By Gareth Vaughan and Denise McNabb of www.interest.co.nz, and Richard Smith of Naked Capitalism. An earlier version of this post appeared at interest.co.nz before publication of the Shewan report on foreign trusts and the latest EU initiative.

Remember Allen Stanford?

Originally from Texas, Stanford’s the guy who showered 20/20 cricket with money shortly before his giant international Ponzi scheme came crashing down on him, resulting in Stanford being sentenced to 110 years in prison in 2012 for orchestrating a US$7 billion fraudulent investment scheme. A court bid by Stanford to overturn his conviction was rejected last year.

The Stanford empire stretched all the way to Wellington where, with the assistance of lawyer Gordon Stewart, Stanford established Stanford Trust Company (New Zealand) Ltd.

And when Stanford receiver Ralph Janvey and his team started looking for money and assets, their attention was drawn to Rebecca Reeves-Stanford of Key Biscayne, Florida. Reeves-Stanford was described as one of several “outside wives” with whom Stanford had an ongoing relationship. The receiver says Stanford provided Reeves-Stanford, with whom he had two children, with large sums of money and substantial gifts over almost two decades.

Reeves-Stanford bought a large estate in Key Biscayne for US$2.6 million in July 2005. She then sold the property in May 2009 for US$3 million. Her lawyers confirmed to Janvey’s team that at least US$1.4 million used to buy the property came from Stanford himself. And soon after the 2009 sale, Reeves “transferred the proceeds of the sale to the Cook Islands and New Zealand, in an apparent attempt to move the funds beyond the reach of the Receiver.”

Below is what the Antigua-based Stanford Trust Company Ltd said about NZ on its website, including touting the country as “an attractive jurisdiction for the establishment of trusts as tax planning vehicles.”

June 2007

Dear Clients and Guests,

Stanford Trust Company Limited, domiciled in Antigua, offers a broad array of trust and corporate services to clients worldwide – including the formation and administration of trusts and the formation of international business companies (IBCs) or personal investment companies (PICs) – and assists in other matters relating to trust and estate planning. Types of trusts include simple (interest in possession) trusts, complex (discretionary) trusts, accumulation trusts, protective trusts, and foundations.

Stanford Trust Company Limited’s professionals are committed to using their experience, know-how and professional relationships to help clients design the international trust that best protects their trust assets and estate while profitably investing assets and ensuring an orderly transfer of wealth to beneficiaries. Once a trust is in place, Stanford’s advisors continually monitor performance and factors that may impact it to determine whether situations or conditions merit changes.

Stanford Trust Company Limited has a representative office in Bogotá, Colombia and in the United States as Stanford Fiduciary Investor Services, with offices in Miami, Houston and San Antonio.

STANFORD TRUST COMPANY (NEW ZEALAND)

Stanford Trust Company (New Zealand) Limited provides access to the New Zealand offshore trust through its connections with the Stanford Financial Group global network of companies.Sophisticated tax planning structures

New Zealand offers an attractive jurisdiction for the establishment of trusts as tax planning vehicles. Stanford professionals can help in the creation and administration of numerous trust structures which provide benefits under the country’s tax laws, such as asset-protection trusts and pre-migration trusts.

Stanford Trust Company (New Zealand) Limited serves clients from offices in Wellington, New Zealand.

Sincerely,

Anthony R. D’Aniello, MBA, LLB, JD, TEP

President

Stanford Trust Company Ltd.

Major reputational damage narrowly avoided?

According to the US Department of Justice, the vehicle for Stanford’s fraud was SIB (Stanford International Bank), an offshore bank owned by Stanford and based in Antigua and Barbuda that sold certificates of deposit (CDs) to depositors. Stanford began operating the bank in 1985 in Montserrat, the British West Indies, under the name Guardian International Bank. He moved the bank to Antigua in 1990 and changed its name to Stanford International Bank in 1994. SIB issued CDs that typically paid a premium over interest rates on CDs issued by US banks. By 2008, the bank owed its CD depositors more than US$8 billion.

Comments from Mark McDonald, a New Zealander working for Grant Thornton, SIB’s liquidator, suggest NZ may have dodged a bullet, thanks to the US Securities and Exchange Commission shutting down Stanford’s global empire in 2009. Back then, the Stanford empire, eyeing up New Zealand’s “favourable tax laws”, was only just getting started with NZ foreign trusts. McDonald says Stanford Trust Company (New Zealand) Ltd was “in its infancy” during 2008/09.

“It was set up as a branch of STCL [Stanford Trust Company Ltd] Antigua to facilitate the incorporation of entities under NZ’s favourable tax laws. There were only four trusts set up through this structure. All the cash/assets under the four entities were held at SIB. No assets were recovered through STCL (NZ) Limited,” says McDonald.

Unaoil & the Panama Papers

Stanford, of course, is far from alone in embracing the secrecy and asset protection offered by NZ foreign trusts. There’s the Monaco-based Unaoil, a company at the centre of a global oil industry bribery network, according to Fairfax and The Huffington Post. Fairfax reported Auckland’s UnaEnergy Trustees as an important link in the chain.

Others publicly highlighted recently include Maltese Energy Minister Konrad Mizzi and the Maltese Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff, Keith Schembri. As reported by a journalist with access to the massive leak from Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca, The Australian Financial Review’s Neil Chenoweth:

Just weeks earlier, Muscat’s chief-of-staff, Keith Schembri, and Malta’s energy minister, Konrad Mizzi, had used New Zealand’s secrecy laws to set up two offshore trusts. These were to be linked to a secret Dubai bank account and to two Panama companies that Schembri and Mizzi had set up in 2013 through a Panamanian law firm.

The revelation of the New Zealand trusts has triggered ongoing crisis for Muscat’s government, but it also increases pressure on New Zealand to tighten its tax loophole for foreign trusts.

New Zealand’s 12,000-plus offshore trusts pay no New Zealand tax on foreign earnings. Their beneficiaries are not registered and their accounts are not filed with any public body. New Zealand regulators may demand this information, but it is not disclosed to foreign governments.

The TVNZ and Radio NZ journalists, along with Nicky Hager, who gained access to the so-called Panama Papers, have been reporting on the use of NZ foreign trusts by Mossack Fonseca clients. These include Eduardo Cunha, the suspended speaker of Brazil’s lower house of Congress who is accused of taking bribes, and the exiled former Prime Minister of Kazakhstan, Akezhan Kazhegeldin, who has been sentenced to 10 years prison on corruption charges in his absence, though by a regime that is itself notorious!

These reports also highlight the role of Auckland law firm Cone Marshall and its partner Geoffrey Cone, who now lives in Uruguay. As the TVNZ/RNZ/Hager team reported;

Both Asiaciti Trust and Cone Marshall were among several firms who lobbied the government in 2014 over fears the trust industry would be shut down by Inland Revenue (IRD). It followed a troubling report in which IRD warned the government that the industry was criticised around the world “along the lines that we are a tax haven.”

When emailed about Cone Marshall’s involvement with a company that helped hide Cunha’s wealth, Mr Cone replied “Fair cop on Cunha. We terminated the case as soon as we looked into the file, and wound up the trust.”

‘Hiding money from the authorities on behalf of people who previously had Swiss banks’

Elsewhere an intriguing player in the NZ trusts industry was Equinor Trust, which is now in liquidation. It was associated with the offshore operating, NZ registered building society Kiwi Deposit. Lachlan Williams, executive director of Equinor Trust, told the Reserve Bank it specialised in the establishment and operation of NZ foreign or exempt trusts for high net worth and wealthy families and was a wholly owned subsidiary of the Copenhagen-based Equinor International A/S.

As reported by interest.co.nz in 2013, Williams said Equinor was the responsible trustee for almost 150 trusts with assets “conservatively” worth more than €5 billion: boats, planes, real estate, bankable assets and share participations.

These revelations were made when Williams, a former councillor of the City of Boroondara in Melbourne, was asking the Reserve Bank to supervise and audit Kiwi Deposit’s compliance with anti-money laundering and countering the financing of terrorism laws at a time there was no anti-money laundering supervisor for non-bank deposit takers in NZ. The request was apparently aimed at helping Equinor avoid having to disclose customer details to Swiss banks.

Equinor Trust’s liquidator, Paul Sargison of Gerry Rea Partners, describes the business as; “A traditional fiduciary that basically just hides money from the authorities on behalf of people who previously had Swiss banks. I think that was the main reason it was set up.”

Sargison says “the interesting bit” of Equinor Trust was sold and gone before his appointment. This was the sale of “part of” its trustee services business to Allanzia Trust Services, now Suricata Trust Services, in 2013, Suricata’s financial statements say the intangible assets bought, being customer relationships, had a value of $100,000.

Companies Office records show Peter Wyllie, a partner at Christchurch law firm Helmore Ayers, as Suricata’s director and ultimate shareholder. Asked whether the Equinor business Allanzia/Suricata bought bears any resemblance to that described in interest.co.nz’s 2013 article, Wyllie said “no.” And asked whether he is Suricata’s beneficial shareholder, and if not whether he could say who is, Wyllie said; “No. Do you tell everyone all your confidential information?”

Williams is now believed to be in Indonesia.

Problems well known before the Panama Papers

The potential for the ethically challenged and illegal use and abuse of NZ foreign trusts were well known before the emergence of the Panama Papers. This was highlighted in a 2012 article by Tim Hunter, and by interest.co.nz contributor Terry Baucher after a 60 Minutes story the same year.

The Panama Papers publicity forced the Government to do something, or appear to be doing something. Thus former PwC chairman John Shewan was recruited to review foreign trust disclosure rules. Here are Shewan’s terms of reference.

Shewan’s appointment came after it emerged that John Key’s personal lawyer, Ken Whitney, was among industry players (along with Geoffrey Cone) to successfully lobby Key and Revenue Minister Todd McClay in late 2014 and early 2015 to stop an Inland Revenue Department (IRD) review of NZ’s foreign trust rules. Meanwhile, the TVNZ and Radio NZ reports include one showing that Mossack Fonseca’s man in New Zealand, Roger Thompson, drafted legal documents for foreign clients apparently telling them to avoid countries with tax information-sharing agreements with New Zealand. Mr Thompson says this is nothing to do with trusts:

Mr Thompson said the purpose was solely to preserve the status of its clients wanting to use a Look-Through Company (LTC), where foreign income passes through New Zealand to the company’s owners tax-free, rather than a trust.

“Some clients, particularly from civil law countries, are unfamiliar and uncomfortable with trusts,” he said.

“They are, however, familiar with companies, and a LTC enables them to use a New Zealand company to hold assets with similar effect to a trust.”

Naturally one wonders whether NZ LTCs are as easy to abuse as NZ Trusts. But that appears to be a subject for another time.

An arbitrage opportunity

So just what are the issues with NZ foreign trusts?

Let’s start by looking at how they came into being. It’s a good case study in unintended consequences. In a letter dated December 2014, the IRD sets this out, noting the rules were introduced in 1988 as part of a wider package of international tax reforms. IRD acknowledges they depart from international norms.

Most countries’ tax trusts on the basis of the residence of the trustee which was New Zealand’s previous approach. However, from 1988 New Zealand’s rules for the taxation of trusts are based on the residence of the settlor. The difference between the two approaches creates an arbitrage opportunity…

IRD goes on to say although taxation based on the settlor’s residence makes it hard for NZ residents to hide their assets offshore, it naturally follows that a trust with a foreign settlor is a foreign trust even when the trustees are resident in NZ.

A foreign trust that derives foreign sourced income will not be taxed in New Zealand on that income, assuming no New Zealand resident beneficaries. That income might also be free from tax in the foreign settlor’s home jurisdiction because New Zealand’s approach to taxing trusts differs from the international norm…

The rules were tightened somewhat in 2004 following pressure from the Australian Tax Office. Revenue Minister of the day Michael Cullen announced foreign trusts would be required to have an IRD number, keep records for NZ tax purposes, provide certain information when they are first set up in NZ or appoint NZ trustees, and provide information to IRD on a regular basis.

The law change will provide an effective mechanism for obtaining information on these trusts. New Zealand will collect, store and transfer the information to the relevant foreign tax authorities on request, and to Australia on an annual basis – as it has requested.

Despite this, IRD noted in its 2014 letter to English and McClay; “There is a concern that our regulation is not good enough. Also, it is difficult to enforce compliance with the rules.”

Although arguing that NZ is not a tax haven because tax havens are all about secrecy, IRD added; “The perception that we might be a tax haven are [sic] damaging to New Zealand’s ‘clean’ international reputation. This can only get worse in view of future developments by the OECD on BEPS [Base Erosion and Profit Shifting], harmful tax practices, beneficial ownership and AEOI [Automatic Exchange of Information].”

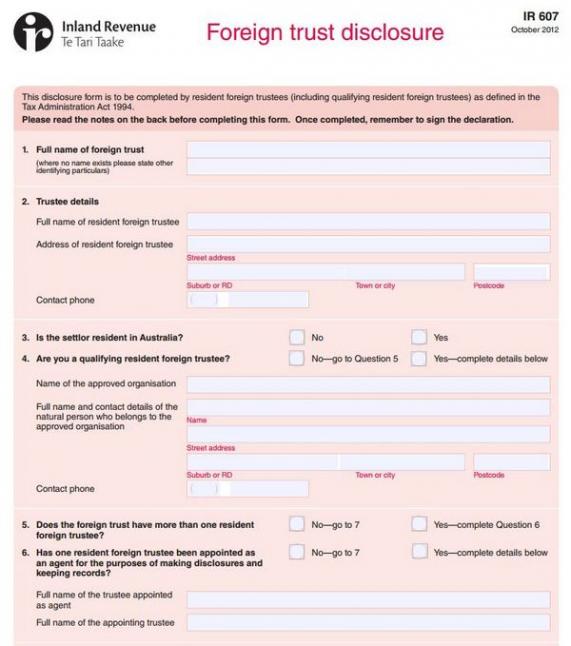

Below is the resulting eccentric foreign trust disclosure form, which augments the very modest default disclosure only when the settlor is a resident of Australia. Sadly, the rest of the world doesn’t get the same favour.

The arbitrage opportunity spotted – ‘the legal Fort Knox of asset protection’

Not surprisingly, the arbitrage opportunity was not lost on trust and company service providers. There are plenty of colourful pitches for NZ foreign trust business from them. Here are a couple.

This one’s from Trust New Zealand, part of Equity Trust International Ltd;

[The] New Zealand parliament has carefully legislated for the protection of foreign or non resident trusts and their assets. The New Zealand Foreign Trust regime is considered to be one of the best if not the best offshore trust regimes in the world today.

Trusts are considered sacred cows in New Zealand law and if properly structured cannot be set aside by a court, by a government, by a wife, by a creditor or by any inheritance disputes. They are the legal fort Knox of asset protection.

Trusts can trade, invest in assets of any kind, hold or sell property, invest overseas and even play on the stock exchange.

In 2007 by the Income Tax Act 2007 the New Zealand government legislated that any non resident that establishes a trust in New Zealand can utilise the trust to hold assets or invest in transactions or even trade and pay ZERO TAX IN NEW ZEALAND provided that the settlor is a non-New Zealand resident and the trust does not conduct any taxable activities in New Zealand.

In other words, a New Zealand trust will be a foreign trust if none of its settlors have been resident in New Zealand since the date the trust was first settled. New Zealand Foreign trusts are also known as New Zealand Offshore Trusts or New Zealand Non-Resident Trusts. A trust will cease to be a foreign trust if it makes any distribution after a settlor becomes a New Zealand resident, or if a New Zealand resident makes a settlement on the trust.

And;

New Zealand is one of the few jurisdictions that provides the added protection of trusts. That means creditors, spouses, governments and other claimants cannot get at your assets because these are owned by a trust, in New Zealand law a properly structured trust is unbreakable which makes New Zealand at a par with jurisdictions like the Cook Islands but without the stigma of offshore. In other words, if you put your assets into a trust structure then if properly structured no any party whatsoever can take your money. This is the secret that wealthy families have been using for years to protect the family money, and no New Zealand court will ever interfere or disturb this arrangement.

Former Equity Trust International director Evgeny Orlov, an ex-lawyer who recently relocated to Panama, also had this to say in 2012;

…how does one avoid the risk of heavy taxation, capital gains, and other nasty infestations of the tax systems of the first world, whilst having the flexibility to buy and sell property at will? What is the best structure to use for this and how do you minimise your tax burden on the profits made from international property investment?

…Those investing in property internationally should consider the benefits of doing so through a trust – in particular the New Zealand non resident (or foreign) trust.

If the New Zealand Foreign Trust is properly structured, its income and the assets are not considered to be your assets or income. Thus under all tax regimes (even the harsh United States regime which taxes world wide income) the income of the trust cannot be taxed in your hands.

Breder Suasso, which featured in our article about NZ financial service providers and whose Mauritus-based shareholder Theo de Regibus had a long stint at Mossack Fonseca, has also had some pretty colourful things to say about NZ trusts as reported here last year. Here’s a flavour;

“The New Zealand Foreign Trust regime is considered to be one of the best if not the best offshore trust regimes in the world today.”

And; “A properly established trust provides virtually 100% protection against creditors.”

Plus; “In New Zealand there are many cases of personally bankrupt individuals who have been unable to pay their taxes or have failed in business but who still live in mansions and drive Ferraris owned by their trusts and there is nothing anyone including the Government can do about it.”

Meanwhile, plenty of critics have pointed out foreign trusts’ flaws. Here’s Massey University senior lecturer in taxation Deborah Russell in a Spinoff article;

Although trustees here are required to keep records, they are not required to proactively file information with Inland Revenue. The only information that Inland Revenue collects each year is the name of the trust and the name of the trustee. In theory, we will collect information for other countries on request, but we don’t go on fishing expeditions, and other countries have to know enough in the first place in order to ask for the information.

And Tax Justice Network spokesman John Christensen argued in a TVNZ interview NZ’s double taxation and information exchange agreements touted by IRD and PM Key are “pretty useless” because they only work on the on-request model.

…if a tax authority elsewhere gets wind of the fact that someone might have a trust in New Zealand, then the courts might permit information exchange. That simply isn’t good enough.

How to fix the problem?

There are several approaches to fix the problem.

Labour Party Leader Andrew Little has suggested banning foreign trusts altogether; telling TVNZ; “I see no value in them. I cannot see what the purpose is apart from allowing others -you know, citizens in other countries to avoid their tax responsibilities in their home countries. And I’m at the point now where I’m saying, ‘Actually, unless I could be convinced otherwise, that we should just get rid of them.”

“I don’t see any value for New Zealand, and the only argument that’s been put up so far is they generate $24 million in fees for lawyers and accountants. Well, actually, that’s not a reason. If we want to talk about economic development, there’s other things we should be doing,” Little added.

Russell, meanwhile, suggests the best solution is to collect and disclose more information;

At a minimum, we should apply the rules we currently apply to foreign trusts with Australian settlors to all foreign trusts. That is, we should collect the names of settlors and disclose them to the relevant overseas tax authorities under our existing information sharing protocols.

However, I think that in addition to collecting the names of the settlors, we should also collect the names of the beneficiaries, and standard financial data, such as income earned, assets held and distributions made. This information should be shared with overseas jurisdictions using our existing information sharing protocols.

There would be no need to make any special rules with respect to penalties and filing dates and so on. These would all be covered by existing legislation.

If there are people who are using New Zealand foreign trusts for the purpose of avoiding or evading tax, then the prospect of having information disclosed to the relevant authorities in their own countries should be sufficient to encourage them to take their business elsewhere. Anyone who has a legitimate reason for using a foreign trust should still be able to do so, because they will already have been disclosing all the relevant information to authorities in their own countries.

Transparency International suggests a centralised register;

New Zealand should consider establishing a centralised register which maintains beneficial ownership information on all legal entities registered in New Zealand, any intermediate legal entities registered offshore, and final beneficial owners. This register should be accessed by law enforcement and regulatory supervisors. The register will be an effective tool to enable law enforcement to look through offshore vehicles in investigations where they may be used to disguise the beneficial owners.

A register would also allow New Zealand to provide timely and extensive international cooperation in investigations of tax evasion and corruption cases. The beneficial ownership registers should contain sufficient information about the trusts and companies to allow authorities to identify and understand the natural persons who exercise effective control over the corporate vehicles.

The definitions should ensure consistency with international standards set by the FATF [Financial Action Task Force] and OECD. For example:

for companies, this should include all natural persons with greater than 25% shareholding, and

for trusts, this should include information on the trustees, settlors, protectors (if any) and the beneficiaries of a fixed trust.

We further recommend that the Register be so configured to flag suspicious activity and registrations automatically to New Zealand enforcement agencies and regulators, rather than to allow it to be only interrogated only when an investigation is deemed necessary.

New Zealand has committed the implementation of the automatic exchange information (AEOI) requirements in 2017 and this will enhance the transparency of the foreign trusts. However, this should be extended to ensure that real time information is available on trusts for use by authorities.

Then there are the ideas of Ron Pol, a legal business consultant who has spent more than two years undertaking doctoral research for a political science PhD in policy effectiveness and anti-money laundering.

Pol points out offshore trusts and companies serve many legitimate purposes, such as for joint venture partners in different countries working on confidential transactions. Or for a well-known company to secure a big landholding through multiple shell companies in which its identity won’t be revealed so as not artificially to inflate prices, as Disney did before building Florida’s Disney World. Pol argues the issue for policymakers is not whether these characteristics are inherently good or bad, but they ought to base policies on recognition that these attributes, especially secrecy, are as attractive to some of the world’s worst criminals as they are for legitimate businesses.

Others suggest the likes of NZ foreign trusts can be used by nervous citizens of countries with corrupt governments to hide money and assets.

Pol suggests a “nuanced solution” could involve a beneficial ownership and activities register accessible only by tax and enforcement authorities.

The IRD and police can monitor for illegal activity, and have no interest in legitimate commercial deals. Legitimate businesses may be wary at first, but this is where New Zealand’s reputation carries weight, and competitive advantage. Combined with strict confidentiality provisions, matched in practice, businesses from around the world may be attracted to New Zealand, for all the right reasons. The world’s criminals may continue to deal with jurisdictions like Panama and Delaware if they protect the interests of criminal and legitimate enterprises without distinction, but criminals would find little to like about a genuinely ‘clean’ offshore trusts jurisdiction with ‘real time’ enforcement oversight.

Nor need a ‘clean’ model, shorn of any perception of illegality (and its associated reputational risk), represent any loss in value to the industry supporting it. Implemented well, the offshore trusts industry might instead experience growth if legitimate businesses the world over transfer their offshore business to New Zealand. The ‘Panama papers’ scandal illustrates the huge reputational damage for people and businesses associated with traditional secrecy havens that make little distinction between legal activities and the unsavoury business of the world’s criminals.

A ‘new model’ New Zealand option may therefore be attractive for hundreds of thousands of individuals and businesses who need a safe place to conduct legitimate business. French and American companies, for example, working confidentially to develop a joint venture in China might operate within the safety of New Zealand offshore trusts and companies.

A secondary benefit is that commerce should also be easier for legitimate businesses using ‘new model’ shell companies and offshore trusts. Banks will be more assured of their probity, without the flurry of red flags accompanying transactions conducted by shell companies operating from havens awash with the financial activities of organised crime groups and terrorists, (or even its perception, as undeniably associated with the inelegance of New Zealand’s current model).

Shewan’s report and recommendations, released at the end of June, include substantially all the suggestions of Russell and Transparency International, outlined above. As one might expect, one of the options, a public register, was rejected, for privacy reasons.

It’s not obvious, though, that there’s anything in the proposals that would allay the concerns of either Russell and John Christensen, which are echoed in the report itself in Section 10.6:

As a purely practical matter, because foreign trusts do not pay New Zealand tax or file tax returns, the extent of IRD audit work on them is generally limited to when a request is received from another country for information. Those occasions are few in number because offshore countries typically do not know that a foreign trust that they may have an interest in even exists in New Zealand.

Turning to section 12, one finds nothing in the level of disclosure proposed by Shewan that addresses this issue. It’s the key point that Tim Hunter raised back in 2012, and, anticlimactically, it is still open post-Shewan.

So: if a full public register including named beneficiaries is off limits, why not at least have a public register of trusts, including the nationalities (but not names) of settlors and beneficiaries? Perhaps this information should only be available if the settlors and beneficiaries reside in a country that has an information exchange agreement with NZ. That would at least give friendly foreign tax authorities a fighting chance, but it doesn’t feature in the recommendations.

After some cosmetic resistance, NZG accepted the Shewan recommendations in full; but that is not quite the end of the matter. Post-Shewan, the NZ press says that EU would like New Zealand’s Trust reforms to go much further, directly conflicting with Shewan’s proposal to keep the trust register private:

New Zealand is under investigation by the EU as it prepares a blacklist of global tax havens, Newshub revealed on Monday night.

The grouping of 28 European nations has compiled a list of countries with lax tax laws. Following the release of the so-called Panama Papers, it has confirmed that New Zealand is under investigation.

The EU is our third largest trading partner and worth about $7000 for every person in New Zealand.

The EU loses around NZ$1 trillion to tax havens each year, and it intends to put a stop to the practice by threatening a raft of sanctions against countries that don’t comply to its standards.

New Zealand doesn’t comply, even when the recommendations made by tax expert John Shewan as a result of the Panama Papers are included.

What the EU wants:

- No anonymity – trust settlers and beneficiaries are identified and changes are recorded. New Zealand will meet this standard when Mr Shewan’s changes are introduced.

- Collection of information about financial assets – where the funds came from, the current assets, where they are, and the income earned in the past year. New Zealand will meet this standard when Mr Shewan’s changes are introduced.

- No tax exemption of foreign income. New Zealand will NOT meet this standard even when Mr Shewan’s changes are introduced.

- Automatic exchange of information with foreign tax authorities in the jurisdictions where the settlers and beneficiaries are resident. New Zealand will NOT meet this standard even when Mr Shewan’s changes are introduced.

- A public register of trust ownership and details. New Zealand will NOT meet this standard even when Mr Shewan’s changes are introduced.

Non-complying nations face:

- Trade sanctions

- Suspension of negotiations for a free-trade agreement

- Possible travel bans or visa restrictions.

- Sanctions against companies, banks, tax advisers, accountancy and law firms involved in tax deals.

There’s a lot of the line for New Zealand: The EU is its third largest trading partner – with around $20 billion worth of exports every year.

The Government’s also just started the ball rolling negotiating a free trade deal with the EU, which is also at risk of being shelved.

The hardline approach comes from European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs Pierre Moscovici who says there are no exceptions.

So it’s time for NZ to go to panic stations, then? Hardly: another recent publication, from the EU itself, adds some much needed context:

Media reports that the EU is targeting New Zealand for investigation as a tax haven are incorrect and misleading. The EU is currently undertaking an assessment of all non-EU countries with regard to good governance standards on taxation policies. This assessment is not specific to New Zealand, nor has New Zealand been singled out in any way in this assessment.

The assessment will initially consider all non-EU countries, with a first report due in September. At some unspecified later date, the final black list (about which there is already well founded scepticism) will be constructed, taking into consideration:

Only those countries that refuse to comply with international tax good governance standards, or to engage with the EU in addressing concerns raised, will be listed.

The heat is off NZ, for a while yet. Maybe the prospect of EU intervention will quicken the pace of reform, this time, but readers familiar with the glacial pace of the Companies Act reforms (proposed in 2011, delayed and watered down 2011-2014, talking full effect in late 2015), won’t be holding their breath waiting for reform of Foreign Trusts.

While that all grinds along, one waits for NZ to feel in a position to tackle Limited Partnerships, which also have massive potential as vehicles for tax avoidance and money laundering. It’s also high time Look Through Companies, a New Zealand special, cropped up in the news flow. One looks forward glumly to the usual cycle of scandals, denials and capitulation.

Further reading: this is the sixth article in a series about New Zealand’s role in the offshore finance world. Below are headlines from, and links to, the other articles in the series:

Dodgy New Zealand Companies: Mapping Their Global Footprint Since 2009

New Zealand’s Offshore Company Agents: Mossack Fonseca is Far From Alone

Whew! All of that just to avoid paying taxes. I was also intrigued at the section enumerating the ‘legitimate’ reasons for establishing a trust. I would never have guessed that ‘foreign trusts’ could be used to defund foreign despotisms by kneecapping said despots’ tax receipts.

My hat’s off to the authors for managing to keep all of this straight in their heads, and lucidly explaining it to us all.

This post summarises the past ones, but the truth is the media in New Zealand have not covered the issues of trust law and the ‘settlor regime’. Sorry to quibble but referring to just one article in 2012 does not make the question of trusts well known, it was a voice in the wilderness. The writer went from a mainstream newspaper to a business publication which has a paywall, and is also rather right wing by NZ standards. The fact that the trust law changed in 1988, and it took 24 years to get any attention, shows how lame the NZ media are. If it wasn’t for the ICIJ nothing at all would have happened. It also shows that when the Winebox story was broken in the early 1990s it relied entirely on a handful of journalists who weren’t afraid of legal action against them. The ICIJ’s documents remain with journalists who’ve barely scratched the surface of the money laundering problem, mostly because their editors wanted headlines without committing to the time and expertise needed to unravel the years of Panamanian links to NZ, which goes beyond Mossack Fonseca.