By Mike Kimel, a writer for Angry Bear blog. Cross-posted from Angry Bear.

This post looks at the relationship between the top marginal income tax bracket and growth in real GDP per capita (from NIPA table 7.1) in the subsequent year or years.

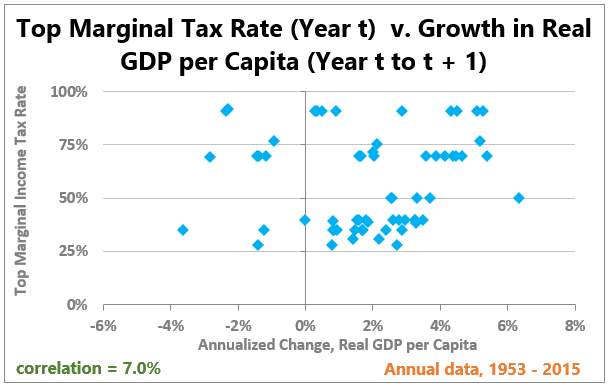

The first graph shows the top marginal income tax rate on a given year along the y axis, and the percent change in real GDP per capita from year that year to the next along the x axis. (Example: tax rate in 1980 v. change in real GDP per capita from 1980 to 1981.) The graph begins at the start of the Eisenhower administration:

Figure 1

Notice the very slight positive correlation between marginal income tax rates in a given year and growth the following year? Perhaps it doesn’t mean that higher marginal tax rates precede faster growth, but it does call into question the idea that lower tax rates are generally responsible for faster economic growth.

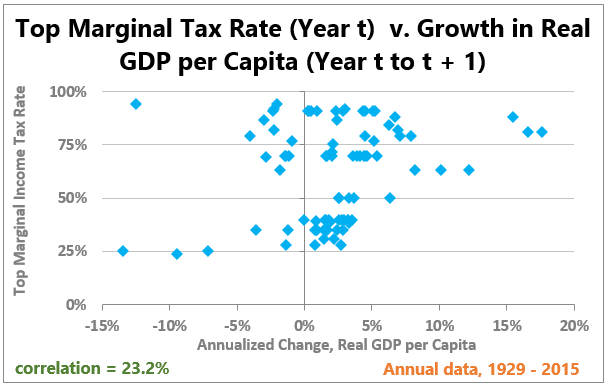

Figure 1 above goes back to 1953 because I felt it makes sense to avoid periods in our history where the economy was very, very different such as the Great Depression, WW II, and the immediate post-war recovery. But the first complaint from those who don’t like what the graph implies will be that I am cherry-picking. To deal with that, here’s Figure 1 going back to 1929, the first year for which reliable data is available (may all thanks be bestowed upon Simon Kuznets):

Figure 2

If anything, the correlation between tax rates and growth in the subsequent year seems stronger when we include the entire data set. In other words, we have less reason to believe that lower taxes lead to faster growth rates than when we started.

Before we go on, a few words about the mechanism which explains the result. I feel like I’ve covered this a million times, but here we go again. If you own a business, you can reduce your tax bill by minimizing the amount of money that gets recognized as taxable income. The easy and legal way to minimize taxable income is to reinvest those sums back into the business. You do that by buying more assets, or by doing more maintenance, or by hiring more people. In other words, you minimize your tax bill by growing your business. In general, the more businesses grow, the more the economy grows. Now ask yourself… are you more likely to avoid taking another dollar out of the business when the tax rate on that marginal dollar is 30%, or when it is 70%? The answer is obvious, except, apparently to most economists and those who listen to them, or else we wouldn’t have so many people who believe something so clearly at odds with the data.

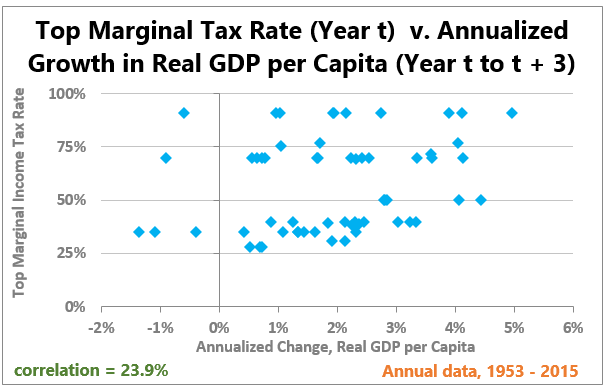

Now… if higher tax rates –> more investing in business, and if investing in business takes a while to have an effect, then tax rates today should affect the economy for more than just the next year. For instance, here’s Figure 1 again, but this time looking at growth in real GDP per capita 3 years out, and not just one.

Figure 3

Notice how the correlation between tax rates in one year, and real growth rates in subsequent years jumps when we go from one year to three years out. I will have a few posts on this topic going forward showing how far out that effect actually goes. (Aargh – that makes three different series I am trying to juggle at the same time!) Let’s just say, as a placeholder, that the effect goes as far out as you’d expect if you really put some thought into it.

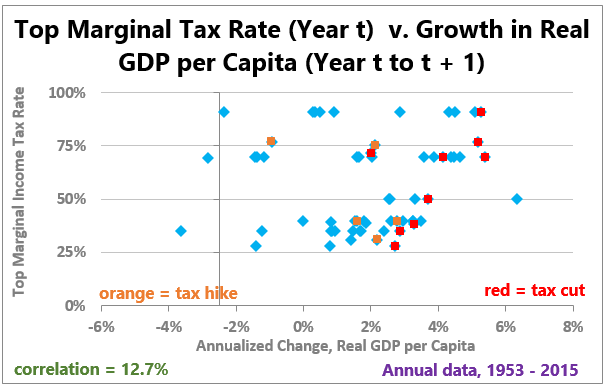

One more thing before I close. I want to briefly show why so many people who believe they have an understanding of economics are certain that lower tax rates lead to more rapid growth. (Even the Democrats seem to concede this. They tend to campaign on higher tax rates due to “fairness” and “fiscal responsibility” rather than growth.) Figure 4 is the same Figure 1, but years in which there was a tax hike are highlighted in orange and years in which there was a tax cut are highlighted in red.

Figure 4

So here’s what seems to happen. As all the graphs have shown, higher tax rates are correlated with faster growth rates in subsequent years. But… years immediately following tax cuts generally do outperform. Thus, it seems that in the very short run, a tax cut can be beneficial, but overall, the economy seems to grow faster when tax rates are higher. Or, as Keynes would put it, you use the tax cut when the economy needs to be goosed, but in normal times, keep the growth rate higher. How much higher, of course, is a question worth considering. Obviously there’s a limit to this – a 100% tax rate is not going to generate any growth at all.

There’s a lot more to cover, including how tax policy goes a long way toward explaining why our economic growth has essentially died. I will have more posts on the topic, but in the meantime, if you want my Excel spreadsheet, drop me a line at my first name dot my last name (that’s mike period kimel – kimel has only one m, thank you very much) and all that is at gmail dot com. I’ve made the spreadsheet interactive. It has a primitive menu allowing you to change the years which are included in the analyses, how many years ahead it looks (in terms of real GDP per capita growth), whether to highlight tax hikes or tax decreases, and how big tax changes have to be in order to be highlighted. The menus are definitely not idiot-proofed but you won’t require much Excel knowledge to play with the data yourself. At least through the next few weeks I’ll be happy to share the spreadsheet. Beyond that, no guarantees.

This is the analogy I use when explaining the effect of top tax rate cuts: The economy responds just like a 7 year old you give a ton of sugar to.

Neoclassical morons saw the sugar rush and claimed it was proof they were right. God damn Say’s law. I wonder how many people have suffered and died in poverty because of that stupid error.

Thank you for the brave (if likely quixotic) attempt to use logic and facts to debunk propaganda.

As the current political environment once again proves, plenty of people will peddle the snake-oil that tax cuts solve all economic problems because that’s what oligarchs want to everyone to believe.

I’m currently reading Les Leopold’s book, Runaway Inequality. A good follow-up to David’s post.

I also recommend David’s book, Chain of Title. Good history of the foreclosure crisis.

Thank you for the interesting graphs. I enjoy them.

It seems to me that not all capital investment is created equal, and this is why, after thirty years of very high marginal tax rates, the US ended up with twenty times the per capita retail space of France.

Malinvestment is a very serious problem. The Japanese kept investing more than they could practically use, and where did it get them? Jimmy Carter had a similar idea with his ‘undistributed profits’ tax.

It may be that the only effect raising marginal rates would have today is to speed the move to robots.

I don’t think we had ZIRP, Obamacare, or tax inversions in 1929 or 1953.

Actually, there’s a hell of a lot of things we didn’t have then but do now. Comparing economies of yesteryear sounds nice as a historical reference, but the era has changed dramatically, especially in technological advances where we simply need fewer humans to produce more.

I would recommend Taxes and the Economy: An Economic Analysis of the Top Tax Rates Since 1945

From the Congressional Research Service, By Thomas L. Hungerford, Specialist in Public Finance

September 14, 2012

Thomas L. Hungerford conclusion was “The evidence does not suggest necessarily a relationship between tax policy with regard to the top tax rates and the size of the economic pie, but there may be a relationship to how the economic pie is sliced.” I take that to mean that the top tax rates do not affect economic growth but does impact income inequality.

The GOP did not care for that study at all, see Non-Partisan Congressional Tax Report Debunks Core Conservative Economic Theory-GOP Suppresses Study

By Rick Ungar, Forbs, November 2, 2012 10:19 AM

“What do you do when the Congressional Research Service, the completely non-partisan arm of the Library of Congress that has been advising Congress—and only Congress—on matters of policy and law for nearly a century, produces a research study that finds absolutely no correlation between the top tax rates and economic growth, thereby destroying a key tenet of conservative economic theory?”

MikeNY,

There will be more tilting at windmills as time permits. I will be doing more posts using what may be more unorthodox ways to look at the data.

Anonymous,

I am not convinced Japan’s problems are due to over investment. My attempt to explain it a few years back:

http://angrybearblog.com/2011/03/japan-post-ww2-rise-1980s-peak-and.html

Northeaster,

The world does change. I think I have a way to tackle that issue in this type of analysis and will try to get to it.

Well, maybe not so obvious as ‘they’ would have us believe.

Actually a top marginal tax rate of 100% would not, of course, dispossess the richest income earner in the country of any and all disposable income to spend or invest. It would only take 100% of that income earned beyond the next lower marginal rate.

Whether or not the 100% top marginal rate would stimulate/retard economic growth depends on what the government does with the money it collects.

If (A) the government were to spend all of that money on real economic investments, like on infrastructure or human capital, and if (B) the money would otherwise have been simply removed from the economy by the super rich person or simply used to bid up prices of already existing assets in secondary markets, the 100% top marginal tax rate would indeed be directly responsible for increased economic growth, all else equal.

Just sayin…

I remember reading an investigative article looking at the tax rates paid by the top 65 corporations. Instead of the 35% tax rate you here constantly complained about, the actual tax rate paid was between 8% and 10%–if they paid any income tax at all!

What the media never says is that the less corporations pay in taxes the more the average citizen pays to make up the difference. Here in Pennsylvania the legislature refused to add a 1% tax on fracking but they did raise cigarette taxes by $2 per pack….

I think there is also the variable for mature industries, that have reached a point where market saturation has been achieved and capital investment and employment is at its apex. Despite factories getting old and worn out and equipment being fried, depreciation is also over, when you have the industrial capacity to build all of the cars people will buy year after year, the higher marginal tax rate will not be used to build a factory to produce another 500,000 cars per year when the existing plants can build the 17 million or so bought by the public. A period when the whole industrial machine just operates yearly without the need for major investments will just see the higher rate as a confiscation when there is not any need for investing the profits for a mature industry operating at full capacity.

Not that we have a whole lot of factories left that this mature state of affairs would apply to. For instance, the only auto assembly plant left in CA is the old Fremont plant that was part of the joint venture of Toyota and GM. GM backed out during its recent bankruptcy and Elon Musk stepped in to use it for Tesla. Curretly, 100,000 cars/yr production. Considering the size and market of CA, you’d think Big Auto would have some sort of presence there, but apparently not. Clearly, Musk does not have to be egged on to invest more money on an Epic scale, but the rest of industrial America, such as GE is another story.

http://www.digitaltrends.com/cars/tesla-fremont-factory-drives-bay-area-manufacturing-growth/

http://www.autoalliance.org/auto-jobs-and-economics/auto-facilities

My question would be, could the higher marginal tax rate accelerate the capital investment on the remaining auto industry located primary in the Mid-west and South. It seems that the move to hybrids by all manufacturers in almost all models will leave the all gas guzzlers in the dust bin of history as the push to go all electric is bridged by the hybrids and the lack of efficiency in operating assemblies for two distinctly different powered cars. This is an enormous investment to change the lines and could be spurred by the higher tax rate. The re-tooling of the auto industry to hybrids and then all electric might need this kick in the butt to get it done much sooner.

Well, GM may have abandoned manufacturing/assembly in California, but, FWIW, I believe it’s among the leaders in the electrification of the automobile. GM, partially anyway, builds its own batteries, while the “Volt” and the “Bolt” (corny a$$ ed names, jeesh! GM’s marketing of these models has been as clumsy as their engineering has been elegant. Makes one wonder if the right hand…) have both represented material advancements in the field.

“The easy and legal way to minimize taxable income is to reinvest those sums back into the business. You do that by buying more assets …”

Whut? Did the author actually ever run a business? When you buy assets, they are depreciated over time — ranging from 4 years for light trucks, to 10 years for office furniture, to 39 years for commercial buildings. A depreciable asset life table:

Depreciation is to accumulate funds for replacing worn-out assets. It’s not a “free money” tax break.

When tax rates are higher, businesses simply have less profit to reinvest. Indeed, when confiscatory taxation gums up the system enough, Big Gov periodically grants special higher limits on Section 179 first-year expensing. Why? Cuz it gives the overburdened economy a “shot in the arm.”

As for claims that the correlation “seems stronger,” why use the old hairy eyeball when you can simply calculate the correlation? Problem is, the number might be disappointingly miniscule. As they say on Planet Japan … “AMAJAA” [“amateur”].

Jim Haygood,

1. The correlations are shown in the graphs.

2. Lifted from the comments at Angry Bear:

That is the really important question on which I did not touch. To be honest, it makes sense in my head, but I struggle to verbalize it. But you asked, so let me give it try.

My wife and I have a small business. (True.) We buy and refurbish dilapidated properties in Northeast Ohio. (Really, these days its almost all my wife and her business partner, but I’m still along for the ride.) Most of those properties are then rented out, but a small number of them get sold.

My wife is really good at it. She has an enviable vacancy rate – usually its precisely zero. Friends of her tenants call her and ask if we anything coming up. This happens regularly. More regularly, in fact, than we are able to find new properties on which we are willing to bid. This business model leads us to double digit returns every year. Of course, we are talking about a modest number of holdings, not a vast empire, but it should fund our retirement when the time comes.

Now, at the end of each year there is usually some money lying around. That gives us two choices: reinvest (say, by buying another unit or moving up the replacement of a roof) or consuming conspicuously / living large. The latter might take the form of going to Europe (my wife has told me its her dream since we were dating). Perhaps we’d buy a Mercedes. Or maybe it would go to my head, and I’d need some bling. Serious bling. Flava flav type bling. I’ve never wanted chains and a grill, but if the cash was just there. OK, it would never happen, but let’s pretend anyway.

Now, if we went to Paris, the money would go to… Paris. The multiplier to the US GDP would be near zero. If we bought a Mercedes, most of the money would go abroad. Again, a near zero multiplier to the US economy. Now, the chains and the grill, on the other hand, well, some of the money might stay here. How much would depend on where the stuff was put together.

On the other hand, say we replace a water heater. Even if it was made abroad, a big part of the expense is the installation. Read that as multiplier to the US economy. If we refurbish a whole house, that’s keeping a crew busy for two weeks to six weeks, depending on the state of the house. That’s a big multiplier.

Besides that, as I said, my wife is really good at what she does. Its good for the economy for her to be here, rebuilding a destroyed house from the ground up, instead of eating cheese in Paris or shopping around for a golden hubcap for me to wear to work. She isn’t any good at shopping for hubcaps.

A relative and some of his friends started a company that is headquartered in NE Ohio.

Three years ago, that company moved into a refurbished building (it had been an abandoned factory) and it’s now thriving. I can personally attest to the fact that the former factory building was built to survive a bombing raid. It is that sturdy.

So, here’s a shout-out to you and your wife, Mike Kimel. NE Ohio has a lot of good, solid buildings that need to be put back to work.

who knew that if you gave business (or the 1%) a big tax cut (essentially giving them a big pay increase for doing nothing) that they wouldnt spend it. and so far most of these tax cuts dont seem to trigger a lot of spending (unless the government sends a check mid year say). and even that doesnt last very long

Thanks very much Mike. High time some empirical evidence is used to illustrate what actually happens with tax cuts. Back in about 2003, I saw a postage sized stamp in Atlantic or Harper’s of the history of the USA’s top marginal tax rate. It intrigued me. Since the USA introduced income taxes back in 1913 with the passage of the 16th Amendment, the TMR has fluctuated wildly, from a low of 7% in 1913 to 94% as the US at the close of WWII and stayed at 91% until 1963, when it was reduced to 70% and the 1980’s when Balance the Budget Stimulate the Economy Ronnie Reagan slashed it all the way to 28%. If tax changes affected the economy, surely with that kind of dramatic swing it would be apparent in changes GDP. When I overlaid GDP over the tax rates, I was amazed to see next to no change let alone correlation. In fact if their was a correlation, the economy grew more post tax increases and was more erratic post tax cuts. So then I asked, if GDP is not significantly impacted by huge tax swings, what else is going on. I then added US National debt and it was immediately apparent. The tax cuts reduced the rate of Revenue collection while Expenditures ticked along modestly at about the rate of inflation but debt soared! Deficit fighter Reagan doubled the US National Debt, that had taken two centuries to reach $1 Trillion, in two terms! The only period in which it fell was after Clinton raised the TMR to 39.6% and the economy had one of its longest periods of positive growth. Bush 41 put the boots to that with his tax cuts and wars and the US debt has soared since then. The Great Recession stimulus continued that spike and the rate of growth in Debt is just starting to decline measurabley. My spreadsheets are all well out of date now, but I’ll send them to you for your perusal. Thanks again for your work and I look forward to seeing your next steps.

THE key variable that usually determines if a tax cut will be followed by economic growth is if government spending is maintained or increased by increased borrowing.

The increase in growth we saw in the 1980’s, for example, was not due to the reductions in tax rates, but was due rather to the increase in government spending (Reagan’s military buildup) financed with borrowed dollars.

Tax cuts are actually contractionary, unless they are ‘paid for’ with increased borrowing. The spending of borrowed money is always expansionary, for it takes money that was removed from the economy by savers and spends it, creating/maintaining jobs.

If, when Reagan slashed the top marginal tax rates, he had actually cut government spending (to ‘pay for his tax cuts’), the economy would have lurched more deeply into a depression.

For many decades now, tax-cut apologists have been able to get away with their specious claims because no reputable economist has pointed out that it is only the spending of borrowed dollars that provides any kind of economic stimulus, and not the tax cuts themselves.

If you look at the isolated effect of a tax cut on the economy—all else equal—it necessarily causes a drop in overall spending (GDP), since the government can’t spend money that it no longer has. If it 1) reduces the total revenues it takes in, and 2) refuses to borrow to maintain spending levels, it has no choice but to reduce spending by the amount of the reduction in tax revenues.

The result is economic contraction, not expansion.

It is only when you combine this one fiscal initiative (the tax cut) with another fiscal initiative that is clearly stimulative (borrowing) that you can then advance the misleading and ultimately false claim that a tax cut can ever produce an economic stimulus.

The actual fact is that tax increases—when they are applied to the highest income earners—automatically produce an economic stimulus.

This, because they enable governments to take money that would otherwise have been removed from the economy by rich savers and spend it, instead. The result: a net increase in GDP.

Thanks James, great commentary. I was just trying to make the point that there is no empirical evidence that I have seen that indicates that tax cuts stimulate the economy on their own. However that myth continues to perpetuate itself by ideological economists and the right. The only Democrats who I’ve heard counter the myth are Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Still awaiting Hillary to take on the issue head on – something I don’t think is in her bones.:))

France recently tried such a ‘soak the rich’ policy, and quickly reversed itself. It did not seem to stimulate the economy at all. There, only 40% of men in the 50 to 65 age cohort work, according to Edward Conand in ‘Unintended Consequences.’ To heck with ‘liberty, equality, and fraternity,’ the national motto should be, ‘tax the rich and support loafers.’

In New Jersey, 1% of residents account for a third of the tax base, so when it’s wealthiest resident, David Tepper, departed for Florida last Fall, the state budget was threatened. California will face the same problems when the current tech boom falters.

Those who forget history are doomed to repeat it.

What happens to the overall economy when you ‘soak the rich’ depends on what happens to overall spending.

If the proceeds of France’s higher marginal rates had been dedicated solely to an increase in overall spending levels re: infrastructure, then there is a zero percent chance of such a fiscal policy not stimulating the economy.

If, on the other hand, the proceeds were used for nothing more than paying off the government’s creditors, almost no stimulus at all would be generated because no increase in spending would occur on the first iteration.

The outcome also depends on what other macroeconomic variables are involved. If the government does, indeed, increase its spending, but other sources of spending drop at the same time, then the overall effect can be muted. But even in this situation, it cannot be argued that increased government spending levels might have failed to provide an economic stimulus.

Take away the government’s increased spending against a secular decline in spending overall and you’d simply end up with a less vibrant economy than you would have had, sans the tax hike.

France, along with other Eurozone and EU nations, are stuck with compliance to Debt/GDP ratios that are acceptable to the ECB etc. A fine austerity mess they’ve got themselves into. So tax revenues coming in have to be used in some portion to reduce this ratio to acceptable levels. Deleveraging is certainly not an investment in growth, but the lifeblood of creditors, who ever holds the debt of France. How much of the soaked rich see their money spent on infrastructure that will immediately reduce unemployment? How much of the soaked rich see their money going right back to them as the holders of French debt?

Good question.

It seems that—perhaps slightly less so in the U.S.—European monetary authorities need to enlighten themselves on how to get the Debt/GDP ratios ‘fixed’ by focusing on directly increasing GDP (via spending increases on public economic investments) as opposed to efforts to reduce the debt in an economy that has quite a bit of slack in it.

Is there some phenomenon that accounts for their steadfast refusal to entertain fiscal alternatives? Are they just obsessed with fighting any fiscal proposals that seem to suggest a redistribution of the pie?

Thanks a lot for this! I’m not nearly as solid in economics as many posters here and while I always had a hunch that it would work like that I never took the time to think about why and it makes perfect sense.

As a small aside, as a person who is not colorblind but has à hard time wiTh close colors, red and orange is a really poor choice of colors to distinguish something, if you reuse the graph I would suggest to use a bigger contrast.

But overall thanks for the great post looking forward to the next one!

Interesting discussion, except that in assuming a 70% tax rate, what is the rate of return on the new investment? In the simplistic example, the assumption is being made that new investments are 1) available, 2) needed and 3) only being made to avoid paying taxes. Very narrow construct to try and prove a point. No mention of rate of return on investment…which taxed at 70% is not going to be attractive for most businesses. Nor at 50%, nor at 35%. Nowhere in these discussions is a realization that a business must achieve a return above their cost of capital. You wonder why capital seeks opportunities elsewhere? Stop the self congratulations and apply the line of logic to almost any industry in this country. Clever – take a smallish local business example that has evolved out of a real estate crash to “verify” the line of reasoning. Clever…assuming a government is smarter at building stuff, creating jobs and allocating tax dollars than you or I. Creating false counter arguments based on past policy mistakes does not prove or verify – such are called straw man arguments for a reason.

Ultimately, good economic policy design is about the incentives created. A certain amount of government needs to be funded, no question. A certain amount of regulations are needed, to keep everything clean and fair, no question. But, there’s a limit and when the cost of governing starts to reduce the incentive to invest in this country because of reduced returns on investment via taxation (or regulation) capital will move elsewhere and growth will disappear. It really is that simple