Yves here. Based on the change in the value of sterling this year and since the Brexit vote, it’s clear that Brexit means a weak sterling. No one is quite sure how low it might go, but some forecast that it might fall as low as 1.05 to the dollar.

As most readers know a depreciation of a currency is not always a bad thing. In normal circumstances cheaper currency will make imports more expensive and lead to lower standards of living but it will also make exports cheaper and this will normally lead to more job creation. That’s the theory anyway. If it works out this way a depreciation might help rebalance a current account deficit. The UK could sure do with some rebalancing. It’s current account deficit is now a whopping 5.2% of GDP, the highest it has ever been since the statistics came online.

I’m posting this article that Philip Pilkington wrote in 2014 because it highlights some interesting things about the UK current account and the sterling. Pilkington argues that the sterling is only propped up by financial inflows into the City of London and that any threat to these financial flows can easily result in a sterling crash (he made a similar argument in this Guardian article which came out around the same time). He argues that the UK is not like the US which, because of its reserve currency-issuing status, can run very large current account deficits with little or no consequences for the dollar. The sterling crash after the Brexit confirms his argument: all it took was a big scare.

But this is where the problems come in. As Pilkington shows, last time the sterling took a big hit in 2007-08 export prices didn’t fall and make the UK more competitive, they rose and made the UK less competitive! The reason? Global supply chains. The inputs that UK companies use to make exports are themselves imported. When the sterling falls, the inputs rise in price so the firms have to raise the prices on their export goods. As Pilkington points out this means that all the adjustment must take place on the side of real incomes: that is, peoples’ living standards must fall through rising prices.

By Philip Pilkington. Originally published at Fixing the Economists

Something rather strange happened in Britain around the time of the financial crisis. The sterling tanked, import prices rose substantially and yet the inflation rate didn’t respond as much as we might assume.

Other weird stuff happened too. For example, export prices rose rather than fell and the trade deficit worsened. Although these two aspects seem to totally contradict macroeconomic theory I’m not as concerned about them. In our newly globalised world exports, outside of small open economies, don’t increase as much as economists might assume. I’ve known this since I started examining the data — and Nicholas Kaldor was well aware of this by the late-1970s and early-1980s too. The fact is that in modern developed economies price elasticities don’t matter nearly so much as they did in the past. I have some ideas as to why this is but I won’t get into it here.

I have never, however, come across an instance where a substantial depreciation of the currency has not resulted in substantial price increases in an import-dependent economy like Britain. Indeed, the Office of National Statistics thought that these trends were pretty weird too and so they published an excellent report entitled Explanation beyond exchange rates: trends in UK trade since 2007 which I will draw on for many of the graphs in what follows.

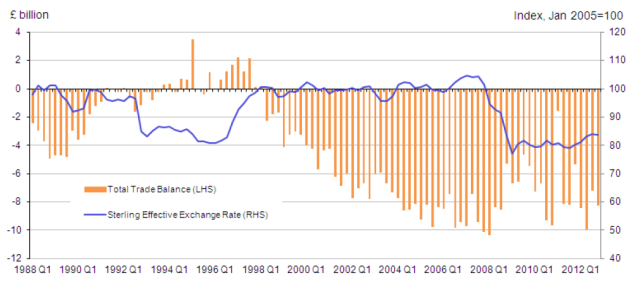

Okay, first of all let’s take a look at the exchange rate versus the trade balance. The period that we are interested in is between 2007 and 2008.

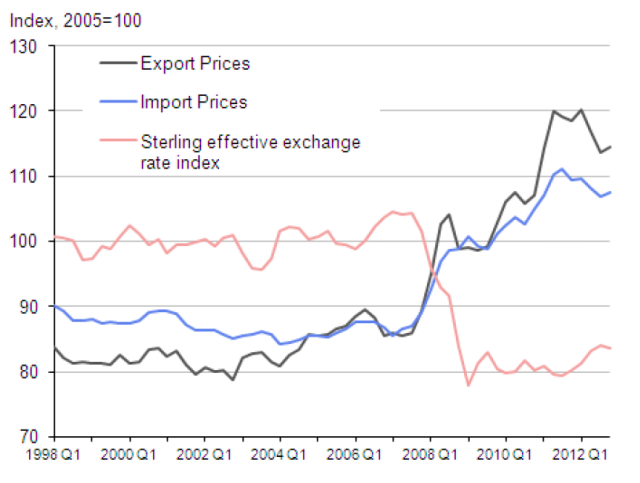

As we can see, there was a massive depreciation around 2007-2008 and the trade deficit stayed open. At the same time import prices went up by a fairly large amount as can be seen in the graph below. Export prices rose too, as we can see — which, of course, is not in line with economic theory.

Now, here’s where the mystery that concerns me comes in: while inflation rose in this period it did not rise as much as I would have expected. CPI inflation did more than double — which is by no means insignificant — but I would have expected it to rise maybe four or fivefold.

So, what is the explanation for all this? Well, I think it runs something like this.

First of all, companies that import goods to use in order produce goods that they export passed on the cost to foreign buyers. As we saw above and in contrast with macroeconomic theory, export prices rose after the depreciation by more than import prices. I think that we are seeing the pass-through effect in the data quite clearly.

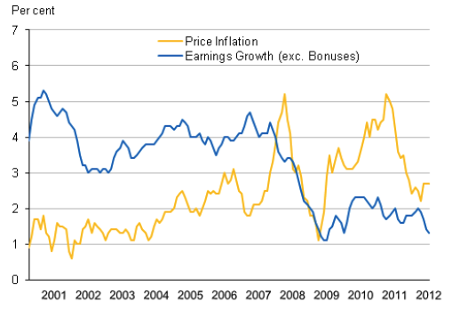

Secondly, and most important from my point of view: companies selling on the domestic market used the sharp fall in wages in this period to absorb the higher costs so that they didn’t have to raise prices and could thus maintain market share. Take a look at the following graph plotting earnings against inflation in this period.

At the same time as firms saw their import prices increase they saw their wage bills fall dramatically. So, they didn’t have to increase prices too much because they just passed through the savings they were making on wage costs. Ultimately workers saw their standards of living fall dramatically but rather than see this manifest as maybe 8-10% price inflation, they saw instead 4-5% inflation and negative real wage growth which went from an average of about +2% to -2% — a decline of about 4%. The net effect on living standards was probably about the same, it just shows up in different data aggregates.

What is the key lesson from this? Well, it seems that the UK didn’t experience substantial price inflation in 2007-2008 after the depreciation of the sterling because of the unemployment and rock-bottom wage growth that occurred at the same time. The effects on actual living standards were probably largely the same as if there had been substantial inflation but you have to look for it in different data.

If a substantial depreciation of the sterling ever took place in a period when there was tight labour markets and healthy wage growth we would likely see a large uptick in inflation. We would also see feedback effects in that the trade deficit would rise as price rises were passed through to foreign buyers which would then put further pressure on the currency. The whole thing could get very ugly very quickly. And that’s not even to raise the specter of a wage-price spiral in a time of low unemployment.

This brings us to our final question: why was there a large depreciation of the sterling in this period? Well, because the value of the sterling is tied up with the price and turnover of financial assets in the City of London. The UK is not in a position like the US which has the world’s reserve currency and so when asset prices took at massive hit in 2007-2008 the sterling did too. This shows just how sensitive the sterling is to any chaos that might occur in the financial markets. It also shows just how sensitive the currency would be if a government ever moved to shut down the City.

The UK economy after Thatcher is hooked on finance. And it would take quite a bit of policy ingenuity to ween it off its drug of choice.

Currently the UK’s Consumer Prices Index is rising at a feeble 0.3% over the past 12 months.

If a swingeing sterling devaluation don’t push it up to parity with the US (1.0%) by the end of the year, then I just don’t know what the hell it would take.

One promising sign: the old yellow dog (gold) popped 15% overnight in sterling terms.

Special hat tip to a prominent blogger who posted a Bloomberg commentary yesterday titled “I Don’t Hate Gold. I Just Don’t Love It.”

George Soros in a Guardian article a few days ago predicted a devaluation of sterling in excess of 15% if Brexit took place. I think he had this in mind. He also pointed out that there is no scope to cut interest rates further which further undermines any benefit to the economy.

Link to the George Soros article.

The man has a history of seeing around financial corners.

Previous inflation, was cost push, not wage pull, and was systemic because the cost push was energy cost driven.

In addition wages were indexed giving the appearance of wage pull inflation. When the wage indexing was broken, by Thatcher, so was inflation, and demand.

It is interesting to note the financial area of the UK was Brendon, and the manufacturing area Brexit.

The results in Scotland and N. Ireland are a result of hundreds of years of kind, considerate and gentle rule from Westminster.

To mitigate then effect of Brexit the UK government should reinstitute tariffs, and a policy of Made in Great Britain.

During the financial crisis, Brit guv debt skyrocketed due to the bank bailout. Sterling dropped about 30% as a result.

Britain was/is even more financialized than the US. Transitioning is going to take time and be painful.

I expect the same here if we ever try to get our real economy back, when our “manufactures” need to do more again besides putting near finished goods into retail packaging and stamp a logo on it.

If the pound sterling falls, and the cost of British exports does not also fall because the costs of imported precursors is priced in foreign currencies, that would suggest to me that British ‘industry’ has been so hollowed out that it hardly exists in any real form. I mean, if a British car company ‘manufactures’ a car by importing engines, transmissions, brake assemblies, etc., bolting them together, and then exporting them, the value added in Britain is just a small amount of labor required to assemble these components. In that case a falling currency would not be expected to lower export costs significantly.

It is often said that ‘free’ trade is a race to the bottom. If the inputs for building things are freely available across the world, and the only thing that a nation has to add is domestic labor, then the only thing that can fall in price is domestic labor.

On the other hand, a nation with substantial domestic resources, and large integrated supply chains, that makes things that are relatively unique and that other nations can’t easily build by just bolting widely available assemblies together, would get lower export prices after a currency devaluation.

So maybe this says more about the physical structure of British manufacturing than finance per se.

Countries that can’t make an honest living grow their financial sector.

Dang, I guess that means buying a new Bentley or Rolls Royce in the USA will get more expensive. That’s not what the cheaper 1% were hoping for with the sterling getting pounded.

Not necessarily, they farm the cattle used to make the leather seats next to the assembly plant, :-)

Germany and China have sucked up such a huge share of global manufacturing it would be hard to change with just currency.While China has lost some apparel that is a return to countries China had taken it from mostly Africa.I recall the Chinese got us to change a rule that we had that helped Africa plus the manufacturing we sent them . Our imports from China have fallen a lot….so have our imports from Germany ….which did rise because it got a cheap currency and sucked out manufacturing from the crest of Europe. I wish they was better data but I base this on our sources of imports …..the rise of China is clear.

>First of all, companies that import goods to use in order produce goods that they export passed on the cost to foreign buyers.

Ah, finally real-world understanding. All manufacturing really does, can do, is take a swag at pricing. So our shop, just as a for instance, essentially multiply our parts costs by X and hope for the best (ok, we’re a little cleverer than that, we then tune from there — but there is quite a bit of labor involved so how this keeps working is a mystery but there it is, 3 decades now). If we release a product we see as an advance from what our competitors have, we stick on a bit of a premium and… well again hope for the best.

So yeah, if my inputs are 100 quatloos (a mix of domestic and imported), and X is like 2.17 and they suddenly change to 108 quatloos, then my asking price will go from 217 to 234 quatloos. And I will take a deep breath and see what happens. Note if that holds my profit goes up, and I become a more significant exporter!

I’m not saying that price discovery doesn’t finally occur, but it’s a really uneven process full of clunking and banging.

The question is: did the pricing eventually fall? Answer: depends on the competition, of course.

>so the firms have to raise the prices on their export goods.

Oh, I forgot to add: no we f*cking don’t “have to”. We just wind up doing so b/c it’s built into the system, like I said. If x+y = z and x goes down then z also goes down. Duh. It’s just surprisingly few people are bothering with that equation. We all just use a cost multiplier.

That is what inflations is and what it does. Yet we have many who argue for inflation?

We had inflation in the 1970s and worker incomes kept pace. Volcker was very explicit when he raised interest rates to the sky and caused a very nasty recession in the early 1980s that labor needed to “get the message”. Reagan then went to work on weakening unions, which has continued to this day.

Inflation is never perfect inflation (everything inflating at the same rate). Who wins and loses depends on which prices rise relative to other prices, as well as changes in the rate of infaltion.

Prices of financial assets have an assumed rate of inflation built into their price. Capitalists win if inflation falls lower than at the time of their purchase and loses if it rises (we have some exceptions when the Fed lower real interest rates below the rate of inflation but you see how this principle works in general).

What makes you think that wages will rise at the same pace as inflation? If wages don’t rise, and I don’t see any indication they will, then inflation does not help.

If it’s wage push inflation, almost by definition. If it’s supply side inflation, then the only way to prevent it would be to either improve productive capacity/efficiency or to cause enough unemployment that people can’t afford to buy goods and services.

In either case, inlfation is not really a big deal. In the supply side scenario puchasing power might go down, but if the resource consumption must go down, it is better it goes down via inflation than via mass unemployment.

The Chapwood Index covers 50 metro US areas and updates prices on a basket of essential goods and services in each area. Over the past 5 years, across all areas, this Index concludes that inflation has ranged between 7-10% per annum which, on a compounding basis, indicates that prices have almost doubled during this period. Certainly, wages have no where near kept pace; in fact they have actually fallen.

The inputs that UK companies use to make exports are themselves imported. When the sterling falls, the inputs rise in price so the firms have to raise the prices on their export goods.

Depends on the export good. I took advantage of the GFC-era pound-sterling drop to buy a case of my favorite Islay single malt from a Scottish distributor, at roughly half the dollar price US chains like BevMo were charging (and which did not budge in response to the currency swing). This echoes TG’s comment above.

inflation causes the standard of living of the common folk to decline?

sounds like common sense.

economists seem to get it so its time to go home.