Lambert here: The Treasury view?

By Ian Tomb, Emerging Markets economist, Goldman Sachs, and Kamakshya Trivedi, Chief Emerging Markets Macro Strategist, Goldman Sachs. Originally published at VoxEU.

Over the past five years, global trade growth has been stagnant. With protectionist sentiment intensifying across advanced economies and China and other emerging markets (EMs) appearing to pivot away from export-oriented growth strategies that had incentivised the creation of global supply chains in the 2000s, a hypothesis informally known as ‘peak trade’ has become increasingly popular (Economist 2014). According to this view, the current trade stagnation is not temporary, but instead reflects fundamental changes to the global economy. In the coming decades, these changes will prevent growth in global trade from outpacing growth in global GDP, as it has since World War II. If true, this idea has profound implications. It implies a stoppage, or even a rolling back, of many of the core benefits and costs that have come to define the globalised world, including increased gains from trade, cross-border financial flows and geopolitical interdependence.

Our analysis (Tomb and Trivedi 2016), which we outline here, counters this view. Using a variety of approaches, together with data that allows us to track the paths of nearly 400,000 trade flows over the past 20 years, we push back against three primary variants of the peak trade argument.

Peak trade view #1: A falling ‘trade beta’

First, many economists note that the measured sensitivity of trade growth to income (or GDP) growth has declined in recent years (for example, Escaith and Miroudot 2015). This ‘trade beta’ has fallen from above 2 to near, and even below, 1, the value at which trade simply keeps up with income. Our work suggests, however, that the trade beta—not a clearly-defined structural parameter, and difficult to estimate without bias—may not reliably represent the actual (causal) effect of income growth on trade growth. Shifts in different countries’ relative GDP growth rates, for example, can distort the trade beta in standard cross-country models, creating the impression that income is having a larger or smaller influence on trade.

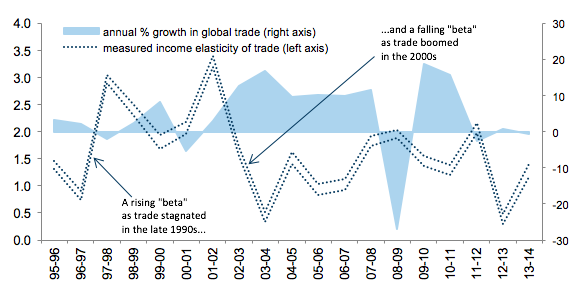

More generally, the trade beta is not a sufficient statistic for the evolution of global trade. Shifts in the measured trade beta sometimes sit awkwardly with the broader global trade picture. For example, Figure 1 shows that the trade beta—estimated using a standard ‘gravity equation’—declined sharply in the early 2000s, a period of historically rapid trade growth. Moreover, estimating the trade beta with our detailed data set reveals year-to-year changes that are too volatile—including in recent years—to plausibly reflect shifts in meaningful economic relationships.

Figure 1 Shifts in the ‘trade beta’ fit awkwardly with shifts in global trade growth

Notes: The figure plots 95% confidence intervals surrounding estimates of the income elasticity of imports recovered by applying a standard (simple) cross-country gravity equation to a balanced panel of nearly 400,000 different exporter-importer-good triples.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development; World Bank.

While we can’t rule out the possibility that the relationship between income and trade has changed over time, we think the evidence is also consistent with a simpler explanation. The causal effect of income growth on trade growth may have stayed roughly stable over time, while other forces—including shifts in the demand for tradeables, changes in trade costs and the availability of trade finance, and the ebbs and flows of protectionist trade policies—have played the starring role in driving global trade over the past two decades, and will continue to do so in the future.

Peak trade view #2: A ‘structural’ trade slowdown

The collapse in global trade growth in 2011 is an example of the influence of other such factors. The slowdown in trade flows across the globe during the US debt ceiling crisis and the euro area sovereign crisis that summer was far more severe than predicted by observable short-run (or ‘cyclical’) drivers, such as a mild slowdown in global GDP growth. This prompted many observers to conclude that ‘structural’ changes—forces operating over very long time horizons, and with the potential to drive trade growth still weaker in coming decades—were, in large part, responsible (Constantinescu et al. 2016). We think the facts sit better with an alternative interpretation: a return to trend. Setting aside the financial crisis years, global trade growth has undergone two major shifts in the past two decades:

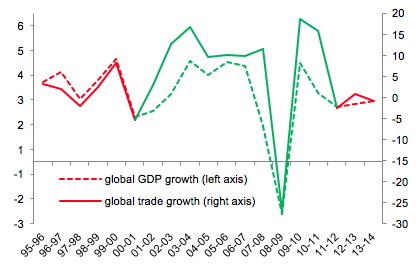

- In the early 2000s, annual growth in the value of global trade increased from tepid, but not historically slow rates (1.6% from 1995-2002) to historic double-digit levels (12.5% from 2002-2008).

- Then, in the summer of 2011, trade value growth quickly fell to levels close to zero, where it has remained for the past five years. While clearly low, these growth rates are considerably closer to historical benchmarks than the very high levels of trade growth observed during the 2000s (Figure 2).

Figure 2 The trade boom of the 2000s, not the trade stagnation of the 2010s, is historic

Notes: The figure plots annual % growth in global trade and global GDP, 1995-2014.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development; World Bank.

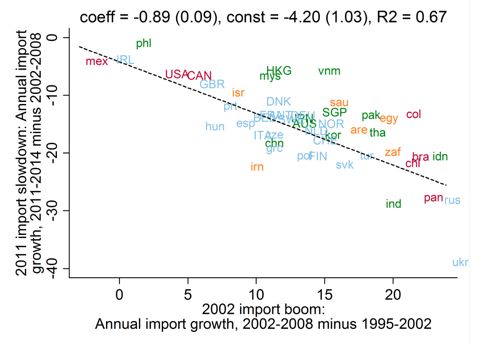

In sum, the global trade slowdown does not appear to be the beginning, or the middle, of a downward deviation from a 70-year trend of globalisation, but instead marks the end of a decade-long upward deviation from this long-run trend—the trade boom of the 2000s. This is evident not just at the aggregate level, but also when we dig deeper into individual trade flows. For example, Figure 3 shows that the countries that dramatically increased their import growth in the 2000s (such as India and Russia) saw the largest import growth declines in 2011, while countries that experienced a mild acceleration in the 2000s (such as Mexico and the Philippines) saw their import growth rates only mildly affected by the global trade slowdown.

Figure 3 The trade slowdown is, in large part, the end of the 2000s trade boom

Notes: The figure plots the ISO codes of 49 countries that, together, account for roughly 95% of global imports. Imports are measured in value terms. The regression results reported in the figure are weighted by each country’s average share of global imports, 2002-2014. The four colours of the plotted countries represent four geographical regions: Africa and the Middle East (orange), the Americas (red), Asia (green) and Europe (blue). Countries plotted in lower (upper) case featured 2002 per-capita GDP of less than (greater than) current USD $20,000.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development; World Bank.

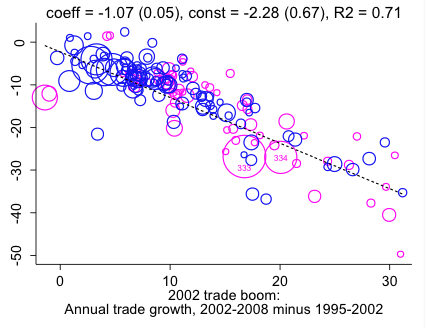

As Figure 4 makes clear, a similar pattern is also visible at the level of individual goods: those goods that saw the largest increases in the rates by which they were traded in the early 2000s then saw these growth rates fall back to baseline during the global trade slowdown.

Figure 4 Trade in specific goods accelerated in the 2000s, then returned to baseline during the global trade slowdown

Notes: The figure plots 166 goods that account for 95% of global trade between 2002 and 2014. Dotted line represents regression of vertical on horizontal axis. Each bubble represents one of 255 three-digit UNCTAD good codes. Bubble size represents the good’s average share of global trade, 2002-2014. The regression results in the figure are weighted by these shares. The displayed categories 333 and 334 each represent petroleum. Manufactures are plotted in dark blue; commodities are plotted in magenta.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Peak trade view #3: A change in the EM growth model

Finally, many observers suggest that, by beginning to turn away from export-led growth models, EMs—and, especially, China—have driven the trade slowdown and may weigh on trade growth further in coming decades.1 We agree that long-run declines in Chinese trade growth likely reflect important and potentially persistent changes to the Chinese economy, and that these changes may impose an important drag on the open economies of Asia in future (for example, China alone accounted for a third of the slowdown of South Korea’s exports during the global trade slowdown).

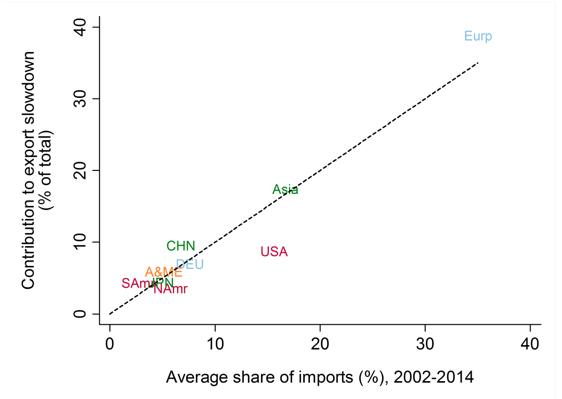

However, because China and other EMs don’t (yet) account for a large enough share of global trade, their slowing import growth matters less for the global picture than import growth declines in developed markets, particularly in Europe. Europe imports roughly 43% of global traded goods, but accounts for only roughly 20% of global GDP. It represents an important source of external demand for nearly all of the world’s major exporters, and decreased its rate of import growth by slightly more than the global average in 2011. Weighing each country’s import slowdown by its share of global trade (a ‘shift-share’ framework), we find that Europe accounts for roughly half of the global trade slowdown. By contrast, China—which imports a far smaller fraction of global trade, but slowed its rate of import growth at a comparable pace—contributed only 10% (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Europe imports a large share of global trade, and was the key driver of the global trade slowdown

Notes: The figure decomposes the global trade slowdown of 2011 into seven comprehensive categories of importers: Europe, ex-Germany (Eurp), Asia, ex-China and Japan (Asia), the USA (USA), Germany (DEU), China (CHN), North America (NAmr), Japan (JPN), Africa and the Middle East (A&ME), and South America (SAmr).

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research; United Nations Conference on Trade and Development; World Bank.

Downside risks are prominent, but ‘peak trade’ is premature

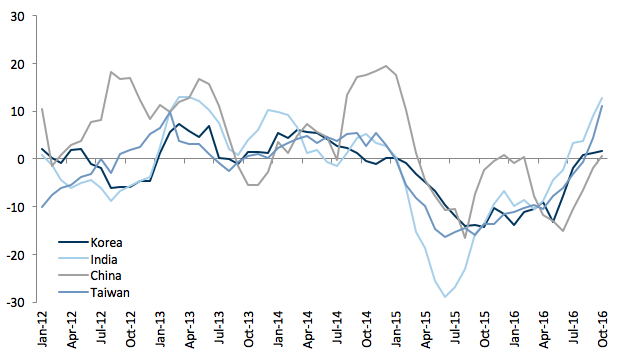

With the UK voting to leave the EU, US President-elect Trump highlighting his intention to withdraw the US from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and the potential for political populism to make inroads in continental Europe, the outlook for global trade is uncertain, and the downside risks from policy have risen. While it is easy to get pessimistic about the prospects for trade growth based on recent political news, it is however worth noting that we have seen some progress towards important trade agreements (such as the current negotiations between Japan and the EU), and that some trade flows—including flows sent from key global exporters in Asia (Figure 6)—have quickened in 2016.

Figure 6 Some recent signs of global trade growth—including exports from key Asian countries—have been encouraging

Notes: The figure plots the 6 month moving average of annualised 6 month % export growth (seasonally-adjusted) for the displayed exporter.

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research; Haver Analytics.

To sum up, we do not think that the stagnant trade growth of the past five years is more sinister than the typical ebbs and flows associated with shifts in income growth, technological innovations, and policy changes that have driven the growth of global trade since World War II. Though material downside risks to the trade outlook are highly visible at the moment, a conclusion that this represents ‘peak trade’ is, in our view, premature.

See the the original for references.

When I read Goldman Sachs staffers wagging their fingers at such things as protectionist “sentiment” and political “populism” I get the same kind of ringing in my ears as I get when all sorts of other “experts” berate the general population for not knowing what’s good for them and making “illogical” choices. But hey, wait a minute, aren’t we all supposed to be rational actors, guided by the invisible hand towards maximizing our utility?

So what gives? Adam Smith certainly never mentioned anything about people needing Goldman’s advice else the whole thing falls apart.

On the other hand, maybe it’s all just a load of hokum and Tickerbell is only real just so long as we all believe.

It isn’t just the finger wagging at potectionist sentiment and political populism that gets me, it is the blaming “shifts in income growth” calling it an ebb and flow with no recognition whatsoever that there has been no growth for a large percentage of the population. And that number is growing.

It always amazes me that supposedly smart people can miss that people with inadequate income are no longer customers for X, in this case trade goods, because they have no money. And the more people you put in this position the further the market shrinks. Then the onky thing that grows is protectionist sentiment.

But I, and people like me, are irrational.

These smart people don’t miss it. They provide intellectual cover and succor for those gobbling up all the gains in our economy. What else could they have done!?

I’d guess Goldman Sachs employs two sets of economists – one set writes PR pieces (like the above) for marketing reasons, to get investors and politicians to support their agenda.

The other set does internal analysis on Goldman Sachs business deals and never talks to or interacts with the first group. This would include their oil trading group, their subprime mortgage trading group, their bundled student loan trading group, etc.

Absolutely. And the question: Does this make me look fat? does not exist.

And no one buys jewellery, because it has no utility.

Considering the long history of jewelry, going back tot he paleolithic, it must have some utility.

In theory, nobody would advertise too, because, according to these ridiculous models, humans are “rational, utility maximizing” actors.

As far as jewelry, I’d argue that’s another way to disprove. People buy it and pay stupendous sums for the looks of some uncommon and pretty rocks. It’s heavily due to the marketing campaign of companies like De Beers.

See here:

http://www.bansheemann7.com/7439/diamonds-are-for-suckers-why-im-never-buying-diamonds

Worse it is fueling conflict abroad. It’s a sad reflection of our culture.

Labeling opposition to TTP/TTIP as protectionist is rich, when those treaties are mostly about protectionism for rents collected by selected intellectual-property-based industries.

Demand is mentioned twice, and linked to trade volumes in the second reference. Very weakly I’d assert.

Austerity’s impact on income and demand is not mentioned. Income inequality is not mentioned.

If us proles have less disposable income (caused by austerity and increasing income inequality), One would expect your “trade beta” to fall.

Dear Sirs , who drives “consumer spending” and thus growth?

Hint: It’s Consumers, the vast mass of consumers.

But you see, if I give a hundred gazillion dollars to your boss, he might lend some of that to you and the other plebs, thereby driving demand. Isn’t it wonderful!

but, I, and the other proles kniw we have to pay it back ×2. The boss is only reducing our wages,

Neo-liberalism is a system that uses debt to keep going and the world has nearly maxed out. It’s underlying neoclassical economics uses spurious assumptions about money and debt and so no one sees the problems coming.

2008 – “How did that happen?”

Twelve people were officially recognised by Bezemer in 2009 as having seen 2008 coming, announcing it publicly beforehand and having good reasoning behind their predictions. They all thought the problem came from excessive debt levels.

Having all our mainstream experts using spurious assumptions about money and debt, doesn’t actually stop the whole thing blowing up.

Attributing 2008 to a “black swan” has allowed us to think more debt can be used to solve a debt crisis, needless to say the debt levels are much higher than 2008 and excessive debt has now spread through emerging markets. China and emerging markets are not going to provide an engine of growth next time.

The other day I was watching a particularly apocalyptic video from Peter Schiff, he is no fool, he was one of the twelve that saw 2008 coming. Steve Keen is another one of the twelve and he is of the same opinion.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qrz76_j9MRs

(Ignore first 50 secs. just intro).

Most people don’t realise money = debt, all the money in existence has a corresponding amount of debt.

We can see what Steve Keen saw by looking at the US money supply.

http://www.whichwayhome.com/skin/frontend/default/wwgcomcatalogarticles/images/articles/whichwayhomes/US-money-supply.jpg

No, it wasn’t a black swan and if the FED could have understood what the money supply was telling them they could have nipped it in the bud.

M3 was going exponential and a credit bubble was forming, Steve Keen saw it in 2005.

The spurious assumptions on money and debt in neoclassical economics leave you blind.

How did things used to work?

We re-cycled the surplus.

At a personal level through strong progressive taxation to provide low cost housing, education, healthcare and other services.

Neo-liberalism uses Payday loans, student loans, subprime mortgages, subprime auto loans, etc … When the consumer maxes out on debt it stops working.

Trade dies when debt maxes out, nearly there.

At a national level ….

When Keynes was involved in putting together the new international order after the Second World War, mechanisms to recycle the surplus were put in place in the Bretton-Woods agreement.

When the Euro was designed we assumed the Euro area would naturally reach a stable equilibrium and there are no mechanisms to recycle the surplus.

The Euro-zone is polarising and the poorest nation, Greece, has collapsed under its debts and the other Club-Med nations are heading that way.

The sticking plaster solution of debt maxes out, recycling the surplus can keep the whole thing going forever.

Wealth concentration with neo-liberalism.

2014 – “85 richest people as wealthy as poorest half of the world”

2016– “Richest 62 people as wealthy as half of world’s population”

Doing the maths and assuming a straight line …….

5.4 years until one person is as wealthy as poorest half of the world.

It’s going to fall over and die through lack of demand.

Larry Summers one time 100% neo-liberal:

“But that was yesterday’s problem, Summers said. The economy now faces secular stagnation, or a chronic lack of demand.”

This is why you re-cycle the surplus.

Neoclassical economics saturated the US economy in debt in the 1920s. They used debt to maintain demand.

Wall Street played its games with securitisation to inflate the US stock market using debt.

Keynes looked at 1920s neoclassical economics and the Great Depression to learn some lessons.

1) Only fiscal policy would work in a severe recession; we are just coming back to this way of thinking eight years after 2008.

2) The system was demand driven which is why fiscal policy works, it creates jobs and wages which are spent into the economy and trickle up.

3) He thought the system trickled up, we assumed it trickled down, cut taxes on the wealthy and inequality soared.

4) Income is just as important as profit; it is income that looks after the demand side of the equation.

5) Re-cycling the surplus works in the long run unlike debt.

We went back to 1920s neoclassical economics and lost all Keynes 1930s updates.

Neoclassical economics saturated the economy in debt. We used debt to maintain demand.

Wall Street played its games with securitisation to inflate the US housing market using debt.

It’s exactly the same.

1920s/2000s – high inequality, high banker pay, low regulation, low taxes for the wealthy, robber barons (CEOs), reckless bankers, globalisation phase

1929/2008 – Wall Street crash

1930s/2010s – Global recession, currency wars, rising nationalism and extremism

The US moved to the New Deal in the 1930s, Europe didn’t and let the populists rise.

The US hasn’t remembered and has now got Trump.

The credit boom of the Roaring Twenties was entirely due to one bull-headed man: Henry Ford.

He was so angry with bankers that he founded what today one might describe as a manufacturer’s bank: Ford Motor Credit. (1920)

He had to establish FMC as a stand alone corporation — with CLEAN books — because his own books were a total mess, impossible to audit. Yup. (!!!)

[ Ford’s books were only straightened out after his death. ]

FMC under-cut small town bankers, and Big Bankers, too. It provided “flooring” — wholesale credit to his dealers — and retail credit — to purchasers of Ford cars.

FMC raised its money, mostly, in the beginning, from Boston’s insurance industry. They couldn’t get enough of its debt. It paid more than US Treasuries. It was AA to AAA.

General Motors took prompt notice. Quickly, GMAC was founded to mimic FMC.

Such ‘manufacturer’s banks’ exploded onto the scene for every manner of ‘white goods.’ ( household appliances )

It was THIS sequence that made the Twenties roar. No economist was consulted.

It was all inspired by Ford’s personal hatred of bankers. So, de facto, he became one of the nations largest bankers. Ironic, no?

&&&

Debt did not blow up the American economy circa 1930. ( The hyper contraction known as the Great Depression dates from December of that year — not 1929. )

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act blew up German-American trade. Britain still ran her own trading bloc — the Commonwealth. France had her trading bloc, too. The German market was the excluded party for both. ( ie tariffed out )

Germany was selling to the US in grand style, as America had no tariff wall against Germany’s manufactured goods. Further, the US dollar was literally as good as gold. Germany was importing American bullion in grand style — to pay off her war debts to France and Britain.

{ America wanted France and Britain to pay off their debts — but largely got stiffed. America did not want reparations from Germany. Wilson did everything in his power to talk Britain and France out of the crazy idea. }

The new tariff regime blew-up German-American trade, sending both nations into the gutter. The primary market for surplus American foodstuffs was GERMANY.

In a flash, every manner of German trade debt went sour, debts often enough held in US institutions.

Tariffs designed to protect (Republican) farmers — blew up their bankers — and their primary overseas customer.

&&&&

The recent period was a financial fad — a bubble.

The implosion of same was obvious to me — predicted July 2003.

But then, I predicted the multi-decade bull market, August 11, 1982 the Wednesday before it exploded upwards. Yes, the Mexican crisis triggered the super bull market. Volker HAD to flip — to drop interest rates. Even Henry Kaufman saw the same dynamic, August 17, 1982 — the famous Tuesday.

We are all in for a rough ride because the dominant economy at this time is Red China’s — and it’s a Command Economy.

That’s a big simplification. The 1920s was the era of consumer credit of all sorts, partly due to electrification and partly due to new consumer durables, like washing machines, both wringer washers and new electrical washers.

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3396

The first explanation I’ve ever seen of the Great Depression that misses the stock market implosion.

Unique and hardly plausible.

From the banker’s book of excuses perhaps?

It wasn’t us.

It never is.

It astonishes modern Americans, but the nation west of the Hudson was not that involved with Wall Street.

Further, like the Dot Com bubble, which also crashed, the NYSE debacle did not ripple out to cripple the debt driven economy.

One is even reminded of the Rich Man’s Panic of 1906-07. It got that title by way of being just so.

The Federal Reserve System is a clone of First National City Bank — J.P. Morgan’s ‘banker’s bank.’ It was this institution that he used to stop bank runs. In one famous instance, JP sent a private train — express — overnight — to upstate New York — loaded with gold and Pinkerton men. This stopped the bank run rather immediately.

You can really track the Great Depression by following commodities prices. Once the tariffs kicked in, the German-American trading engine ground to a rapid halt. Suddenly, they couldn’t finance food imports.

Urban Germans began to starve, the American farmers to weep.

[ This episode was a huge trigger for Adolf’s fantasy about conquering Ukraine, too. ]

The crisis rapidly devolved… with results universally known.

The average businessman does not hang on Wall Street’s every whim. Instead he takes his cue from his creditors.

The first blow was Bank of the United States:

“On December 10, 1930, a large crowd gathered at the Southern Boulevard branch in the Bronx seeking to withdraw their money, and started what is usually considered the bank run that started the Great Depression (though there had already been a wave of bank runs in the southeastern part of the U.S., at least as early as November 1930). The New York Times reported that the run was based on a false rumor spread by a small local merchant, a holder of stock in the bank, who claimed that the bank had refused to sell his stock.[14]

{ Wiki has this screwed up. He wanted the bank to redeem his BoUS stock for cash, ie buy his stock back. The bank had been selling shares to depositors on top of taking deposits. }

“By the midday, a crowd of 20,000 to 25,000 people had gathered and had to be controlled by the police, and by the end of the day 2,500 to 3,000 depositors had withdrawn $2,000,000 from the branch. However, most of the 7,000 depositors who came to withdraw their money left their assets in the bank. One person stood in line for two hours to claim his $2 account balance. As the news spread, there were smaller runs at several other branches in the Bronx as well as in the East New York section of Brooklyn.[14]” Wiki

The international banking crisis started in Austria — and then went global.

“Creditanstalt had to declare bankruptcy on 11 May 1931. This was one of the first major bank failures that initiated the Great Depression.[2]:2–3 [3][4] Chancellor Otto Ender rescued Creditanstalt by distributing the enormous share of costs between the Republic, the National Bank of Austria and the Rothschild family. Nationalization plans advanced by the Social Democrats were rejected. However, the institute was de facto state-owned after Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß in 1934 ordered the merger of the institute with the Wiener Bankverein, thus changing its name to Creditanstalt-Bankverein. The Creditanstalt bankruptcy and its impact in producing a major global banking crisis provided a major propaganda opportunity for Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party: it allowed them to further blame Jews for German and international economic and social troubles ”

Wiki

That these epicenters were Germanic and American buttresses my point. They both had significant exposure to international trading accounts.

As for “us” — it was the US Congress that erected the tariffs.

“From the banker’s book of excuses perhaps?

It wasn’t us.

It never is.”

Non sequitur, then.

As for being a ‘unique’ take on the tragedy… orthodoxy is closer to the mark.

Richard Koo frames it all in terms of debt, debt deflation and what happens to the money supply when the majority are paying off debt, with easy to understand diagrams normally only Central Bankers have access to, the total debt picture in the US.

The New Deal involves Government borrowing that boosts the money supply (money = debt) and begins the recovery. It’s all about debt and money.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

(First 12 mins.)

Ben Bernanke read Richard Koo’s book and stopped the US doing austerity. Ben Bernanke learns from Richard Koo, he’s pretty good.

America wanted France and Britain to pay off their debts — but largely got stiffed. America did not want reparations from Germany. Wilson did everything in his power to talk Britain and France out of the crazy idea.

America didn’t seem to take into account the only way France and Britain could pay off their debts was getting the money from Germany through reparations.

So says Michael Hudson in “Super Imperialism”.

Michael Hudson and Richard Koo are reliable sources in my book.

But the Germans DID ship gold to France and Britain… gold acquired from America.

The French and the British STILL stiffed the USA.

In the 1960s, when France had largely recovered, Paris was STILL not willing to pay ANY of her old war debts to America.

And the USA stiffed American investors in its OWN gold backed war debt. This shafting was approved by the USSC, too. They had to take fiat US dollars, instead.

Blert…germany never paid anyone back…sorry you have drunk the flavor-aid…total german payments made to creditors and war reparations for ww1 stood at a grand total of 8% of total outstandings at the beginning of ww2…greece was to obtain a small piece and with the creation of the bank of international settlements, the institution was trustee and among other things, the debts were to be secured by the german rail system…the bis claims it burned the agreement in 1948 without any authorization and thus the debt is now magically void…

The fable presented by the german plutocracy was just an attempt to push back against the spartacus movement(perhaps fearing rosa luxemburg might rise up again from landwehr canal) and the population having become tired of the nobility eating all the economic vittles…so the average german was lied to by its “betters” & the average german (& obviously non germans) have eaten up this fairy tale…

Germans are great at convincing the world they are not a criminal enterprise…

The loud claims that germany “paid” ww2 reparations is another joke…they didnt even pay half of what they owed america…and the american agreement to cut in half was predicated on germany paying other countrues (ie greece) back…it is specifically written in the agreement…but no one reads those things…

Perhaps a quitam case or writ of mandamus might shift the germans back to reality…

Germany is now and has always been a giant ponzi scheme…DB being the prime example…but germany has taken care of moodys and s&p so reality doesn’t matter…all that counts is the little stamp of approval of “investment grade”…

But as to the issue of trade…the top 25 thousand global enterprises use trade to shift profits around and claim deductions and losses…by being global they can keep a large percentage of their revenues hidden from domestic tax officials…

The head of the bank of the united states that you mention was that fine upstanding citizen who happened to be the uncle of roy cohn…that roy cohn…and as for the knickerbocker trust crash you alude to for 1906-07…mayhaps a look at the copper money that came to new york to show the moneymen how the games is played might actually help explain the events of 07…

The only thing that counts is continued access to capital and credit and the ability to promote the notion that diamonds, gold and electronic digits on a bloomberg screen have some value…

BIS was founded May 17, 1930 — precisely because Germany STOPPED paying reparations… which by the terms of the agreement had to be paid in gold — or its equivalent. ( US dollars sufficed since they were good as gold, literally. )

Germany’s financial crisis harmed the US more than any other power — because we’d become its biggest creditor. ( If you exclude WWI reparations.)

The Weimar hyper-inflation had NOTHING to do with gold reparations. Fiat money simply would not do. That crazy era was driven by German spending on social programs — primarily its over-built railroad. The Weimar madness was only stopped when the British came in and mandated huge, huge, cut-backs in said spending; and when its (mad printing) architect died.

It is also of record that Adolf flatly stopped further gold reparations payments… and made the Reichsmark a purely fiat currency.

Even a stopped clock is right twice a day.

The tariff wars had made it virtually impossible for Germany — or the USSR — to obtain export income.

Stalin’s solution was the Holomodor. A staggering fraction of the stolen grain was exported!

All of this history ought to scare one stiff WRT a tariff war with Red China.

your projection cannot be straight line, it has to be a poisson distribution. In addition there are distribtuve effects – aka children and ex wives.

The sticking plaster solution of debt maxes out, recycling the surplus can keep the whole thing going forever.

Recycling the surplus by taxing the rich might work temporarily if it could ever be enacted (it can’t and won’t be for obvious reasons) in a purely economic sense, but that ignores the fact that debt based consumption is just a fancy term for consuming tomorrow’s resources today and then financially paying for it when or if we ever get around to it. Unfortunately, while dollars might indeed be infinite, the natural resources they’re paying for certainly aren’t. This pyramid scheme (which is what it is) is also reliant on the US dollar being the world’s reserve currency, which it won’t be forever either. The best laid plans of mice, economists, and politicians…

You hit the nail on the head and i agree with you.

Peak trade? Not while there is stuff to extract and people to enserf and money to be looted,..

The limit to growth of metastatic cancer is the cachexia and death of the sufferer…

It is early here in the Mountain Time Zone, and my brain is still trying to adjust to the lack of oxygen at 5500 feet, after bathing for 3 weeks in rich sea-level air, but …. reading the above conjured up images of suited guys poking about in the steaming entrails of x-and-y axes while mumbling garbled and opaque fragments of prophecy.

Time out for a Wafo Moment, then

————

Time to set goals. Goal # 1 is to make products cross borders.

Thankfully, I guess, there is no limit to trade. Ship a Iowa corn cob to China, ship a Chinese tractor to Iowa. Ship a baseball card to Japan, get a different baseball from Japan. If you run out of money to buy American baseball cards, ship a used Chinese tractor to Japan. If you run out of used stuff, ship a Chinese millionaire to America. The game can’t possibly end!

Craazyboy, I am worried. You and your doppelgänger, crazyman, have begun to make sense in the last month. Do you think it is me? Have I gone off the deep edge?

It started a few months ago, when I began to confuse headlines at The Onion with headlines at NYT and WaPo. And, vice versa. I began to doubt my ability to separate reality from fantasy. And, now …. crazy has become sane. Help me!

Sorry, Eclair. We’re all going to have to accept that the writings of Lewis Carroll and Franz Kafka, contrary to conventional wisdom, are actually non-fiction.

That’s because Haim Saban and friends now own all three publications. They write the headline once and use it 3 times. Economy of scale – you need fewer reporters and editors. Makes your headlines more competitive for export internationally too! You just need to learn this business stuff.

The other key thing to know to be truly crazy is you must realize there is no reality, at least beyond the Five Elements and Laws of Thermodynamics. Newton’s stuff too. Quantum anything isn’t real. Come to think of it, biology is real. Shouldn’t forget that. But some realities have higher probabilities of existing than others. Lots of people are crazy, probably most. It’s just that it’s exceedingly difficult to root out high probability realities and most crazy people get it wrong and just believe low probability crazy stuff. But you can get better at it if you try really, really hard.

Honestly it wouldn’t even surprise me at this point if all three of those publications start publishing articles about the Power Rangers saving us from terrorists in order to promote Sabans pet franchise’s new movie. Feels like NYT and WaPo articles are just getting that fictional, the propaganda is being laid so deep.

Yes. Todays economists are yesterdays astrologers. Dependent on court patronage for their very existence.

How very self-serving of Goldman Sachs.

They are looking for more ways to extract economic rent from the rest of society and to make themselves richer. That’s what this is about. The functions that actually add value to society now consists of a very small amount of their business if you think about it.

Finance has become about people moving numbers around a spreadsheet and then betting them all. That’s more or less what the levels and levels of traders these days do. It’s of negative social value to society, but it makes the banks very rich. What it is really is a transfer of wealth from the productive sectors of the economy to the looters.

That is what Goldman Sachs seems to be doing these days in writing these types of articles. They need to keep up appearances so that it leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy. The fact that the looting of the economy has destroyed the lives of many people around the world does not faze them at all, not does the public backlash. I’m sure they’ll make money off outsourcing and where they can get fees.

Let’s just put it this way, if there is ever a revolt and they lose all of their stolen wealth, I’m not shedding any tears.

A good article on Goldman Sach commodity deals that proves your point is here:

http://foreignpolicy.com/2011/04/27/how-goldman-sachs-created-the-food-crisis/

reminds me of the French nobles who monopolized and gladly caused a bottleneck shortage of wheat and made a killing just as France was starving; and they thought they were so smart… until the revolution. Not that we’re gonna get blood in the streets – but the confusion is rising. All the talk on tv this morning is about how we need to keep our cool and maintain the “Western” model… they are panicky. Makes me think this is pure Goldman dysinfo because peak trade has indeed happened. I wonder what Goldman will do with all those warehouses full of commodities? The Earth has been too generous with us. We were so foolish to think we could match her generosity with endless massive human consumption. Where are our brains??

Too many of us, the brain kind of stops with the limbic system and the stuff that feeds into it.