Lambert here: The graphics are less than ideally executed, but they’re explained in the text, and a lot of people have concerns about this topic.

Hiro Ito, Professor of Economics, Portland State University, Masahiro Kawai, Project Professor, Graduate School of Public Policy, University of Tokyo. Originally published at VoxEU.

China’s authorities have been promoting the renminbi as an international currency for international trade, investment, and finance. This column examines the experiences of the dollar, yen, and deutschmark from the 1970s to the 1990s. As long as China’s neighbouring economies keep using the dollar for international trade and financial activities, the rise of the renminbi as a trade invoicing currency may be as fast as the rise of China itself.

In recent years, China’s authorities have been promoting the renminbi (RMB) as an international currency for international trade, investment, and finance. Considering that the country is the world’s second largest economy and has been the biggest trader for the last decade, this initiative is natural. While the recent admission of the RMB to the IMF’s special drawing rights basket is an important first step for the currency to become a major reserve asset, it is unknown what kind of international currency it will become. The RMB could become a global currency like the dollar, while it may not become the currency of last resort (Prasad 2014). The RMB might become a regional currency like the euro today or the deutschmark in pre-1999 Europe. Or, it might fail to become either a global or a regional currency, as has been the case with the Japanese yen.

While one cannot predict the future of the RMB, some lessons can be learned from history. Several researchers have examined how much national currencies are used for invoicing international trade.1 Currency invoicing for trade is an important first step for any national currency to become a major international currency. As Ito et al. (2015) find for the use of the dollar and the euro in Eastern Europe, the more a currency is used for trade invoicing, the more it tends to be held in official foreign reserve assets.

In a new paper, we conduct an empirical analysis of currency choice for trade invoicing by focusing primarily on the experiences of the dollar, yen, and deutschmark for the period from the 1970s to the 1990s (Ito and Kawai 2016). The purpose of our exercise is to provide some insight into the future potential for, or impediments to, the RMB becoming a major trade invoicing currency.

Stylised Facts of Currency Choice for Trade Invoicing

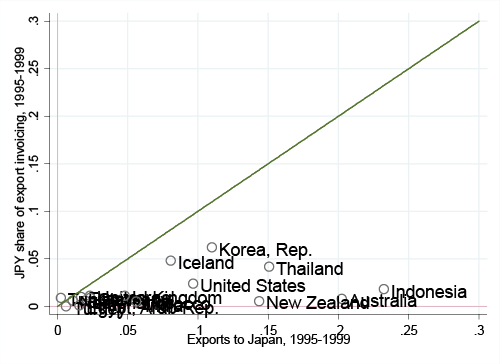

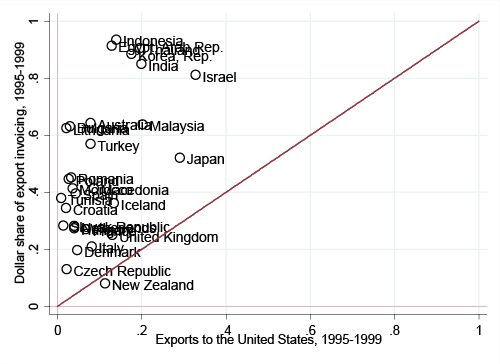

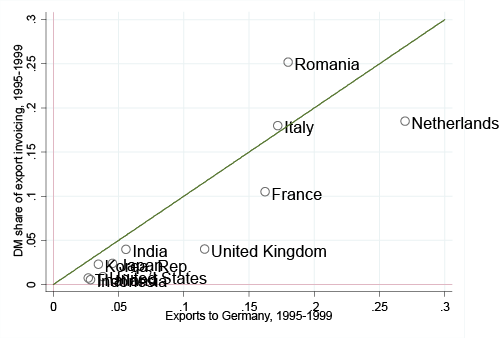

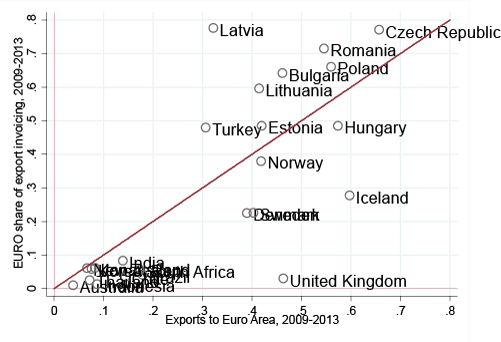

Figure 1 provides useful insights into the use of a major currency for trade invoicing relative to countries’ export dependence on the major-currency country.[2] The figure illustrates the share of a major currency in sample countries’ export invoicing against the share of those countries’ exports to the major-currency country in total exports for the 1995-1999 period (the 2009-2013 period in the case of the euro). The figure shows that the share of yen invoicing is quite small and much less proportional to the share of Japan as a destination of partners’ exports. In sharp contrast to the yen, US trading partners tend to invoice their exports in dollars much more than the proportion to the share of their exports to the US, indicating the dollar’s dominant role as a trade invoicing currency. The deutschmark is an intermediate case between the dollar and the yen – Germany’s trading partners tend to be distributed close to the 45 degree line, suggesting invoicing was driven mainly by the strong trade ties with its neighbouring countries. Clearly, the deutschmark was a regional currency.

Figure 1. Major currency share and export share for major-currency country’s trade partners

(a) Export share with Japan and yen invoicing

(b) Export share with the US and US dollar invoicing

(c) Export share with Germany and DM invoicing

(d) Export share with the Eurozone and euro invoicing

The euro invoicing pattern (over the 2009-2013 period) falls in between deutschmark and dollar invoicing. Its share of export invoicing fully reflects partners’ export share with Eurozone economies. For Eastern European countries, however, the euro share is even higher than the export share as in the case of the dollar.

The reasons for the dollar’s dominant role as an invoicing currency are obvious. The US has been the largest trading nation for a long time and the deep, broad, and liquid dollar financial markets have made it beneficial for trading partners to use the currency for trade invoicing. Furthermore, the formation of US dollar zone economies (i.e. economies that use the dollar heavily for trade, investment, financial, or currency policy purposes) also contributes to the wide prevalence of dollar invoicing.3

The sharp contrast between the deutschmark and the yen can be explained by several factors. For one, Germany was surrounded by countries with per capita income levels that were relatively similar to and even as high, whereas Japan was surrounded by developing and emerging economies which had per capita income levels that were much lower.4 Given the size of the German economy and its stable macroeconomic management, many European firms, which conducted intra-industry trade in the region, naturally selected the deutschmark for trade invoicing in the region. This practice was undoubtedly facilitated by deep economic and financial integration in the region.

In contrast, the Asian region relied heavily, and still does, on the dollar for invoicing international trade of goods and assets. More importantly, Japan was, and has been, surrounded by dollar-zone economies which were and have been highly dependent on the US market for trade and therefore willing to invoice or settle their trade in the dollar.5

Regression Analyses

In our paper, we have conducted panel regression analysis to examine the determinants of the shares of major currencies, such as the dollar, yen, deutschmark, pound, and Swiss franc, used for trade invoicing by third economies, i.e. economies other than the major currency countries. The estimation results have confirmed several interesting points. First, the share of a major currency for trade invoicing is positively affected by these economies’ export shares with the major-currency country, but this does not apply to the dollar, that is, the use of the dollar is not necessarily driven by trade ties with the US. Second, the share of a major currency for trade invoicing is negatively affected by financial development and openness in third economies, reflecting that an economy with a more developed or a more open financial market tends to invoice its export in its own (home) currency. Third, an economy with a high commodity trade ratio tends to invoice its export predominantly in dollars. Economies with macroeconomic instability tend to invoice trade in the deutschmark, indicating that these economies regard the deutschmark as an anchor currency.

We have conducted another regression analysis by using major-currency weights in the implicit currency baskets of third economies as well as the shares of trade with major-currency zones for each sample economy as explanatory variables. We find that both the major-currency weights and trade shares with different currency zones affect the major currency share used for trade invoicing. For example, the tendency to invoice trade in dollars (or deutschmark) becomes stronger in economies that belong to the dollar (or deutschmark) zone. In addition, if an economy has large trade ties with such dollar (or deutschmark) zone economies, it tends to invoice its trade in the dollar (or deutschmark). These results suggest that the reason why the deutschmark was firmly established as a regional currency in pre-1999 Europe is that many European countries belonged primarily to the deutschmark zone and actively used the DM as the main invoicing currency for trade. In contrast, because most of Japan’s neighbouring economies belonged to the dollar zone, the yen was not, and still is not, widely used as a trade invoicing currency, explaining the yen’s substantially low share in trade invoicing even by Asian economies.

We have also examined how conditions in the major currency countries (excluding the US) affect the use of their own currencies. We find that the non-US major currency countries tend to invoice their trade in their own currencies when they have a large presence in world trade and have high levels of per capita income.[6]

We also find that a major currency country with a more open financial market tends to invoice its export more in its own currency. However, financial development alone does not lead to own-currency invoicing unless it is associated with a high level of financial market openness. Furthermore, a major currency country with higher shares of trade with dollar zone economies tends to invoice its trade less in its own currency.

Implications for RMB internationalisation

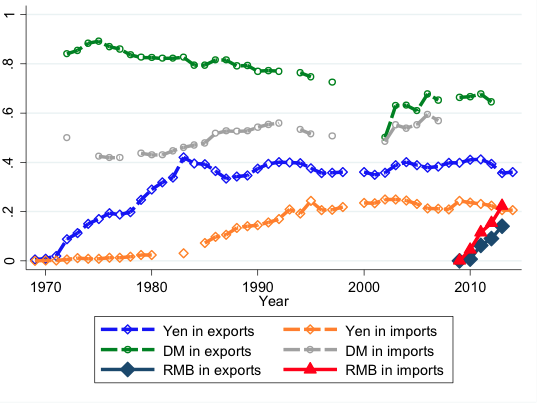

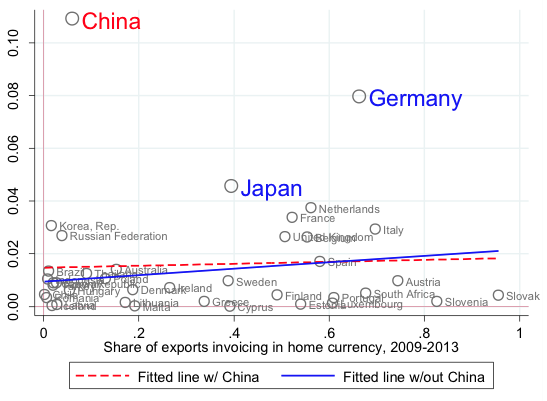

What do our empirical findings suggest for RMB internationalisation? The use of RMB as a settlement currency has risen sharply since its liberalisation in 2009 (Figure 2). However, it is not as high as what China’s trade share in the world suggests (Figure 3). It is unclear whether the RMB will be used as prevalently as the deutschmark was or the euro is at present.

Figure 2. Home currency invoicing/settlement for export and import: Japan, Germany, and China

Note: The deutschmark share after 1999 is replaced with the euro share in Germany’s exports and imports.

Figure 3. Home currency invoicing and the world export share, average 2009-13

China’s rise as a large trading nation and the growth of its per capita income will contribute to greater use of the RMB for trade invoicing. However, it is uncertain whether financial liberalisation, deregulation, and opening will advance smoothly, considering the way the Chinese financial authorities intervened in the financial markets in the midst of massive capital outflows in 2015 and early 2016. More importantly, just like Japan, China is surrounded by economies that belong to the dollar bloc. This will pose a difficult challenge for RMB internationalisation. As long as China’s neighbouring economies in Asia keep using the dollar for international trade and financial activities, the rise of the RMB as a trade invoicing currency may not take place as fast as the rise of China as an economic and trading power.

References

Ito, H. and M. D. Chinn (2015) “The Rise of the ‘Redback’ and China’s Capital Account Liberalization: An Empirical Analysis on the Determinants of Invoicing Currencies.” In Eichengreen, B. and M. Kawai, eds., Renminbi Internationalization: Achievements, Prospects, and Challenges (January 2015).

Ito, H. and M. Kawai (2016) “Trade Invoicing in Major Currencies in the 1970s-1990s: Lessons for Renminbi Internationalization,” RIETI Discussion Paper, 16-E-005.

Ito, H., R. McCauley, T. Chan (2015) “Emerging Market Currency Composition of Reserves, Denomination of Trade and Currency Movements.” Forthcoming in Emerging Markets Review (October 2015).

Ito, T., S. Koibuchi, K. Sato, and J. Shimizu (2010) “Why the Yen Failed to Become a Dominant Invoicing Currency in Asia? A Firm-Level Analysis of Japanese Exporters’ Invoicing Behavior.” NBER Working Paper No. 16231. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kawai, M. (1996) “The Japanese Yen as an International Currency: Performance and Prospects.” In Ryuzo Sato, Rama V. Ramachandran, and Hajime Hori, eds., Organization, Performance and Equity: Perspectives on the Japanese Economy, Boston, London, Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 305-355.

Krugman, P. (1980) “Vehicle currencies and the Structure of International Exchange,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 12(3): 513-26, August.

Goldberg, L. and C. Tille (2008), “Vehicle Currency Use in International Trade,” Journal of International Economics 76(2): 177-192, January.

Goldberg, L. and C. Tille (2009), “Macroeconomic Inter-dependence and the International Role of the Dollar,” Journal of Monetary Economics Volume 56:7, October 21.

Kamps, A. (2006), “The Euro as Invoicing Currency in International Trade,” European Central Bank Working Paper Series No. 665. European Central Bank (August).

Prasad, E. (2014), The Dollar Trap: How the U.S. Dollar Tightened Its Grip on Global Finance, Princeton University Press.

Endnotes

[1] See Goldberg and Tille (2008, 2009), Kamps (2008), and Ito and Chinn (2015) among others.

[2] In this study, we use the updated and expanded version of the dataset initially constructed by Ito and Chinn (2015). This new dataset includes the shares of major currencies used for trade invoicing and settlement. The currencies included are the dollar, euro, Japanese yen, UK pound, deutschemark, French franc, Italian lira, Dutch guilder, Swiss franc, “home currencies,” and others. It covers 56 economies, both developing and emerging economies, and going back to the 1970s for Europe’s major countries, the Republic of Korea, and Japan.

[3] “Inertia” has also helped the U.S. dollar in maintaining its dominant role (Krugman, 1980).

[4] Ito and Chinn (2015) find that countries with higher per capita income tend to have lower shares of dollar export invoicing and higher shares of invoicing exports in their own home currencies.

[5] Many firms in the region have tried to protect their competitiveness in the U.S. market by “pricing to market,” i.e., invoicing their exports in the dollar (Goldberg and Tille, 2008; Ito et al., 2010). Japan’s large trading companies (known as sogoshosha) and multinational firms have developed strategies to minimise exchange risks when conducting trade in U.S. dollar. They have been pooling risks, marrying claims and liabilities, and borrowing and lending in foreign currencies, including the U.S. dollar, on a global scale, so that they have had no strong incentive to invoice trade in yen (see Kawai, 1996, Ito, et al., 2010).

[6] The level of per capita income tends to be highly correlated with the level of differentiation in goods and services a country produces and, thus, the country’s bargaining power to invoice trade in its home currency.

Seems there’s a rather serious typo in the byline:

“As long as China’s neighbouring economies keep using the dollar for international trade and financial activities, the rise of the renminbi as a trade invoicing currency may (NOT) be as fast as the rise of China itself.”

At the expense of showing my ignorance here, is there any real advantage to China in having RMB as a more widely used currency? We’ve already seen how false invoicing has allowed a steady and strong outflow of wealth from the country – so far, its manageable, but it seems to me that the more internationalised the RMB is, the more constrained the government is in using currency controls as a tool of domestic policy. If the RMB becomes fully internationalised, they really have only interest rates left as a tool of control, which in such an indebted economy will surely mean huge trouble if they have to raise rates in order to stop a run on the RMB in some future crisis.

The Triffin Dilema suggests China can’t have it “just right”. The porridge doesn’t work that way.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triffin_dilemma

For a moment I thought you said a ‘Tiffen Dilemma’, and I remembered I haven’t made lunch yet…