By Kurt Mitman, Assistant Professor, Institute for International Economic Studies, Stockholm University, Dirk Krueger, Professor of Economics and Chair of the Economics Department, University of Pennsylvania; Research Fellow, CEPR, and Fabrizio Perri, Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Minnesota and a consultant at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Originally published at VoxEU.

The Great Recession of 2007-2009 was the major macroeconomic downturn of the postwar period. It happened when several measures of household inequality were at a postwar high. Is there a connection between these two observations? Did the high level of household inequality amplify and propagate the Great Recession? How are the welfare losses in an economic downturn, such as the 2007-09 crisis, distributed across households, and can social insurance policies mitigate these losses?

In a well-known paper published in 1998, Krusell and Smith concluded that household income and wealth inequality had little impact on the aggregate dynamics of consumption, investment, and output. Their model economy had heterogeneous agents and incomplete markets, and it behaved much like a model that used a representative household. This result has reinforced the continued use of representative agents when studying the macroeconomy.

In a recent study, we revisited the importance of household heterogeneity for aggregate consumption and output dynamics (Krueger et al. 2016a). Unlike Krusell and Smith, we found that inequality has a significant impact on business cycle fluctuations. In other words, we find that micro heterogeneity is important for macro outcomes We also explored (Krueger et al. 2016b) how large downturns differentially impact household welfare depending on wealth, employment, and how social insurance affects those welfare losses. We find that the macro shocks can have a sizeable impact on household welfare and one that is different across the wealth distribution, in other words, macro dynamics are important for micro outcomes.

Wealth Inequality and Consumption Rate

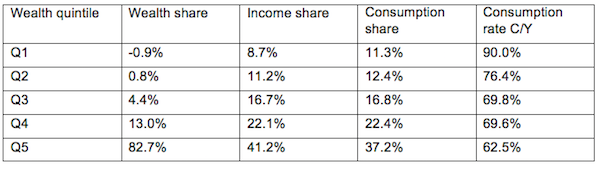

Table 1 shows some key facts about the US income, wealth and consumption distribution in 2006, just before the great recession. It is taken from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), a household survey that has been running since 1968. It collects information about household wages, labour market outcomes, wealth, and comprehensive measures of household consumption expenditures. To construct the table, we sorted households by wealth measured as net worth (the value of all households assets, financial and real, including the value of a household’s home, subtracting all household liabilities such as mortgage debt). We report the share of economy-wide net worth owned by households in each of the five quintiles of the wealth distribution.

The third and fourth columns summarise the share of disposable income and consumption for households at different points of the wealth distribution. The last column calculates the expenditure rate by wealth quintile, measured as the ratio of total consumption expenditure to total disposable income for each quintile.

Table 1 Distribution of wealth, income and consumption by wealth quintile

Source: PSID.

Clearly, wealth is extremely unequally distributed in the US. The bottom 40% of households hold no net worth at all, while the upper 20% hold 83% of total net worth. The highest wealth quintile holds a disproportionate share of aggregate income and consumption too.

But despite holding virtually no wealth, the bottom 40% of households still account for close to 25% of aggregate consumption. As the last column of Table 1 shows, households at the lower end of the wealth distribution consume a larger share of their disposable income. Therefore, we would expect their expenditures would to respond more strongly to a large and prolonged economic downturn.

Did Household Inequality Amplify and Propagate the Great Recession?

To investigate this, we constructed a standard macroeconomic model with aggregate shocks and household heterogeneity in incomes and preferences, using Krusell and Smith’s method. But we ensured that our model had cross-sectional wealth and consumption distributions that replicate the PSID data. In our model, highly persistent income shocks, coupled with unemployment insurance, mean the bottom 40% in the model held no wealth, but made up a significant share of consumption. A group of especially patient households made up the top of the wealth distribution, and accounted for approximately 80% of all wealth in the economy.

We then subjected our model economy, as well as an economy with much greater wealth equality, to the same large negative shock. This was a drop of total factor productivity of 4% relative to trend, expected to last 22 quarters. For the model with 2006-like wealth inequality, compared to an economy with little or no wealth inequality, the consumption expenditure recession on impact is half a percentage point larger, representing about $200 per capita,. Figure 1 illustrates this.

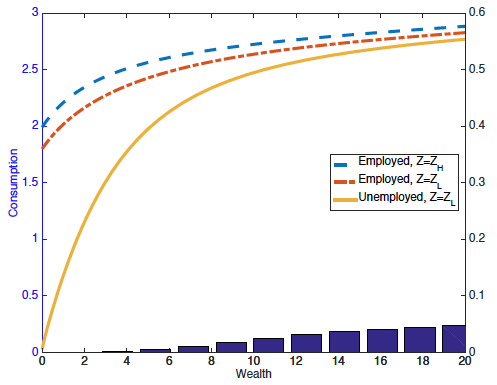

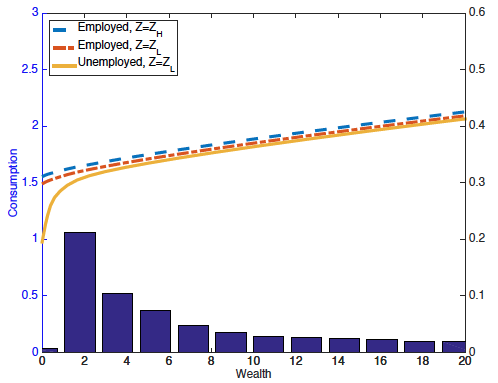

Figure 1

This figure displays the consumption functions and wealth distributions from two models. ‘KS’ is based on the model economy studied by Krusell and Smith. It allows only limited wealth inequality. On the other hand, our model’s cross-sectional wealth distribution in 2006 is consistent with that in the data. The left-hand panel shows the KS economy, with consumption functions (plotted against individual wealth on the horizontal axis) for three combinations of idiosyncratic employment and aggregate productivity states. For a given wealth level, the vertical difference between the consumption functions for the employed in aggregate state Z = Zh (the blue dashed line) and the employed in aggregate state Z = Zl (the red dot-dashed line) gives the consumption drop in the Great Recession, conditional on not losing a job. In the same way, the vertical distance between the blue-dashed consumption function and the orange solid consumption function (for the unemployed in the recession) gives the consumption decline for those households that lose their jobs. The figure also shows the pre-recession wealth distribution, displayed as a histogram.

The right-hand panel displays the same information, but for an economy that uses 2006 data.

For a given level of wealth we can see that the drop in individual consumption in the KS economy in the Great Recession would actually have been larger than in the benchmark economy. This is mainly because the benchmark economy has a more generous unemployment insurance system that stabilises individual consumption. This is especially true for households with little wealth that lose their jobs at the onset of the recession.

These larger individual consumption declines in the KS economy might suggest that the aggregate consumption recession is also larger for the KS economy than for the 2006 benchmark economy. This is not so. In the KS economy, the cross-sectional wealth distribution places almost no mass on households with very little net worth. In contrast, the benchmark model with realistic wealth inequality has many households at zero or close to zero wealth. For these households, the individual consumption losses are significant. This is especially true for newly unemployed households. Therefore the aggregate consumption recession is significantly larger when the bottom 40% of the population has close to zero wealth than in a more equal distribution.

We would like to stress that the reason why the aggregate drop in expenditures is much larger in the economy with many low wealth consumers is not driven by the fact that low wealth households are ‘hand-to-mouth’ consumers, who cut their expenditure one-for-one as their income falls. It is instead explained by the fact that low-wealth consumers have a lesser ability to self-insure against idiosyncratic risk, so when the recession hits and unemployment risk increases, they drastically reduce their expenditure rates, even if their income has not dropped yet. Interestingly this is a prediction of the model, but is also observed in the PSID data. For example, in our work we document that over the course of the Great Recession, households in the bottom quintile of the wealth distribution reduced their expenditure rates by roughly 4 percentage points, while those in the top quintile only cut their expenditure rates by 2 percentage points.

How Are the Welfare Losses In An Economic Downturn Distributed?

The size of a public unemployment insurance (UI) programme affects the wealth distribution, but also the size of the individual consumption decline in a recession for a given wealth level. Holding the wealth distribution constant, a less generous system of UI (a reduction of the UI replacement rate from 50% to 10% in this case) amplifies the aggregate consumption recession by two percentage points. When the wealth distribution responds to the policy change, three quarters of this amplification disappears.

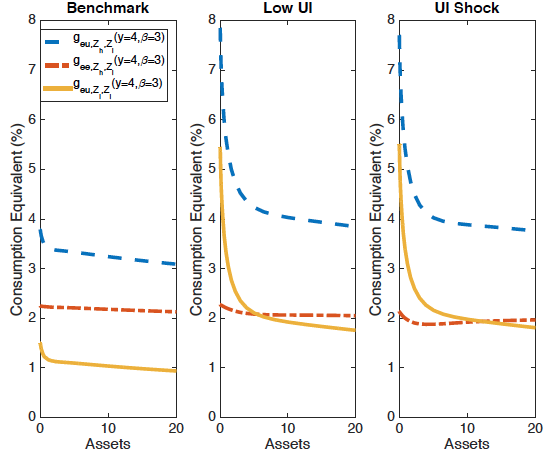

Figure 1 showed that the decline in individual consumption in the Great Recession would have differed strongly among households depending on their wealth levels and whether they lost their job. It therefore is likely that the welfare losses were unevenly distributed across the US population, and shaped by the size of social insurance programs such as UI.

In the second part of our research, we showed that this is indeed the case (Krueger et al. 2016b). Using the same set-up described above, we tried a thought experiment: what share of lifetime consumption would a household be willing to give up to avoid seeing the macroeconomy slip into a 2006-style ‘great recession’?

Figure 2 summarises the results. The three panels differ according to the size of the UI system: a replacement rate of 50% in the left-hand panel, a replacement rate of 10% in the middle panel, and a surprise reduction of the UI replacement rate at the time of a great recession from 50% to 10% (think of UI benefits unexpectedly running out) in the right-hand panel. Each panel plots welfare losses from the economy falling into a great recession (red dashed line), losing one’s job (orange solid line) and the combination of both events, against wealth.

Figure 2

We observe that these welfare losses are large (up to 8% of lifetime consumption), substantially larger if the UI system is small, and significantly larger for households with little wealth. If UI benefits are generous (see the left-hand panel) the aggregate component of the welfare losses is larger than the idiosyncratic component of losing one’s job. Primarily this is because future unemployment risk goes up in aggregate downturns – even for households that have not yet lost their jobs, and we attribute this added unemployment risk to the aggregate welfare loss component. In the benchmark economy with realistic wealth inequality, aggregating across households, the welfare losses from the great recession were 2.2% of lifetime consumption; in the economy with limited wealth dispersion the losses were only 1.6%. This was mainly because the KS economy has few people with little wealth, and it is these households that suffer the most from experiencing a great recession.

Taking both of our papers together, we conclude that measuring and modeling household heterogeneity explicitly is of crucial importance in macroeconomic research for two reasons.

- The first is that macroeconomic dynamics are affected by the degree of underlying heterogeneity. In particular, an economy with a large fraction of low-wealth households will experience a sharper reduction in aggregate consumption expenditures in response to a given macroeconomic shock.

- The second reason is that, in terms of welfare, the impact of a given macroeconomic shock is felt very differently in different segments of the wealth distribution. In particular, low-wealth households have limited capacity to insure themselves against idiosyncratic risk, and thus the welfare impact of a recession is significantly larger for them. As a consequence, ignoring wealth heterogeneity can severely underestimate the welfare cost of a large recession.

References

Krueger, D., Kurt Mitman and F. Perri (2016a), “Macroeconomics and Household Heterogeneity“, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 11038.

Krueger, D., Kurt Mitman and F. Perri (2016b), “On the Distribution of the Welfare Losses of Large Recessions“, CEPR Discussion paper 11413.

Krusell, P. and A. Smith (1998), Income and Wealth Heterogeneity in the Macroeconomy, Journal of Political Economy, 106, 867-896.

It’s good to see some empirical analysis generated which illustrates the plight of those on the bottom of the economic ladder when the economy is forced into a deep recession by yet another rupture within the FIRE sector of the economy.

It validates what is probably intuitively obvious to most objective observers that during severe recessions, a drop in consumption expenditures of the lower classes will occur, due almost entirely to (1) unemployment, and (2) the collapsing sales of big ticket items + houses, purchases which are almost always paid for with borrowed money.

The real tragedy of the 2008-2009 recession is that policy makers did not immediately take actions to insulate the Main Street economy from the disastrous machinations of Wall Street and the banking industry.

In the U.S., this could have been done if Congress had ignored the advice of the financial geniuses who had created the disaster (to make good all their bad bets at the casino) and had chosen instead to immediately create a Taxpayers’ Bank, built upon the ashes of the private institutions that were facing bankruptcy.

Authorized and underwritten by Congress, the Treasury could have (1) bought the assets of failing banks and insurers for pennies on the dollar, (2) fully capitalized them with taxpayer $$, and then (3) have fully provided for all the ‘plain vanilla’ banking needs upon which the Main Street economy depends.

This approach, when combined with a massive increase in government spending on infrastructure and human capital, would have created an economic boom that would have quite happily sustained the Main Street economy while the FIRE sector was allowed to crash and burn utterly.

Within a year’s time, the recession would have been over, full employment would be achieved (if the increase in aggregate spending was adequate) and the the tremendous amount of suffering we’ve seen over the last decade would never have occurred.

This solution would have finally restored moral hazard to the financial industry and it would have imposed a punishment on the titans of the industry that they so richly deserved.

There has never been any reason why modern economies should be utterly dependent upon wealthy speculators for the plain vanilla banking services that the Main Street economy is utterly dependent upon.

If private bankers want to chase higher yields by taking on higher risks, then let them, but do absolutely nothing when their bets go wrong. No deposit insurance. No bailouts by the CB. Let them lose everything. They will learn what takes to live with moral hazard.

It is sad that, even today, there is no recognition among economists that plain vanilla banking services are something national governments can provide at a minimal cost to those who use them, and that if they do so, it will provide the general public, and the Main Street economy, with 100% protection from the incredible damage that the machinations of the financier class can inflict upon the whole of society when their schemes go bad.

Even Bernie Sanders—who has never been afraid to advocate a ‘socialist’ alternative when it makes sense—did not recognize that this is one element of socialism that is absolutely essential if you want to protect the denizens of Main Street from the nefarious doings of the financial elite.

Forget about Glass-Steagall; fix the economy’s dependency on the Bankster mafia in a way that actually guarantees the salvation of those who work for a living…

Thank You. Your comment is perfection.

Thanks for an admirably concise and precise comment.

It’s much more stimulating to the economy to helicopter money directly to the lower rungs of society, because they will spend it. Instead they helicoptered it directly to the banksters (as they were ordered to do by Happy Hank Paulson)—and these bad boys only used it for more speculation.

Even if the distribution of wealth/income doesn’t affect aggregate consumption, it certainly does affect what is consumed. If more people are buying more different things are bought, just because of individual variations in needs and interests. There will be many more niche markets in economies where wealth/income is widely distributed than in ones where wealth is highly concentrated, thus more opportunities for workers and companies.

But all Serious People know that helicoptering money to the lower rungs is just WELFARE, and that interferes with the market and is WROUGHT with fraud!

Here is an article that looks at the relationship between wealth and ethnicity/race in the United States:

http://viableopposition.blogspot.ca/2016/08/the-growing-ethnicracial-wealth-gap.html

The notable presence of public policies that exacerbate racial and economic inequality and the lack of will by Washington to change the system mean that the ethnic/racial wealth gap is becoming more firmly entrenched in society.

A lot of impressive jargon. Why not write this so a college graduate can understand it

*shrug* dunno, this college dropout understood it just fine.

I’m with you. All the jargon and charts are less convincing and certainly less easily understood than a simple walk down the main street of many of our small cities [possibly a bad idea to walk alone too far along main street in many of our larger cities]. And look into the eyes of the people you see [small city of course]. I feel uncomfortable with all the jargon and charts and add in some higher math because of how often they are used to reach and sometime prove false conclusions. According to a math professor I had — back in the day — economists are notorious for errors in using higher math optimizations to prove various falsehoods.

Naked capitalism was not the original audience. Also, many other commenters here understood it fine. Not every article is going to suit every individual reader. Besides I bet you got the main message – economists assume that inequality doesn’t matter at a general level. This paper shows that it does. And if people with power care about the economy that sustains their power then it is in their best interests to reduce income and wealth inequality. Since policy types read these kind of op-eds (less complicated than journal articles), and are impressed by mathematical models, it is a good thing.

Inequality.

Turning economics up the right way again should help.

Let’s look at the world today.

1) An excessive concentration of capital at the top

2016– “Richest 62 people as wealthy as half of world’s population”

Many investments now have negative yield due to the deluge of investment capital at the top. There is no return on these investments; you have to pay people to take investment capital off your hands.

2) A lack of capital at the bottom

Policy makers are talking of subdued global aggregate demand and putting forward solutions like helicopter money, redistribution through taxation and fiscal stimulus. Fiscal stimulus creates jobs and wages through Government spending which can be spent into the economy

Let’s ask the fundamental question.

Why was economics turned upside down?

When you turn economics upside down you suddenly get all the wrong answers.

How strange!

40 years ago, most economists and almost everyone else believed the economy was demand driven and the system naturally trickled up.

Now most economists and almost everyone else believes the economy is supply driven and the system naturally trickles down.

Economics has been turned upside down in the last 40 years.

If it was still the right way up we would have been doing fiscal stimulus (Keynesian stimulus) eight years ago.

Having an economy that is demand driven and trickles up (which is the way it actually works) wasn’t good for those at the top who had to pay higher wages (to keep demand going) and higher taxes (to stop the system polarising from trickle up).

They thought they would just turn economics upside down and the real economy would follow (King Canute Syndrome).

They paid workers less and have stifled demand in the global economy.

They paid lower taxes leading to the polarisation of personal wealth.

King Canute got his feet wet, turning economics upside down has laid waste to the global economy.

Our view of capitalism is upside down (UK based).

We know those at the bottom who don’t work are supported by benefits.

How are those at the top supported who don’t work, like the Aristocracy and associates of the Royal Family who parade their idleness in the tabloids?

Capitalism is the welfare state of the idle rich.

The company’s employee’s output is sold in the market and the revenue is split into paying wages, covering costs and profits.

The slice going to profit, ensure employees get less out than they put in.

The business owner does not employ people to make them rich, the idea is profit and paying them as little as they can get away with.

A company is not a charity and is not there for the benefit of employees, it’s there to make money for investors or business owners.

The investor expects to take out more than they put in.

The idle rich, with trust funds, lead lives of luxury and leisure with the income from their trust funds, while the trust fund never actually loses any value.

They put nothing in and take a lot out.

Capitalism takes the hard work of employees and redistributes a portion of the fruit of their labour upwards.

As Adam Smith observed in the 18th Century:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

Capitalism is the welfare state of the idle rich.

Marx was impressed with its efficiency.

We just need some redistribution externally so the whole thing doesn’t polarise.

We had raw Capitalism in the 19th Century, it produces very rich people and very poor people and it does not support a consumer society.

By the 1920s, mass production techniques had improved to such an extent that relatively wealthy consumers were required to purchase all the output the system could produce and extensive advertising was required to manufacture demand for the chronic over-supply the Capitalist system could produce.

Modern capitalism needs external redistribution to keep the whole thing going.

(or the FED can keep on with NIRP and ZIRP to try and encourage consumption, it doesn’t seem to be working)

Read the Wealth of Nations, when everything was obvious and there were no excuses as there was just small state, raw capitalism.

Try other Classical Economists from this era too.

What else did Adam Smith observe?

“But the rate of profit does not, like rent and wages, rise with the prosperity and fall with the declension of the society. On the contrary, it is naturally low in rich and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin.”

Exactly the opposite of today’s thinking, what does he mean?

When rates of profit are high, capitalism is cannibalising itself by:

1) Not engaging in long term investment for the future

2) Paying insufficient wages to maintain demand for its products and services

Adam Smith would understand why Amazon grew so big by re-investing, not taking profits and not paying dividends.

He would also understand today’s problems with demand (low wages), growth (lack of investment) and productivity (lack of investment).

Anything else?

“The proposal of any new law or regulation of commerce which comes from this order ought always to be listened to with great precaution, and ought never to be adopted till after having been long and carefully examined, not only with the most scrupulous, but with the most suspicious attention. It comes from an order of men whose interest is never exactly the same with that of the public, who have generally an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public, and who accordingly have, upon many occasions, both deceived and oppressed it.”

He has the mindset of today’s lobbyist, who generally have an interest to deceive and even to oppress the public.

I remember this system we used to have when I was younger.

It was called Capitalism, but it led to the lowest levels of inequality in history within the developed world.

It led to the golden age of the 1950s and 1960s.

It was developed from the unfettered capitalism of the 1920s that led to massive inequality, a Wall Street crash and a global recession.

It used strong progressive taxation to provide subsidised housing, healthcare, education and services for those lower down the scale.

We have had another bout of unfettered capitalism and it has led to massive inequality, a Wall Street crash and a global recession.

Maybe we just need a “New Deal”.

Discussions of inequality seem to center on matters of fairness and matters of economic efficiency. It is unfair for “X” to keep so much and share so little — and if “X” doesn’t share then the many “y’s” are unable to buy products.

What about power and control? We can tolerate a certain level of inequality in our economy — fair or not and efficient or not but our democracy cannot tolerate the levels of inequality which places power into the hands of a chosen few — chosen for their manifest egregious and anti-social traits — to control the direction of our polity and the lives of our people.

I agree. In other words: discussions about economic inequality have to consider the tipping point from where the republic will turn into feudalism.

But maybe we are already there. One of the revolutionary ideas of the republican system is that you do not get your social status based on bloodlines. But Canada has Trudeau, the US is painstakingly avoiding to call its presidents Bush I and Bush II, Hillary Clinton is regarded as the first woman and not the first wife in the White House, while rumours about mom & dad prepping Chelsea for the White House abound. In Europe, Marine Le Pen has inherited the chair of Le Front from papa, in Germany Schäuble’s daughter is heading the 1 billion public production company DEGETO while Schäuble’s son in law has suddenly become #5 in the CDU and cabinet minister in arguably one of the 3 most powerful Bundesländer.

But hey. Maybe I’m just being selective here.

Unless and until you hear Clinton or Trump say words to the effect ‘ Watch out Blankfein, watch out Dimon I’m coming for you ‘ you can be sure nothing is going to change and no amount of handwringing will stop the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer . Until that is when the day comes and something goes ‘ pop ‘ and the next thing you know is there is a very large crowd outside the White House demanding the head of the incumbent and the police and the army are not prepared to stop them. ” Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will ” .

The greatest question facing the world today is:

“Which way is up?”

40 years ago, most economists and almost everyone else believed the economy was demand driven and the system naturally trickled up.

Now most economists and almost everyone else believes the economy is supply driven and the system naturally trickles down.

Economics has been turned upside down in the last 40 years.

For a supply side, trickle down world you need Neo-Keynesian stimulus where money is fed into the top of the economic pyramid the banks to be lent out, invested and trickle down.

For a demand driven, trickle up world you need traditional Keynesian stimulus where money is fed into the bottom through infrastructure spending to create jobs and wages which will be spent into the economy and trickle up.

The West has been doing Neo-Keynesian stimulus for the last eight years and asset prices have been maintained but little has trickled down to the real economy.

China has been doing Keynesian stimulus for the last eight years and had been the engine of the global economy, until it realised this stimulus was costing too much and debt levels were getting out of hand.

China never rebalanced its economy towards consumption and was hoping the Western consumer would have come back to life in the eight years it was doing Keynesian stimulus, unfortunately this didn’t happen as the West did the upside down, Neo-Keynesian stimulus.

China itself believes in supply side, trickledown economics which has led to massive inequality and almost no welfare state. The vast majority of consumers are forced to save for a rainy day and wages are low subduing consumption. A few have accumulated most of the wealth from the boom and have been busy spending it abroad mainly in high end property.

China engaged in Keynesian stimulus because of Japan’s experience in a 25 year balance sheet recession where only Keynesian stimulus was found to work. It did what was known to work in the last eight years, but still fundamentally believes in supply side, trickledown economics. It is not suffering from schizophrenia.

The Central Banks are still in Neo-Keynesian stimulus mode and are willing to give money to anyone apart from consumers. Banks can have free money, companies can have free money, but the consumer must wait for it to trickledown to them and all the evidence suggests they will be waiting a long time.

Other policymakers are beginning to notice the failure of neo-Keynesian stimulus as hardly anything had trickled down in the last eight years. They are now coming up with ideas like helicopter money, re-distribution through taxation and Keynesian (fiscal) stimulus.

In an exact science like economics, we just need to determine “which way is up?”.