By C.P. Chandrasekhar, Professor of Economics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Jayati Ghosh, Professor of Economics and Chairperson at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Cross posted from the Business Line

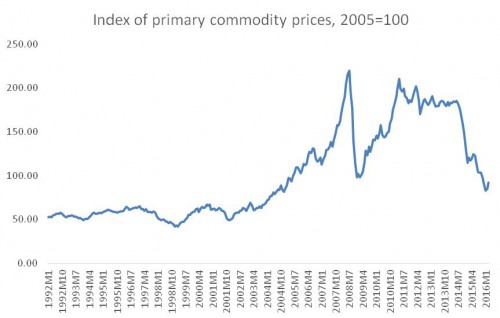

There was a period in the 2000s when primary commodity prices appeared to have bucked their long term trend of stagnation or decline. As Chart 1 shows, between the trough of December 2001 and the peak of August 2008, the price index for all primary commodities (in US dollar terms) rose by 445 per cent, that is nearly four and a half times.

Chart 1

This increase came after a decade of relative stagnation in nominal dollar prices (which reflected a decrease in relative prices of commodities) over the previous decade. The strength and rapidity of the increase in prices over the 2000s led some analysts to argue that changing patterns of global production and consumption meant that there would be secular tendencies towards increase in such prices in the medium term. In particular, the more rapid growth of and therefore increased demand from China, India and other “emerging markets” was seen to indicate a structural shift in global demand that would generate continued increases in primary commodities prices for some time.

However, this was at best a partial – and at worst a misleading – argument. As it happens, much of the increase in prices (and their velocity) was due to speculative activity in such markets, aided by the financialisation of commodities as the involvement of non-commercial players in the commodity futures markets was both enabled and grew more significant. This became starkly evident with the subsequent collapse of such prices in the second half of 2008. The revival of such prices from early 2009 once again did not reflect “real” economic forces so much as the impact of loose monetary policies in the North after the Global Financial Crisis. Almost unlimited access to funds combined with near zero interest rates and continued inadequate regulation to make investment in commodity futures relatively attractive for financial players. So in the following years, the IMF’s primary commodity price index rose almost to its previous peak and stayed high even without any significant revival in global real demand and with faster expansion in supply relative to demand.

But that phase too has been over for around two years now, as the index has fallen sharply once again, and in the first quarter of 2016 the index was around 55 per cent lower (or less than half) of the level achieved in mid-2014.

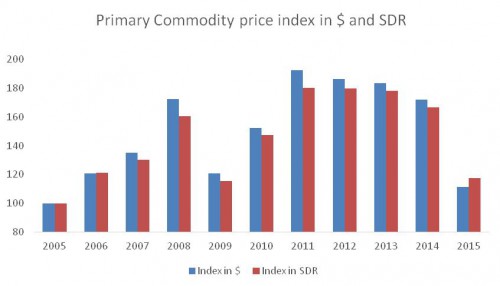

Since this index is calculated in terms of nominal US dollars, it would obviously be affected by exchange rates, and it is true that the US dollar did indeed fluctuate quite a bit over this period. Chart 2 describes the change in the index in both dollar and SDR terms, and it is immediately evident that the variations in SDR terms were generally not as sharp. In general, periods when the US dollar is stronger tend to be those of lower commodity prices, reflecting the dollar’s significance as the underlying numeraire for currencies across the world. However, even in SDR terms the recent decline in the price index has been steep.

Chart 2

It now seems – and indeed this is confirmed by projections from almost all the major international organisations – that this particular “commodity “supercycle” is now in the phase of downswing and primary commodities will stay low for the next few years. Since finance no longer finds this an attractive outlet, this will further add to downward pressure on prices.

What does all this mean for the developing countries whose economic fate still seems to be tied closely to the movement of primary commodity prices? To assess this it is necessary to disaggregate the price behaviour of different categories of commodities, since this will affect importers and exporters differently.

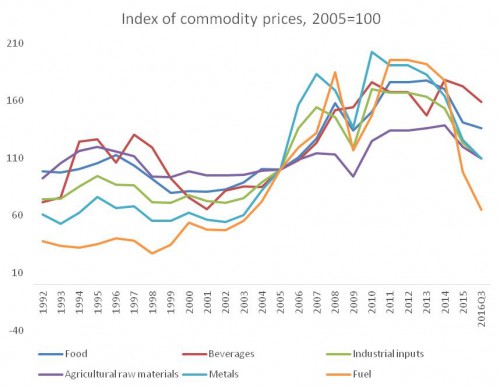

Chart 3

Chart 3, which provides such a disaggregated look, shows that the most volatile prices have been those of food and fuel. In the most recent phase, the sharpest decline has been in fuel prices, and particularly in oil prices, which is clearly bad news for oil exporters and good news for oil importers like India. However, even for the latter, the news is not uniformly good, since the declines in exports and therefore incomes of oil exporters have meant declining import demand from them as well, which in turn has affected the export demand for many oil-importing developing countries.

Similarly, food prices have come down sharply from their peak, which affects food exporting countries and also indirectly feeds into domestic food inflation in most countries. However, while global price increases show high pass-through to domestic prices, declines in global prices do not always translate into declines in domestic food prices. In many developing countries (including India) food prices remain high and even increasing in a wider context of deflation. So farmers may be losing out from the global price shift, but consumers are still paying relatively high prices for food.

The other interesting point that emerges from Chart 3 is that some commodity groups, particularly agricultural raw materials, have shown very little change over this entire period. So commodities like cotton and jute did not really experience significant price hikes, which means that they have also not declined as much – in fact, their prices have fluctuated around a stable trend. So farmers producing non-food cash crops did not get to cash in on the boom but they still now face the effects of what is generally acknowledged to be a slump.

The price trends described above show how financialisation of commodities has served to amplify and exaggerate instabilities and fluctuations, in ways that do not benefit either direct producers or consumers.

‘It now seems – and indeed this is confirmed by projections from almost all the major international organisations – that this particular “commodity “supercycle” is now in the phase of downswing and primary commodities will stay low for the next few years.’

It’s the ‘confirmed by major international organisations’ — a phrase which I’d be unable to deliver without bursting into laughter — that means it’s almost surely wrong.

After this morning’s mediocre U.S. jobs report, it appears that a June rate hike is off the table. The old yellow dog, gold, is woofing in delight, up almost 1 percent.

Slow growth and easy money are like fertilizer for the golden beanstalk.

Wild card in the mix is Trump, who with his usual big mouth was talking up low interest rates and a weak dollar yesterday. If Trump looks like a serious contender, the dollar is going to suffer and commodities are going to crank higher, monster style.

Let’s all sing together now:

The problem for all prognosticators is that the trend can be so easily and profoundly effected by hot money pouring this way or that. The Investor Class has sucked up all the liquidity, and they are capable of blowing bubbles or inducing contractions within very short time horizons as they stampede in and out of one asset, nation, or another. And sucking the hot money back out of the system is now nearly impossible, for it would involve both shuttering the tax havens and introducing wealth taxes; good luck accomplishing either of those things, even if by a miracle Sanders were to be elected president.

The excessive liquidity will only be dried up by a massive crash with no bail-outs. The results of that, however, will be the immiseration of billions and perhaps the deaths of millions. Nice choices they’ve left us.

While it is true that printing massive amounts of US dollars normally drive up commodity prices, these are special circumstances. We’ve had easy money for 25 years. It’s the law of diminishing returns: at this point, more easy money is not going to drive up oil prices the way it has since the turn of the century. The laws of supply and demand still apply, and we have a supply glut as well as weakening demand (a stagnating global economy). Oil prices will remain low for years, and any time they rise about $60-70 a barrel, oil and gas firms will start drilling shale like crazy and then prices will go back down. We won’t see $100 unless there’s a huge bout of inflation. The inflationistas have been predicting this for years but free trade and foreign competition keeps the prices of consumer goods down. While I do believe that at some point, we’ll get hyperinflation and it’ll destroy the economy, but that could be decades away (and it will occur after a lot of other nasty crises).

I think it’s a double whammy, we have to suffer the rampant ebbs and flows of government subsidized speculation in all of the stuff we need: oil, food, steel, cotton (and in a second-order effect, even water and air). But they have also completely financialized money itself. Since the US defaulted in 1971 (when Nixon closed the gold window), our only choice is to be jerked like marionettes on a string by the passing whims of Ph.Ds in the Marriner Eccles Building, and math geeks in hedge fund offices in Greenwich, CT.

Just one of those string-jerkers would be bad enough, taking it from both ends is a a sick joke on all of us. So we all become just Kremlinologists, trying to sniff out what these priests will do next, and then trying to front run them. Vancouver real estate, anyone? Wait, you mean someone actually lives there, and needs to make a mortgage payment or pay rent? And somebody somewhere actually needs to feed their family tonight? Out of the way, losers, I want another billion in my offshore account…

Reminds me of these words from a previous “brain trust”―“We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you’re studying that reality — judiciously, as you will — we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.”

After a year of reading your posts, I would love to sit down and have a beer with you. You have a visceral wit.

Thanks. I share the sentiment.

Good backgrounders:

http://commodities.about.com/od/researchcommodities/a/How-The-Dollar-Impacts-Commodity-Prices.htm

http://www.salientpartners.com/epsilon-theory/optical-illusion-optical-truth/

Food prices have come down? Please tell me WHERE? In what area of the world have food prices lowered? I would like to know.

It might involve the Substitution Effect.

Replacing organic stuff with toxic ones helps to tame inflation.

Yeah, I just spent $10 on enough Granny Smith organic apples for Mother’s Day apple pie. Incredible that 6 apples can cost almost as much as most people earn in an hour.

Well said Warrior.

This article contains a lesson I have been taught before. As a student of economic history it has commonly been the case to my knowledge that although all sorts of plausible reasons are adduced at the time of a problem, the real and ultimate cause is usually speculation.

My first example is the commercial failures of 1793 which were attributed to the rise of democracy in France until investigation revealed it was due to City speculation. All the subsequent examples are the same.

In this case, Professor Chandrasekhar identifies speculative activity behind the astonishing rise in commodity prices since 2000. It seems we always shoot ourselves in the foot.

Is it really not possible to control speculation or at least direct it into really speculative areas and away from necessaries like food, clothing and housing?

The problem is we encourage the leveraged speculation with the tax code. We don’t use the income tax code to cool down the markets. We use monetary policy, which reduces comsumption demand which can bankrupt producers.

I believe in economics there is almost always a cause and effect.

The tax code has the power to guide people’s financial decisions. This can be verified by examining how people’s financial decisions change when Congress changes tax policy. Congress and economist recognize this principle. This is why they have changed tax policy during many President’s term in office. Tax policy changes can help shorten a recession. Government automatic stabilizers (unemployment insurance, food stamps, Medicaid) can help a recession from going deeper.

I believe we need automatic stabilizers to tone down booms before they burst. I believe automatic tax policy changes should be used, before monetary policy is used, to cool down an economy before it goes bust to help maintain employment.

The automatic economic stabilizer I am referring to is the 2% Appreciation/Inflation Taxation Policy. This tax policy will not increase overall taxes. Its purpose is to help prevent bubbles and financial crisis.

The seeds, of the Great Depression , were planted by Congress in 1921 when it lowered the capital gains tax rate from 73% to 12.5% and the top tax rate to 25%, when Republican Warren F. Harding was elected president. The tax rates were left at those rates until all the excessive credit that was created came tumbling down, creating a world wide financial crisis.

The seeds, of the Great Recession were planted when Congress, and President Reagan, President Clinton, and the two Bush Presidents lowered the capital gains tax, in steps, down to 15%, a 0% capital gains tax was enacted on the sale of primary homes, and the top tax rate was lowered to 35%. And Congress excessively financialized our economy by deregulating Wall St., and the banking system during President Clinton’s presidency. The tax rates were left at these rates until all the excessive credit that was created came tumbling down in 2007/2008 creating a world wide financial crisis!!

http://www.taxpolicyusa.wordpress.com http://wp.me/p42WQA-7c

Why the dramatic rise in commodity prices? The hedgies went long. And deep. Into every commodity crevice they could find. My neighbor sat in one of the pits at the Board of Trade in Chicago during the days when

floor traders knew where the orders were coming from. He watched the money pour in and when the prices were high enough, he saw the money pour out. This has happened to every single thing that humans can put a price to: everything has been ruined financially for profit. Now what? What can they possibly ruin next? The only thing left is to go back to square one and start inflating everything all over again.

Tough to make a speculative fortune/hit a five bagger in a flat market. It’s even better if any volatility is to some degree within your control loop. You need volatility, information and suckers–or maybe just any two of those. The agricultural raw materials markets seem gaming resistant.

Is increasing financialization of commodity (and currency and seemingly all other) markets making imposition of financial transactions taxes any more likely? After articles like this, such a tax looks more and more like a carbon tax — an attempt to internalize externalities.

Sorry to be late to this article, but I completely disagree that cotton was not affected. There was a huge spike in cotton prices. I am in an industry where cotton fabric sales is a major component. The wholesale prices climbed from an average of $4/yd to $6/yd in a year. This lead to a very large drop in consumer spending. Going from $8/yd to $12/yd was too much of a jump for our consumers. Of course when cotton prices went back down, the wholesale price stayed at the high number. Nothing has been the same since.