We’ve said for the last couple of years that private equity has not been earning enough to compensate for its extra risks, that of high leverage and lack of liquidity.

One of the core tenets of finance is that extra risk-taking should be rewarded with higher returns over time. But for more than the last decade, typical investor portfolios of private equity funds haven’t delivered the additional returns, typically guesstimated at 300 basis points over a public equity benchmark like the S&P 500.

We’ve pointed out that even that widespread benchmark is too flattering. Private equity firms invest in companies that are much smaller than the members of the S&P 500, which means they are capable of growing at a faster rate over extended periods of time. The 300 basis point (3%) premium is a convention with no solid analytical foundation. Some former chief investment officers, like Andrew Silton, have argued that a much higher premium, more like 500 to 800 basis points (5% to 8%) is more appropriate. And that’s before you get to other widespread problems with measuring private equity returns, such as the fact that they are routinely exaggerated at certain times, namely right before a new fund is being raised by the same general partner, late in a fund’s life, and during bear markets, all of which goose overall results.

And that’s before you get to the fact that some investors use even more flattering benchmarks. As Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou pointed out by e-mail, in the last two years, more and more investors have switched from using the already-generous S&P 500 to the MSCI World Index as their benchmark. Why? Per Phalippou: “Because the S&P 500 has been doing very well over the last three years, unlike the MSCI World Index.”

So why hasn’t private equity been producing enough over the past decade to justify the hefty fees? The short answer is too much money chasing deals. Private equity’s share of global equity more than doubled from 2005 to 2014.

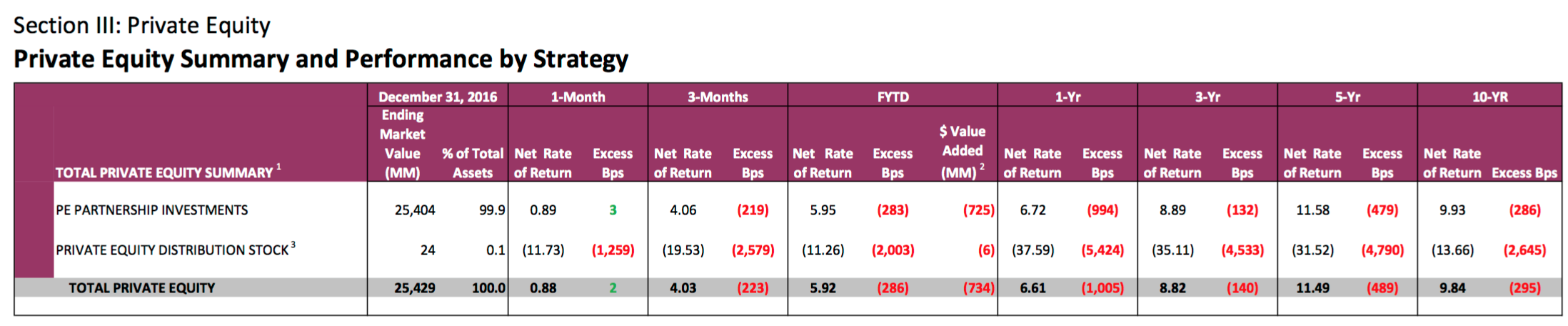

And you can see how this looks in CalPERS’ latest private equity performance update, from its Investment Committee meeting last week (from page 14 of this report). In fairness, CalPERS does have a more strict private equity benchmark than many of its peers:

Since that chart is still mighty hard to read (by design?), let’s go through the sea of read ink.

The only period in which CalPERS beat its benchmark was for the month before the measurement date of December 31, 2016, and that by a whopping 3 basis points. In all other measurement periods, the shortfall was hundreds of basis points:

3 months (219)

Fiscal YTD (283)

1 year (994)

3 years (132)

5 years (479)

10 years (286)

To its credit, CalPERS has been cutting its private equity allocation. CalPERS had a private equity target of 14% in 2012 and 2013; it announced last December it was reducing it from 10% to 8%. Like so many of its peers, CalPERS hoped that private equity would rescue it from its underfunding, which came about both due to the decision to cut funding during the dot com era, when CalPERS was overfunded, and to the damage it incurred during the crisis. At least CalPERS is finally smelling the coffee.

However, even with these appalling results, CalPERS does have another avenue: it could pursue private equity on its own, which would virtually eliminate the estimated 700 basis points (7%) it is paying to private equity fund managers. CalPERS confirmed this estimate by Ludovic Phalippou in its November 2015 private equity workshop. Since at that point it had gathered private equity carry fee data, that means the full fees and costs are at least that high; it would presumably have reported a lower number or flagged the figure as an high plug figure. Getting rid of the fee drag would mean much more return to CalPERS and its retirees, and would make private equity more viable.

CalPERS has two ways it could go. One would be a public markets replication strategy, which would target the sort of companies private equity firms buy. Academics have modeled various implementations of this idea, and they show solid 12-14% returns. However, as we’ve discussed at length, and some pubic pension funds have even admitted, one of the big attractions of private equity is…drumroll…the very way the mangers lie about valuations, particularly in bad equity markets! Private equity managers shamelessly pretend that the value of their companies falls less when stocks are in bear territory, giving the illusion that private equity usefully counters portfolio volatility. Anyone with an operating brain cell knows that absent exceptional cases, levered equities will fall more that less heavily geared ones. So the reporting fallacy of knowing where you really stand makes this idea unappetizing to investors.

The other way to go about it would be to have an in-house team that does private equity investing. A group of Canadian public pension funds has gone this route and not surprisingly, reports markedly better results net of fees than industry norms. And this is becoming more mainstream, as Reuters reported last Friday (hat tip DO):

Some of the world’s biggest sovereign wealth funds are increasingly striking their own private equity deals rather than relying on external fund managers, in a drive to cut costs and gain more control.

With some $6.5 trillion in assets, sovereign investors already account for 19 percent of capital committed to private equity, according to data from research firm Preqin.

But mega-funds such as the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF) and Singapore’s GIC, are hiring specialists to find or vet deals – enabling them to negotiate with private equity firms from a position of strength or to go it alone.

In 2012 sovereign investors participated in just 77 direct private equity deals. By 2016, that had risen to 137, Thomson Reuters data shows. Deal value more than trebled to $45.2 billion from $14.8 billion….

This allows funds to better protect their interests when markets go south. One sovereign investor who spoke on condition of anonymity said that during the global financial crisis, some external funds behaved irrationally.

“They had different liability streams than us, so they were under pressure to sell at a time when they should have been investing more,” the source said. “Going more direct means you don’t have to worry about whether your interests are aligned with other investors’.”

And to its credit CalPERS is considering joining this trend…after having been deterred from leading it. From a 2016 post:

In 1999, CalPERS engaged McKinsey to advise them as to whether they should bring some of their private equity activities in house. My understanding was that some board members thought this issue was worth considering; staff was not so keen (perhaps because they doubted they had the skills to do this work themselves and were put off by the idea of being upstaged by outside, better paid recruits).

In hearing this tale told many years later, I was perplexed and a bit disturbed to learn that the former managing partner of McKinsey, Ron Daniel, presented the recommendations to CalPERS of not to go this route. Only a very few directors (as in the tenured class of partner) continue at McKinsey beyond normal retirement age; one was the head of the important American Express relationship at the insistence of Amex. Daniel served as an ambassador for the firm as well as working on his former clients. Why was he dispatched to work on a one-off assignment that was clearly not important to McKinsey from a relationship standpoint, particularly in light of a large conflict of interest: that he was also the head of the Harvard Corporation, which was also a serious investor in private equity?

Although the lack of staff enthusiasm was probably a deal killer in and of itself, the McKinsey “no go” recommendation hinged on two arguments: the state regulatory obstacles (which in fact was not insurmountable; CalPERS could almost certainly get a waiver if it sought one), and the culture gap of putting a private equity unit in a public pension fund. Even though the lack of precedents at the time no doubt made this seem like a serious concern, in fact, McKinsey clients like Citibank and JP Morgan by then had figured out how to have units with very divergent business cultures (investment banking versus commercial banking) live successfully under the same roof. And even at CalPERS now, there is a large gap between the pay levels, autonomy, and status of the investment professionals versus the rank and file that handles mundane but nevertheless important tasks like keeping on top of payments from the many government entities that are part of the CalPERS system, maintaining records for and making payments to CalPERS beneficiaries, and running the back office for the investment activities that CalPERS runs internally.

Why do I wonder whether McKinsey had additional motives for sending someone as prominent as Daniel to argue forcefully (as he apparently did) that CalPERS reject the idea of doing private equity in house? Clearly, if CalPERS went down that path, then as now, the objective would be to reduce the cost of investing in private equity. And it would take funds out of the hand of private equity general partners.

The problem with that is that McKinsey had a large and apparently not disclosed conflict: private equity funds were becoming large sources of fees to the firm. By 2002, private equity firms represented more than half of total McKinsey revenues. CalPERS going into private equity would reduce the general partners’ fees, and over time, McKinsey’s.

In keeping, as we pointed out in 2014, McKinsey acknowledged that the prospects for private equity continuing to deliver outsized returns were dimming. That would seem to make for a strong argument to get private equity firms to lower their fees, and the best leverage would be to bring at least some private equity investing in house, both to reduce costs directly and to provide for more leverage in fee discussions. Yet McKinsey hand-waved unconvincinglyabout ways that limited partners could contend with the more difficult investment environment, and was discouraging about going direct despite the fact that the Canadian pension funds had done so successfully.

Better late than never. Let’s hope CalPERS pursues this long-overdue idea.

With regards to the idea of doing private equity in house, can a pension fund act as a bank or credit union to it’s pension members and others?

Seems to me this would create an effective bond between the pension/bank and it’s community, providing capital to it’s users and the region.

Is this possible? Not a finance person.

IMO, a fairly good strategy in this would be for the pension fund to also offer life-insurance, as life-insurance works quite well with pensions (if you pay pension, you don’t have to pay life insurance and vice versa. at the same time, life-insuance premia may help to pay the pensions).

re PE benchmarks:

“ As Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou pointed out by e-mail, in the last two years, more and more investors have switched from using the already-generous S&P 500 to the MSCI World Index as their benchmark. “

Changing longstanding benchmark standards for better optics is a large red flag, imo.

CalPERS seems to be trending in a better direction. Reducing the PE portion of investments by almost half – from 14% to 8% – is significant. The past few years of detailed reporting by you, Morgenson at the NYT, Appelbaum and Batt, Bloomberg and others have no doubt influenced this trend. (Although I’m sure CalPERS would deny any connection.)

Bringing PE investing in-house would probably require expertise CalPERS doesn’t currently have but could acquire. It seems like a good idea.

Thanks so much for your continued reporting on PE, CalPERS and pensions.

700 basis points or more creamed off the top?… Wowsers!! Would love to see CalPERS disintermediate Private Equity firms. Couldn’t happen to a nicer bunch. Who knows, maybe CalPERS can form a cooperative in-house tax exempt PE joint venture with some other states’ investment funds, which might also enable them to take advantage of lower tax exempt rates on the funding side? Seems to me there could also be some magic in participation with Sovereign Wealth Funds as a small percentage of the overall portfolio mix. Would want to see CalPERS implement independent risk management oversight and have strong internal controls to prevent political insiders from taking advantage of an in-house operation, though.

With all the money they have they could disintermediate the entire economy.

They could buy a big slice of some state or even a country, build their own territory with residences, doctors, healthcare, utilities, facilities, locally grown food, restaurants, outdoor recreation and let pensioners go there and stay for free.

It could be staffed like one of those fancy African safaris.

That would probably be cheaper than sub-contracting it to “the economy”.

That might be the trend in the future anyway.. It’s like a version of all the grroups that left England in the Pilgrim Days. They couldn’t take it anymore — it’s weird how there were so much less people there in those days and people stiill had to leave due to conflicts. That should tell economists it’s not about “resources”. It’s seomthing else. If Merry Olde Englande isn’t a a bulls-eye then manbe something out of Bocaccio’s DECAMERON, where people take refuge from the plague and entertain each other. Or, for those whose reference points are more contemporary, Cormac McCarthy’s THE ROAD. You need a little place to escape from soemthing like that and the “economy” probably won’t be very hospitable at the rate it’s going — projecting forward that is, right now it’s still sort of viable

Yes, that means they need to consistently beat the market by 700 basis points just to match the returns from a passive indexing strategy. If you think they can do that over a 10-20+ year period, I have a bridge I’d like to sell you.

My preferred approach for them would actually be along similar lines to craazyman’s, if a bit less extreme. They manage an enormous chunk of the nation’s investable capital. Why not take advantage of that and become a market leader in governance? Rather than try to achieve above average returns by picking winners, take substantial positions in the biggest and most significant companies for the local economy, leverage that into one or more board seats, and actively participate in guiding company strategy and steering them in directions that are productive and/or create synergies with the local economy. Instead of seeking to achieve above returns by picking winners, you’d look for market returns by taking substantial positions in ‘average’ companies and making them above average. Essentially you’d be offering an index/passive investing strategy but without the governance vacuum that usually accompanies it.

That might sound a lot like what PE is supposed to do, except that PE firms very often look for short to medium term yield and often end up strip-mining companies to do it, so they end up as rent-seekers who extract a bigger slice of the pie at the cost of a net destruction of value in the long term. CALPERS is big enough to be able to take a broader and longer term view and therefore (hopefully) produce better returns over long time scales. Not only that, it would help to make the capital markets healthier and less dominated by looting and short term profit maximization.

Gotta say, wouldn’t have previously considered a connection between the setting and values expressed in The Decameron at a time of transition to something else, and a broader philosophical outlook toward developments in the economy and investments. Thank you, craazy, as the caravan moves on.

It could be like Fantasy Island with Ricardo Montalban and Herve Villechaize.

When you retire to get into a twin engine prop plane and fly to Calpersville, landing on a gravel runway bouncing up and down as the plane comes to a halt somewhere in a valley surrounded by breathtaking mountain vistas.

Then you notice somebody wearing a cream suit, dark tie and pocket square who looks like Ricardo Montalban approaching the parked plane with his arm waving in welcome. “Welcome my friends, to Calpersville, where your new life is about to begin.” Then he hands you a contract with the Calpersville code of conduct, that you must obey, or you get “disciplined”. Whoa! You didn’t bargain for that!!! What? No public drunkenness?? No smoking pot?? Everybody has to be employed in either a sport, art, craft or hobby??? What??? This was supposed to be retirement??? You just wanted to lay around. WTF???

Then you see “the guards”. They dont look very nice do they. Are those tatoos? Yes! Whoa those dudes are ripped and they look mean. Holy smokes. Its only been 5 minutes and you wanna leave. Then you hear the dogs barking. And snarling. Then. You see them! Fkkkn AA. WTF is this? They’re German Sheppards!

On the drive into town you notice nobody is on the streets — exceept for guards and dogs. That’s weird. Then you see somebody on a corner, crying, and being handcuffed. They must have had a glass of wine and gone for a walk. Drunk in public probably. Whoa!

You’d have to be careful making Calpersville. Sometimes even the best laid plans go off the rails, like the Russian Revolution. Every time they try for utopia, something bad happens. It’s amazing to me Plato wrote the Republic. Was he crazy or what? All the other dialogues aren’t bad. Some are pretty fantastic. But that one is like: WTF was he thinking???? Hahaha

Excellent as always Yves; 1 question. Just what exactly, does investing in a Pubic Pension fund require of new enrollees? *Shudder* and what do you get when you start drawing ‘benefits’? Lucky for me retirement is a ways off.

Well, I’m a very recent CalPERS retiree, and I’m flabbergasted at how badly they’re already missing their marks on these PE scams. No wonder the CEO (and who else?) had to be bribed into taking the deals. How many hidden “Heads-I-Win/Tails-You-Lose” clauses are baked into these deals over the next decade, especially as exposure draws down and the GP’s know that CalPERS ain’t buying what they’re selling in the next round. Thanks for exposing this, but I’m going to have to break-out the Tums…

Is CalPERSville Fantasy Island? More like The Village, from the 1960’s drama The Prisoner — starring Patrick McGoohan as “Number 6”. He spent each episode chewing up the scenery in the quaint Welsh folie of Portmerion, while running from a big white blob known as “Rover.” WE WANT INFORMATION. INFORMATION. “I’m not a number! I’m a free man!” Yeah. Right.

This may be a dumb question, but why not just put the money in an index fund at this point?

Beating the market by 5-8% consistently is not going to be possible. The odds of finding a Buffet like fund manager is not very good.

With all due respect I think you’re missing the most important and truly basic analysis:

10-yr total fund return 4.41% where PE – net of all the fees – was by far the star performer with 9.84%.

You have just demonstrated that you are not competent to discuss finance.

First, one of the most basic precepts of finance is the risk/return tradeoff. Anyone in a finance course or being tested for a broker’s license would be failed if they argued what you are claiming, that only absolute returns matter. We’ve debunked your misguided view at length:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/09/private-equity-underperformance-denialist-pension-consulting-alliance-tells-calstrs-to-fix-performance-problems-by-scrapping-benchmark.html

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/09/former-state-chief-investment-officer-tells-calpers-and-calstrs-to-fire-consultant-pca-over-proposed-fix-for-poor-private-equityperformance.html

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/12/our-bloomberg-op-ed-on-calpers-plan-to-get-rid-of-private-equity-risk-by-ignoring-it.html

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/09/calpers-chief-investment-officer-invokes-false-superior-returns-excuse-to-justify-fealty-to-private-equity.html

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/12/we-won-a-fight-against-calpers-over-its-plan-to-ignore-private-equity-risk.html

Second, you appear unaware of the fact that the risks of private equity manifested themselves during the financial crisis. CalPERS was hit with private equity capital calls when it didn’t have enough liquidity to meet them. It dumped stocks at the worst point in the crisis to meet those capital calls. It lost hundreds of millions of dollars, and those losses didn’t show up in private equity returns, but in its public equity returns! So the comparison you try to make is meaningless for this reason as well.

In addition, CalPERS has to manage its non-PE investments so as to be able to accommodate private equity capital calls, which come with only 5 or at mot 10 business day notice. That means keeping more assets in highly liquid, low return assets. I’ve guesstimated that that hidden cost alone (which is again reflected in the returns in the rest of the portfolio, not private equity) is worth about 100 basis points (1%) and Professor Phalippou has independently come up with the same figure.

Third, you ignore the fact that the returns provided by private equity firms are not reliable because a substantial of the asserted return includes the value of companies that have yet to be sold and are valued by the private equity firm, and not subject to third party valuation. Academic studies have repeatedly found that these valuations are predictably exaggerated at certain times, including when a general partner is raising a successor fund. Many general partners are in that mode now.

I suppose, when the financial system is teetering and commerce is not increasing, one way forward for a patriotic pension fund is to not ask much return on its members’ investments.