By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

There is no better proof of Kenneth Arrow’s thesis that college degrees signal salary expectations (“conveying information to the purchasers of labor”) — and not actual education[1] — then the way college and university administrators treat the great majority of people actually doing the educating: Like garbage. I discovered this in my first years up here, when I did some adjunct teaching at the university; I worked out my hourly rate, including not just classroom time, but prep, meetings, and grading, and it came to $8.00 an hour, before taxes; that is, when I caffeinated myself with a large latté for class, I used up a little over a quarter of what I made for that class. As a rational economic actor [snort], I would have been better off as a barista. “This is the value we place on educating our children,” I thought[2]. No health insurance, of course (until after, IIRC, three years).

Welcome to Neoliberal U!

Neoliberal U

The degradation of the university under neoliberalism has been obvious for decades to anyone except, well, the top 10% who have directly benefited from it[3]. MIT’s Noam Chomsky summarizes the process well, in terms that will be very familiar to readers:

When universities become corporatized, as has been happening quite systematically over the last generation as part of the general neoliberal assault on the population, their business model means that what matters is the bottom line. The effective owners are the trustees (or the legislature, in the case of state universities), and they want to keep costs down and make sure that labor is docile and obedient. The way to do that is, essentially, temps. Just as the hiring of temps has gone way up in the neoliberal period, you’re getting the same phenomenon in the universities…

Crucially, by not guaranteeing employment, by keeping people hanging on a limb than can be sawed off at any time, so that they’d better shut up, take tiny salaries, and do their work; and if they get the gift of being allowed to serve under miserable conditions for another year, they should welcome it and not ask for any more….

That’s one aspect, but there are other aspects which are also quite familiar from private industry, namely a large increase in layers of administration and bureaucracy. If you have to control people, you have to have an administrative force that does it. So in US industry even more than elsewhere, there’s layer after layer of management—a kind of economic waste, but useful for control and domination. And the same is true in universities. In the past 30 or 40 years, there’s been a very sharp increase in the proportion of administrators to faculty and students; faculty and students levels have stayed fairly level relative to one another, but the proportion of administrators have gone way up. There’s a very good book on it by a well-known sociologist, Benjamin Ginsberg, called The Fall of the Faculty: The Rise of the All-Administrative University and Why It Matterss (Oxford University Press, 2011), which describes in detail the business style of massive administration and levels of administration—and of course, very highly-paid administrators. This includes professional administrators like deans, for example, who used to be faculty members who took off for a couple of years to serve in an administrative capacity and then go back to the faculty; now they’re mostly professionals, who then have to hire sub-deans, and secretaries, and so on and so forth, a whole proliferation of structure that goes along with administrators. All of that is another aspect of the business model.

But using cheap labor—and vulnerable labor—is a business practice that goes as far back as you can trace private enterprise, and unions emerged in response. In the universities, cheap, vulnerable labor means adjuncts and graduate students. Graduate students are even more vulnerable, for obvious reasons. The idea is to transfer instruction to precarious workers, which improves discipline and control but also enables the transfer of funds to other purposes apart from education.

(Thomas Frank would remind us that the “layer after layer of management” comprises members of the 10%: the credentialled[4] and well-paid professional class. I’m guessing that most of them, at least in the university setting, are liberal goodthinkers and Clinton supporters.) And the temps — the adjuncts and grad students — have been dubbed “the precariat,” because as contingent labor, their lives are precarious (and that’s not a bug. It’s a feature). Here are the numbers:

The fact is, according to the Coalition on the Academic Workforce, of the nearly 1.8 million faculty members and instructors who made up the 2009 instructional workforce in degree-granting two- and four-year institutions of higher education in the United States, more than 1.3 million (75.5%) were employed in contingent positions off the tenure track, either as part-time or adjunct faculty members, full-time non-tenure-track faculty members, or graduate student teaching assistants.

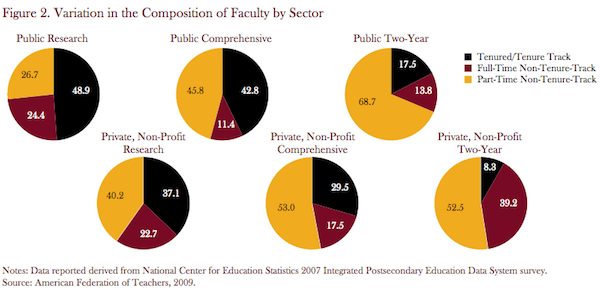

And here are numbers in the form of a chart (the University of California’s Pullias Center for Higher Education):

And here are the wages:

Based on a survey of nearly 20,000 non-tenure-track faculty, the report found that teaching was the primary occupation for a large majority of respondents, but two-thirds received an annual income of less than $45,000. Over half received less than $35,000.

(In other words, half the academic precariat, makes less than a high-end Walmart cashier or Pharmacy Technician, and a Walmart Sales Asssociate, at $25K, is in striking distance. And you don’t have to load yourself with a life-time of debt to work at Walmart!)

By contrast, if you’re an academic administrator, life is good. Chomsky identifies one key function of administration: Control of the labor force. A second is to optimize the curriculum for corporate purposes. A third is to think of departments as profit centers and triage those that don’t bring in the bucks. (The “innovation” [snort] program at Penn State I described yesterday, with its winners, losers, and mentors, has the ethos and structure of a football program. I don’t think that’s a coincidence.) And a fourth is to feather their own nests at the expense of the faculty who actually deliver real value to students. From a review of Ginsberg’s The Fall of the Faculty:

In prose that is by turns piquant, sarcastic and largely dismissive of many administrators, Ginsberg marshals anecdotes from his 40 years of experience at Hopkins and Cornell University, as well as from accounts from other campuses. He juxtaposes these with historical analysis and data showing that the growth in the ranks of administrators (85 percent) and associated professional staff (240 percent) has far outstripped the increase in faculty (51 percent) between 1975 and 2005. “Generally speaking,” he writes, “a million-dollar president could be kidnapped by space aliens and it would be weeks or even months before his or her absence from campus was noticed.’

Amen.

Ginsberg lays at administrators’ feet a host of perceived [by which we mean “real”] ills: the increased curricular focus on vocational education instead of one grounded in the liberal arts; an emphasis on learning outside the classroom in lieu of core academic disciplines; the transformation of research from an instrument of social good and contributor to human knowledge to an institutional revenue stream; and the limiting of tenure and academic freedom.

The larger result, he argues, is that universities have shifted their resources and attention away from teaching and research in order to feed a cadre of administrators who, he says, do little to advance the central mission of universities and serve chiefly to inflate their own sense of importance by increasing the number of people who report to them. “Armies of staffers pose a threat by their very existence,” he wrote. “They may seem harmless enough at their tiresome meetings but if they fall into the wrong hands, deanlets can become instruments of administrative imperialism and academic destruction.”

Is all this corrupt? I think it is. The administrative parasites who have injected their neoliberal venom into the host body of higher education, paralyzing and then controlling it, are converting a public institution to serve private purposes[5s]. The administrative layers of our colleges and universities should be gutted, and the resulting revenues devoted to the original, ancient, public functions of the university: Teaching and research. (Frankly, I don’t know why our own Governor LePage doesn’t do exactly that in the great state of Maine: We have a bloated “University of Maine System,” and nobody’s ever been able to figure out what it does, and we’ve got deans and deanlets up the wazoo. Fire them, give half the money to the students in the form of a break on tuition or debt relief, and give the other half to the faculty, (a) giving youth a reason to vote Republican and (b) nuking the Democrat administrators on the public teat. Democrats yammer a lot about LePage, but for all that, he’s never assaulted their institutional base.)

With this background, let’s look at the adademic precariat, which comes in two forms: adjuncts, and teaching assistants, who just won a victory at the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

Teaching Assistants

Washington, D.C. — The National Labor Relations Board issued a 3-1 decision in Columbia University that student assistants working at private colleges and universities are statutory employees covered by the National Labor Relations Act. The Graduate Workers of Columbia-GWC, UAW filed an election petition seeking to represent both graduate and undergraduate teaching assistants, along with graduate and departmental research assistants at the university in December 2014. The majority reversed Brown University (342 NLRB 483) saying it “deprived an entire category of workers of the protections of the Act without a convincing justification.”

For 45 years, the National Labor Relations Board has exercised jurisdiction over private, nonprofit universities such as Columbia. In that time, the Board has had frequent cause to apply the Act to faculty in the university setting, which has been upheld by the Supreme Court.

Federal courts have made clear that the authority to define the term “employee” rests primarily with the Board absent an exception enumerated within the National Labor Relations Act. The Act contains no clear language prohibiting student assistants from its coverage. The majority found no compelling reason to exclude student assistants from the protections of the Act.

So now, teaching assistants in private universities have the minimum baseline of being able to organize[6] (that those in public universities have always had). Now comes the hard part: Negotiating, and dealing with continued union busting by the administration. Here’s the immediate reaction from the Columbia; they’re not giving an inch. They’re even denying that the NLRB has “the authority to define the term ’employee’,” as they trot out the shopworn messaging about “scholarly training”:

Columbia Provost sent this incredibly antagonistic, anti-union email out to the entire university community today pic.twitter.com/tyRHEGFswn

— Julia Carmel (@JuliaCarmel__) August 25, 2016

Corey Robin (Facebook, sorry) reacts:

It is great that the Obama White House appointed people to the NLRB who made this pro-grad student decision today. Like Bill Clinton did more than a decade ago (a decision that Bush’s NLRB overturned). On the other hand, the reason we need the NLRB to make these decisions is the vicious union-busters at private universities who won’t allow grad workers to organize—many of whom (the union-busters, that is) have deep and very close ties to Obama and Hillary Clinton. For example, Jacob Lew, who was Obama’s Chief of Staff and is now his Treasury Secretary, was John Sexton’s point person at NYU in busting the union in the late aughts [here]. Likewise, Cheryl Mills who went onto be Hillary Clinton’s chief of staff when Clinton was Secretary of State [here]. At Yale in the early 1980s, the Yale trustees who forced a bitter, months-long strike of clerical workers, many of them women, and service and maintenance workers, included longtime Democrat and feminist Eleanor Holmes Norton [here]. As important as the NLRB ruling today is, anyone who knows anything about union-busting, especially at elite universities, knows that the ruling is not nearly enough, that trustees at Harvard, Yale, Columbia, Brown, Cornell, and elsewhere—many of whom, I’m sure, have ties to high-ranking people in the Democratic Party, including Obama and the Clintons—are going to need external pressure, not just from workers and progressive activists but also from these elite officials. So, yes, welcome the NLRB ruling and all that produced it, but let’s remember that the reason we needed these Obama/Clinton NLRB rulings at the level of the state has everything to do with how the Obama/Clinton forces operate in the private sector.

(And who could forget that Bill and Hillary (née Rodham) Clinton crossed a picket line at Yale and did scab labor on their first date?) Here’s material on union busting at Harvard, Duke, Northeastern. The adminstrators are not going to stop union busting. After all, they’re paid to do it, they’re ideologically committed to it, and their financial security depends on it. “This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end….”

Adjuncts

Now let’s move on to the other portion of the university precariat: Adjuncts. We’ve seen the numbers, and how and why adjuncts have come to dominate the university teaching workforce at Neoliberal U; here are some of their stories. How I Woke Up and Realized I Was Adjunct: An Adjunct Narrative from the Age of Neoliberalism:

I am, by neoliberal, administrative definition, non-essential. How did I get here, to this dark and hopeless dead end, to the outer deck of this sinking ship?

It took more than fifteen years, but I finally woke up and realized that I’m trying to win the lottery. I have the proverbial snowball’s chance in Hell of getting a tenured position. I have been adjunctified. I am adjunct. Disposable.

The ideology of the market that seeks to commodify all and everything defines me as non-essential and makes me a precarious worker. Some tell me that I chose my fate and that if I don’t like my wages I should find another job.

But I see that what I do is important for the maintenance of civilization. If higher education continues to devolve into corporate job training, our democracy will disappear, eventually. Without the ability to think and communicate clearly, without the humanistic values that enter into society through a liberal arts higher education, without the deep understanding of science available in college, in thirty years (or so) when the climate destabilization beast really gets angry, Hell will break loose. Ah! The rough beast slouching towards the Ivory Tower! The widening gyre! The sinking ship!

I am defined as non-essential, I am serially unemployed, financially challenged, but I know that I’m needed because I have been called back and given a “tentative agreement” over thirty times. I know I make a difference because students tell me. The value of my contribution is not contingent or non-essential but my status and pay is. The adjunct me is different from what should have been the full-time me only in that he gets less than half the pay. At the very least, I deserve to be paid as well as if I were full-time.

But my experience as a [visiting professor] at four different institutions over the last 15 years has made clear that the ideals that I’ve been sacrificing myself for – freedom of inquiry, the exploration of human potential, providing opportunity to others – exist far more in theory than in reality in our system of higher education.

These ideals as to the purpose and potential of education are mainly in my head. I have been working for a fantasy.

It has been easy to maintain this fantasy when so many others I am working alongside harbor it as well, making their own sacrifices in the name of the ideals we claim as most precious.

But this is a delusion. The institutional framework of higher education has little care for the things I find most meaningful, that are most important. I can pursue them in my classroom, and as adjunct, this is all that matters.

I longed for the chance to try to bring reality closer to that ideal as a full-fledged member of the team, but this is apparently not my destiny. I suppose time will tell if I dodged a bullet in not getting what I figured for my dream job.

The start of the semester usually brings that combination of excitement and trepidation so many instructors know well, the sense that something big and involving is starting, a mountain to be climbed.

That feeling is gone. Teaching will be a relatively small portion of my workload. It will have to be since I have to try to make up for the lost income. My life suddenly has more possibilities in front of it, more room to explore, to say yes to new things.

I didn’t want any of that, though. I wanted to teach, to mentor, to learn.

Maybe I need to change the title of the blog to “Just Adjuncting.” It doesn’t have the same ring, though, and as of yet, I don’t know what “Just Adjuncting” means.

Ultimately, of course, “just adjuncting” must have a corrosive effect on the student-teacher relationship. McSweeney’s:

Classic College Movies Updated for the Adjunct Era.

Good Will Hunting

MIT Professor Gerald Lambeau is impressed by the intellect of Will Hunting, a janitor who solved an extremely difficult math problem, but Will needs help processing his complex emotions and anger. Lambeau turns to his estranged former college roommate, Dr. Sean Maguire, for help. Sadly, Maguire, an adjunct professor who must shuttle between three campuses in two states and teach 7 classes a semester to stay off the dole, can’t find a minute to call Lambeau back. Will ends up in jail by the age of 23, Lambeau never goes out on a limb for another student, and Maguire is fired for being late to class because of a car pile-up on I-90.

(The neoliberal response to stories like these is that “PhD’s are oversupplied” Or, in expanded form: “There are just too darn many smart hardworking people studying the subjects they love!” I would question matters on the demand side. Is our society so sclerotic that it can’t find work for these people?)

Given terrible wages and degrading working conditions, it’s not surprising that so many adjuncts are organizing, and successfully. From the Boston Globe:

Adjunct professors unionize, revealing deeper malaise in higher ed

Yet more than 40 percent of the teachers at US colleges and universities are adjuncts — part-time faculty members who are paid by the course. Like TaskRabbits and Uber drivers, these instructors are in the vanguard of an unpredictable freelance economy. …

Recently, adjunct faculty members at Duke University voted to affiliate with the Service Employees International Union, following a trend that’s gained particular force in Greater Boston, the nation’s higher education capital. Adjuncts at Tufts, Lesley, Northeastern, Boston University, and other schools have voted to unionize. Some contracts are in force; others are in various stages of negotiation. Longtime Lesley adjunct Celia Morris, the president of the SEIU’s higher education unit for the Boston area, expects to have 3,500 members soon.

As unionization efforts multiply, university administrators are apprehensive, and understandably so. While unionization drives began with adjuncts, organizers have extended the campaign to groups, such as nontenured but salaried full-time instructors at BU, whose concerns are less sharply defined.

There’s a lesson here for universities: They’ve backed into a business model that relies on a steady supply of underemployed instructors. And if the angst of adjuncts alone doesn’t persuade schools of the need for change, maybe the growing presence of union organizers will.

Will the universities learn that lesson? Possibly. But it’s the adjuncts who are going to have to help the administrators attain enlightment: with the Zen Slap of organizing. (As of this writing, I can’t find figures on how many adjuncts are organized; what’s certain is that efforts by SEIU and others are really bubbling.)

Conclusion

Here’s one more story about wages and working conditions for the academic precariat, from Academia is Killing My Friends:

I’ve got a history MA, and I was asked to come back and adjunct even while I was still a teaching grad assistant. It’s been years, now, and I love it. I love teaching. I love lecturing. … But I can’t do it any more.

I can’t keep making $10,000 a year teaching part-time, and I can’t afford the gas and parking to teach at more than one school (they’re too spread out, around here). I can’t keep dragging down my wife by working so hard to get paid so little, and I can’t keep doing what I love, and what I’m good at, because it just doesn’t pay the bills.

Going after a PhD feels like throwing good money after bad, but I know without a PhD I’ll never make full-time.

So here I am. The fall semester will be it for me, in academia. As I sit here and read another semester’s worth of fantastic student course evaluations, it guts me, because I know this is almost it. It’s almost over. The career that I threw so many years and so many thousands of dollars into is almost over, and I hate that.

I love the job, but I can’t stand the career.

What strikes me over and over with these stories is the immense waste of human potential. We’re looking at people who have tried to do everything right. They got the degree, and they loaded themselves with debt. And those who love what they do — who genuinely serve the public purpose of the university — have little reason, as “rational decision makers,” to keep doing it.

So I would ask the college administrators: How can you live with yourselves? How can you work in a system that produces such outcomes? You call yourselves educators. Are you aware of how you’re really educating people? Sign the contract. Give the teaching assistants and the adjuncts a fair wage for doing the important work they love.

NOTES

[1] This summary is tendentious and unfair to Arrow, who doesn’t believe education is “100% signaling.” That doesn’t mean, however, that our neoliberal-dominated society hasn’t adopted, unconsciously or not, the vulgar version of his theory.

[2] This should in no way be taken as a denigration of the University of Maine as a teaching insitution; it has many dedicated and excellent teachers, despite the miserable and insulting wages and working conditions.

[3] And one important role that old codgers like me can play is to serve as living witnesses that things don’t have to be as they are. The California Master Plan for Higher Education succeeded in the achieving this goal: “[A]nyone from anywhere in California could, if they worked hard enough, get a bachelor’s degree from one of the best universities in the country (and, therefore, in the world), almost free of charge.” Free stuff. Oh noez!!!!!!!

[4] “Yes, I have a double doctorate in Union Busting and Identity Politics Doublethink.”

[5] I know institutions like Harvard are nominally private. Education is, nonetheless, a public good.

[6] The NLRB throwing shade on this point:

NLRB majority ruling adds "[sic]" in a quote from 2004 Bush-era NLRB ruling about "imposition" of bargaining #shade pic.twitter.com/2AY1j9Ezqu

— Josh Eidelson (@josheidelson) August 23, 2016

Is anyone working on automating the work of the administrators? Seems like it would save tons of money and be fairly easy to boot. Rather like Zaphod’s suggestion about replacing Arthur Dent’s brain with an electronic one: “All you would have to do is program it to say ‘What?’ and ‘I don’t understand’ and “Where’s the tea?’ and who would know the difference?”

Or are those jobs sacred due to friend of a friend of a friend, you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours networks?

Ha. The only thing that can’t be automated is teaching — the squillionaire fad for MOOCs died fast — and that’s just what they want to get rid of.

In fact, yes, they can automate administrators. If a college president can leave the college for weeks or months and not have their absence noticed, a forward-thinking administration could just purchase a dummy and have it periodically emit random neoliberal platitudes.

Perhaps the Japanese sex doll manufacturers could branch out.

No no MOOCs didn’t die. They are not seen as the magic panacea that they once were but they are still very much alive and still being coveted by institutions such as Harvard, MIT and Stanford who view them as a way to “scale out” (i.e. cash in on) their brands and to make money at the expense of other institutions.

That said the only people who succeed with them are generally those who already know some of the material. So they fail on education grounds, at least for now, but as I’ve heard the CEO of one MOOC provider once said “Who cares about the pedagogy? We are making money.”

> So they fail on education grounds

Sigh…

Looks like nothing for the adjunct has changed since the 90’s, except that it’s worse now because of student debt. Adjuncts are organizing now, which is good, I suppose, but i doubt it will change anything. There’s no money in the Univ budget for full time positions for all the adjuncts. So what should adjuncts do? Cut their losses? That’s a difficult proposition to contemplate after the financial/psychological investment, but still worth considering. A smart motivated person (who is still fairly young) should be able to develop a different career, even in this shit economy. The benefit for cutting their losses and finding other careers would be twofold: a sustainable career and a “starve the beast” result for the universities. The Unis have to hire teachers; no adjuncts, they starve. I have to say that I would gleefully enjoy seeing that result!

I think there’s money if budgeting is reconfigured. Gut the admistrative layer, and change the business model so you don’t have to build fancy facilities that have nothing to do with educaton. I bet there’s work out there on this (the University of Southern Maine faculty did similar work) but I didn’t find it. That doesn’t mean it’s not there; this was my first foray into this very dense material.

Yes, some budgeting could be reconfigured if the will is there. But what about community colleges? They don’t spend big on buildings or fancy gyms but have relied on adjuncts for decades. It’s all about tax allocations, states cutting budgets for state higher ed. The colleges need to flounder, starved for instructors, before more money would be allocated. Even then. . . some regressive legislators would probably view that situation as a good one.

Presumably collective bargaining could take that into account?

Collective bargaining does not effectively take into account the problem of state budgeting for higher ed. The reason in at least some cases is because the unions themselves are compromised and effectively corrupt: they are overwhelmingly staffed and controlled by tenured faculty, and collude with the neoliberals to exploit adjunct labor in order to maintain their own privileges – a classic “aristocracy of labor”.

E.g. where I live and work, here in NY state, both adjuncts and regular (tenured) faculty are represented by the UUP. But although the UUP for many years has pretended to the model of “industrial unionism” (treating all members as equals), the reality is that the UUP has colluded all along in the 30-odd year construction of this exploitive system.

Why would union officials, dedicated to the rights of labor, choose to be willing participants in the creation of a system of rank exploitation (no pun intended)? The simple answer is because that is where their interests lie. Faced with growing budget shortfalls, the only way the tenured faculty could maintain their social expectations of rising affluence was to consent to the creation and expansion of a two-tiered system. In effect – and this cannot be emphasized enough – the privileges of the tenured faculty – salaries, health care, office space, course and hours selection, sabbaticals, academic freedom, access to grants are just some of these – are heavily subsidized by the exploitation of part-time labor.

I note that you suggested above that in the purging of excess administrative capacity money might be found to ameliorate the class inequities of the neoliberal university. I am skeptical that this is the case, though I agree that top-heavy institutional structures are part of the problem. This is a narrative that has been adopted by union officials as well (with again the UUP as example). But we might ask why this narrative seems to be the “go to” solution for the deeply-rooted (structural) inequities of the neoliberal university – even though, as you noted, no one seems to have produced a study showing exactly where all the money is going, and whether enough could be returned to instructors through evisceration of excess administration. I suspect that one key reason for the popularity of this notion is that it is a congenial one for union officials and tenured faculty to embrace: it absolves them of any agency in the creation of this system, and of any real responsibility for the changing of it – a responsibility that would necessarily include their fair sharing of the burdens of neoliberalization, which they have so far managed to ‘externalize’ to the adjuncts.

As long as the class divide persists within the neoliberal university, it will be impossible to effectively stem the tide of change: proletarianization of higher (and primary) education will happen just as it did historically in other trades. For the privileged elites of the aristocracy of labor – the diminishing ranks of tenured faculty – will continue to externalize the heavier costs of neoliberalization until the thing is a fait accompli, and a return to direct instruction in the face-to-face classroom will be as inconceivable as having one’s shoes made by the local cobbler.

Here’s an anecdote from my local community college: the long-time college Librarian (Chief) left this most stimulating position to become an assistant Dean (paper pushing). I came across him on campus recently and he explained he did it for the money.

That is the measure of higher education in California.

Cheers.

I wonder how many adjuncts and University TAs (current and to be) would continue after a quick read of this Wiki page on what has historically been called the “sunk costs fallacy” by economists:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escalation_of_commitment

In a liberal-arts program at an Ivy League university in 1974, after a year’s research assistantship and a year’s teaching assistantship, I passed PhD prelims. Then the university cut off funding–the department perhaps thinking I’d fall for the sunk-cost fallacy (although I didn’t know that term at the time; the thought of incurring any more debt on top of what I owed for my undergraduate degree terrifed me). So I didn’t register for the next term. In a one-year visiting professorship, seeing other ABDs and PhDs struggle for one-year gigs in disgusting locations, I forsaw what today’s tenure-pursuers and adjuncts are suffering, and bailed out of academia.

After a few crap jobs in the financial industry, I ended up doing ok at a New York money-center bank and repaid my undergraduate debt in 3 years. After ~30 years in IT in various cities and companies, living frugally, it seems I will after all (financially) survive into my 80s, if fate allows. Even though I may have sold out as a corporate minion, I am grateful that I escaped academic poverty.

Thank you, early 70s.

This is an excellent summary of the current state of affairs. However, I have to quibble with one point: The layers of administration are not primarily the top 10%, but rather the majority are individuals earning in the 30-70k/year range. The numbers within these administrative layers are daunting, and they have better job security and benefits than most everyone else in universities. The majority also strongly support candidates like Clinton.

Thanks for both points.

`Administration’ is a broad brush. If one uses it to include pink-collar jobs (30K) and experienced departmental administrators (40-70K) who are essential to the running of a university, that muddies the waters. When people talk about administrative bloat, they usually mean positions like the Assistant Associate Vice Provost for International Engagement (I’m just riffing on the Assistant Vice-Provost for the Global Network University of New York University) that are far more highly paid. Although how far depends on the position and the school.

Yup. I’ve adjuncted from 2004-present, though I’ve had a full-time non-academic job since Jan of 2015, with a decent salary, benefits and union membership. I did one stint as a Visiting Professor as well. It’s all a scam unless you win the lottery that is academia and wind up with a tenure-track gig, though most of those positions go to people with Ivy League (or near-Ivy) grad degrees. I typically made between $16-$18k a year even teaching 3-4 gigs a semester. I burned out after nearly a decade at it, and as boring as an office job is, at least I have money in the bank and health care.

The Neoliberal Method of Crapification in 3 Easy Steps

1. Take out lots of debt

2. Spend it on useless garbage contrary to your organization’s purpose

3. Now that all available money is going to interest payments, use lack of money as an excuse to scourge workers and destroy the quality of whatever you used to produce

University crapification example:

Take out lots of debt. Spend it on marble floors, athletic buildings, and million-dollar admin salaries. Convert teaching positions to temporary adjunct workers.

Hospital crapification example:

Take out lots of debt. Spend it on marble floors, acquiring competitors, and million-dollar admin salaries. Rent nurses and janitors through three different layers of contractors; send indigent patients’ bills to collections.

Nation-state crapification example:

Take out lots of debt even though under MMT you have no need to. Spend it on wars and tax cuts for rich people. Cut spending on infrastructure, pensions, and education.

Private corporation crapification corporation example:

Take out lots of debt. Use it to acquire a company. Put the debt on their books, lay off half their workers, hire sketchy contractors and offshore workers in their place. Don’t forget your million-dollar salary!

Worth remembering: Not even STEM grads can be assured employment, so what chance do us liberal art-ers have?

Mao Zedong loved STEM grads, too. He hated and discouraged liberal arts grads.

STEM is training. Liberal arts is education.

Can’t have too many in the population thinking, making connections, etc. It’s just too hard to manage.

STEM is training. Liberal arts is education.

Funny. Or not. The most die-hard Hilbots I know are all in the humanities.

does your definition of the humanities include the social sciences?

Not so funny. The humanities people I know refuse to think outside their box which means lack of understanding and therefore empathy for those outside their class. Name calling and condescension result. As a liberal humanities person, I recognized my own prejudices in the 80s and began to stretch my liberal political understanding by listening to conservatives. Painful, yes. Lots of winching and scowling on my part, but I did learn a few things. People with different viewpoints are not stupid. That exercise served me well. I have continued to extend my intellect by reading in the alternative weblogs and foreign press. I still find that my humanities friends are resistant to educating themselves outside their narrow preconceptions. They would never entertain reading anything at Russia Today! The stupidest people I know are my humanities educated liberal friends. And sorry to say that some are teachers!

And that’s 180° the reverse of what the humanities should be. What the heck happened there?

A fear that you’ll become unhappy if you allow yourself to realize what state you/we are in?

I mean, the thing that puzzles me most about “professionals” is how dismissive they become as soon as you start pointing out that there are alternatives to the things that are acceptable among “adults”; presumably because they live by Jon Stewart’s infantilizing motto that if “liberals” and “conservatives” are both unhappy (and you’ve “triangulated/compromised”), the outcome you have is the best attainable.

While some STEM is indeed training (and there is NOTHING per se wrong with job training, but it is mostly meant mostly to train for employment), STEM as a whole is NOT training.

The absurdity of thinking a physics PhD is training is well … it kind of refutes itself. But even say CS, that’s NOT training. Liberal arts majors can say courses they haven’t taken are mere training but they simply don’t know what they are talking about. Look I’m not claiming STEM majors are experts on pontificating about getting a graduate degree in liberal arts either, I’m just saying I think the whole conversation proceeds out of utter ignorance. It’s just the mindless repeating of clichés.

Now if people are taking a college workload to get a job, which many are, and it’s understandable enough, then many people will fake their way through it, more interesting in the prize than the academics, and that’s the truth. But whether or not people fake their way through it doesn’t really say much about the subject itself.

STEM is training. Liberal arts is education.

Perhaps you didn’t mean this literally; but, if so, you must either have a very constrained notion of STEM, or an incomplete understanding of science and mathematics.

Or perhaps you have an imperfect understanding of liberal arts? It used to be taken for granted in liberal arts colleges that people would take a certain amount of math and science, because your education was not sufficient without them. The problem I have with STEM is that it does not reciprocate by acknowledging the necessity of education in literature, languages, history, geography, and the arts.

So-called “parasite” reporting in. If only it were so simple that people like myself were simply carving off our piece and being supremely evil. Let’s talk about a few departments at my current university:

Development:

Massive office. The Development office’s job is to raise funds from alumni, corporations, foundations, and, depending on structure of the university, the federal government through various grants for the institution.

Financial Aid:

Also a massive office. The financial aid office’s job is to make sure that students are paying bills and sorting out the incredible constellation of grants and loans that surround student payments.

Admissions:

Massive office. They admit students, but also play a huge role in sorting out financial aid. The student going to school in 2016 is savvy and knows they can horse trade in grants to get the best deal. Extremely competitive for students.

If you’re seeing a pattern, you’re probably seeing that most of a university admin’s structure is devoted to seeking out funds from all kinds of sources: students, public, private, and from the alumni and others.

Is this good? Well, if I was in a wholly federally funded education system, I’d probably have problems with that too. Some argue it creates institutional sovereignty. In any case, it’s common knowledge that state governments don’t fund state universities to the degree they used to. The federal government funds nothing but its loan apparatus, with a diminishing amount going to things like basic research.

So, yes, a school hires people to make money. These IHE’s are no longer there for the public good, because they aren’t funded by the public. When they are funded by the public, it’s all done through arcane granting processes through DofEd, research foundations, and the many other government agencies. For the rest, there’s alumni and corporations to foot the bill. Colleges and Universities are expected to be self-sufficient in their funding, from the land grants to the SLACs. I’m sure there are plenty of exceptions to the idea here, where there really are parasites around, but the fact of the matter is that these colleges and universities don’t exactly run for free, not with the many unfunded mandates out there.

But hey, I’m just one of Lambert’s parasites, one of what, millions of people? who staff the non profits called higher education institutions.

You don’t see, like, kinda a pattern in “massive offices”?

To answer your question: Yes, I think millions of people are engaging in a useless activity that’s destroying many lives (though not their own) and is bad in every way, for the culture, and the country. And there’s a lot of that going around. There were a lot of people involved in robosigning, too. Didn’t your mom tell you that “Just because a lot of people are doing it doesn’t make it right”?

Just like Health care Billing.

I’d estimate 25% of the working population are doing noting productive.

25% non productive is probably right, most of that would be in the public sector. The private sector can’t afford non productivity and expect to stay in business because of competitive pressures to evolve or go out of business. That’s where the merit of capitalism shines, I’ve seen first hand layers of non productive upper management bloat cleaned out.

Lambert: you might also consider seeking out the work of Slaughter & Rhoades (some listed here: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=TZBSQ18AAAAJ&hl=en ); I read one of their books (I think it was Academic Capitalism) about 8y ago, which I found quite interesting, though I don’t recall it touching on stuff like those mentioned above (e.g. increase in overhead on the side of student admissions/loans due to skyrocketing tuition being a feature of sorts). OTOH, I may simply have forgotten, as I wasn’t quite awake to the cultural significance of the growth of bureaucracy (-> The Utopia of Rules).

Didn’t I just identify the pattern and give you the examples? I don’t really understand your response. There’s a heck of a lot more there than, “lots of people are doing it”.

Fortunately I got a better response downthread. You avoided the public versus private issue of funding altogether. You can’t even begin to look at state colleges and their activities without looking at the pullback in funding.

If what you’re arguing for is a massive rethinking of public education, along the lines of diverting military spending to the cause or a similar scheme, then I don’t think you’ll find many scoffers here. But these lines are hard to decipher: “Well, if I was in a wholly federally funded education system, I’d probably have problems with that too. Some argue it creates institutional sovereignty.” Presumably this federal kind of system wouldn’t preclude private universities, nor would it negate constitutional guarantees to academic freedom (speech, association, and the like). So we’re left with what “institutional sovereignty” might mean.

As it is now, as Lambert’s post argues, we live under another form of institutional sovereignty — namely, the neoliberal corporate one. And this has actually created the precariat — grad students, adjuncts, and frankly, a lot of students who never graduate (but who took on debt) and a lot of graduated students who took on debt (and who we make fun of daily on MSNBC, Twitter, and late night shows — “basement dwellers”.) Either we start to nip this in the bud, or we settle for indebted workers filling up massive offices in corporate universities strangling actual education to pay for admin.

It shouldn’t surprise us that as it is now, a lot of PhDs end up accepting jobs in admin. Even with published books and teaching experience. This isn’t the solution, this fact elucidates the problem.

Absolutely, I think you’re completely right. And we need to nip it in the bud immediately.

However there are clear reasons for why we got here and Lambert doesn’t really touch on them. Was talking to a friend in the research game at an R1 yesterday. He mentioned that his department spent gobs of money on grantwriters just to continue the research funding for his projects. And that grant writers were the main reason they got their grants by the end.

The federal government has pulled way back on basic research funding, for instance at NIH, where a first time proposal has a 0-1% hit rate, whereas in China, their national research fund has a 25% hit rate.

Universities have turned to neoliberal corporatism because the public nature of previous funding has all but vanished. I’m not saying it’s right. But the post above seems to be flabbergasted that universities are now private institutions. Duh! They aren’t public because they have now taken in the bureaucratic elements of the organizations that they used to rely on support from (state and fed government, the two big ones). That’s just a natural reaction to disappearing funding. We can call it useless, but it actually has its uses, namely, keeping the apparatus alive.

Actually, the funding disappeared because they started experimenting with a competitive grant system, plus demanding that researchers started attracting outside (corporate) funding, back in the ’70s iirc. (Described by Slaughter in Academic Capitalism.) Then once some researchers managed to find some funding, and the world didn’t end, this very fact was used as an argument as to why further cuts were unproblematic. The other issue (competitive grant funding) probably had something to do with the explosive growth of academia thanks to the GI bill etc. making it seem logical to say “we can’t let the university grow even further, so we’re going to introduce competition so that we aren’t giving bad researchers money, etc.” + whining about how tenure encourages mediocrity, so we need expert evaluators who check the quality of research proposals, or whatever. There of course were other reasons, but these are among the more subtle/insidious ones.

I’m definitely keenly aware of the rise of competition in grant funding (have a lot of experience there), but in addition, the major foundations and institutes aren’t exactly indexed to inflation or the needs of the day. It’s all Congress.

And the fact of the matter is, also, that everything else is competitive as well. Student grants have a huge application process to weed out the unworthy. Colleges and universities have to offer competitive grant opportunities for students or they can’t reach enrollment.

The more I thought about this, the more I realized it’s now the government generating loans to fund positions to ask the government for money (specifically in development and financial aid). Then the government creates unfunded mandates and uses the loan money to pay for them as well (state university had a “healthy masculinity coordinator” to fulfill their title IX compliance requirements). All the while, none of the loans can be discharged in bankruptcy.

Thanks for your post. I think we can have a constructive conversation about this.

Oh, certainly. Like I said above, I hadn’t really thought about the student loans/applications/admissions side of the story, yet, but that’s just as much a part of the process as everything else, as is its metastasis. (Though an egalitarian living in NL, the very notion of unaffordable tuition fees, that only some get waived when they are deemed to “deserve” it, as well as govt loans @~8% — dutch student loans are tied to inflation, and the interest rate on mine currently is 0.05%, reset every 5y — always revolted me, precisely because of the “competitive”/ social darwinist element. But it’s hard to get a feel for how many people are caught in that system from this distance.)

Many, many people, unfortunately. Same researcher I talked to has still has outstanding student loans.

If you go to any community college in the country during August and September, you’ll see those financial aid people people earning their keep. They are saints for the things they have to put up with, both from the government and from the parents.

Far from robosigning. But I don’t expect Lambert has been to a community college to watch parasites on move in day.

STEM training is just the latest NeoLiberal codpiece to hide the teeth of its groin ferret.

Training in engineering no more makes paying jobs in engineering than well disciplined critical thought makes paying slots for itself in the Liberal Arts.

“Elite overproduction” is NeoLiberalism’s excuse for its degradation of everything that supports it. It is in fact opportunity extermination by the powerful fearful for their positions or pathological in their hatred of everyone they do not know and control, afraid all those are soulless just like themselves.

There’s another layer: the “invisible hand” of Governing Boards. Here’s a summation of the famous UVA public U example: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/09/16/magazine/teresa-sullivan-uva-ouster.html?_r=0

(Be sure to see the nice flow chart of all the players.) This also was about MOOCs etc.

But it’s often worse in the private U world. Over 80% of the my university’s board are businessmen (sic). The rest are a hodge-podge of clergy, retired educators etc. Until recently, all were chosen by the president. Some of these members (the most vocal) are outspoken libertarians. It influences the whole culture, starting with the pre-eminence of the Business School (easily the most beautiful, tech dense, spacious classroom building on campus). Who gets building contracts on campus, etc.

Do I know any faculty voting for Trump? Of course not. He’s a “buffoonish businessman!”

I always say: “Who do you think rules us here at beloved U?” Regional tin-pot versions of the Donald.

Better stop now, the blood pressure is rising.

I remember the UVa debacle, but I’d forgotten “strategic dynamism.” Dear Lord. Here’s the diagram:

“Why be good when there is outstanding to be had?” — Paul Tudor Jones

Ah, the bedeviling unconscious.

In many states, salary and wage information for all public university employees – as for all state employees – is required public disclosure. After reading your article earlier today, I found a cursory review of this info to be enlightening.

An under-reported aspect of university administration in this era has been the aggressive use of debt to fund building construction at many public universities. Not to diminish the value of athletics, but a state university with which I am familiar incurred about $140 million in bond debt to fund expansion of the football stadium and for a new football operations building. Like most universities, this university’s Athletic Department has reported a net operating deficit of many millions of dollars since at least 2012, including a reported net deficit of over $13 million for the last fiscal year. This despite bowl game revenues, a television contract, and an additional fee that is being assessed all students at the beginning of each term.

The teaching of competition, the addiction to the thrill of victory, and the arrogance of the winner are cultural tenets that some consider worth a $13 million outlay to preserve.

> Not to diminish the value of athletics

Well, I do have priors on Big Football. Letting the players unionize would be a start, but I think spinning all the Big Football programs off into their own league would be cleaner. They could license the logos.

And on debt, that’s Rezlez’s first step, isn’t it?

This post and its associated comments are depressing. How can our teachers be so poorly paid? How can we have too many well-educated people? The comments echo some sort of long time combat between the Muses. I feel as if our society is working hard and fast toward some kind of collapse. What country is this where we work so hard at destroying our culture and the quality of our lives?

Another aspect of this is the offloading of training for jobs by the employers. In the long ago, employers would pay lower wages as compensation for providing hands on training for a task that would eventually make the employer a profit. Now, the employee is expected to finance his or her own training and accept the lower wage at the same time.

Roughly, the society has entered an “inversion of values” phase. The provision of socially useful skills has been financialized to the extent that said skills are becoming harder and harder to find. With the lowering of standards and skill sets this financialization brings about, the society decays to the point where the financial segment also decays; a result of its own actions. This is not a ‘chicken and egg’ situation. There is a clear process involved with a defined order. To have the economy work smoothly, skills must be taught that enable production, that then is utilized for the financial field. By redefining the “economy” as being mainly the financial realm, the ‘movers and shakers’ have shot themselves in the foot.

On the positive side, the unionization efforts are truly happening. In my sizable Midwestern city, 3 major universities had successful unionization campaigns for adjuncts. All were in 2015-16.

That’s good news.

Define “successful” please.

From my understanding (the major newspaper here) all 3 have formed unions and 2 are in contract negotiations. At the top rated university, which receives the most attention, they won a new contract. The union went through 20+ bargaining sessions with a final threat by the adjuncts to walk out of class. According to the adjunct leaders interviewed, they ended up with basically what they wanted — significant pay increases and some benefits. This also happens to be the wealthiest university. As for the other 2, their unionization was this past Spring.

The reports are that all joined SEIU. So I googled around and found this. I imagine success is measured by similar metrics:

http://seiufacultyforward.org/seiu-contract-highlights-the-union-difference/

Great news. Job actions – or the threat of them – is the only way to get results.

Unfortunately, it takes a very very very long time to get people to realize that.

Universities count on the fresh supply of new dupes, I mean, excellent cheap labor, it cranks out every year in grad programs.

While public-sector TAs can organize anywhere, those organizations, like other public-sector associations, are prohibited from collective bargaining in about half of the states.

Thanks for the clarification.

“In other words, half the academic precariat, makes less than a high-end Walmart cashier or Pharmacy Technician, and a Walmart Sales Asssociate, at $25K, is in striking distance. ”

60 years ago Kenneth Rexroth made the point that a lot of the greatest musicians of that time (he was thinking of NYC avant-garde) were financially worse off than cashiers at department stores. Academics have just joined them. (Rexroth was careful to point out that he was not saying that clerks were overpaid).

Thank you for an excellent article on the destruction of higher education. I especially like the image of schools being injected with neo-liberal venom. I lived the life of an adjunct for 28 years, teaching law, business ethics and business communication, first at a community college and later at the Univ. of Washington business school. In the 1980s and 90s, adjuncts were forced to filed class-action lawsuits to get health insurance and the right to pay into TIAA-CREF retirement system. My pay went up a bit at the UW, but academic apartheid was still the rule. We adjuncts taught the majority of undergrad classes so the overpaid, under-worked tenure-track faculty could concentrate on the doctoral students and especially the executive MBA program. We were paid a fraction of the full-timers, shared tiny offices and had no job security.

In 2006, the Washington Legislature allocated raises for all UW faculty, but the University refused to pay us. The AAUP, which was supposed to represent all faculty, sued on behalf of the tenure-track, cutting out the adjuncts altogether, and got a big settlement. Every teachers’ union I’ve ever belonged to has used my dues and its clout to work against my interests.

I filed a class-action suit against the UW on behalf of adjuncts. We settled and received our back pay and raises. However, the accountants who had recently taken over the business school forced me and many other adjuncts out of our jobs. At 56, my career was over. The bean-counters roused the undergraduate business school rabble to despise anything that wasn’t quantifiable, including business ethics, business writing and law. The atmosphere in that school had become intolerable, so perhaps it was just as well that I got pushed out.

Higher education has turned into just another neo-liberal mining operation: to suck money from students, adjunct faculty, taxpayers, cities burdened with large research university and taxpayers. Like a cancer, the UW is destroying Northeast Seattle with its constant growth, with sports palaces, taller buildings to house administrators, increased tuition, higher rents, destruction of small businesses. The UW even has its own dedicated lobbyist, a former City Council member who is helping to turn NE Seattle into another South Lake Union (home of Amazon.)

My dream in high school was to be a university professor. I was always an excellent student in all subjects and even made it into my dream college (an elite liberal arts school). I got a very good education but I was only a B+ student because I had attention span issues. While I could focus in high school all day (and there wasn’t all that much homework), college was nothing but reading hundreds and hundreds of pages of really dense material (mostly social science classes). I could never focus on it for more than an hour or so and then my mind would start wandering. Of course I did really well with the material I did read, and kicked ass in a few classes while I was there (the ones where I did almost all of the reading), but in the rest, I’d impress the professor for a while, and then they’d find out that I wasn’t doing a lot of the reading and I’d end up with a B.

I didn’t like my experience being locked away in the ivory tower and I decided against even attempting to go to grad school. I would have been able to get one very good letter of rec but the rest of the professors would have only said that I was smart but never stood out. With mediocre grades and only one letter of rec, there’s no way you can get into a top graduate program. Sure, I could have gone to my local state graduate school, and then what? I’d have no job opportunities. My best case scenario would be moving around the country to various college towns full of students primarily there to socialize. I’d spend 60-70 hours a week on my job, get paid hardly anything, and have a really unfulfilling social life. Finding a wife willing to relocate to these places every year would be a challenge, too.

While I got a fantastic education (could have learned more though if I’d done a better job with my reading), my diploma didn’t mean anything more than the one I would have received for free from my mediocre local university. Sure, my school did have a lot of opportunities and even connections for the top students, but I was an average student there, so none of that really benefited me.

My high school just had its ten year reunion and two of my classmates have already become professors, one in psychology and the other in finance. Neither was considered one of the ‘smart kids’ at the school, and one of them didn’t even have that tough of a schedule.

I’m sure glad I didn’t end up like one of the horror stories you hear but what is it about my two high school classmates? What did they do differently? What did they have that I didn’t? And if it’s so incredibly competitive to be a professor (I was told by many at my college that if you didn’t get into the top five programs or so in your subject, it wasn’t even worth going to grad school), how did they go to mediocre grad schools and get professorships right away? What did they do differently? What do they have that I don’t?

This is the terrible question that our neoliberal faux-meritocratic order forces people to ask themselves as they struggle to sleep at three in the morning. The truth is, they don’t have anything important that you don’t. They might have had astonishing luck, or a keen sense of which boots would best repay assiduous licking.

Academia is no more meritocratic than any other world. There is no true meritocracy, only more and less powerful people. Occasionally you will see powerful people afford a comfortable space from which someone, like Noam Chomsky, is allowed to rail against them. Centuries ago, people with comfortable Church incomes, given to them by wealthy prelates, often preached against the greed and hypocrisy of the bishops.

I fear that the arrogance and smug insularity of our ruling classes will lead to destroying the very habitability of our planet. They will not stop fracking, strip-mining, etc., until there is not one drop of potable water left to drink. Today there is no more urgent cause than recreating a bountiful commons. We need places of refuge from the harsh battlefields of neoliberal competition. Places where people are free to express themselves, without fear of losing their livelihood.

Our ruling elites have killed all the geese that laid their golden eggs. There is absolutely no reason why we shouldn’t have marvelously rich cultural institutions open to all. Did you know that the Met literally has more money than it knows what to do with? Yet they ask an outrageously high “suggested donation” for admittance! https://news.artnet.com/art-world/metropolitan-museum-changes-admissions-wording-436037

I suggest that we reclaim our commons, in the wilderness, in the city, on the ocean, in the air. We are many, they are few. After hiring strikebreakers, 19th Century plutocrat Jay Gould said “I can hire one-half of the working class to kill the other half.” That was wrong then, and it’s wrong today. No amount of state or private violence will manage to preserve the obscene hoards of the kleptocrats– once people put aside their differences and unite in determination to retake the commons.

Fantastic post!