This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 205 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in the financial realm. Please join us and participate via our donation page, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our initial target, tech infrastructure

Yves here. This post is important because a vocal contingent of economists bitterly opposed the idea of extending unemployment insurance during the worst of the post crisis period. The claim was that the longer employment insurance term would lead the unemployed to become dilatory about their search and/or too fussy about what was on offer.

By Christopher Boone, Assistant Professor, Cornell University; Arindrajit Dube Research Economist, University of Massachusetts, Amherst; Lucas Goodman, PhD Student, University of Maryland; and Ethan Kaplan, Assistant Professor of Economics, Stockholm University. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

As joblessness soared during the Great Recession, one of the key policies enacted by Congress was to extend unemployment insurance (UI) duration. The change was dramatic: Prior to the recession, all but two states provided a maximum of 26 weeks of benefits. During the recession, however, most states reached a maximum duration of 99 weeks. Economists have long been concerned about the possible negative effects of extended benefits in reducing job search and thus the level of employment, while simultaneously recognizing the social insurance value of unemployment benefits.

Whereas a substantial body of literature in economics has estimated the impact of UI generosity on individual employment, the literature on aggregate-employment effects is small and fairly recent.

What is the difference between the individual and the aggregate effect of UI on employment?

One difference is aggregate demand. In addition to dis-incentivizing workers from searching for employment, UI also provides liquidity to workers who are well below their usual income levels, likely liquidity-constrained and therefore very likely to finance their consumption out of their UI earnings. This may have a positive impact on economic activity in general and on employment in particular, even if UI disincentivizes workers from searching for new jobs. On the other hand, there are some concerns that more generous UI benefit could raise workers’ reservation wages, which in turn could lead employers to cut back on vacancies and job creation.

Unfortunately, the nature of the UI extensions during the Great Recession makes it difficult to estimate the aggregate employment effect. The benefit-extension programs were structured to grant longer benefit lengths to states with higher unemployment rates, leading to a reverse causality problem.

To avoid this estimation problem, we examined 1,161 county pairs that straddle state borders. Within each pair, counties share a similar geography and economic environment, but often had different maximum lengths of benefits. In other words, these county pairs provided good controls for one another while receiving differential treatment. We then compared changes in county employment to changes in the maximum length of benefits within each pair for the 2007-2014 time period.

So what do we find?

First and most importantly, we find no disemployment effect from the UI benefits as measured by the employment-to-population ratio. Our estimates suggest that, at worst, increasing UI duration from 26 to 99 weeks led to a 0.09 percentage point decline in the employment-to-population ratio, and at best had the effect of boosting this ratio by 0.41 percentage points. Given the fact that this was a massive increase in benefits (almost quadrupling the pre-recessionary level of UI duration), it suggests that the concerns about disincentivizing job-search efforts may be overblown. Our estimates are consistent with modest reductions in labor supply as found in some micro-based estimates from the Great Recession, coupled with a moderate-sized aggregate demand effect from increased local spending. The findings also suggest that, at the price of $50 billion per year, the federal government was able to provide substantially more generous income support for hard hit households without constraining economic recovery.

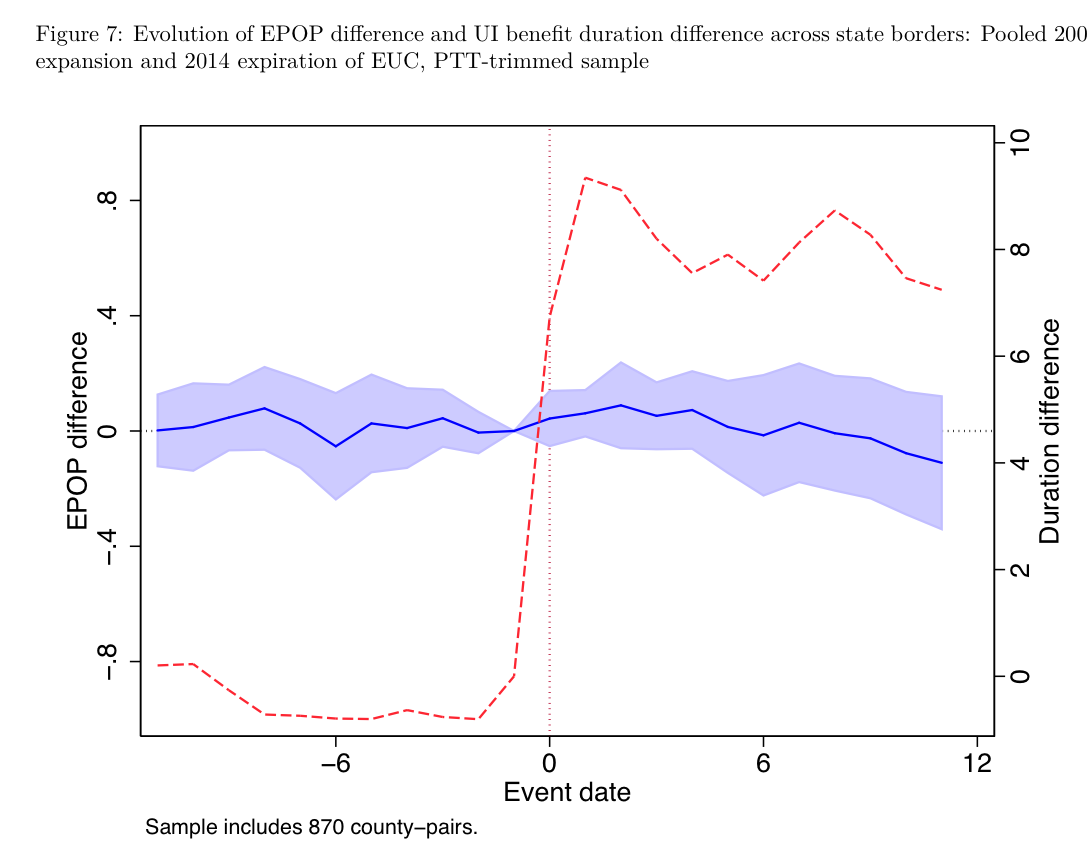

These findings are summarized in the following figure, which plots the employment response to national level policy changes, namely the 2008 expansion and the 2014 expiration of the UEC. When the policy change occurs at event date 0, there is a clear increase of around 10 weeks additional benefits in one side of the border as compared to the other, and this change is quite persistent. In contrast, employment appears to remain largely unchanged over the following 12 months.

Our findings have important policy implications in the event of another deep recession. Policymakers should keep in mind that extending policy benefits is likely to entail a very small effect on aggregate employment, even as the social-insurance value of extending benefits to those who lost jobs is likely to be large.

How about a few comments about economics.

1. There is a very little being done to educate children about economics. I have even had high school students ask me how to write a check.. . .and then use the information it contains.

2. Far too many parents are now too distant from the negative effects of depression. Others are so traumatized that they give (yes, GIVE!) incredible amounts to their children as “allowances”, subsidize automobile cost, insurance, etc.

3. Shortly after World War II, a good executive salary (the top guy) was five to eight times the median salary paid to the workers. The last published figures I have seen is a median CEO salary of 350 to 500 times the median “worker bee” salary (which is calculated including benefits).

4. The rise in State Lotteries which started in New Hampshire in the 1960’s is a testimony to the disappearance of the possibility of earning a decent wage and planning for a reasonable future including the education of our children, the ability to own a reasonable home, the ability to support a family without having to have both members of a stable married relationship work for wages, and many other aspects. Few economists call a lottery what it actually is, an added tax for the lower paid, which in Maine has been studied and demonstrated who is actually buying lottery tickets (hint, is is not those who earn substantial paychecks).

5. A good place to start might be in a wholesale rewriting of the public school economics courses into “common language” (as opposed to “economic jargon”), and the requirement that every school that wishes to grant diplomas to 95% of those completing the 12th grade and are not doing so this year be required to place economics at the same level of “reading, writing, arithmetic, and history”.

6. Personally, I have investigated communication quite a bit and in 12 years of work have never discovered a single one that included any value from the use of “um”, ahh, well, and so forth.

Good luck.

John S. H. Carter, Ph.D.

Another punitive doctrine, to punish those who lose their jobs due to the decisions of business to cut back one of the most immediate line items on their budget that it controls. In an economic downturn, slackening demand, without the negotiations to squeeze suppliers, or firing up the lobbying machine to cut taxes, get sweetheart government contract revenue, obtain a difficult act of congress, the path of least resistance turns employees over to the unemployment department of the states.

And of course, the paltry sums of cash that come into the hands of the downsized are little more than pass through payments that temporarily reside in direct deposit bank accounts before they are turned over for rent, mortgage, car loans, keeping the lights and heat on and oh yeah, eating some food. Maybe the cable can get turned back on or maybe the cell phone can get turned back on and hopefully your marriage and/or family will survive more or less intact.

The money that is immediately spent back into the economy is in fact more of business subsidy, as it does not serve as some sort of windfall that can be stashed away for the uncertain future. Plans for the future mean little when your are out of work living 24 hours at time.

What is clear to see from the politicians who stand up and denounce the slackers who want something for nothing when they demand better social insurance programs that do more to keep a standard of living from going over a cliff to crash on the rocks is a type of political control. It is hard to tease out the political value from the economic need to prop up the economic demand that falls further with the death spiral of more downsizing and fewer paychecks being passed out. The money from the government that replaces the money from lost paychecks is obviously interchangeable. Due to the famous fungibility of money, what difference does it make if the needed spending that supports demand from further contraction comes from the public or the private sector, as long as it keeps coming to support the citizenry in their hour of need and supports the larger economy as a whole from further damaging downward momentum.

Here is another contribution, of cash as well as thoughts. Keep up the good work. Your investigation into Calpers is echoing into the political hallways of many states, including here in PA. The smarter the political activists are, the smarter the elected officials are about pensions, investments and financial dead ends the better we all are. It can’t happen without your site and writing, we would be as clueless and bereft of valid financial info, dependent upon the battalions of propaganda artists from the Manhattan and Mercatus Institutes inter alia, as they fan out across the nation’s local editorial pages and web sites, poisoning the well of public discourse with lies.

So when robots are doing most of the needed labor shall most of us receive permanent unemployment benefits and the future will have arrived at last?

I believe people are going to find work of some kind to do, maybe work that produces so little profit that it’s not worthwhile to build robots to do, but still can give a sense of satisfaction for doing something well.

Yes, people do find work rewarding if they are free to do it as they see fit.

Actually, people prefer to deal with people so there will always be a need for human workers in that regard.

But we also like to deal with happy people which implies that such workers be there because they want to be there – not because they must be there to earn an income. That implies a Universal Basic Income so that work can be what it used to be – largely voluntary – before the banks and the so-called creditworthy stole the commons and family farms, industries and business.

From my reading of history I don’t believe the feudal serfs worked the land because they wanted to be there — otherwise there would not have been laws punishing them for leaving. Maybe if you go back earlier than the small yeoman farmers of the Roman Republic or the slave-owning citizen farmers of the Greek city-states, but I don’t think living conditions were all that great for barley farmers in the Euphrates valley in the Hurrian Empire. I think even hunter-gatherers did not get so much pleasure from their hunting that they were doing it for sheer joy. Your point about the theft of the commons is good, though. It was done purposely to drive peasants into the factories.

I think even hunter-gatherers did not get so much pleasure from their hunting that they were doing it for sheer joy. Procopius

I read 20 hours a week would suffice. Granted that lifestyle might not support a large population but my point is not against economies of scale but that they be ethically financed.

Question: Without this extension of the UI time limits how many more foreclosures would there have been, how many more homes/lives sacrificed on the bloody altar of neoliberalism ?

Since the Obama stimulus program was (as was known at the time) far too feeble the UI extension may have been all that stopped the Great Recession turning into Great Depression 2.0. I’ve long had the feeling that a full bore Depression was much much closer than we here at NC think even now … let alone the starry-eyed Bernankes of this world.

The economists who oppose unemployment insurance are probably people who grew up in upper middle class homes and have never had occasion to do any physical labor in their lives. They probably got their first jobs through a network of family friends or their school, and have been promoted since then because they are social friends with their superiors. In “The Coming of the New Deal,” (vol. 2 of his Age of Roosevelt trilogy), Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., points out that Roosevelt, Harry Hopkins, and other creators of the New Deal, understood that what unemployed people wanted was not merely money to buy food (yeah, they did want that), but a chance to work. People wept for joy that they were able to get a place in the Civil Works Administration (later the Public Works Administration). The people who claim that only the threat of imminent starvation will force people to work are displaying their hatred and contempt of working people. People hate being “on the dole.” Ask Dr. Ben Carson.