to implement these financial characteristics”.

Um, no.

Unit of account: weight, which is not a unit that must be “added”, it’s already in universal and accepted use: 1 gram, 100 grams, etc

Face value: not required.

Term to maturity: Gold has no “term to maturity” and does not require one. That’s the point.

Others? Such as?

Requires an issuer: No. Requires a refiner and a set of standards for fineness, physical appearance, custody and handling. Already in place.

We’ve been in the thrall of debt-based money since 1640, now it’s the only form of money people can see even when other forms are right under their noses.

Apply the above requirements to cowrie shells (widely acknowledged as one of the longest-lived and widely-used forms of money) and you end up with the same conclusions.

Cowries are great examples of monetization process. The one on the beach were not monetary instrument. States monetized them by linking them to a unit of account (sometimes also named cowry) differentiating them from beach cowries (via stringing, coloring, etc), defining a face value (which was cried out instead of marked, like mediaeval coins), taxing them at par in tax payment.

All monetary instruments are a liability of someone since the beginning of reliable records (3000bc).

So no gold nuggets/bullions/ingot are not monetary instruments and have never been so to my knowledge (always happy to get some counter evidence)

I think you’ll find that that’s “endogenous” money, not “androgynous”; i.e. money that is created from within the system, as opposed to money injected from the outside (QE)–not money that is ambiguously gendered….just sayin’ ;-)

Oh, thanks for that. I stand corrected on both counts. (Always kind of wondered why gender came into it.)

There is a “money multiplier”. No , it has not been discredited, at least any more than new math has been discredited. It is a mathematical property of the fractional banking system. Along with it is a “velocity of transactions”. One caveat to keep in mind is “your mileage may vary”, if you can wrap your head around the implications there.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_multiplier

What Code has in mind is the money multiplier theory, that reserves cause money supply. That has been discredited. The causality is reversed and there is a money divisor

I’d maybe explain it as “bankers cause money supply”. We also had Marriner Eccles chime in with his “pushing on a string” corollary and Keynes with the more intellectual “Liquidity Trap”.

A math equation can not have cause and effect. There is no “agency” in a math equation. It is quite silly to say one core component of a model of our vastly more complicated financial system has been “discredited” because a single math equation has been running the world incorrectly.

So, credit creation[magic drawn from the future] can drop due to banks not lending, and the velocity of money can drop from people, corporations and/or governments not spending. In reality, each bank is regulated on capital ratios – which may put a upper limit on credit creation. Then we have zero reserve banking too in some countries – so they are allowed to lend out every penny they get there hands on by whatever nefarious means they can devise in our modern financial system that no one fully understands. In this case, depositors can lose 100% their money instead of only 90% or so, and I would guess they would be at least marginally more concerned that banking regulators are doing a good job.

Why the math fixation? Either way, math doesn’t qualify as evidence. As the your wiki link points out in the next paragraph, the Bank of England and Standard & Poors have both directly refuted these claims with factual evidence.

It might surprise you to know that in science, evidence actually trumps math. Meaning that even if you could show me with 100% certainty that something to be mathematically true, evidence can still prove it to be wrong. And yes, this does happen in physics. Just about the entire field of quantum mechanics is counter intuitive. (The joke is that if you understand quantum mechanics, than you don’t understand quantum mechanics.)

My understanding of fractional reserve banking is that it consist mostly the proposition that currency doesn’t need to be backed by precious metals or stones to have monetary value.

As I said before, money multiply is at its base the argument that banks do not expand the money supply through lending. Banks only lend from existing reserves of cash given to them by the depositors. The argument goes that the fed delivers $100 to the bank; the bank lends it out some ratio to customer A. Customer A spends that money for customer B who then deposits it back at the bank. The bank then lends out a ratio of THAT money out again to customer C, creating M2 money, who spends it on customer D, who then deposits that money into the bank. The bank lends it out again, creating M3 and so on to M4, M5, and so forth until the ratio leads to come to some quantity of money that can no longer be loaned out.

We know this to be wrong for several reasons. 1) It confuses a stock with flow. The amount of money from lending remains the same at each stage of the transaction, and their by limiting the scale of the economy. 2) Banks do not lend from reserves. They lend from nothing, and then restore their reserves later. 3) Banks no longer keep significant deposits, begging the question of where it is they are supposed to get their money from in order to lend.

This means that banks DO expand the money supply through lending. And by extension the amount of expansion is correlated to privet debt. And when that privet debt fails – the money supply undergoes radical deflation – which is precisely what happened in 2008.

Regarding Code name D’s statement:

“It might surprise you to know that in science, evidence actually trumps math. Meaning that even if you could show me with 100% certainty that something to be mathematically true, evidence can still prove it to be wrong.”

I don’t know where D got this idea, but as a physicist I’ve never heard of math and physics ever being in conflict. Math is just an application of logic, rules, and definitions to a set of axioms to develop a theory. If axioms are in conflict, one finds logical contradictions and must change the axioms to have a consistent theory. For a theory to continue to grow/develop, new axioms must eventually be added. Physics is just applied math. The axioms of physics are often called the “laws of physics” are defined by nature/experiment. Logic constructs the theory just like in math. If a contradiction appears in physics, then the axioms were wrong (or the experiment that defined the axiom was poorly designed – or only an approximation as in Newton’s laws). A math theory need not be constructed with axioms that reflect nature. That doesn’t mean the math theory is wrong – just a different starting point for the application of logic.

As a mathematician said via e-mail (not approvingly), “To me that reads *exactly* like a physicist’s account of mathematics.”

Craazyboy yes there is an identity relation between M and R, in the same way pq=mv is an identity. But economists have gone further by adding causal relationship (and so behavioral/agency aspects) to develop theories. The Mon mult theory states that R causes M.

Yes, I know and that’s when things fall apart. They are trying to capture human behavior in a math model. Rots or ruck with that.

But to clarify, I’m simply stating there is one math equation that is a consequence of fractional reserve banking – so if one were trying to develop a math model, that would be an included component. Obviously there would be many more components to identify if trying to model some closer approximation to the real financial/economic system. Then, just guessing, I’d say regulation on cap ratios kicks in as a limiting factor before the money multiplier maxes out.

Glad you also mentioned pq=mv. That’s my other “core truth” in my albeit incomplete mental model I use when thinking about things economic.

I always get confused with quantity and quality… defectively speaking…

Disheveled Marsupial… file under willfully breaking da laws…

My understanding is that there is a “money multiplier,” since the same dollar bill can be spent over and over, but that this is far from the whole story (which is what most economists would have you believe). This is what the IMF found when they pointed out not too long ago that each dollar of government spending led to more than $1 of GDP growth.

Is there a money multiplier? Yes. Do loans create deposits? Yes. No contradiction here, that I can see.

Nope. If you finally get the MMT meaning of “loans create deposits”. They are telling us that if someone gets a loan it ends up deposited in some one else’s account eventually, which I don’t find to be a big step forward in explaining the expansion of credit in a fractional reserve banking system.

On the other hand, it makes for some nice click bait.

The step you’re missing, I think, is the Fed. Bank loans in-and-of themselves can’t add to the money supply, but the Fed makes sure that there are always enough reserves in the system to fund all loans – so if the amount of loans exceeds the reserves necessary to back them, the Fed increases the money supply. Loans create deposits (on the macro-scale) through the mechanism of the Fed’s interest rate-setting mechanism. That’s my understanding, anyway.

Down below I did a quicky response to fresno dan folding in the Federal Reserve role in money creation. They first made some in 1913 by buying some treasuries, and do it on a continuing basis at various levels ever since. I think the conventional terms for this money are words like liquidity, base money and “high power money”. High power money I guess gives some hint that it will have an outsized effect on the economy because it hasn’t been “expanded” or “multiplied” yet. The Fed balance sheet is presently $4.5 trillion – so that’s basically the amount of “liquid money” circulating around the economy at the “macro” velocity of transactions rate.

One nit to pick is the money multiplier could more accurately be called the “money to credit multiplier”. Credit is borrowing against the future, and liquid money is the grease that allows to credit wheels to turn. One can see the multiplying potential there, I think.

Once again, MMT confuses the issue when they state the “Fed provides reserves.” In a fractional banking system, banks are required to keep I think around 8% of checking and savings accounts in their Fed reserve account. Sure, during a financial crisis the Fed makes emergency loans, Congress makes bank bailouts, and after the banks pay salary and bonuses some of these funds appear in the bank’s required reserves fund at the fed. It’s all double entry bookkeeping, and I know Bill Mitchell likes to stress how important double entry book keeping is. So there’s that, I guess.

The reason the Fed sets interest rates is to attempt to control the level of economic activity at what they believe is an acceptable level of inflation. The idea being consumers will borrow more at low rates, corporations will invest more because their ROI calcs goes positive and visa versa. The Fed achieves the target interest rate using FOMC transactions, which is basically varying the quantity of keyboard money to buy short term treasuries – or going the tightening direction, sale of treasuries from the Fed balance sheet. Supply and demand then drives the price of money – resulting in their short term interest rate.

That’s enough typing for now. I’ll leave it up to others to contort what goes on into whatever the proper MMT verbiage is, if they feel it’s really necessary. But please don’t include financial crisis as being fundamental to MMT. Unless you are trying to say we need to go back on the gold standard and 100% reserve banking* :)

* But then no one would get loans, and I’ll never get interest on my savings accounts.

“This is what the IMF found when they pointed out not too long ago that each dollar of government spending led to more than $1 of GDP growth.”

I’ll try and touch on this one too. This is not a new discovery. I think it’s pretty well proven theory, assuming we like the details of the GDP and it got distributed more or less to our liking. A related concept here is the little folk spend all they get, which helps the economy because it passed thru more hands – and there we get back to the velocity of transactions.

Menzi Chen is the expert on this – I think it’s called the GDP multiplier, but I can’t remember for sure. There is a econ think tank that has done numerous econometric studies on this.

Deposits are included.

He is not only talking about M1. Other forms of US currency, like checking account balances, also fulfill his definition of money.

One of my favorite subjects ;-) This was a very comprehensive summary. But let me summarize the summary …

Money is a government approved liquidity instrument. From Croesus until today, the form of money has changed, but the purpose has remained the same. There are secondary aspects like … store of value or wealth dug out of the ground that enriches governments or mining companies … but as a tool to monetize anything and everything … money is unique. Could be chocolate bars or binary bits on a special spreadsheet … so the subject is confusing because it is so polymorphic. As long as the government is viable, and the liquidity vehicle is socially acceptable, it does its job. In the case of derivatives … if a derivative can’t change owners … as long as there is no secondary market … then it is insurance … but if the derivative can change hands … and there are people other than the originators/first owners who buy/sell them … then they are money.

Can you pay your taxes in derivatives? No. And are those derivatives not denominated in dollars? Yes, they are. Which means that they are not money, but a commodity.

Consider Derivatives = Bets, then derivatives nature becomes clear.

James are you saying there may be a problem with a debt currency system that has a mire few hundred trillion in derivatives floating around in our currency system. Its’ only real issue that the amount of derivatives represents several times the GDP of the world. The lord of finance the Federal Reserve is watching over us; or at least till we bankrupt our nation.

We should note the difference in money which is government back and derivatives which are asset backed; this article is only about fiat money.

“So to be redeemable a monetary instrument does NOT have to be convertible. As such the fair value of a monetary instruments, its net present value, is face value.

……

This confuses irredeemable and unconvertible. The monetary base is redeemable. This point of view also raises other problems:

Remember that balance sheets are interrelated so if a financial liability is worth zero in one balance sheet, then a financial asset must be worth zero in another balance sheet. Turner makes an accounting error.

Why would the private sector be willing to hold something that is worth zero? There is no benefit that comes from accepting a monetary instrument, not even avoiding prison because taxes cannot be paid with government monetary instruments.

If valued at zero then balance sheets should record a large loss of assets (and net worth) for banks, firms, and households: Your savings are worth nothing in nominal terms!”

============================================

I do not understand this:

“There is no benefit that comes from accepting a monetary instrument, not even avoiding prison because taxes cannot be paid with government monetary instruments.”

Uh, I don’t get it – I thought earlier the author made a big deal that monetary instruments were “redeemable” – if that doesn’t mean into some form of “money” (dollars??? currency??? or electronic signals sent to your bank account – how my pension “money” is sent to me) that is acceptable to the government for paying taxes, than I don’t understand the point of using the term “redeemable.” Is the sentence phrased as a negative argument – i.e., would it be clearer (at least to me) if it had been worded:

There is no benefit that comes from accepting a monetary instrument, not even avoiding prison because taxes cannot be paid with government monetary instruments UNLESS IT IS REDEEMABLE.

Still, very interesting and informative – I especially liked the primer on cowry shells as well as the salt cakes.

Has there been one of these articles by the author on credit? If so, if someone could provide the posting date I would very much appreciate it.

(((James Levy

May 30, 2016 at 6:23 am

I agree. If all those trillions aren’t money, what is it? And it certainly seems to show why private money creation ended in the early 1900’s and when we “deregulated the financial world, it leads to disaster, e.g., the great recession)))

I wish the author had addressed the premise that “money is debt” and that debt is necessary to “create” money. I have often heard that governments must run deficits elsewise there can be no “money.”

And of course, me being me, its funny how mortgage debt gone bad that causes losses to financiers is a horrible, no good terrible thing that must be ameliorated by “money” “created” by the FED, but somehow the mortgage debts of homeowners gone bad ABSOLUTELY, POSITIVELY CANNOT be made up for by the FED….

When I talk about the fact that there is no benefit, it is in the context of Turner’s sentence. If gov monetary instruments are not redeemable as Turner says, then they can’t be returned to the gov for any reason, not even to pay taxes.

Regarding the money and debt topic. Maybe the previous post would help (part 15). Three points

1-bank money creation involves a non-bank agent going into debt. Bank and non-bank are swapping promissory notes (check part 10 of this M&B series at New Economic Perspectives)

2-fiscal policy allows monetary creation without non-banks going into debt

3-all monetary instruments are financial instrument and as such they are the debt of their issuer.

@fresno dan – This post is the latest in a series by Eric Tymoigne that you can find at the New Economic Perspectives website run by the economics department at UMKC. I think it’s the material he uses in the classes he teaches there. I haven’t read them all, but I’m pretty sure he covers your questions.

(Eric posted while I was writing this.)

“I wish the author had addressed the premise that “money is debt” and that debt is necessary to “create” money. I have often heard that governments must run deficits elsewise there can be no “money.””

Simple enough. The Federal Reserve buys some Treasuries and money is born! Then it trickles down from there, even to corporate payroll accounts, which is the preferred way for most of us to get our hands on some of it, because then we don’t have to give it back, at least in the present system.

Then as the treasuries mature the Fed keeps buying more. They “target” a steady state quantity of “liquid” money. This is pretty close to the size of the Fed balance sheet. Currently around $4.5 trillion dollars.

You know, thinking about this a great deal, it seems to me that “borrowing” is how “money”, and value for that matter, is created.

Look at labor – work at most jobs (writers are the only people I know of you get “advances”, i.e., paid in advance for their work – are their others?) is performed prior to being paid – laborers are essentially “loaning” their labor and what they have produced to their employer (at 0% interest – the man is screwing me!!! Well, at least its not negative interest) – when your employer pays you, you are even (sure, you have worked another two weeks and are owned for that, but the two weeks prior you are even).

Now your employer has paid you a little less than the total worth of what you have produced (don’t worry – I’m not going Marxist) – my point is that your labor has increased the sum total value of society. After the laborers’ effort, and his pay, there is net more in the world than prior (more stuff, more restaurant meals, more medical care, etc.) – no “money” is destroyed in this scenario.

(sure, some people are diminishing value ((soldiers)), but on the whole we are getting more “value” from people working).

Interestingly, if laborers were paid prior to their work, I imagine it would not actually make that big a difference – – – sure, a few people would try and collect pay and than disappear, and employees would be vetted even more rigorously than presently, but on the whole it would be pretty much the same.

So banks creating money, or the government creating money “out of nothing” or more accurately, LOANING IT INTO EXISTENCE, something quite disturbing to me in my youth, I have come to see as necessary and benign. I suspect some of the complexity of what is going on is a big McGuffin designed to confuse, misdirect, and obfuscate the grift going on at large financial institutions. When Bank of America receives a ruling that exonerates Countrywide from fraud, we have divorced consequences from actions. Making loans that GET PAID BACK is a job – and if you can’t do a job you should be fired. And just like a cashier that takes money from their employer’s till, bankers that make loans that they know can’t be paid back are crooks.

And it seems to me that the way things are being run is all to the advantage of the 1% and higher, and to the disadvantage of everyone else…

There are PLENTY of bankers in this country – we could have fired the management of any bank that REQUIRED a government bailout, and I suspect we would be far better shape today.

“Clearly, a gold ingot is not a monetary instrument.”

That’s why you don’t find any of the barbarous relic in Fort Knox or in the sub-basement of 33 Liberty Street.

Oh, wait … !

Take a look at the Federal Reserve’s assets in their H.4.1 report. About 20 lines down from the top appears “Gold stock” at $11.041 billion.

It’s carried on the books at an anachronistic price of $42 an ounce. Valued at the current gold price, it’s worth about $315 billion.

Just a commodity spec, comrades. JYel could just as well be stockpiling sugar, pork bellies and soybean oil on the lower floors of the Eccles Building.

You see central banks doing this all the time. Sometimes hungry staffers break into the pork belly locker on nights and weekends, hollering “Bacon! Bacon! Bacon!” /sarc

Are you being purposefully obtuse? Sometimes I can’t tell if you’re trolling, or just very confused.

Not all assets are “money,” you know that right? In fact, that’s why assets (apart from money) are priced in terms of money. Do you seriously think that anything with value is a form of money?

The Fed stockpiles gold because it’s convenient, not because it’s money. Pork bellies rot, gold bars don’t.

The fact that the gold is just lying there, and has a price expressed in dollars – and an ‘anachronic’ one at that – should make clear to you it’s not ‘money’. Maybe it ‘should be’ money in the world you dream of, but in this one, it’s not money.

What about the monetization of data?

http://dupress.com/articles/data-as-the-new-currency/

As a new form of currency, data offers the promise of new wealth for the private and public sectors alike.

How does Big Data hold up in this analysis–esp. when the data’s value are evanescent and riddled with errors? Is this just magical thinking of Big Data evangelists?

To answer the question “is this money?” just ask yourself if it can be used to settle your tax bill. If not, the answer is no.