Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, has long been loaded for bear as far as financial regulations in general and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) in particularly are concerned. So one would think given his long-standing antipathy that he’d be able to make at least a semi-plausible case against Dodd Frank, particularly given that it is such a behemoth of a bill that it isn’t particularly well crafted.

Nope.

In an an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal, Hensarling laid out his bill of particulars against the CFPB, which he called a “rogue agency”. In a new post at Credit Slips, Georgetown law professor Adam Levitin shows that the claims are demonstrably false. To the extent that there have been changes in bank behavior, they can’t be attributed to Dodd Frank.

Drawing on Levitin’s post, we’ll put Hensarling’s claims in two categories: utterly inaccurate versus trumped up.

Utterly Inaccurate Claims

Fewer free checking accounts. Hensarling made a claim that is sneaky: “The number of banks offering free checking has drastically declined,” to get readers to reach that conclusion. But even with the number of banks shrinking as consolidation continues (and the CFPB has squat to do with that), this assertion is bogus.

None other than the American Association of Bankers shows the reverse, that the percentage of free checking accounts went up, from 53% of the total to 61%. Levitin points out that the CFPB can’t take credit for this, since it has done almost nada with respect to checking accounts, and the one area it did touch, remittances, is so small relative to checking account activity (many banks don’t even offer them) that it can’t have had an impact on overall pricing.

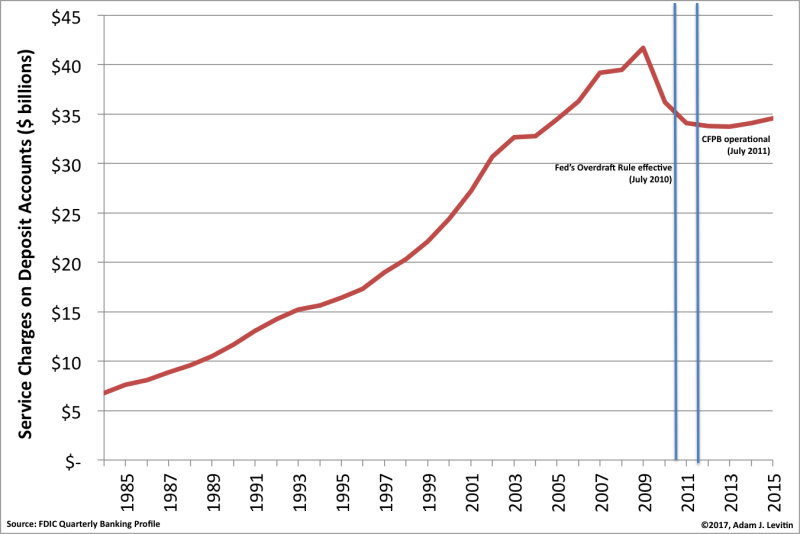

Higher bank fees. This one is particularly rich, since the CFPB is now in charge of overseeing banks for overdraft abuses, and the overall fee reductions there have to be so large as to offset anything else Hensarling might be trying to pin on the agency. Or is Hensarling weirdly trying to assert that because banks can’t gouge consumers as much with their overdraft chicanery, they are raising the rack rate of other fees?

The aggregate data refutes Hensarling’s claim. As you can see, aggregate fees on deposit accounts are almost flat since the CFPB has been in operation. Levitin does not mention that retail deposits have grown significantly over this period, so the amount of fees consumers are paying on a percentage basis has actually fallen.

Other sources not only confirm Levitin’s high level take, but contrary to what Hensarling is trying to sell, credits the CFPB with lowering fees and squeezing bank profits. It’s not hard to discern that this is why Hensarling is at war with the agency, and not out of feigned concern for consumers.

From Strategy + Business’ Autumn 2016 issue:

Noninterest income has also been flat, due to a series of postcrisis legislative initiatives that adversely affected fee-based revenue in deposit taking, credit cards, and payments. Ongoing scrutiny from the newly created Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has driven down pricing and ancillary revenues in consumer-facing businesses such as mortgages, deposit banking, credit cards, student lending, auto lending, and unsecured lending.

So in other words, the impact of the CFPB and other reforms has been not just to curb fee growth but even reduce it. And notice this isn’t just account fees but mortgage charges and auto loans, which we’ll turn to now.

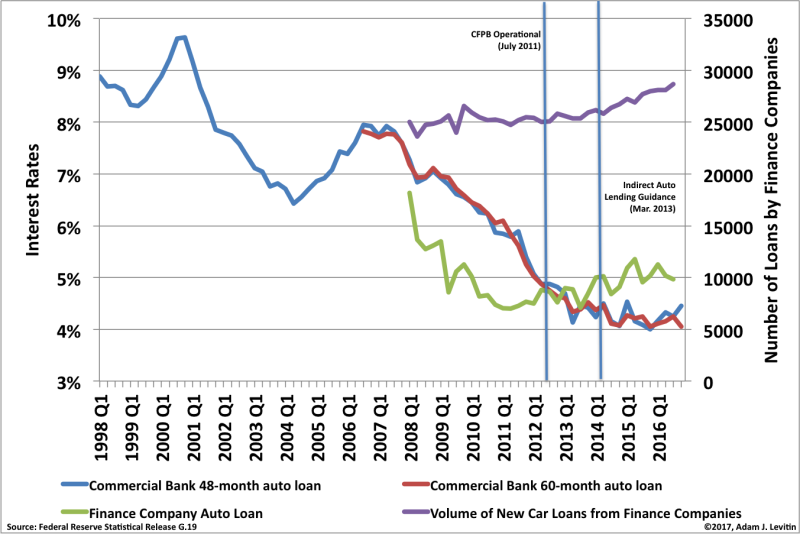

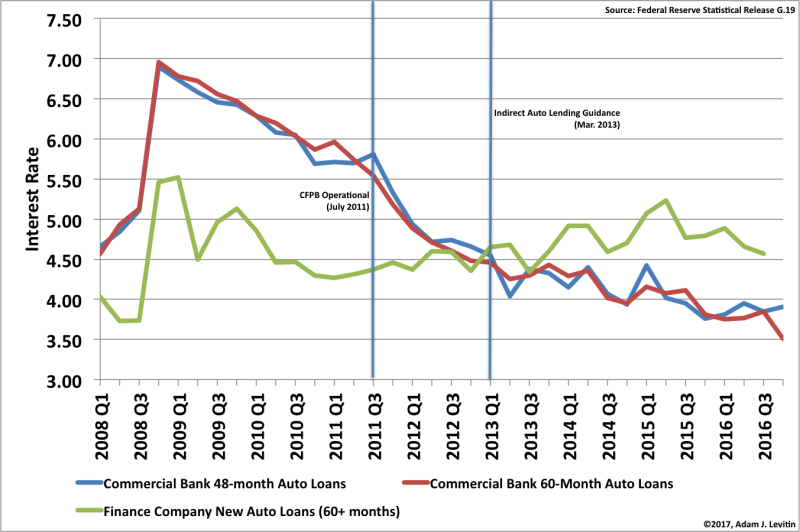

More costly auto loans. Levitin provides data consistent with the Strategy + Business analysis:

The Fed has data on auto loan pricing. Guess what. Auto loans have gotten cheaper since the CFPB came on the scene. That’s true both in absolute terms and if one backs out the cost of funds (I used Fed Funds, perhaps a 5 year constant maturity Treasury would be better, but there’s no directional difference here). In absolute terms a 48 month auto loan was at 5.89% when the CFPB went operational in Q3 2011. It was at 4.69% when the CFPB issued its indirect auto lending guidance at the end of Q1 in 2013. And it was at 4.45% at the end of 2016. The numbers excluding cost of funds are 5.81% in Q1 2011, 4.55% in Q3 2013, and 3.91% in Q4 2016. The same holds true for 60-month car loans from commercial banks. The story isn’t quite as strong for new car loans from auto finance companies (excluding cost of funds): 4.37% in Q3 2011, 4.65% in Q1, 2013, and 4.57% in Q3 2016. In other words, no real change, but lending volumes have increased, up 12% between Q1 2013 and Q3 2016, suggesting that lenders have not be constrained by regulations. Moreover, increasing volume with steady prices would indicate that if demand were held constant, that prices would in fact be down. Look at the charts below for more details. The numbers don’t lie. Jeb Hensarling is pushing a huge regulatory reform based on, um, “alternative facts.”

(The first chart is unadjusted rates from Federal Reserve Statistical Release G.19. The second chart is adjusted rates that take the G.19 data and back out the end of quarter Fed Funds rate using FRED data. I did a shorter duration because I’m lazy and things before 2008 don’t really matter here.)

Fewer banks, bankers and hiring in the economy. No joke, this is what Hensarling said:

With consumer protection outside the democratic process, consumers were harmed by a reduction in competition. With fewer lenders serving fewer borrowers, fewer businesses employed fewer workers.

This isn’t even coherent. The argument kinda sorta seems to be that the CFPB constrained consumer borrowing, which in turn reduced business opportunities. But any look at the data shows growth in consumer credit post crisis. (Levitin thinks Hensarling is trying to make the Trump argument, that regulation hurt lending to businesses, but as he points out, the CFPB has nothing to do with business lending).

As for the “fewer lenders” part, bank consolidation continues. Pretty much every expert thinks the US has and continues to have too many banks. As Levitin points out:

Yes, the number of banks has declined over the past several years, but it’s done so at the exact same steady rate of 316 banks per year that it has done for the last twenty-six years….There’s no evidence of the CFPB resulting in a material decline in the number of financial institutions, and indeed, it’s pretty hard to point to any particular CFPB regulation that would have driven anyone but a bad apple out of business. In any case, even if the number of lenders declined, there’s still plenty of lenders in the US and no shortage of lendable funds.

Levitin bothered running a regression and got an R-squared of 95%.

Trumped Up Claims

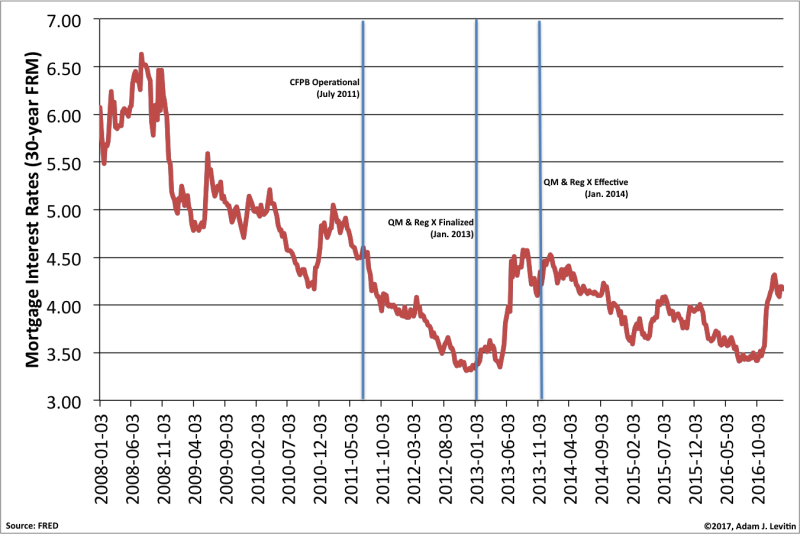

Mortgages became more expensive. Huh? Again we have weasel-wording; “Mortgage originations…have become more expensive for many Americans.” How many is many? And given the typical compliant about post-crisis mortgage lending, that originators became restrictive. The big reason was that “private label,” meaning subprime, market, is just about totally dead, thanks to the originating side refusing to accept even modest reforms while investors won’t touch the stuff without them. The lower-credit quality mortgages typically have more fees and costs than the higher credit quality ones. While Dodd Frank did impose a requirement that banks be sure that borrowers are likely to be able to repay their mortgages (what a concept!), the much bigger driver of increased origination hassle is meeting new Fannie Mae representations and warranties, plus having to cover the cost of default servicing. The CFPB has nothing to do with that.

Most people would read Hensarling’s claim as “mortgages got more pricey”. That’s nonsense:

So harbor no illusions. The reason the CFPB is in the Republican’s crosshairs has absolutely nothing to do with the impact on consumers. It’s due to the fact that the agency has managed to curb some very lucrative bank misconduct and was en route to stymieing the use of mandatory arbitration agreements. It’s now bizarrely accepted in the Beltway that major businesses should have the right to extract rents of all sorts. Trump, in attacking Dodd Frank’s tame reforms, is on board with that program.

truth to power. thanks and good luck.

The more its opponents try to gut the CFPB, the more apparent is the need for a fearless independent consumer financial regulatory authority. My major criticism of the agency is that it’s so far proceeded far too cautiously on many issues. Just one example: I wish the CFPB had issued the mandatory arbitration rule much more quickly, and crossed all necessary procedural Ts and dotted the Is– rather than faffing around with studies for far too long. Then perhaps at least a new rule would be in place, egregious mandatory arbitration procedures would have been reined in, and the rule-making wouldn’t be subject to CRA review. Instead, we’re still waiting for a final rule to be issued.