Yves here. This post identifies one set of factors that leads to ever-levitating CEO pay, irrespective of performance. We identified a central driver in a 2008 post, Have you Bought Into the Pay Double Standard?:

One meme I have noticed surfacing in the debate over the automaker bailout is that UAW employees are paid more than average workers.

Now in and of itself, that statement is meaningless. You need to have an idea of worker productivity to see whether that it out of whack (and for some odd reason, the bloated and highly paid management cohort almost never gets mentioned in these discussions, nor do the massive state level subsidies to the foreign transplants). Perhaps I missed it, but I do not recall seeing any longitudinal work on labor costs (that sort of analysis would help bring some badly needed facts to the table).

But why is framing the discussion around averages alone dangerous? Let’s say we collectively want to bring car worker pay down to some sort of average. That has the effect of lowering the average. You will have groups that were formerly at the average that are now above it. And if you accept the implicit logic “above average pay is bad” (fill in the blank as to why), you have a race to the bottom due to pressure on the relatively better paid to take less which puts pressure on aggregate pay.

I imagine now that some of you are snorting that the automakers are an isolated example and I am generalizing beyond a single (albeit very large example). Well, this sort of logic is at work, with a vengeance, but in reverse among CEOs. And it certainly has proven remarkably effective.

While most commentators on CEO pay correctly focus on the role of options-based rewards in goosing pay from generous to stratospheric, the role of compensation consultants seldom gets the attention it merits.

One practice that I have seen get perilous little mention is where the pay targets are set. Based on their belief of what constitutes good modern practice (influenced in no small degree by the pay consultants) most boards set general target ranges for how they would like the CEO to be paid relative to peers. The comp consultant then helps define and survey the peer group’s pay ranges, setting a benchmark for how the CEO in question is to be paid.

That all sounds fine, right? Well, except just as all the children at Lake Woebegone are above average, no board likes setting a target below peer group norms. I have heard of numerous examples of targets being set somewhere in the top half (66th percentile, top quarter, top 20%), hardly any at the mean, and none I know of below average (although GE’s Jeff Immelt set his pay at a remarkably modest level, saying it was bad for morale and inappropriate for the CEO to be paid vastly more than other C-level executives). If readers know of any examples of companies (other than those with substantially owned by insiders) where the target for CEO pay is below the median of comparable companies, please let me know.

So with this mechanism in place, any CEO who has fallen below median pay who is targeted to be in a higher group will have his pay ratcheted up, independent of performance, merely to keep up with his peers, This increase raises the average and creates new laggards. The comp consultants have institutionalized a leapfrogging process that keeps them busy surveying competitor reward levels and keeps top-level pay rising relentlessly.

And there seems to be a creep in cultural values that accepts, nay endorses, the opposite process at work further down the food chain.

By Brian Bell, Associate Professor, Department of Economics, and John Van Reenen Director of the Centre for Economic Performance and Professor of Economics at the London School of Economics. Originally published at VoxEU

Lacklustre growth seems to be the new normal almost everywhere in the world except for one area – the pay of chief executive officers (CEOs). For S&P500 firms, the average CEO made 31 times the wage of the average production worker in 1970, but this rose to 325 by 2008 (Conyon et al. 2011) and 335 by 2015. This has not gone unnoticed by politicians and the media.

CEO pay could have risen purely through market forces. For example, globalisation and technological change enables a CEO to leverage his ability (it is rarely “her”) over a larger scale. As the size of firms increases, so does CEO pay (e.g. Gabaix and Landier 2008). But other factors may also play an important role, as attested by many corporate governance scandals. And why does CEO pay rise when firm performance does not, or when firms do well for reasons unrelated to the talent or effort of the CEO (for example, in a stock market bubble or oil price boom)?

New Research

To provide fresh evidence on these questions, our new research uses UK publicly listed firms as a case study because since the late 1990s, there has been a major shift towards rewarding CEOs based on relative performance. A typical Long-Term Incentive Plan (LTIP) grants executives equity conditional on improving shareholder returns relative to a ‘peer group’ of large firms in the same sector (e.g. being among the top quartile of performers over a three-year period). These relative performance contracts contrast to more standard US-style stock option contracts that are based on general improvements in equity prices.

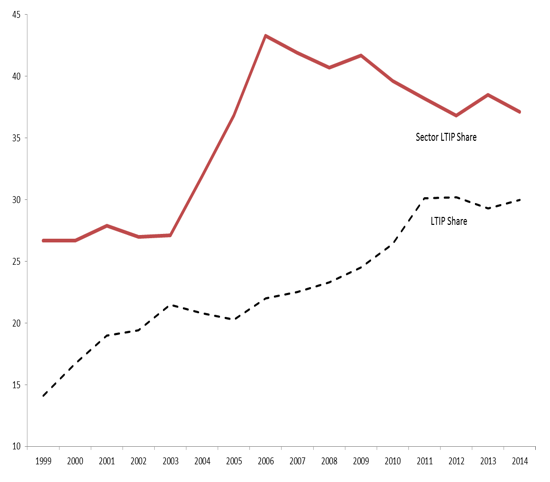

Figure 1 shows that at the start of our sample, around a quarter of LTIPs had a sector component. This share almost doubled over the course of the 2000s. At the same time, the share of total pay that was accounted for by LTIP awards also doubled. US corporations have also been moving towards these types of plan, but at a slower rate. De Angelis and Grinstein (2016) report that, by 2007 only 30% of S&P 500 firms used some form of relative performance evaluation in any part of their CEO pay package. As an early adopter, the UK experience can shed light on the efficacy of such plans. Unfortunately, we find that relative performance contracts and other LTIPs – all of which have some performance condition attached to them – seem to have failed to solve the problems of aligning CEO and shareholder incentives.

Figure 1 Share of CEO Pay in LTIPS and share of all LTIPS that have a relative component

Notes: “LTIP share” is the proportion of total CEO pay in the form of Long-term Incentive Plans. Sector LTIP Share shows the percentage of all LTIPs that have a sector component in the performance evaluation (i.e. are benchmarked against an industry peer average).

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Boardex data.

Using data on almost 500 firms that account for about 90% of the UK stock market, we show that there is a strong relationship between pay and performance for CEOs. This isn’t the case for lower-level employees, where incentive pay matters much less. To examine whether the pay-performance relationship reflects market forces we looked at two tests: ‘pay asymmetry’ and ‘pay for luck’.

Pay Asymmetry

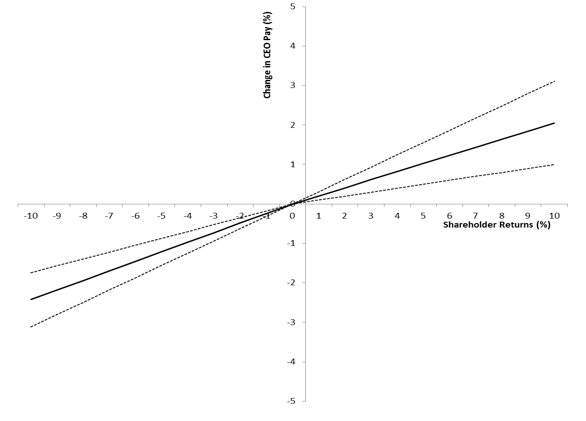

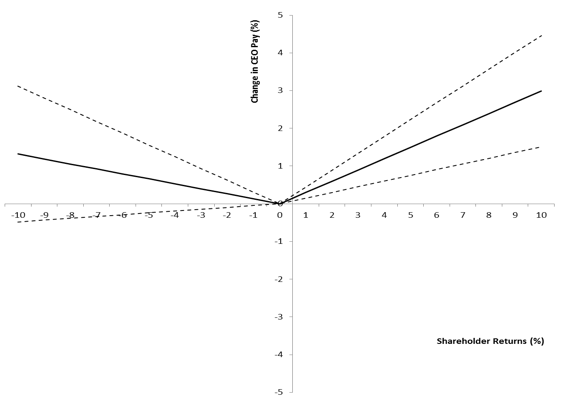

CEO pay is not symmetric – it responds more to increases in firm performance than to decreases. To explore whether this is because of corporate governance issues, we split the firms into two groups depending on whether a large share of the equity of the firm is held by institutional investors – since such shareholders are more likely to exert strong external control on the firm’s executives. We show that the asymmetry in pay is only observed when there is weak external control (see Figure 2 Panel B).

Figure 2 CEO pay is symmetric in well governed firms by asymmetric in badly governed firms (rising with good firm performance, but not falling with bad performance)

Panel A: Firms with strong governance

Panel B: Firms with weak governance (low share of institutional owners)

Notes: Theses figures represent the implied effect of a percentage change in a firm’s performance (as measured by TSR, Total Shareholder Returns) on the percentage increase in CEO pay. The coefficients are from the specification in column (5) of Table 4 of Bell and Van Reenen (2016). 95% confidence intervals shown. Strong governance is measured by a high share of Institutional Owners and weak governance by a low share. Panel A shows that in well governed firms the pay-performance relationship is symmetric whereas in badly governed firms, CEO pay does not fall, even when the firm does badly.

‘Pay for Luck’

Second, we found substantial ‘pay for luck’, i.e. CEO pay increased when the industry experienced a random positive shock. Surprisingly, this was still the case even when the CEO was subject to plans rewarding him for performance relative to the industry. The main reason for this was because CEOs were able to rig the system. When the share price underperformed, the top boss managed to extract some particularly juicy new LTIPs to make up for his expected loss of performance pay. This undermining of the system was only in firms that were weakly governed, consistent with the findings on pay asymmetry.

Concluding Remarks

The fundamental problem is that CEO remuneration packages are so opaque and complex that it is hard for shareholders to gauge their true generosity. Regulations to force more transparency will help, but are unlikely to be sufficient. Institutional owners, because they have greater resources and larger block-holdings, are more likely agents of change as they have the ability and incentive to be active monitors. Unless more of these investors step up to the plate, political calls for cruder and more direct intervention in CEO pay will become increasingly shrill.

See original post for references

“Institutional owners, because they have greater resources and larger block-holdings, are more likely agents of change as they have the ability and incentive to be active monitors. Unless more of these investors step up to the plate, political calls for cruder and more direct intervention in CEO pay will become increasingly shrill.”

Surely, the pension funds will save us from the guillotines!

The poster child of corporate looting would be IBM.

http://valleypatriot.com/h-1b-foreign-workers-are-destroying-merrimack-valley-economy/

Why bother with studies, etc.? If you were put in charge of the candy store and could take as much as you wanted, wouldn’t you? Of course you would. And the beauty of stealing money instead of candy is you don’t get a tummy ache.

CEO’s, cross-populated boards, and corrupt compensation consultants all work together to steal as much as possible. I don’t think most of them would even consider this stealing, though. Their egos are huge and are pumped bigger every day by fawning media and cowering employees.

You could put my cat in charge of any Fortune 500 company and it would do no better or no worse than any of the criminals presently running it.

Could it be that CEOs aggressively recruiting members of their own cohort to serve on the Board of Directors of their corporations have anything to do with it? Gosh. The back scratching boards involve other CEOs and cronies for whom a pay increase for the CEO is always warranted, because, well, … gosh, he’s a swell guy!

How much people make is not based on production, rather, it is based on how much control they have over other people.

When people unionize, they have more control over the corporations and hence they get paid more.

When CEOs have control over people or an industry they get paid more. This control is usually accomplished by rumor, marketing, or already attained wealth.

We need to stop kidding ourselves that how much money one earns under a capitalist system is based on worth, when it is only based on how much leverage and control one has over their neighbor.

This leapfrogging process is exactly why compensation for police and firefighters keeps rising relative to other professions. Police and firefighters have the advantage of appealing to an arbitrator to settle impasses in negotiations about wages and benefits.

These arbitrators, in turn, have to follow state laws which specify that pay and benefits of any one jurisdiction should be the same as other similarly sized jurisdictions, not only in the state, but also in the region, or even across the whole country.

How or why these other jurisdictions came to pay their police and firefighters the amounts they do does not factor into the decision by the arbitrator. The only thing that matters is what are they paid, not why.

So, any time one jurisdiction gets an out-sized pay raise, whether by poor negotiating by the management side, collusion, corruption, by mistake, by incompetence, or any other means, it gets passed onto the other jurisdictions by the formula set by the state law as their contracts come up for re-negotiation. You can see that these groups can get tremendous leverage by finding the weakest jurisdictions and applying whatever pressure they can to bear on obtaining higher wage levels, and then turning around and saying “hey, look, they pay a lot more in (insert weak city X), and we should get that now, too.) And the leapfrogging continues in a self-reinforcing way.

Essentially, police and firefighters have their pay set by arbitrators with a finger to the wind, and laws which force them to increase pay to the next highest level, no matter how or why that new level was derived.

The other side of this problem it that police officers and firefighters are forbidden from exercising the strike. This designated “essential public health and safety” for government workers has been extended to public hospitals, prosecutors, and public defenders, among others. Without the right to strike or engage in work slow-downs and other job actions without being subject to discipline or termination, what can these workers do when they work in high cost-of-living areas? Suck it up because they get to ride with the Dalmatian on the truck and ring the bell?

The problem in these circumstances is the pervasive political corruption that exists in the United States. The traditional kind (envelopes full of money), and the modern kind (catching politicians with their hands in the cookie jar and engaging in blackmail). I have been involved in a labor negotiation that might have looked very much like the latter model, and I can vouch that it works quite persuasively.

Arbitration of “essential public health and safety” contracts isn’t the problem, unless you think that it’s a good idea to have the local fire department out on strike (although a strike at certain police departments might present a different societal conundrum). Nobody wants to be intubated by a scab paramedic.

> cruder and more direct intervention in CEO pay

One can imagine…

Perhaps we should start offshoring CEO type jobs to Japan of Australia to start, as it is my understanding the the excutives of large companies are paid in much lower multiples of the average salary within the company. There’s really no reason why the executive decisions cannot be made halfway around the world as opposed to the company’s nominal home.

I have long been of the view that a financially prudent employer looks for bargains. When hiring a CEO, a financially prudent board of directors should be looking for a bargain, which is to say a CEO for less than average cost. I would think that a reasonable comparative target would be to pay the CEO at the 25th percentile of pay for comparable positions.