Yves here. Even though this post describes why Australia is particularly vulnerable to an external shock like Brexit, it contains broader lessons. One might be an economic analogue to the observation in Anna Karenina: “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The fault lines in economies are often specific, due to differences in their real economies, structure of financial systems, financial regulations, and legal regimes, and behavior of their political classes.

In Australia, the housing bubble was particularly risky because Australian banks relied heavily on foreign financing. The authorities got religion for a few years after the crisis, but allowed the Big Four to go back to their old ways.

What this article also highlights is how many countries are vulnerable to sudden falls in international capital flows. That was a compliant of the BRICS and other countries when the Fed’s ZIPR and QE were driving hot money into their economies. They knew the good times would be short-lived and the hangover would be painful when the speculative capital exited.

And what the article alludes to at the end is that Brexit, or upcoming elections, or both, could produce not just destabilizing cyclical shifts or sharp falls in international money flows, but that we may soon see a major secular change. Your humble blogger has warned for years (most explicitly in ECONNED), that paradigm breakdown was the most likely result of the financial crisis. High levels of international capital flows lead to ever more frequent and severe financial crises. Yet politicians would find it too unappetizing to make deep enough reforms (which would among other thing necessitate shrining the amount of private credit and with it, the size of the financial system). The most likely result was patching up the system until it fails irreparably.

By David Llewellyn-Smith, founding publisher and former editor-in-chief of The Diplomat magazine, now the Asia Pacific’s leading geo-politics website. Originally posted at MacroBusiness

According to Wikipaedia “chaos theory is a branch of mathematics that deals with complex systems whose behaviour is highly sensitive to slight changes in conditions, so that small alterations can give rise to strikingly great consequences”.

Australia exists in a state of blissful ignorance of this theory. How else to explain an economic model that relies upon the smooth running of just about every other economy on earth? Let me explain.

Back in 2009 when I co-wrote The Great Crash of 2008 with Professor Ross Garnaut, the book proved to be very influential in policy circles owing to one central observation. The book described the process through which the Australian economy had been transformed in the late nineties and millennium to a model highly vulnerable to external disruption:

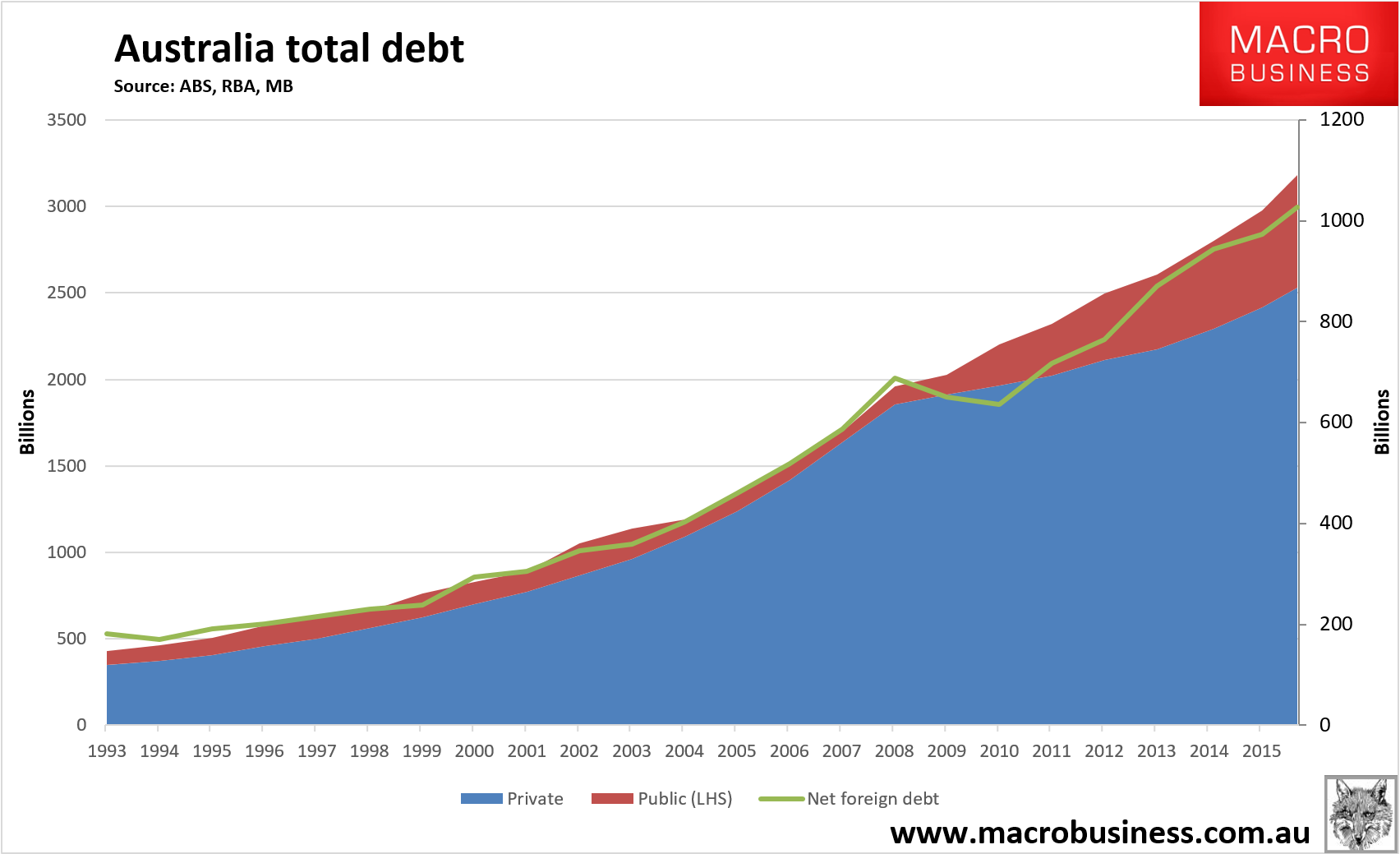

The growing asset boom and falling savings rates meant that ANZ, NAB, CBA and Westpac found that the demand for loans outstripped deposits. Australian banks’ ratio of deposits to total liabilities was 59 per cent in December 1994. By 2000 the ratio had dropped to 46 per cent. It finally hit 43 per cent in late 2007.30 Competition for loans with the new shadow bank sector was also intense, which gave rise to the big four’s own shadow banking activities. They were cautious about securitisation, but their high (AA) ratings provided them with a different method for accessing funds to lend: the issue of bonds directly to international investors.

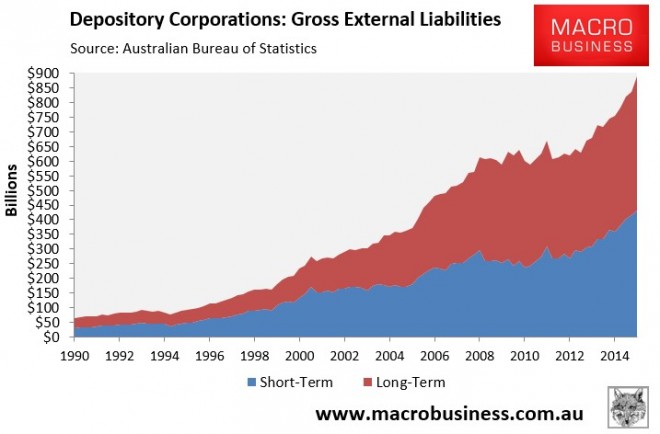

The banks’ foreign wholesale borrowings grew from A$30 billion in 1990 to A$100 billion in 2000. From there the borrowing escalated, reaching A$357 billion in 2008.31 The Australian housing and consumption boom of the early twenty-first century was funded by foreign borrowing by the banks on a scale far greater than had ever happened before.

Traditionally, banks had been cautious about this method of raising funds because it carried the added risks of managing currency and foreign interest-rate fluctuations. Consequently, according to Philip Bayley, former director of Capital Markets at Standard & Poor’s Australia, ‘there was a direct correlation between the big four’s steady mastery of currency and interest rate swap derivatives and the rise of their borrowing in international wholesale markets’. These shadow instruments grew even more rapidly than the underlying borrowing. In 1990, Australian bank books showed a combined total of A$1.57 trillion notional derivative exposure. By 2000, the notional figure had grown to A$3.59 trillion, and in 2007 shot above A$13 trillion

The policy fallout from the GFC and the book was an acknowledgement that Australia had, in effect, developed a fragile economic model, one overly exposed to the flapping of far flung butterfly wings. There were three policy implications to this, all of them openly acknowledged by Australia’s key economic managers at the time:

- Treasury recognised that in a world where major offshore financial centers could close overnight then its doctrine of allowing foreign borrowing to run riot because it was derived from the decisions of “mature adults”, creating huge current account deficits in the process, was high risk and required serious mitigation. What followed was the largest fiscal consolidation since WWII;

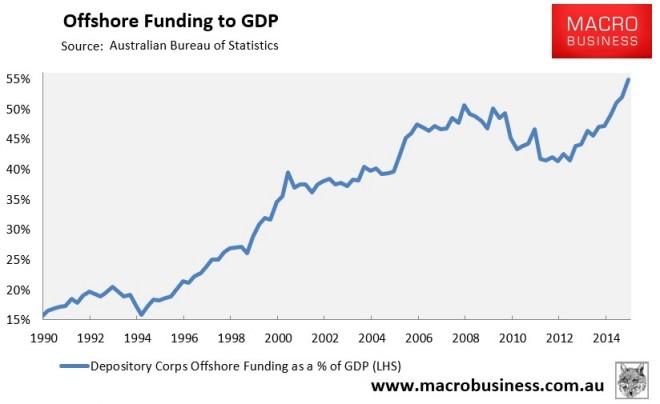

- the Reserve Bank of Australia deliberately raised interest rates to difficult levels for Australia’s east coast mortgage economies in 2010 driving historic levels of deposit growth and flat-lining offshore borrowing;

- the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) pursued a policy of dollar-for-dollar deposit-in, loan-out for banks, ensuring deposit competition and a push outwards in the maturity profiles of offshore borrowing.

All of this was enabled by the serendipity of the commodities boom and was handled well if not as aggressively as it needed to be. The result was an historic four year buffering of Australia’s fragile economic model as offshore borrowing stalled and its ratios to growth fell, what MB described at the time as the Great Disleveraging from 2008-2012:

However, what appeared to be a structural change in thinking proved ephemeral. The same commodities boom that had allowed the lessons to be learned with little pain, in time fed into the old way of thinking, that Australia was exceptional, that its adults were somehow more wise and all-seeing than those of other countries and, as the commodities boom ended so did the repair work on Australia’s fragile economic model.

Indeed, one could be forgiven since for concluding that no lesson was learned at all as offshore borrowing screamed higher after 2011, its maturity profile radically shortened and fragility poured back into the economy, made all the worse by a dramatic deterioration in public finances, funded again from offshore:

In the past two years we’ve seen two more countervailing policy waves by folks in the system that still grasp this fragility. The first was the Murray Financial System Inquiry which ruled in favour of higher capital for banks and lower leverage ratios for mortgages in particular. It was incremental rather than step change but defined the “fragility” problem very clearly. Alas it was too late and not radical enough to prevent the post 2011 borrowing binge, nor could it prevent the public debt splurge now underway.

The next wave of policy innovation came with APRA finally moving to dampen the borrowing binge via macroprudential policies, something that the Murray Inquiry had unfortunately failed to endorse. We are seeing the excellent results of that today with mortgage growth rates tumbling as lending standards trending higher despite rate cuts and offshore borrowing slow sharply. However, there is more work to be done to prevent this debt from taking off again and, in reality, if it is pursued with appropriate vigour will probably prove to be pro-cyclical because it came too late.

It is at this last point that come back to today. Since the GFC, good people have done good things to stabilise the fragility built into the Australian economic but the structure of the system has still pushed it towards greater risk. Australia is only marginally less exposed to external disruption today compared with 2007. Non banks have been washed out and major banks are better capitalised, as well as having 60% deposit funding funding versus 50% back then but any serious freeze in global finance will still render the major banks insolvent in a ridiculously short period given they will be unable to roll over their liabilities. They’ll be able to lean on the RBA for nearly free liquidity but even so credit ratings agencies explicitly build in a two notch upgrade to bank ratings based upon an implicit public guarantee of the bank’s liabilities and as the Budget deteriorates so too does that guarantee.

So, we haven’t entirely wasted the previous cycle in terms of an anti-fragility policy agenda but we’ve done an awful lot less that we should have. And we are about to discover the efficacy of those efforts as first Brexit then a whole series of butterflies flap their wings across the globe. Anatole Kaletsky sums it up pretty well at Project Syndicate:

The febrile behavior of financial markets ahead of the United Kingdom’s referendum on June 23 on whether to remain in the European Union shows that the outcome will influence economic and political conditions around the world far more profoundly than Britain’s roughly 2.4% share of global GDP might suggest. There are three reasons for this outsize impact.

First, the “Brexit” referendum is part of a global phenomenon: populist revolts against established political parties, predominantly by older, poorer, or less-educated voters angry enough to tear down existing institutions and defy “establishment” politicians and economic experts. Indeed, the demographic profile of potential Brexit voters is strikingly similar to that of American supporters of Donald Trump and French adherents of the National Front.

Opinion polls indicate that British voters back the “Leave”campaign by a wide margin, 65% to 35%, if they did not complete high school, are over 60, or have “D, E” blue-collar occupations. By contrast, university graduates, voters under 40, and members of the “A, B” professional classes plan to vote “Remain” by similar margins of 60% to 40% and higher.

In Britain, the United States, and Germany, the populist rebellions are not only fueled by similar perceived grievances and nationalist sentiments, but also are occurring in similar economic conditions. All three countries have returned to more or less full employment, with unemployment rates of around 5%. But many of the jobs created pay low wages, and immigrants have recently displaced bankers as scapegoats for all social ills.

The degree of mistrust of business leaders, mainstream politicians, and expert economists is evident in the extent to which voters are ignoring their warnings not to endanger the gradual restoration of prosperity by upending the status quo. In Britain, after three months of debate about Brexit, only 37% of voters agree that Britain would be worse off economically if it left the EU – down from 38% a year ago.

In other words, all the voluminous reports – by the International Monetary Fund, the OECD, the World Bank, and the British government and the Bank of England – unanimously warning of significant losses from Brexit have been disregarded. Rather than trying to rebut the experts’ warnings with detailed analyses, Boris Johnson, the leader of the Leave campaign, has responded with bluster and rhetoric identical to Trump’s anti-politics: “Who is remotely apprehensive about leaving? Oh believe me, it will be fine.” In other words, the so-called experts were wrong in the past, and they are wrong now.

This kind of frontal attack on political elites has been surprisingly successful in Britain, judging by the latest Brexit polling. But only after the votes are counted will we know whether opinions expressed to pollsters predicted actual voting behavior.

This is the second reason why the Brexit result will echo around the world. The referendum will be the first big test of whether it is the experts and markets, or the opinion polls, that have been closer to the truth about the strength of the populist upsurge.

For now, political pundits and financial markets on both sides of the Atlantic assume, perhaps complacently, that what angry voters tell pollsters does not reflect how they will actually vote. Analysts and investors have consistently assigned low odds to insurgent victories: in late May, betting markets and computerized models put the probabilities of Trump’s election and of Brexit at only around 25%, despite the fact that opinion polls showed almost 50% support for both.

If Brexit wins on June 23, the low odds accorded by experts and financial markets to successful populist revolts in America and Europe will immediately look suspect, while the higher probabilities suggested by opinion polls will gain greater credibility. This is not because US voters will be influenced by Britain; of course they will not be. But, in addition to all the economic, demographic, and social similarities, opinion polling in the US and Britain now face very similar challenges and uncertainties, owing to the breakdown of traditional political allegiances and dominant two-party systems.

Statistical theory even allows us to quantify how expectations about the US presidential election should shift if Brexit wins in Britain. Suppose, for the sake of simplicity, that we start by giving equal credibility to opinion polls showing Brexit and Trump with almost 50% support and expert opinions, which gave them only a 25% chance. Now suppose that Brexit wins. A statistical formula called Bayes’ theorem then shows that belief in opinion polls would increase from 50% to 67%, while the credibility of expert opinion would fall from 50% to 33%.

This leads to the third, and most worrying, implication of the British vote. If Brexit wins in a country as stable and politically phlegmatic as Britain, financial markets and businesses around the world will be shaken out of their complacency about populist insurgencies in the rest of Europe and the US. These heightened market concerns will, in turn, change economic reality. As in 2008, financial markets will amplify economic anxiety, breeding more anti-establishment anger and fueling still-higher expectations of political revolt.

The threat of such contagion means a Brexit vote could be the catalyst for another global crisis. This time, however, the workers who lose their jobs, the pensioners who lose their savings, and the homeowners who are trapped in negative equity will not be able to blame “the bankers.” Those who vote for populist upheavals will have no one but themselves to blame when their revolutions go wrong.

Quite right, except for the last paragraph. We are only here because people blame the bankers and their policy buddies and even an elective unraveling of the system will make that worse not better. After all, the globalists built the system that folks want out of. If anything Kaletsky is, I think, underestimating the psychological shift against globalisation underway and there are a series of lightening rods ahead:

- taken at face value, a Trump Administration will be anti-China, pro-protection and nationalist with all kinds of economic struggle likely to turn hot across the Pacific;

- Fraxit looms as a real possibility in 2017 as National Front leads national polling which is the end of the euro as we know it;

- China’s debt mountain appears manageable until the Sixth Plenary of the Chinese Communist Party in mid-2017. After that, the reformist Xi Jinping should have complete control of the Politburo and be able to renew his economic transformation to much slower growth.

Chaos is coming in one form or many and Australia is not ready for it.

Australia is often called ‘the Lucky Country’, but one wonders if over the longer term, regression to the mean means that when things eventually goes wrong, it will really get nasty. Its struck me as an outsider that Australia is very dependent on imports for a wide range of basic products, which implies that if there is a serious crash, a collapsed dollar could make things very difficult indeed and put a lot of people on the breadline. A very weak AUSdollar might boost tourism and exports of wine, but its difficult that this would be enough to spark a recovery. I could well see the country get caught in the sort of trap that Argentina regularly finds itself. It would well become the first high income country to slip back and get caught in the middle income trap.

The Australian dollar was very weak when I arrived (2002) at A$1 = US$0.53, but oil prices were very low then too (although with energy taxes, I found my utility charges to be higher than I had expected). The economy was doing much better that most other places that were hit with the dot-bomb actual or near recession. But consumers are now much more debt-burdened, so a slowdown (or increase in costs) will probably have a much impact than then.

I live in Melbourne. Even though I’m sure every person thinks their’s is the most uniquely screwed up country on earth, I truly believe Australia wins the cake. You won’t encounter a more smugly arrogant yet mediocre and morally decrepit and greedy and wilfully bumpkin political class and media class and middle class (not working class, American readers) anywhere than in Australia.

Britain has its English superiority, America its Manifest Destiny.

Australia’s equivalent is the Everlasting Gobstopper of Economic Boom.

No-one remembers what a capitalist cycle is. No-one remembers what a recession is, and if they do, it’s something that happens to those disgusting foreigners, the countries that are too stupid to know that if they’d just invented a never-ending housing bubble, they could feast every day anew on the eternal riches, like Thor’s goats.

Our political class, from every major party, minor party and independent politicians are fully committed to ramping up the speculative housing bubble. They are all completely embedded. Apart from their quid pro quo class ties to the banks, corporations, developers and construction companies that have an interest in inflating the housing bubble, something like 96% of our politicians from both houses of parliament personally own investment properties. There’s one senator that owns 50+ houses.

Every day for years now, I feel like I’m the protagonist in the end scene of Invasion of the Body Snatchers yelling “You fools, you’re in danger! Can’t you see?”

I’m 26, and apart from my bohemian groups of friends, most young people have become socialised and conditioned to believe wealth will arrive from their getting into the investment housing game as young as they can. It’s extraordinarily eerie. Of course the only one’s actually doing it are the middle class. Everyone else just sits by on decreasing wages as the physical geography of all our towns and cities are turned into endless strip malls of stores selling display kitchens and bathrooms and furniture.

It can’t be long now, it’s been my whole lifetime and even I’m starting to live my daily life as if this neoliberal toytown country is never going to fold.

As Doc says, ‘when this baby hits 88, you’re going to see some serious shit’

I live in Adelaide and have been here for the past six years. I know EXACTLY what you mean! I feel like Cassandra trying to warn people of terrible things to come but being completely ignored. Because they dodged the worst of the Recession, Australians seem to think they are untouchables and that the housing market will continue to go up and up. What is most amazing to me is that they are on the hook for all the money if a house they bought for $800,000 ends up being worth $350,000. There is no walking away from that obligation through bankruptcy like there is in the States. What gets me most is the amount of negative gearing that goes on.

Yep, it’s going to be insane. I think there will be one of two outcomes when the markets begins to slide, then erupts into crash.

(1) It could be like when the Black Death hit Europe in the mid 1300s. Completely rocks the ideological basis of daily life and changes everything. Gone will be all duties, responsibilities, contracts, customs, and etiquette. People will go all Dionysian in the woods. Every aspect of Australian society will become gutted out and dysfunctional, so many people will go nomad. Prelude to Mad Max. Throw in another fifty years of climate change.

(2) Nothing will change. And this will be the hugely funny outcome. Your $800,000 mortgage is now only worth half that. You still owe the bank half a million dollars. How will you pay for that? By taking on more debt, of course. Let’s go investment property shopping! The bubble will quietly try to re-inflate itself like an old whoopee cushion trying to get one last accolade.

I doubt this scenario would happen, but there would be elements of it. There is going to be so much hot air from the chattering classes that the crash was a mistake, it shouldn’t have happened, it had no right to happen, and we ought to advocate policies that will boost the average suburban house back up to the $1,000,000 mark where it belongs.

Thank you for bringing Chaos Theory into the economic discussion. Application of this theory will cause major changes to economic models (-:

As in: make all current models invalid (Chaos cannot be modeled).

There is no complete set of variables, and there is no description of the coupling and feedback among the variables, and finally (always the killer point), if there were a list of variable and their interactions, how would one test the model?

For example: Trump is a chaotic factor.

It’s not complicated, it’s the debt inflated asset bubble.

1929 – US (margin lending into US stocks)

1989 – Japan, UK (real estate)

1999 – US (margin lending into US stocks)

2008 – US (real estate bubble leveraged up with derivatives for global contagion)

2010 – Ireland (real estate)

2012 – Spain (real estate)

Coming soon – Australia, Canada (real estate).

The bankers make their excuses and learn nothing.

Since 1929 each event has been bailed out ensuring they learn nothing from their mistakes.

The bankers lending into the Australian and Canadian housing markets have no idea what they are doing.

The Central Bankers in Australia and Canada have no idea what is going on.

The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) has no idea what is going on as one of their directors is the head of the Canadian Central bank.

Neoclassical economics is blind to the debt inflated asset bubble, rendering all Australian and Canadian main stream economists blind to the problem.

2008 – “How did that happen?”

No need to adjust neoclassical economic theory because it was a one off black swan event.

But it wasn’t, see list above.

2008 stats.

James Rickards in Currency Wars gives some figures for the loss magnification of complex financial instruments/derivatives in 2008.

Losses from sub-prime – less than $300 billion

With derivative amplification – over $6 trillion

“It’s nearly $14 trillion pyramid of super leveraged toxic assets was built on the back of $1.4 trillion of US sub-prime loans, and dispersed throughout the world” “All the Presidents Bankers”, Nomi Prins.

This is just one trail of destruction, re-reading Nomi Prins’s “All the Presidents Bankers” we see another trail of destruction emanating from Wall Street.

Excessive loans into Africa and South America, destroying nations with austerity, privatising previously public companies and reducing public spending so the bankers can get their money back.

The S&L crisis where Wall Street was already packaging up toxic assets and selling them onto S&L companies to blow up later.

Excessive loans into Russia and Asia, destroying nations with austerity, privatising previously public companies and reducing public spending so the bankers can get their money back.

Long Term Capital Management blew up and posed a systemic threat to the system through the use of highly leveraged complex derivatives.

The dot.com boom (as above).

2008 (as above, they cut their teeth with toxic assets during the S&L Crisis)

Excessive loans into Europe, destroying nations with austerity, privatising previously public companies and reducing public spending so the bankers can get their money back (European banks were the main culprits here).

The psychopath never takes responsibility for anything.

The psychopath never learns from mistakes.

The psychopath is very good at explaining away mistakes and blaming them on someone else.

The psychopath is given away by the trail of destruction that they leave behind.

Draw your own conclusions.

There was not that much margin lending in the 1999 bubble. It was high relative to recent levels, but not in absolute terms. That’s why the US had only a pretty mild downturn as a result despite the magnitude of the bubble This was mainly a mania, like the tulip bulb craze.

That’s what I had thought until I saw a graph like this:

https://www.theinvestorspodcast.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/NYSE-margin-debt-SPX-since-1995.gif

How did the efficient market hypothesis survive the dot.com boom and bust?

Another neoclassical economic mystery.

1. That proves my point. Even at its peak, margin debt was not consequential from a macroeconomic perspective. And since it is 1. Limited to 50% of of the value of a stock and 2. Margin is marked daily, the losses on margin debt are not going to be significant from a creditor standpoint. It’s also not a significant driver in absolute terms. $600 billion of margin lending to a total market cap of $15.1 trillion in 2000 is not significant, versus an estimated 70% to 90% of the Roaring Twenties bubble at its peak. In fact, the causality likely ran the other way: the bubble mania led more people to try to get more exposure via margin borrowing, as opposed to margin borrowing driving the price appreciation.

When bubbles become dangerous to an economy is when they are fueled by debt and their collapse damages the banking system. Margin lending against stocks in the US is now set up so that can’t happen.

I did do a bit more reading later and the dot.com bust led to massive losses but, as you say, it didn’t feed back into the banking system and it is the money destruction on bank balance sheets that really does the damage.

It is strange the safe guards still remain in the stock market where they have been removed everywhere else.

I think the runup was so fast that even though a lot of people spent more based on their (temporarily) higher net worths, they didn’t go and really ratchet up unless they were the few who’d cashed out to some degree.

Living in Sydney and loving it.

Great discussion of the banks’ external funding and related vulnerabilities. You can’t overestimate how much support the Big Four banks get from the government, from the deposit guarantee, to a free pass for things like LIBOR fraud, to huge shareholdings by the so-called “Future Fund”.

But the “globally connected” argument cuts both ways, the Australian property market (farmland, residential, commercial) is no longer some kind of isolated economic case that must be solely supported by local income and is threatened by local indebtedness. Quite the contrary, Australian property is now part of the juggernaut of regional wealth extending to Singapore, HK, and Beijing. Buyers from those locales get off the plane here, see air they can breathe, food they can eat, water they can drink, a place for their kids to learn English at university, and a government that can be trusted. The absolute tsunami of wealth leaving China finds a happy home here.

So yes banks are critically exposed to overseas funding, but there are many other sources of capital available to keep the bubble from popping for a long time to come. As the PM says “Australia is a lifestyle superpower” and yes, I think he’s right.

Right on!

Oz is a continent. It has billions of tons of Titanium, zircons and millions of tons of Thorium. It has a series of mountain ranges that are 66% magnetite. Despicable coal is still being discovered and has reserves of hundreds of years. We ban exploration in National Parks and the Barrier Reef, even though it is known to have oil. It is the sunniest country in the world per capita. I could go on! The poorest reserves are in the platinum group of metals….. If the world goes back to metal coin, we are fabulously rich!

We are doubling population every 25+ years. It selects mostly well off older, or talented young, migrants. People die to come here. We torture those we catch who come by sea to discourage those we do not want. Toowoomba (look it up! It featured in the Avengers and Monty Python!!) won more Olympic medals than New Zealand. We allow the Septics to control foreign policy and depose our prime ministers, but the day is coming when that will stop. We have the highest min wage in the world in ppp.

We reinvented smallpox from DNA. We raise our children to question authority, not to accept it.

We could invite the dominant inhabitants of Israel to live in the West of Australia, with coast line, doubling their land area, leaving the real inhabitants who converted centuries ago, in relative peace. We would hardly notice they were there, but if they behaved they could integrate with our cities too.

Like that great economist A Hitler, we bypassed the banks and printed money: for the Snowy Mountain scheme, avoiding the worst of the “Less Great Depression”. We are in dire need of railways.

Housing? Biggest houses in the world. Anti-social in fact. Many Brits hate the distances to their nearest neighbours. The largest cost is payments to local authorities for land, water infrastructure etc. BrisVegas will double in population in 15 years apparently.

Yeah, we’re real worried, mate!

Australia is alwo the driest inhabitable continent. Yet your main export is really water (which is the main input both in mining and agriculture). Australia is one of the largest (if not the largest) per capita contributors to the global climate change, while at the same time is arguabley the most vulnerable first-world country.

Antarctica is drier. We get the same rain as CONUS.

By warming the world, we also get much of Antarctica!!

I think you may find the Dutch may have to drain the North Sea!

Kaletsky must have a well paying job, and has nevered suffered layoffs or other out-of-work-for-no-good-reason experiences. Else why is he so enamored with the status quo?

His posting is built on the assumption that only the political class and their elites (those who provide the theory or ideology for the politicians) have a say in how a country is run, and that the lower levels do not and should not have any say in the matter. Until, of course, the lower classes force the upper classes to react, and then all hell will break loose and it will be the lower classes who suffer – but that is all right since they forced the elites, etal, to act.

So, even when the elites correctly see something coming, they still can’t (and won’t) ‘get it’. The current expression of unhappiness with the present political system and its ideologies of France, UK, and America, is simply an ‘Arab Spring’ moving into the so-call first world countries.

Canada has certainly earned a place on that list, and indeed if it does not act more decisively to regain control of housing policy/mortgage lending & insurance from banks that have merrily created then passed along enormous risks to the Canadian economy and public purse especially in everything related to housing, the entire oil sector, over-production of cars, whatever, we will end up selling the country for fire wood.