By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

I’m lifting the term “contingent academic labor” from COCAL (Coalition of Contingent Academic Labor), whose mailing list provides terrific resource for understanding the wages and working conditions of a bewildering variety of non-tenured faculty: Adjuncts, part-timers, grad students, visiting professors, lecturers: Contracted faculty who work semester to semester at the pleasure of their administrators, generally paid on a piecework basis by the course. These terms seem to vary by the institution, and I tend to group all contingent academic labor under the heading of “adjuncts,” because that’s the term my university uses, and I will continue to use that term (as opposed to, say, “temp”). That said, all these workers are members of what Guy Standing has dubbed the precariat, and participate in what others have called the gig economy (a.k.a. the sharing economy, at least for services like Uber[1]). As such, contingent academic labor has a lot in common with contingent labor generally. Gerald Friedman has a fine review:

Growing numbers of Americans no longer hold a regular “job” with a long-term connection to a particular business. Instead, they work “gigs” where they are employed on a particular task or for a defined time, with little more connection to their employer than a consumer has with a particular brand of chips. Borrowed from the music industry, the word “gig” has been applied to all sorts of flexible employment (otherwise referred to as “contingent labor,” “temp labor,” or the “precariat”). Some have praised the rise of the gig economy for freeing workers from the grip of employers’ “internal labor markets,” where career advancement is tied to a particular business instead of competitive bidding between employers. Rather than being driven by worker preferences, however, the rise of the gig economy comes from employers’ drive to lower costs, especially during business downturns. Gig workers experience greater insecurity than workers in traditional jobs and suffer from lack of access to established systems of social insurance.

Special surveys by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 1995, 2001, and 2005, and by the General Accounting Office in 1999, yielded widely varying estimates of the scale of the gig economy. The GAO estimated that as many as 30% of workers were on some type of contingent labor contract, including some categories of workers (self-employed and part-time workers) who are not counted as contingent workers by the BLS. Using the narrower BLS definition, 12% of workers were on contingent contracts in 1999 (similar to the number estimated from more recent surveys).

Higher education has been in the forefront of lowering the quality of work and life for its faculty by turning them into temps[2]; their percentage of contingent labor is far above the national norm:

The number of contingent faculty nationwide has exploded in the past few decades. Since 1975, tenure and tenure-track professors have gone from roughly 45 percent of all teaching staff to less than 30 percent, according to the American Association of University Professors. Part-time faculty and graduate teaching assistants now make up more than 50 percent of the academic labor force.

And exactly as Friedman urges, the universities have engineered this explosion to lower costs (and/or to redistribute revenues. But we’ll get to that). And they do this not for any educational benefit, and certainly not for the benefit of the students. From the (sadly defunct since 2015) Adjunct Commuter Weekly:

And what is behind the resistance of higher education administrators to regularizing and valuing the work of the majority of their instructors? Are there any academic studies that show that underpaid highly trained professional university and college teachers do a better job than those that are well compensated? Are there new results from higher education scholarship that demonstrates that the very faculty who are evaluated on their teaching (as opposed to mainly their research) should be part-time, at-will, temporary parts of their communities, marginalized and encouraged to move-on after a few years of paid-by-the-class piece-work? Have middle-level Deans and other bureaucrats shown that underpaying, disempowering, and churning trained university instructors with advanced degrees and excellent evaluations really does save money and yet keeps instructional quality high? Of course not. There are no such studies. The relentless pressure to keep contingent teachers precarious comes from the short sighted desire of small minded academic officials who want to keep all possible power in their hands.

But that’s unfair. It’s not just power. It’s money, too!

Now, one obvious answer to lousy wages and working conditions is a union, and there’s a good deal of union organizing going on in academia (with many bargaining units seeming to be divided by contract — that is, tenured vs. non-tenured — which rather seems to give away the game before it starts). I’ll list some random recent successes in the Appendix, but for today I’m going to focus on wages and working conditions, and then propose some very simple fixes that university administrators of good will could make, to ameliorate the suffering of their proles temps contingent labor forces. For most of what follows, I’ll rely on the writing of the adjuncts themselves who, being academics, are writing up a storm. (It doesn’t seem to have occurred to our elites that creating an badly exploited class of highly educated professionals isn’t exactly a recipe for regime stability.[3])

Wages

In a word, awful. You surely remember the stories of Walmart workers who are so badly paid that they had to go on welfare? Well, the universities have so arranged matters so that this is true for those who teach our nation’s college students too:

According to an analysis of census data by the University of California–Berkeley’s Center for Labor Research and Education, 25 percent of “part-time college faculty” and their families now receive some sort public assistance, such as Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, food stamps, cash welfare, or the Earned Income Tax Credit. For what it’s worth, that’s not quite so bad as the situation faced by fast-food employees and home health care aids, roughly half of whom get government help. But, in case there were any doubt, an awful lot of Ph.D.s and master’s degree holders are basically working poor.

(What does it say about our society that the people who care for the sick and the elders, who feed us, and who teach our children are treated like garbage? But I digress.)

In fact, conditions are so bad that for many, a $15-an-hour minimum wage would be an improvement:

I am excited to be joining my fellow hard-working Americans at the Fight for $15. I am going not only to advocate economic justice but to serve as a voice for those faculty members who are starting to speak up for themselves. If we all come together, we can finally overcome this battle we have been fighting for centuries.

Finally, let’s consider benefits. In a word, down:

The number of institutions offering health care benefits to part-time faculty and staff members fell four percentage points since last year, to 33 percent. Doctoral institutions were the most likely kind of employer to offer benefits. The drop will likely disappoint adjuncts, who have increasingly been advocating not just for better pay but access to benefits in recent years.

(Of course, this crazy pants incentive structure means that a percentage of adjuncts will feel themselves unable to miss class even if they’re sick, and will transmit whatever they have to their students. Those adjuncts who teach at multiple institutions will put multiple student bodies at risk.)

Working Conditions

Like other adjuncts, who are an ever-larger part of college teaching staff, my colleagues and I don’t have the dignity of an office to prepare course materials, meet students or grade papers. We work in our homes and cars, and meet students in coffee shops or by video chat.

Certainly sending a strong message about the value of an education! In more measured terms:

Respondents said that hiring faculty to more stable positions would reduce stress and enable instructors to better prepare for upcoming courses, according to the report. Many said that undergraduate class sizes were too big for providing opportunities for critical thinking and student engagement, and others said they worried classrooms were poorly laid out for learning. Some wanted private meeting spaces. Others reported wanting more opportunities for professional engagement, as well as more pedagogy and classroom training in their own graduate programs as preparation for teaching. Another concern was a perceived increased need to spend classroom time on remedial work in first-year courses, such as on essay structure.

In other words, the adjuncts simply want the conditions to do their jobs well (something that’s not, apparently, a priority for university administrators). One adjunct, being an academic, went meta and transformed their experience into a parody syllabus, “The Philosophy of Adjuncting”:

Weeks 11-15:

For the last five weeks of the course, class will not meet. Instead, students are required to spend, for each week, eight hours travelling between home and various college campuses. You must write the term paper during these hours while loitering in fast-food chains and uncomfortable public spaces. Bonus points if you can figure out how to connect to the various on- and off-campus wireless networks you encounter. Please email me your grade if/when you do.

Next, I would like to propose some steps that academic administrators can personally take to improve this terrible situation; simple, simple steps that will improve their public relations, don’t involve excess regulation, let alone those pesky unions, and which I hope will be taken in the spirit they are given.

The Modest Proposals

The first proposes better wages, and (as one might expect) the second better working conditions.

The proposal for wages comes from Sarah Wilkinson of Champlain College:

Here’s How We Can Pay Our Adjuncts Better

Turns out, the top 15 executive positions at Champlain College earn a combined $3,967,742, including bonuses. This number doesn’t even count the salaries of deans and other administrative positions. Why does a school of only 2,000 students needs so many vice presidents, deans and provosts anyway? And why are the top 15 alone paid so highly when our adjuncts are paid less than even UVM’s adjuncts, who make $6,600 a class?

I propose that we make salary cuts at the top – for the 15 highest paid executives – spreading that wealth to the bottom, where two-thirds of our professors have been toiling for the same low wage for the last decade.

In 2013, the top 15 executives made a base salary, plus extra compensation. If we take 10 percent of their base salaries and use 100 percent of their bonuses, $1,209,641.60 can be dispersed evenly among our adjuncts.

By adding the college executives’ bonuses and 10 percent of their base salary, 220 adjuncts teaching four classes each over the course of two semesters see their wages increase from $3,300 to $4,674.59 per class, an increase of $1,374.59.

That’s a great start, but what if we took it one step further and deducted another $1,000,000 from the executive salary pool and re-distributed it among adjuncts? That would still leave $1,758,100.40 for 15 executives, which would be $117,206.69 for everyone if split evenly — a perfectly substantial wage.

With that additional $1,000,000, adjunct salaries rise to $5,810.96 per class, an increase of $2,510.96 over their current wage.

The money is already in the budget. To lift our adjuncts up from the bottom of the ladder, it might be necessary for those at the top to take a few steps down.

This seems very simple; it amounts to a demand that well-paid administrators tithe themselves on behalf of the adjuncts they exploit. What could be simpler, or easier to accomplish?

And the second proposal is like it: I propose that the top administrators allow adjuncts to use their offices when they are elsewhere; their offices have windows, WiFi, are quiet, even hushed, have excellent seating and even real desks! What environment could possibly be better for faculty-student interaction? In fact, the truly innovative administration would develop an app for this purpose. When geolocation shows that a Dean is on the golf course, or at a conference hotel, or servicing an important donor off-site, the app would alert nearby adjuncts, and they could schedule their meetings with students in the Dean’s office, or even use the Dean’s WiFi for handling their email, working on their curricula, or sending out grades, or they might even sit in the Dean’s (leather padded) chair for a brief moment of relaxation. Surely it is better to maximize the use of the university’s office facilities for educational purposes, and not simply allow them to lie idle?

Conclusion

Adjunct Commuter Weekly invokes Saint Precaria:

A while ago in Italy contingent workers, all those workers without secure and sustainable employment (almost everyone these days), started carrying around their invented saint, Saint Precaria, a saint for precarious workers. Lecturers, adjunct faculty, part-timers, freeway flyers, the frontline teachers at the universities and colleges of North America now also call on St. Precaria for succor. After all, she is the saint of those fighting for more democracy, justice, to educate the next generations well, and to honor the work of the mind. And above all, she is the saint of those who help themselves.

True, “those who help themselves” are important; I would never disagree with that. But I like to think even though academic administrators have helped themselves — and to heaping portions, I might add — a proper sense of noblesse oblige would lead them to accept the two modest proposals I have outlined here.

Otherwise, how will they live with themselves?

NOTES

[1] Note the class bias in so-called sharing economy usage companies like Uber, Lyft, and AirBnB:

Some 41 percent of Americans with an annual household income of $100,000 or more have used four or more of these services. That’s three times more than households earning less than $30,000 annually, according to the survey.

[2] As usual, I wonder if we have the right rhetoric. I don’t much like “precariat,” although it’s accurate so far as the social relations go, because I don’t see people wishing to self-identify as having precarious lives; an entrepreneur without any capital is a failure by definition, just as a musician is a failure who has no gigs.

[3] Adjuncts of the world unite! You have nothing to lose but your debts!

APPENDIX: Some successes

Champlain College, Burlington, VT, a success for SEIU:

The adjunct faculty and administrators at Champlain College in Burlington have struck a tentative deal in their first contract negotiations.

According to a source close to the talks, the deal as it stands would include a double-digit percentage bump in adjunct pay plus some investment in professional development. The person refused to be publicly identified.

CUNY, New York, NY, a success for the Professional Staff Congress:

94 percent of voting members ratified a new union contract. A record-breaking 72 percent of eligible voters took part in the three-week long ratification vote administered by the American Arbitration Association.

No single contract, especially one in a regime of economic austerity, can end the scandal at the center of American higher education: the reliance on a radically underpaid, precarious workforce for the majority of undergraduate instruction. The CUNY budget, like the budgets of most public colleges and universities, is based on the underpayment of more than half of its teaching workforce. While the provision in our new contract for adjunct job security represents the first crack in the wall of precarious labor, it does not end the system of exploitation, nor does it narrow the gap between full-time and part-time salaries.

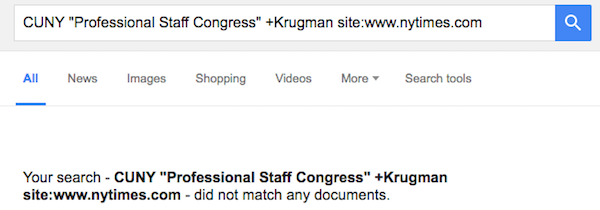

One adjunct comments: “As a CUNY adjunct I’ll make less over my career than my coworker Paul Krugman does in a year.” Oddly:

What’s a bully pulpit for if you don’t use it?

Another example of “the iron law of institutions”.

My modest proposal is to require all administrative hires to undergo extensive psychological testing. Candidates who score low on either empathy or conscience (ie, people who are worrisomely high on the sociopathy scale) are disqualified from employment in any function that has anything remotely to do with human beings.

I’m an adjunct in both the philosophy and economics departments at one of the better community colleges in the country. As you would expect, the working conditions are basically awful, which says something about the conditions in the rest of the community college world. Our adjuncts are also unionized, though. And that such poor pay and poor working conditions (even if both are good relative to many other community colleges) continue despite having a union highlights the severe limitations of unionization for many adjuncts. Not to say people shouldn’t do it, but something more needs to be done. In particular, when you have so many adjuncts teaching at multiple institutions, and the perpetual possibility of classes getting cut at the last minute, the reach of unions is substantially curtailed. What really needs to happen is bargaining units that aren’t tied to one specific institution but to a geographical/metropolitan region. (You could, I think, make a similar argument re: fast food workers.) This could be done in a way that helps ensure, say, a minimum income each year for any adjunct dedicated to teaching, so that they aren’t scrambling to pay bills when a class gets cut, with the possibility of an income beyond that minimum if enrollment levels can sustain it. Obviously this goes well beyond your quite reasonable and welcome proposals, but it’s something that needs more discussion than it’s getting. (Side note: I was part of the Faculty Forward movement being led by the SEIU at first, which I still support, but got alienated by their lack of long-term thinking and almost total ignoring of non-four-year institutions.)

That’s a really good idea. I deliberately stayed away from the nuts and bolts of organizing, because I know very little about it.

Further discussion most welcome!

I think most of the unions that are trying to organize on campuses (I know this at least consists of SEIU, AFT, UAW, USW and maybe NEA and UE) want to have a so-called hiring hall model. The basic premise is that you need to organize all of the adjuncts in a metro area since most adjuncts teach at more than one place. This model has not been fully implemented in any cities as far as I know, although I know of several cities where it is in the works. This is really the only way to get sustained increases in pay and benefits over the course of years, since if only one school is unionized and getting regular salary increases, eventually the admins can (justifiably) say that the pay at the unionized school is much higher than other schools in the region and call for a wage freeze until the other schools catch up, which will be never. One problem that has already been encountered with this strategy is that there are several unions that want to implement it, sometimes in the same city. This had lead to competing unionization drives at some schools, which hurts both the unions and the adjuncts, and at least one high level agreement (that I know of) between different unions over who gets what turf.

The nuts and bolts organizing is really where all the action is, but there is no way to know about it unless you are involved somehow.

Having been somewhat involved in the early stages of Faculty Forward, which is an SEIU campaign, I never heard anything like what we’re talking about here. The union which I’m currently a member of is part of NEA, and again I’ve never anything either from them or my own union leadership about this idea. (To give some context, I teach in the Chicago area.) However, if it’s being seriously discussed elsewhere, I’d love to hear more details.

Interesting. That strategy seems to be what’s happening in my neck of the woods. Though it’s all SEIU from what I can tell. I don’t know if it was SEIU’s internal strategy, or local universities were ripe for whichever union put time into courting the adjuncts.

Regional organizing is going on in areas, such as Pittsburgh and NE Ohio, as well as successfully done in the DC area. It’s the way to keep universities in the area from colluding to keep wages low. Thanks for the article and the imbedded links. Very useful.

It is good to see this proposal put out by someone with “on-the-ground” experience with the deficits of current organizing. Below is an excerpt from a recent essay:

“In terms of strategy, however, the precariat needs to gain control of labor just as the industrial workers intended to do by forming labor unions. (That promise was betrayed by union leaders who pursued “business unionism” and upended by capitalists who globalized the workforce in a race to the bottom.) Today, gaining control of labor may be accomplished by adopting a version of the old union practice of hiring halls. The building trades still have these, as do some hotel worker unions. And this is the strategy of work centers where hiring takes place under the supervision of the workforce. A new strategy to seize privatized platforms like Uber and Mechanical Turk by cooperative structures follows this same course – the workforce controls the job assignments by controlling the platform.”

From “An Agenda for a Politics of Time”

Excellent article! By way of ENFORCING these reforms, I’d suggest this:

Any university that takes any government money must be required to publish a pie chart of where every penny of their money goes (how much to adjuncts, to faculty, to janitors, to administrators, to the sports teams). So students and the parents of students could compare all colleges side by side, forcing them to compete on cutting wastes.

I can’t think of a way to fit ‘donations’ and ‘grants’ from the military, Exxon, Mosanto, etc, into the pie-chart, although some of us might like to know that information as well.

That’s a great idea. Transparency. About both where the money comes from (including research grants) and where the money goes.

Love the idea of the top administrators giving up their offices to adjuncts.

Two things driving down wages from my perspective:

Graduate students teaching:

Why pay someone with a doctorate to adjunct when you can have your graduate student do it for their stipend (1500/month back in the late 2000s when I was in grad school)? My humanities undergraduate work at a private IHE involved not one, not two, but three classes taught by PhD students. Not just 101 courses, mind you, but things in my junior year. Graduate students are cheap, expendable, and have less labor protections.

Students as employees but exempted from all kinds of DOL rules:

As a college administrator involved with student pay, I’ve looked many times at the Department of Labor’s rules with regard to student labor. It’s pretty dismal. Students can be paid less than minimium wage: https://www.dol.gov/whd/minwage/q-a.htm

Here’s the big secret: go into departments employing students. Chances are, the students are paid a “stipend” (without an accompanying contract, mind you) that is fixed. But they are probably working more than 20 hours a week. Research labs in particular are notorious for this. Some students treated, more or less, as administrative assistants for departments. Why wouldn’t they? Their professors are responsible for their grades.

One other thing I forgot, students as IHE employees is very peculiar, because they can act as admin assistants in a variety of settings, however according to most internal policies, they are not agents of the institution. Good universities clean up this issue with a contract, confidentiality agreement, what have you. But if that student is answering the phone, you damn sure better believe that they are now an agent of the university, IMO.

On the other hand, these student jobs were one of the things that really bailed me out in my academic career. Double edged sword.

What is IHE? I couldn’t find an explanation here or elsewhere.

The colleges using students as free labor issue may have gotten worse, but some of these issues go back 60 years or more. Maybe they weren’t used so much for teaching faculty then (there were more real tenured professors) but they WERE used for cheap research assistants, which the schools would play games with to delay graduation to keep the cheap labor going, I’ve heard the stories. Therefore I think it was to some degree always thus in academia (ie there were no “good old days”), but it does seem to have gotten worse.

I think there’s probably data out there on this phenomenon, but I don’t have the capacity to parse it out. If someone can, it would probably help frame that part of the discussion.

Really? You “don’t have the capacity to parse it out“? Can you be more direct?

Anecdotally this is very common (I can remember one program that graduated two Ph.D.s in the space of 10 years, who took 9 and 12 years respectively to complete). Even in the programs with a reasonable reputation where you can graduate in a normal span of time, teaching university level classes for less than minimum wage always felt exploitative. Teaching quality (never a high priority at most institutions in the first place) can also suffer – more than once I can recall students being assigned to teach a class on a subject they didn’t know anything about, because “it will help you learn it.”

They get away with it because grad students are a captive audience (you can change programs to get away from the sweatshops, but you are still stuck in the graduate education sector in general) and because the faculty often have little to no interest in teaching either. I had a friend who wanted to make a career out of teaching at tertiary level and who volunteered to run a course – defining the lecture content, writing and grading exams, the whole works. A large number of his students described him as “the best professor they had ever had.” With no training and minimal experience, simply having a natural interest in and aptitude for the profession and being willing to put in the work to do it properly were enough to move him to the top of the heap. That’s how low the bar was. And this was at a reputable program at an Ivy League institution (actually the Ivies are the worst for this – less well-known schools actually have to do a decent job of teaching in order to compete).

Grad students aren’t always cheaper. Where grad students are unionized they quite often have good or at least decent benefits with pay that is commensurate to the lowest tier of lecturers/adjuncts, who receive no such benefits. This means in certain cases contingent faculty can actually be cheaper, and the one group is quite often played against the other. It was a cause for concern at Michigan, before the lecturers unionized, and still is at Iowa, where the grad student union was told in their most recent negotiation cycle that they are “pricing themselves out of the market.”

Grad students also have time limitations and are a strain on resources in ways that adjuncts are not. They’re also far less disposable. An adjunct can simply not get their contract renewed, whereas schools typically make longer term commitments to grad students in order to see that their education is paid for. Also, when there are massive enrollment increases, as there were at my school this year, you can’t just suddenly take on another dozen or so grad students in each department.

I would like to report another success story (mostly), my own institution, Evergreen State College, where adjuncts make 90% of the corresponding faculty salary. (All faculty, regardless of fields, are on the same salary grid, where what you make depends only on the number of years of experience.) The difference is justified by less expectation of governance, although there are no restrictions on adjunct participation and many have been very active (including faculty president). As administrators here point out, replacing a continuing faculty with an adjunct is not, in general, a way to reduce costs, since the adjunct may well be paid more.

During recent years, as a result of collective bargaining, there has been an effort to give as many adjuncts as possible multi-year contracts. Ultimately, the only reason Evergreen has adjuncts at all is to provide extra flexibility. It has nothing to do with cost reduction.

The one area where I think adjuncts could be better served is offices. All of them have offices, but often they must share. It would be great if we had parity on this front. But that gets into space constraints.

Careful attention needs to be paid to the big time sports teams. Even many high profile programs are a big drag on university budgets, but these costs are often hidden. Stadium maintenance can be mixed in with routine building and grounds. Some defend these programs on the grounds they attract money to the university, but usually the money just goes to the football or basketball program. These schools compete for the high profile athlete and pass the costs along tot the other members of the community.

It seems like the higher education system is as messed up and corrupt as the health care system. In the same way that the ObamaCare debacle, besides being interesting in its own right, is a good vantage point for the health of the system, I’m looking at the treatment of adjuncts with the hope that can play the same role.

Clearly, it’s not just administrators, though administrative bloat is important (and provides “good jobs at good wages” for the 10%.

Big time sports is one area, as you suggest, and another one would be construction, much of which has nothing to do with education. Other areas would be “star” professors. Another one might be naming rights and the roles of boosters and donors generally.

When you remember that the pre-Reagan University of California guaranteed an education at free or low cost, and to a world-class institution (granted, on merit) it just makes you want to weep.

When you look at the highest paid state employee in every state, it is usually the coach of the football team at the state university. Occasionally it is the dean of the medical school. $2 million/year seems to be the entry level wage for football coaches in the Big-10. Of course the “revenue” sports claim to be self supporting but I am sure if you looked at the details, they takes resources away from the academic side. Intercollegiate football is really just a minor league farm system for the NFL. Who needs them?

I remember a great James toback/Milos forman film,the gambler, that left me with the impression that sports,besides the mainline graft, was there for underground betting industry.

Did my PhD in political science and have adjuncted since 2004 (when I was a grad student), and did a year’s stint as a Visiting Prof, too.

The proposals are decent, but I’d add:

– same-level pay for adjuncts as full-time, tenure-track profs. This has to be the same demand as eliminating tiered wages in other labor negotiations.

– multi-year contracts, but a minimum of a two-semester deal. The one-semester gig has to be eliminated except for emergencies (someone takes another job in the middle of the summer, gets ill, etc.). The difference between knowing you have two semesters and being forced to run a treadmill looking for spring work as soon as you secure fall is staggering.

– in the long run, there has to be a reduction in the amount of courses taught by contingent faculty due to hiring of more tenure-track lines. There should be a ratio cap (75-25?) that favors tenure-lines to contingent.

– grad students need experience but they shouldn’t be used as temp workers/low wage replacements to prevent wage rises for contingent faculty. Allowing grad students to teach discussion sections while being given at most 2 classes to teach until they finish their degree makes sense. This would mean increasing the years & amount of their stipend.

PhD 2000 History; also of the precariat most of the time since. Agree with most of what you offered but would add: per-course pay for adjuncts needs to be HIGHER than regular profs. First, for reasons of equity: there are many other forms of compensation that the regular faculty enjoy and adjuncts do not. Some are externalized costs of regular instructors – e.g. an office in which to store one’s books (most of us own many hundreds after a decade or two of working). No, my office in in my house – a “spare” bedroom, which we had to add to the cost of our home. Not enough to give me an office on campus, either – not if I also have to travel odd days to another university to teach there, etc.

The second reason is because the inequity is institutional. To get rid of it necessitates changing the underlying factors that led to the creation of the institution. Making adjuncts MORE expensive than regular profs creates a market incentive to DO SOCIAL GOOD and eliminates the perverse incentive to inflict social harm. It gives university admins a reason to think more carefully about enrollment, course offerings, hiring practices, etc. Above all it gives them an incentive to move adjuncts onto the tenure track.

Personally I would like to see that as a law: businesses of all sorts, from Wal-Marts to universities, could be penalized for “underemployment” – waste – of human resources – just as they are penalized for toxic waste, etc. The penalty should be such that it universally renders temp employees more expensive, hour per hour, than full time. “Flexible” business practices are fine — but NOT if the costs of those practices must be borne by the human flesh and blood of exploited workers.

And to generalize again: a principle aim of our economic policy should always be to do social good rather than harm. It would be nice if those fancy economics schools could actually direct some of that brain power they have to identifying perverse incentives and developing plans to curtail and eliminate them. You know, “economics as if people mattered”.

Bonuses?

Bonuses?

What does one get a bonus for at an educational institution? If a faculty member wins a Nobel Prize? Bonuses are based on profits: So what does the existence of a bonus structure say about the institution?

This is still another instance of the idea that everything should be run as badly as U.S. businesses are.

Welcome to the new U.

Presidential Perks [InsideHigherEd]

When did USN&WR start ranking universities and colleges? When did they dictate the metrics for what higher education (“successful businesses”) ought to look like?

Just googled it:

1983.

Bingo! US News has been a hugely toxic force in American education, in my opinion. For one critical and germane thing, doesn’t USNWR count size of endowment relative to enrollment as a very important thing in the financial resources factor? And doesn’t that mean there is (1) an endowment arms race, with huge amounts of money, light-years more than any genuine need including any conceivable contingency planning, being socked away solely for bragging rights about the size of one’s, er, endowment; and (2) a perverse incentive to hire more administrators by slicing and dicing duties into infinity as another method of enhancing the school’s financial resources ranking (and as a way to keep pushing the top executives’ compensation upwards as the scale and the appropriate distance between ranks become more complicated?

Does Harvard really need a $36 billion endowment, i.e., $1.7 million per enrolled student, approximately $17 million per faculty member? And why would it need 17% of its faculty to be part-time with these kinds of resources?

It’s good that academia is joining the fight for $15. A decent wage should not be contingent on a college education and a college education should be attainable for anyone who wishes it.

I recently made a visit to my local representative after my third child was transported via ambulance for a “panic attack” after finishing a shift(several of the co workers walked out because they had no break and the manager was absent from actually managing.) We have laws that outline breaks and lunches for minors but nothing to prevent an employer from taking advantage of a 19 year old and require them to give time to eat and rest when you schedule for a 13 hour day. These are entry level positions so essentially the people running these establishments ought to be teaching workers good habits not exploiting them and our government should be aiding them in doing this if they aren’t willing to do it of their own accord. (I also had the same conversation with McDonalds saying that instead of having their employees walkout it make much better sense to schedule people their breaks into the shift.)

Working conditions are hard all over folks.

Thank You! Its as if people who work with their hands and minds don’t exist.

Nobody gave a crap 30 years ago when this all started.

I know, if you didn’t get a degree you just don’t matter. Elitism.

How can that be? The Fair Labor Standards Act used to mandate that full-time workers had a paid half-hour minimum lunch break (no interruptions) and two unpaid fifteen-minute breaks, as well as comp time or time-and-a-half overtime pay for time over 40 hours a week. Does someone scheduled for a 13-hour day not have enough weekly hours to qualify as full-time? Has the law changed since the days when I cared so much I kept track? Or are employers just thumbing their nose at the law while the NLRB ignores them?

This is a great piece: “a proper sense of noblesse oblige would lead them to accept the two modest proposals I have outlined here. Otherwise, how will they live with themselves?”

One can only ponder this, one of life’s grotesque mysteries. The term “adjunct” always struck me as pejorative. It is not a noun; it’s not something one can be. It means, “something added on, but not part of the whole.” That is not a job title. We don’t call assistant professors, “Assistants'” or full professors, “Fulls.” I think it’s often a put-down. And I’d like to add that there is a particular pool of exploited teachers who come out of arts programs and are, as practicing (i.e. full-time) artists, very exploitable by this system.

My wife is an adjunct at a local community college here. Being unionized has helped, but I still tease her, saying “she would make more per hour if she was flipping burgers at McDonalds”.

Oh, and now she’s considered “Fully Employed” even with only one class. Makes 1/4 of what she did when she was an engineer before her company’s manufacturing was sent to China.

This piece is a welcome addition to the work of the movement to preserve quality higher education and to preserve the integrity of the profession of college teaching. Please also check out the work of New Faculty Majority, which grew out of COCAL and since 2009 has been a major factor in the increased attention being paid to adjunct working conditions, including by media, unions, and the federal government. (Representing NFM, I testified before Congress in 2013). The metro strategy for adjunct organizing discussed above was laid out by Joe Berry in his book Reclaiming the Ivory Tower. SEIU Local 500 in Washington DC is pioneering this strategy and other unions are taking it up as well. Organizing is not just about unionizing — collective and collaborative action is necessary to reverse the tide of precarious employment in higher ed and across the economy. http://www.newfacultymajority.org

I am glad for the geographical emphasis of the comments. I continue to fill out surveys and deal with administrations at the universities where I work that seem completely oblivious to the fact that most adjuncts are employed at more than one school. The model of a unionizing a “shop” is completely obsolete in this instance: it would best be a region that is unionized.

Second, I have two MAs and have completed coursework, long ago, for a doctorate, but more to the point, just published a well received scholarly book, regularly publish scholarly articles and go to conferences, at my own expense, of course. Yet completing my PhD at this point means repeating a lot of pointless coursework. I can’t afford it (I am actually willing to do it if I could afford it, but am older and unwilling to go into debt.) The point is that I am trapped. Nothing matters but the PhD, and yet, as an adjunct, there is no reasonable way I have found to get it, which means I can never be more than an adjunct. A big part of reform is offering adjuncts a way up: paid education as a benefit, maybe paid book leaves. But I dream.

Great idea that institutions should develop creative ways to make it possible for adjuncts to finish their nearly-complete PhDs w/o having to pay for their education twice.

Kent State University began organizing in Spring 2016. We’re about 51% of the faculty and do not have one spot on the Faculty Senate, kind of like a crazy uncle in the attic that is not talked about. We have a lot of work ahead of us if we are to bring part-time faculty a bit of dignity and economic fairness.

The increasing use of adjuncts has been going on for decades now, and I view it as another aspect of the so-called “hollowing out” of the middle class, comparable to the destruction of industrial production jobs, the precipitous decline in entry-level positions for new lawyers (with document review moving to Asia and the computer), and public employees no longer being able to afford to live anywhere near the cities whose residents they serve (cf. San Francisco, which is starting its academic year 600 teachers short, because salaries no longer enable teachers to live near SF).

What will happen when no one can any longer afford to become a teacher, an adjunct professor, or even a lawyer? Will any middle-class professional or skilled production jobs even remain? What will happen when there are no jobs apart from minimum-wage jobs? Who will foot the bill for Medicaid and SNAP, for infrastructure maintenance, for public investment of any sort – who will comprise the U.S. tax base? And if the U.S. is ultimately a post-industrial, exclusively service-based economy, who will pay for these “services”? One percent – or five percent – of the population will be supporting the other 95 percent through the purchase of services?

I spent nearly thirty years in higher education at an American institution abroad, starting as an adjunct and progressing to regular faculty and then administration. Being an adjunct was indescribably stressful – never knowing whether you’d have the sections you’d been scheduled for, having no long-term job security, being compelled to spend all your time preparing for class, teaching (I taught four-five sections a semester) and marking papers, with no time for professional development – research and writing.

Question for U.S. adjuncts: Are you eligible for TIAA-CREF, or on SS?

“What will happen when…” No need to ask, the answer is already before us – in Flint, in Ferguson, in Detroit, in New Orleans, in Cleveland. After being deprived of their jobs, the people of these and other American cities have been gradually and systematically deprived of their [rights of] citizenship and their humanity – so that we may now lock them up (or shoot them down) with impunity. Nor is it only Black and Brown people who have been so affected: look at the economic and social devastation of Appalachia, especially in KY and WV – among other places.

Graduate students being paid to teach is so old school. Why pay anyone when you can charge them?

My university is way ahead: make teaching part of a student “education”. This way graduate students don’t have to be paid a cent. In my university, labs get money from NIH to pay graduate student stipends and tuition, and the university uses these students to teach. Thus, no need for adjuncts, and no need for faculty who can’t get grants from NIH. Even better, these money’s generate indirects! So an extra 70% to the university for handling the gig.