By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

At a recent meeting on our ongoing fight against “the landfill” — situated[1] on a high ground near the Penobscot, owned by the state, but privately operated, hence rapidly being filled up by out-of-state trash to the profit of the operator, and therefore to be expanded — I was impressed by the thinking of one young environmental scientist from the University of Maine. For context, Maine solid waste policy should be governed by what is called “The Solid Waste Hierarchy,” which is embodied in statute:

Title 38: WATERS AND NAVIGATION

Chapter 24: SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT AND RECYCLING HEADING: PL 1995, C. 465, PT. A, §26 (RPR)

Subchapter 1: GENERAL PROVISIONS HEADING: PL 1995, C. 465, PT. A, §27 (RPR)

§2101. Solid waste management hierarchy

1. Priorities.

It is the policy of the State to plan for and implement an integrated approach to solid waste management for solid waste generated in this State and solid waste imported into this State, which must be based on the following order of priority:

A. Reduction of waste generated at the source, including both amount and toxicity of the waste; [1989, c. 585, Pt. A, §7 (NEW).]

B. Reuse of waste; [1989, c. 585, Pt. A, §7 (NEW).]

C. Recycling of waste; [1989, c. 585, Pt. A, §7 (NEW).]

D. Composting of biodegradable waste; [1989, c. 585, Pt. A, §7 (NEW).]

E. Waste processing that reduces the volume of waste needing land disposal, including incineration; and [2007, c. 583, §7 (AMD).]

F. Land disposal of waste. [1989, c. 585, Pt. A, §7 (NEW).]

It is the policy of the State to use the order of priority in this subsection as a guiding principle in making decisions related to solid waste management.

It will come as no shock to readers when I say that the state, operating seemingly under the strictures of Matthew 20:16, has inverted the heirarchy: “Land disposal of waste” (that is, landfills) is the first priority (because ka-ching[2]), incineration is being phased out, another business arm of the landfill operator has systematically destroyed local composters, and another business arm of the operator is attempting to destroy local recycling. (In Maine’s case, “reduction of waste generated at source” would mean controlling out-of-state sources; difficult to do under the Commerce Clause, but possible for a state-owned landfill, did we but try.)

Why? Because markets. Collecting a fee for dumping ginormous amounts of out-of-state trash into a hole in the ground is more profitable — in dollar terms — than any of the alternatives.[3]

This is, of course, insane, by any other measure than profit for the operator. The landfill is situated on high ground near tributaries with only a short distance to run into the Penobsot. When the landfill liner fails — as all landfill liners ultimately do — toxic leachate will end up in the Penobscot. Maine doesn’t have a lot going for it, economically, but — paging Michael Burry — increasingly precious clean water is one such thing. (The Penobscot River Restoration Project has made immense progress cleaning up the river from all the damage done by the industrial pulses of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.)

Profits, however, are quantifiable: Everybody knows what they are and what (ka-ching) to do with them. “The policy of the State,” however, is not quantifiable, and in practice its determination is at the mercy of the army of lawyers and lobbyists deployed by the operator. But what if there were an accounting method other than dollars that made the real costs of the landfill — in this case, the endangerment of the entire Penobscot river basin downstream from the landfill — visible? That would shift the terrain of the regulatory battle in favor of the defenders of the river basin, both inside the regulatory process, and outside it, in the public eye.

As it turns out, there is such an accounting method, and that’s what I liked about the young environmental scientist’s thinking. The key concept is “emergy” — with an “m” — and the methodology and systems thinking behind it was developed by Howard T. Odum of the University of Florida, “the father of systems ecology.” My takeaway from the meeting, therefore, was that policies implementing the Maine Solid Waste hierarchy should be justified using emergy as the unit of account, and not dollars. Happily, if this approach were to be taken, the landfill expansion would not be approved.

Caveat, even moreso than usual: This is my first foray into environmental accounting, which is a vast (and heavily contested) field. My purpose in writing this post — besides doing my little bit to cripple the landfill — is to introduce the emergy concept, and hopefully encourage readers more expert than I (like, all of you) to expand on and critique it, or even offer superior alternatives. To an actual environmental scientist, therefore, this post will be distressingly simplistic. I will introduce the emergy concept, present a worked example, make one of the more obvious critiques, and conclude.

Concept

Here’s how Odum defines emergy on his site (and I’ll give a less forbidding restatement following). First, he introduces the idea that flows and forms of energy are hiearchical:

Self organization develops a network of energy transformations in a series. … Since energy flows are converging at each step to make fewer flows of energy at the next, it is an energy hierarchy. … Examples are the energy chains in organisms, ecosystems, economies, earth processes, and the stars.

Work is defined here as the available energy degraded in an energy transformation. Since many joules of available energy on the left[-hand, input side of a transformation] are required to make the successive transformations to form a few joules of available energy on the right[-hand, output side of a transformation], it is quite invalid to use joules of one kind of energy as equivalent to joules of another for purposes of evaluating contributions. However, we can express each kind of available energy in units of one kind of available energy.

From the perspective of a physicist, I suppose, energy is energy; everything is a joule. Intuitively, however, as Odum points out, kinds of energy are not interchangeable: To burn coal instead of oil, for example, I would have to expend energy to convert my boiler, I’d have to make sure there was actually a functioning system for delivering coal to my house, and so on; the transformation is not free of “friction.” Odum urges that “energy” cannot provide an account of this transform; “emergy” can. He goes on:

Emergy (spelled with an “m”) evaluates the work previously done to make a product or service. Emergy is a measure of energy used in the past and thus is different from a measure of energy now. The unit of emergy (past available energy use) is the emjoule to distinguish it from joules used for available energy remaining now.

There is a different kind of emergy for each kind of available energy. For example: solar emergy is in units of solar emjoules, coal emergy in units of coal emjoules, and electrical emergy in units of electrical emjoules. There is no emergy in degraded energy (energy without availability to do work). Like energy, emergy is measured in relation to a reference level. In most applications we have expressed everything in units of solar emergy.

Sounds complex. Then again, natural systems are complex. Here’s a friendlier definition:

Emergy is an expression of all the energy used in the work processes that generate a product or service in units of one type of energy. The unit of emergy is the emjoule, a unit referring to the available energy of one kind consumed in transformations. Emergy accounts for different forms of energy and resources (e.g. sunlight, water, fossil fuels, minerals, etc.) Each form is generated by transformation processes in nature and each has different ability to support work in natural and human dominated systems. The recognition of these differences in quality is a key concept of the emergy methodology.

And an even friendlier exposition:

Odum identified the work of biosphere, driven by solar energy, as the source of resources and environmental services, and provided a

common measure for them (solar emergy). Odum suggested emergy to be the basis for value and sustainability assessments

That is, if we were able to give an accounting, quantitatively in emjoules, of the contribution of the Penobscot River basin to the state of Maine, versus the emjoules contributed by the landfill, we wouldn’t be thinking about expanding the landfill for a moment.

Example

Just to show that emergy isn’t an airy-fairy, hippie-dippy concept, here’s an example of emergy accounting performed for the United States Forest Service:

Brown and Campbell (2007) used emergy analysis to estimate the value of the natural capital and environmental services of the nine regions of the U.S. Forest Service (USFS). They evaluated the energy, material and service flows that drove the USFS system, and they also evaluated the system’s assets (environmental, economic, geological and cultural). They analyzed two forests, the Osceola and the Deschutes, to apply the methodology at a smaller scale. The authors chose to express the results in emjoules and in monetary-equivalent emdollars to yield comparable results.

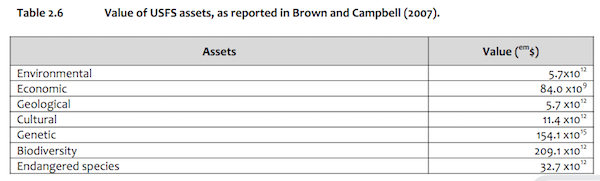

The authors calculated the annual emergy driving the USFS in 2005 at em $42.7 billion, most of which consisted of renewable environmental flows. Exports from USFS lands (described as “environmental subsidies to the U.S. economy”) added up to em $263.7 billion. Forty per cent of the export value came from clean water, and 37 per cent from fossil fuels and minerals. Wildlife, wood biomass, hydroelectric power and a range of smaller environmental products accounted for the remaining 23 per cent. The authors calculated environmental assets in different groupings: environmental, economic, geological and cultural assets. They also calculated the emdollar value of the genetic resources, biodiversity and endangered species on USFS lands (see Table 2.6).

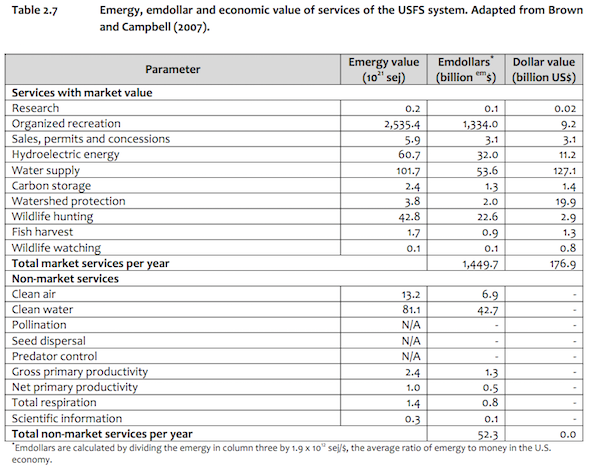

The authors compared the market price of environmental services and natural capital with the emdollar equivalents, though most of the environmental services and natural capital do not have market values (see Table 2.7 for emdollar and dollar values of environmental services).They found the emdollar values they calculated for the environmental services were approximately 8.2 times the market value of the services. They calculated the emdollar value of environmental services without market values to be em $52.3 billion, and they found the em dollar value for natural capital was approximately 2.5 times its market value. Natural capital without market values added up to more than em $2.8×1018. This value was largely due to the value of geological formations.

Here is Table 2.6:

And here is Table 2.7:

As per the caveat above, I can’t do much more than say “Yeah, that seems sensible!” But intuitively, taking the value of geological formations into account makes a lot of sense, and I bet it would make a lot of sense to those fighting another form of extraction from powerless local economies: Mountaintop removal. One of the putative justifications floated for the (hopefully) defeated East-West Highway in Maine was a gold mine (literally) up in the unorganized territories. A mining operation in the Penobscot’s watershed, upstream of everything. What could go wrong?

Critiques

Readers will already have spotted one weak point in the emergy approach. How are emjoules to be made commensurable across kinds of energy? That takes work. From the Proceedings of the Sixth Emergy Conference at the University of Florida:

The application of the emergy method needs a large and reliable database of conversion factors so-called Emergy Intensities or Unit Emergy Values (UEVs), used to convert the input flows (energy, matter, money, labor and information) into flows of emergy driving a process.

Lack of a suitable and constantly updated database undermines the evaluation process and weakens any calculated performance indicators.

This doesn’t prevent emergy accounting from being used for individual systems like forests or landfills; but it would be nice if the conversion factors didn’t have to be developed piecemeal on a project basis. In a perfect world, the conversion factors would be as available and simple to use as any table that engineers use; or the building code.

Of course, a political economy based on endless capital accumulation is unlikely to optimize for the creation of such a database; we prefer to pour our trillions into bright shiny bezzles like Uber, or self-driving cars.

More centrally, I’m leery of universal units of measure. Odum’s approach — the necessity of a “reference level” — reminds me very much of Marx’s labor theory of value, which gave an account of what made commodities commensurable, hence exchangeable, and labor power turned out to be, in practice, unobservable. The fact that I’m leery of something, of course, doesn’t make that something wrong, so I welcome reader commentary on this point.

Conclusions

The young scientist also had — and who among us does not? — an agenda. The permit for the landfill expansion that we are contesting says explicitly that projections of landfill capacity depend on economic growth (or “groaf,” as we say), and that as the Maine economy recovers (as if), landfill capacity will need to increase. So, they asked, given that there’s a direct relation between growth and the landfill, doesn’t growth have to halt? The emergy methodology provides an account for why that should be true.

NOTES

[1] Thanks to corrupt Democrats who to this day have refused to look in the mirror for the landfill debacle.

[2] Not only for the private operator of the landfill, but for a small army of lawyers in Portland, and another small army of lobbyists in Augusta. In a nice touch, this army are billing the state, i.e., me, for its very expensive hours, since the operator is formally the agent of the great State of Maine. I bet if the landfill were sited on Cape Elizabeth, state policy would be very different!

[3] For the operator. Maine governments get a cut of the tipping fees, but most of the profit extracted goes out-of-state.

This is a fascinating concept. My question is could this same concept also be applied say to repurposing? For instance, the salvage and rescue of construction materials such as doors and windows, wood flooring, etc.

I believe it could. Place the door (or whatever) within an energy flow…

Lambert, great to see someone refer to Odum, and I say that even before having read your post. Just wanted to remark that dieoff.com (or .org) is not Odum’s site, it belongs to Jay Hanson, and has a fantastic collection of articles. I never learned more anywhere else in the world. Jay stopped adding to it around 1998(?!) There’s an Emergy accounting PDF by Odum at http://www.dieoff.com/page232.pdf. An overview of all articles is at http://www.dieoff.com/page1.htm. Note: Jay is not an optimistic camper when it comes to humanity.

The “dieoff.com” (love the URL) page I linked to has the heading:

But I’m glad to hear that you don’t find Odum problematic.

A couple of decades ago I did research on environmental pricing methods – I thought I’d seen all the various methods, but emergy is a new one to me but it sounds fascinating and interesting. I don’t have time right now to follow up the links to explore further, but my first thought is that it may well hit the same basic problem most such methods have, which is the issue of commensurability, i.e. the difficulty of assessing different ‘values’ in one unit of measurement.

Emergy is actually not new for people working in or familiar with ecological economics. The trouble is the latter tends to more harbour scientists interested in economics whereas environmental economists tend to be the reverse and the two dont talk much and most come from different intellectual silos.

There are some exceptions though. Try looking up Herman Daly one of the other ecological economics godfathers who started as an economist.

he explained his perspective in DALY, H. 2015. Essays against growthism. World Economic Association.

on a side note, i did not guess this correctly http://www.businessinsider.com/state-closest-to-africa-2016-7

Thanks For the Workup Lambert (on my radar)

From the perspective of a physicist, I suppose, energy is energy

The concepts of entropy and efficiency are useful in defining the “quality” of different types of energy. This is a very interesting post and I will try and read it more thoroughly and leave some more useful feedback sometime in the next few days. I have done some cursory “cradle to grave” carbon equivalent analysis of some production chains during my engineering studies and my impression at the time was that those kind of methods are as good as the assumptions they are based on. Unfortunately, the ideas that constitute what could be perceived as a sensible and measured approach to the environmental challenges we face, are too often lost in the turbulence (energy efficiency joke) of reckless capitalism in the service of the greed of shitty people.

We need to slow down and start making good decisions, but I know readers here know this already.

I just thought I’d mention that I think pretty much everything that needs to be said on this issue has been said. Steve H. knows what he is talking about. In the final analysis, these types of quantification schemes have value, but creating useful models to quantify large scale, non industry specific systems is as much an art as it is a science.

The thing that I find frustrating is that a small amount of good sense, applied on a case by case basis, would be a huge improvement from where we are at right now, but this idea that there must be some grand unifying theory of environmental sustainability is pervasive and ends up creating more problems than solutions, imo. It is not like there is a shortage of people who undestand physics, chemistry, or mathematics who would like to do something useful with their knowledge. What is sorely lacking is the political will to get serious enough about environmental issues to force industry to redesign processes with a priority on environmental friendliness, expenses be damned.

When I did my environmental sustainabilty classes as a part of my mechanical engineering studies, I noticed that the convoluted ideas and schemes we were presented with on how to quantify emissions were designed by someone who had received funding from what might be described as “big pollution” industries. The idea that all of this stuff is so complex that we need to spend years ascertaining how we can begin to make a start is just obfuscation and interference by those with vested interests in the status quo imo.

– it would be nice if the conversion factors didn’t have to be developed piecemeal on a project basis.

If the analysis were able to be complete, the total emergy would be path-dependent. It takes a lot of energy to get a gallon of gas to the Khyber Pass, or to get that trash to the landfill. The perspective is ecology, and (almost) all the energy on the planet comes from the sun. Emergy is a baseline, based on incoming solar energy per day, and essentially sums the energy lost to heat by inefficiencies. Two steps down a food chain, about 99% of energy has been blown off as heat. Emergy values help indicate how incredibly crazy low gasoline is priced.

For Odum that was a problem similar to the labor theory of value. A human is about a quarter-horsepower, so you can the estimate embodied energy, but what is valued on the market can actually be a loss in terms of energy as well as money.

The analyses are also like analyzing externalities in economics. We can analyze the spread of a plume of toxic waste, but the dollar value of that is a human value and thus arguable. What is the dollar value of loss to the Penobscot Indian Nation of a degradation of their way of life forever? They are the stakeholders with the most to lose, and in practice might have the best leverage to use this type of analysis effectively.

For the particular project, this is tough. How is the addition different from what was already allowed? If it is not, it’s hard to block. I noted a line about how just because part of the agreement can’t be enforced (like leaking leachate) doesn’t stop the rest from going forward. Like Wall Street, as long as they are screwing up the way everyone else is, their ass is covered.

I am all for doing these analyses, but for the activist purpose of stopping the landfill expansion, it could show a trillion dollar loss and still get swept into the wastebin. There are weak points, for example only accounting for a 25-year storm. You don’t need climate change to show a problem with that for downstream properties and ecosystems. Did you notice they’re bringing in more solid waste ash than solid waste? How do they know the out-of-state waste is meeting Maine standards on pulling recyclables? State-owned landfills have to meet the standard for incoming trash, I’m fuzzy about whether this company does.

When we stymied the toxic waste incinerator here, I’m pretty sure it’s because we convinced the local land barons that the value of their holdings would plummet. That is a major weak link that get’s responded to politically, though not necessarily openly. “Local government exists for one reason and one reason only: to decide how land gets used. Everything, and I mean everything, that local government does deconstructs to a decision about which landowners will win, and which will lose.” The PIN may have special standing as well.

I’d say more but I’d say too much.

The concept is sound, but I Don’t know about practicality. How far back do you you decompose each item? Just the energy to get the solar panel to where you install it? Or do you go all the way back to the raw materials and incorporate the energy to mine and smelt? There could be huge differences there. What about the shipping of components back and forth to China to get assembled? What about the length of time before replacing? If your solar panel brakes every week and needs to be replaced you are better off with coal.

It gets extremely complicated very fast. I suppose you could make assumptions and just not include a lot of stuff, but that might make a harder sell.

Does Nuclear Power Produce No CO2?

This was an excellent example of the sort of decomposition you’re talking about. (Sorry, the pictures don’t seem to be loading for me.) It helps show the implicit complexity involved. The story works because it’s answering a specific question, and clearly shows the rubicon is crossed.

With the landfill, what is the comparison to? ‘Good now bad later’ is how hyperbolic discounting works, delaying the cost into an uncertain future. Somehow it’s got to be shown to have a non-delayed effect. Then the complications only need to add up to cross some threshold of current unacceptability, and the analysis can stop.

Tracked down a more up-to-date link, with pictures!

Yup, Thats why they are working on biodiesel for trucks and planes. Also one more reason we need to get LFTR’s up and running ASAP. They are much more safe, and efficient. They really are the only bridge fuel we have as an option.

I don’t know if this was THE kind of reactor that NASA climate scientist James Hansen wrote about in the middle of his book Storms Of My Granchildren, but I know he wrote about SOME kind of nuclear reactor design. And said we had to adopt it and roll it out as fast as feasible in order to displace coal from the production of huge volumes of concentrated shippable electricity.

Lambert: … the necessity of a “reference level” …

PlutoniumKun: … the issue of commensurability, i.e. the difficulty of assessing different ‘values’ in one unit of measurement.

and Steve H.’s comment.

Without adequately grasping the exact scope and operation of the Emergy concept, it occurs to me that the use of several dimensions of measure could be used to address the issues of 1) need for localized/relevant baseline reference, and 2) the need to consider more factors than the net energy/emergy in a system or a state/condition within the system.

I’m still trying to find my way through the material, but a problem may be the value of certain configurations of material. Consider a door, (80″x32″x1.75″) it can be repurposed as a table, as a wall component, cut/broken into smaller segments for other purpose, and burned or otherwise rendered for (heat or other) energy. But if we burn it we have to make a new door when we need one. The door “depreciates” over time (weakens, contains less consumable energy, goes out of style), but it can be good to have old things around, available for unexpected eventualities.

This goes towards breadth of technology, how many ways there are to solve a problem, and how costly and sustainable various solutions may be, the contemporary “markets” concepts seem to overlook this a lot. Emergy lets us begin to thin in terms of total lifetime of material and energy processes, but so far I don’t see it recognizing value in preserving static conditions (of elements) outside of the context of depreciation. In the context of waste disposal, I’m referring more to reuse, repurpose, and reconfiguration, than to recycling of component material. I am imagining the emergy concept being used to justify (by assumption) needless or ill-considered disposal through consumption as energy, or similar component/constituent recycling, in cases where preservation has value (the extreme of that is the pack-rat mentality, save everything because who knows).

Real-world example: keeping around old (possibly but not necessarily broken) hard drives. Their working circuit boards and mechanical components can be used to resuscitate and recover data from busted drives (of similar model). Another example: old books no longer published (or older revisions) may contain information about events, culture, and context that may have value not only forensically but as alternative perspective on current issues.

Current form/configuration has value, and disposal is a somewhat suspect concept. Emergy doesn’t seem to map value in context outside of state transformation and energy flows. So it’s not a very complete measure for evaluation, even though it clearly adds depth to decision making. It seems to be examining processes in a very material context, there is at least a little more to life and value.

I notice that Western thought doesn’t do well with multiple (or dynamic) dimensions. Emergy may be more tractable if used in combination with measures along unrelated axes (such as, values of persistent form, eventual form).

Totally unrelated to your post but i perked up at the name Michael Burry–have just been watching The Big Short–and the link seems to be an ad for Guggenheim S&P Global Water Index ETF with Michael Burry as the tease. Water index funds–what joy. Air next.

As to the landfill, without some sort of out of state intervention the cause may be hopeless regardless of economic theory. I’ve been to Maine and also to Canada where miles of road will have thin lines of trees masking acres of clear cut behind them. There seems to be some sort of perverse contradiction where people who live in beautiful, remote natural places are economically desperate and more than willing to trade the eco future for jobs and the here and now. Perhaps the relevant variable is not joules but who is making the decisions.

Impressionalistically (neologizing), eMergy seems like a system to formally quantify externalities heretofore unquantified and hence unmeasured, uncounted, and not factored. I hope it catches on before it is too late to save us…

In my humble opinion, the problem starts with semantics. For quite some time now people have called waste disposal ‘landfill’.

Which is very misleading, since the land does not need to be filled and no land is filled into the land. It is simply filled with garbage. ‘Landfill’ has entered human consciousness as a way to get rid of unwanted products, manufacturing by-products and most materials that cannot be recycled – the majority of materials prior to the advent of recycling.

A convenient way to live the perfect consumer lives. Six to twelve month warranty over – trip to the garbage fill.

There is one way to address this important issue – in Maine and everywhere else:

Laws that prohibit the intentionally planned and built-in obsolescence. The mountains of garbage grew exponentially since the introduction of planned obsolescence. Increasing profits for the manufacturing corporations and at the same time a steady replacement industry.

Without planned obsolescence, we would not have to fill the land with unnecessary garbage. Together with the prescription of manufacturing processes that utilize reusable materials, the amount and extend of garbage fills would decrease.

Just a thought.

We do tend to call it a “dump.” That sure ticks the lawyers and lobbyists off….

(Dump picking is an honored tradition in Maine. But we can’t do it any more…)

Its all euphemisms. Incinerators are now ‘energy recovery facilities’. I’ve heard dumps described as land restoration projects (when filling in a quarry).

Back in the 1990’s because of a loophole in the law developers were allowed describe them as golf courses (if the material was non-toxic or biodegradable). All you had to do is persuade a local government to permit the golf course at a higher level than the existing ground. There is one golf course in Oxfordshire which is an average of 6 metres (18feet) above the pervious ground level.

Your worked example undermines your stated thesis- that the relevant unit of account is joules and not dollars. The forestry service is using emergy as a way of valuing ecosystem services in dollars. This highlights one of the biggest problems with using emergy (which I am in favour of): you still need to deal with prices. You can use emergy analysis to show what’s “actually” going on at a biophysical level but arguments about values/policy can’t be resolved at this level- the argument is then not that dollars are the incorrect unit of account but that prices come out of a partial accounting.

I remember Howard Odum being written about and thought about several decades ago in The Whole Earth Catalog / Co-Evolution Quarterly and also The Mother Earth News (magazine) at about the very same time. People were trying to find a reality-based way to understand real processes in the real world so they could live a real life in some small but real part of that real world.

I thought I had remembered Howard Odum being interviewed by Mother Earth News Magazine, but I couldn’t find that interview if it even really happened. So I found this interview instead.

http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00004025/00001/1j

I think I remember the word eMergy as being derived from eMbodied energy . . . meaning the energy having been burned to make a physical thing . . . and remaining legacy-useful and not needing reburning as long as that thing remained in physical existence serving a physical purpose.

It seems to me that the nuclear physichemist Frederick Soddy thought in some of these same ways but using his own language when he wrote the book Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt: The Solution of the Economic Paradox. That book might be worth reading in parallel with Odum books and papers.

The question arises . . . can the thinking activist come to understand Soddyism and Odumology so well that he/she can explain the knowledge and thinking tools and supplies they contain to layfolk, in the layfolks’ own language? If the thinking activist can do that, then a lot of layfolk may start applying Soddy-Odum analytical crowbars and tire irons to a number of kneecaps which need the treatment.

I read Soddy after Steven referenced him last year. Rereading Odum after that & noticed he directly referenced Soddy.

Here’s the deep issue: at the point of energy exchange the consumer doesn’t care about how much energy it took to create the product being consumed. Ballpark 90% of energy gets blown off at each trophic level, so a predator eating an herbivore who ate a plant which converted sunlight at 25%(?) efficiency is only getting is only getting 0.25% of the energy available when the primary producer transformed it. But that predator has a binocular vision and a brain that remembers things and a lot of fast-twitch muscle.

Don Lancaster has done some good work on this as well, from a practical perspective. I’ll paraphrase and say that consumers are concerned with energy density. We pay more per pound for fat than sugar, and gasoline is through the roof on the energy density metric.

Odum really did make the first steps toward understanding money from this perspective. A concrete example is the $4.99 bundle of firewood sticks at my grocery store, USDA approved, when you can pick them up in the forest for free. At least two steps confound the issue of money. The first is variable rewards, humans can imprint the weirdest stuff as being high-value. The second is insiderness: Howard Becker showed how art is valued through the patronage of wealth, and Wall Street runs on insider information.

In the Khazad-dûm deep is this issue: everything built in the universe is created by dumping externalities. The primal externality is entropy, and all that lives does so by dumping heat into the external environmental system. Nature doesn’t care how many billions of individuals die, as long as a couple survive to reproduce.

They may seem pessimistic, yet here we are, with brains that can see themselves, and engage with awe at the wonder of the universe.

I saw this article earlier but did not read the title closely enough and just read it now.

I’m surprised there’s no mention of natural capital accounting, which is becoming quite popular. Of course it has its limitations, but to me, it’s much more practical than this concept of “emergy.” Rather than having to go through problematic conversions, policy makers and capitalists now have an idea of the true monetary value of their decisions. Of course there are many problems with natural capital accounting, but in my opinion, it’s the best way to teach people that there are, indeed, externalities involved with every product they buy, and while they don’t pay for these external costs with the purchase of that product, society as a whole has to pay. This utter disregard for the four “frees” given to us by nature will ultimately be our downfall.