By Kevin Cashman, who in Washington, DC, and researches issues related to domestic and international policy at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Follow him on Twitter: @kevinmcashman. Originally published at The Minskys

It’s conventional wisdom among pundits that automation will cause mass unemployment in the near future, fundamentally changing work and the social relations that underpin it. Part 1 of this series contrasted this extreme rhetoric with the data that should support the inevitable robot apocalypse, and found that these predictions are likely motivated by politics or outlandish assessments of technology, not data. Part 2 assesses the technology behind these predictions, and follows a thread from the mid-20th century onwards. Subsequent parts will examine the political economy of automation in both general and specific ways, and will also discuss what the future should look like — with or without the robots.

Part 1 of this article made a case that macroeconomic data does not suggest that there is rapid automation occurring broadly in the economy nor in large industries or sectors. Other indicators, like slack in the labor market, support that assertion. It pointed to periods of rapid automation in the past as well, and found these were times with generally low unemployment and healthy job growth.

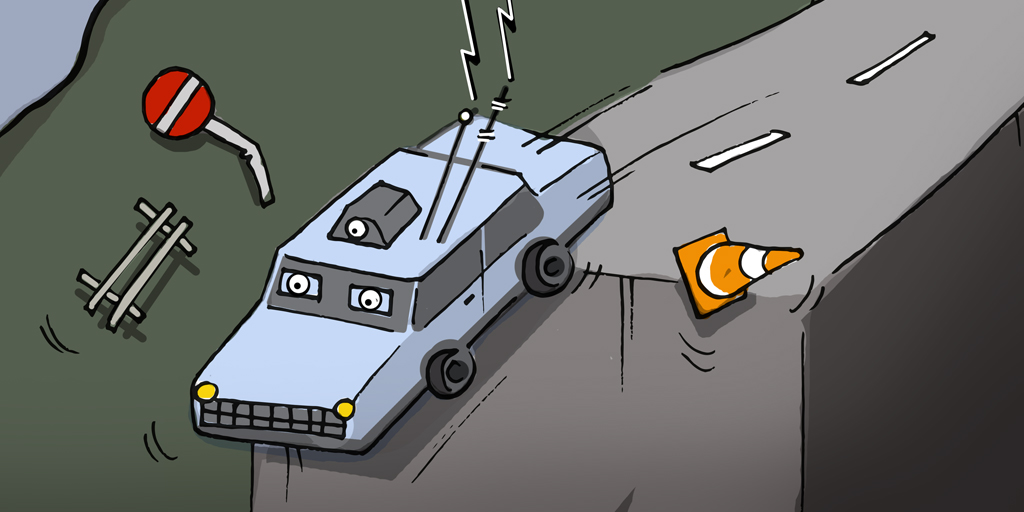

Regardless of the data past or present, there are still claims that society is on a precipice, facing mass unemployment due to wide-scale automation. Many say that the technology in the near future is different than developments that occurred in the past, and that instead of slow or moderate change that the economy can adapt to, the rate of change will be so profound that suddenly millions will be out-of-work.

There are good reasons to be suspicious of this narrative. First, it is very difficult to predict how technology will develop and affect the world, and if it will be viable or even necessary in the first place. Second, adopting new technology — for example, automating a process and replacing workers — and more importantly, the threat of adopting new technology, gives power to employers and capital instead of workers. This weaponization of technology needs to be credible in order to be taken seriously; hence, it relies on the broader narrative that rapid automation is happening. The first point will be considered now; the second, in Part 3.

The (False) Promises of Technology

Predicting how technology affect the future is a difficult endeavor. The flying cars, spaceships, and moon bases that many were sure would arrive by the year 2000 never materialized. Anthropologist David Graeber posits that technological progress did not keep up with imaginations because capitalism “systematically prioritize[s] political imperatives over economic ones.” In a capitalist system like that in the U.S., if political threats do not align with technological advancement like they did during part of the Cold War, flying cars will stay in science fiction books, he says. As the perceived threat from the Soviet Union fell away, neoliberalism’s project shifted to cementing itself as the only viable political system, at the “end of history.”

More recent predictions have remained as bold as they were in the past, but reflect this change in focus. Audrey Watters, an education technology writer, details many in her excellent presentation, “The Best Way to Predict the Future is to Issue a Press Release.” She makes the case that narratives are spun about technology for mostly political reasons or for self-interest, rather than around higher, collective ideals. Bold predictions today are about the destruction and privatization of educational institutions, technology as consumption, or mass unemployment as human labor fades into obsolescence. Pointing to the dismal track record of those who analyze technological trends — based on methods that include opaque and ill-suited taxonomies and graphs, like the one-way hype cycle — she suggests that we are actually in a period of technological stagnation. “[T]he best way to resist this future,” she says, “is to recognize that, once you poke at the methodology and the ideology that underpins it, a press release is all that it is.”

Recent evidence from the dot-com bubble lends itself to these observations. Over-enthusiastic predictions of how the Internet would fundamentally change nature of shopping — not quite a lofty aspiration to begin with — led in large part to the bubble, which popped when it became clear that these companies’ business models did not work. (For example, individually shipping very heavy bags of pet food is expensive, a fact lost onthe “innovative” owners of, and “savvy” investors in, Pets.com.) As neoliberalism was busy fashioning itself as the only ideology left standing, it served as the basis for allocating capital in unproductive ways. Whereas the ballooning of the finance sector over the last forty years is sustainable inasmuch as bankers are able to make money by creating and protecting the illusion of their usefulness, the dot-com era was a hard landing for companies that tried the same approach but ultimately could not drum up enough business to survive.

But even if past predictions are incorrect and past technological advances were limited (or had an economic potential that was much less than anticipated), the technology that is developing today could still could be extraordinary and kick off a period of very rapid automation, right? Before going further it is important to define what sort of technological developments could lead to these sorts of changes in the labor market. Often general advances in technology, or things like Moore’s law or speculation about the singularity, are used as evidence that the conditions that underlie the economy are shifting today. Here it is worth quoting directly from Economic Policy Institute’s State of Working America:

We are often told that the pace of change in the workplace is accelerating, and technological advances in communications, entertainment, Internet, and other technologies are widely visible. Thus it is not surprising that many people believe that technology is transforming the wage structure. But technological advances in consumer products do not in and of themselves change labor market outcomes. Rather, changes in the way goods and services are produced influence relative demand for different types of workers, and it is this that affects wage trends. Since many high-tech products are made with low-tech methods, there is no close correspondence between advanced consumer products and an increased need for skilled workers. Similarly, ordering a book online rather than at a bookstore may change the type of jobs in an industry — we might have fewer retail workers in bookselling and more truckers and warehouse workers — but it does not necessarily change the skill mix.

The takeaway from this should be that some technological advances that seem significant are not necessarily things that threaten jobs, change their pay or working conditions, or point to a jobless future. Technology can create new consumer products — let’s say smartphones — that seem like they fundamentally change the foundation of the economy. But they actually only shift jobs to the companies making smartphones, and don’t mean that workers making consumer products are somehow unnecessary. More significant developments like the technology behind the car or airplane can make entire industries obsolete but also can create an entire ecosystem of industries that generate wealth. Still other advancements can reduce the costs of products to a large degree so that they are increasingly used as inputs in other industries, benefiting both supplier and buyer.

These sorts of technological development are usually conflated with each other, and with the kind that is supposed to lead to mass automation and job loss. That kind of development is when very expensive robots or software replace humans completely, without spawning new industries and jobs. Two commonly cited examples are self-driving cars and delivery services. Delivery robots and drones might capture imaginations (and make for good PR) but that doesn’t mean that the economics behind them lead to a situation where workers will be replaced anytime soon.1 Self-driving car technology is massively hyped, but many think they won’t arrive in even a lifetime. Labor platforms, like TaskRabbit, a marketplace to find help with errands or odd jobs, or Uber, the taxi app, are other Silicon Valley “innovations” often lumped in with this discussion. But they don’t threaten to reduce the total number of jobs at all: they shift jobs to their platforms.

This doesn’t mean that more original uses for technology couldn’t significant impact specific sectors. However, it’s likely that, in general, technology that does affect jobs will complement those positions, replacing or changing the specific tasks that workers do, but not going as far as replacing them in all cases. For jobs that are replaced wholesale, it shouldn’t be assumed that they will disappear overnight. There still need to be decisions, investment, and planning involved in replacing workers with (usually expensive) alternatives, which are all things that take time. This has certainly been the case in manufacturing. One interesting table from the Bureau of Labor Statistics that supports this point details the fastest declining occupations. Even extrapolating out ten years, the BLS assumes that there will be significant employment in these occupations. And any changes will vary by specific industry and occupation. Even then, many “low-skill” or low-paying jobs, especially in the service sector, are not conducive to automation very much at all. (And the robots must have forgotten that those were their targets, since many of the fastest growing jobs require no formal education or only a high school degree.)

…

There’s really no definitive way to tell either way if the robot apocalypse is upon us. But the precedence for wildly inaccurate predictions; the history of technology companies being unable to deliver on extravagant promises; the fact that the technology that would threaten jobs today is more suited toward slow, incremental changes like in the past; and that the orientation of our political system is toward prioritizing political, rather than economic imperatives, strongly suggests that the robots are probably much farther off than is conventionally accepted.

Is the recent deluge of talk of disruptive technological change, ubiquitous automation, and mass unemployment a continuation of the trends and mistakes that Graeber and Watters have highlighted? It seems so, and might even be approaching the lunacy of the dot-com era. Venture capitalists pour billions of dollars into unprofitable companies with questionable business models, which are in turn valued at billions of dollars. Many of the most popular and “innovative” businesses are simply delivery services, transportation companies, or in the consumer goods industry. How many different delivery services does society need? How many different taxi apps does it need? Does anyone really need a $700 juicer, especially if it isn’t even necessary? How are these ways of doing business adding value to the economy, let alone the beginning of a jobless future? More ambitious technology has proven to been a bust, especially in biotechnology.2 One also has to question the value of recent technological assessments and predictions when many of the economic and political commentators that are doing that prognosticating couldn’t see the dot-com bubble or even the massive housing bubble that preceded the Great Recession.

The reality is that companies that are seen as the forebearers of mass automation are often unoriginal, repackaging old ideas and existing technology and using political power, venture capital money, and a lot of press releases to survive. Like Graeber said, these “innovations” seem to be more in line with boosting the prevailing economic and political ideology. Old, obsolete ideas3 like flying cars have been resurrected; for example, as part of a public relations and investment strategy to distract from Uber’s myriad scandals and disastrous finances.

If anything, the novelty of this new era of technology seems to come from the lessons business have learned from the survivors of the dot-com bubble, like eBay, Google, and Amazon:4 mainly, that business models don’t need to make sense as long as a company is able to take over a big slice of the market and change the terms of that market. In this way, vague ideas about technology and the usefulness of Silicon Valley — promoted by neoliberal icons like Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg — are used as a smokescreen for anti-competitive and anti-worker practices that seek to change the economic landscape.

Part 3 will explore an underexamined consequence of this debate: how it affects the social relations between employers, workers, and the government that are a foundation of the economy.

___________

- In this case, the delivery robots are explicitly being used to complete deliveries that don’t make economic sense for humans to complete.

- Theranos, which promised to revolutionize blood testing overstated its ability to do pretty much everything it said it could and has raised questions about similar biotechnology companies.

- Cars, flying or otherwise, have a limited role to play in cities.

- Amazon has quite a few antitrust issues and has circumvented laws; for example by refusing to collect sales tax. Google has close to a monopoly. eBay has been subject to similar claims.

“She makes the case that narratives are spun about technology for mostly political reasons or for self-interest, rather than around higher, collective ideals.”

This says it all … I follow technical change in my own field (government IT) even as I approach retirement … and the technophile hype is ever more shrill. The techno-marketing keeps telling us cold fusion will arrive any day now. It is what I would call the Popular Mechanics view of reality.

This article pushes hard to argue that advancements in technology and automation most often merely shift jobs and rarely replaces them outright. Even if automation does replace jobs, the article claims, it happens at a slow or moderate rate.

Yet it fails to include a single example of rapid, wholesale elimination of human jobs by automation.

Perhaps the most well-known example is this:

Chinese Factory Replaces 90% Of Human Workers With Robots, Sees 250% Production Increase

Another recent example from Wall Street:

Goldman Sachs Automated Trading Replaces 600 Traders With 200 Engineers

Another one from Wall Street:

JPMorgan Software Does in Seconds What Took Lawyers 360,000 Hours

In these examples the jobs that are replaced aren’t shifted anywhere — they are gone. Now, it is probably quite true that a lot of these companies touting the benefits of automation in their press releases are merely hustling to make a buck. But it is also true that in some — perhaps many — cases, automation does in fact eliminate jobs completely and it can happen quickly and to hundreds or thousands of employees at a stroke.

The article seems to gloss over that part of the story a little too easily.

It explains a little in the first part: it’s looking at economy-wide changes because these companies (and other promoters) are using basically any excuse (including ones that don’t make sense — general advancements in tech, Uber, etc.) to say that rapid automation is happening. On an economy-wide scale, the significance of robots replacing humans is probably modest or very small. And as you say, it might not be a good idea to take these companies’ words at face value.

1. The “robots in factory” example is discussed specifically in the post as the sort of oft-cited example that in aggregate does not get rid of many jobs.

2. Goldman last quarter had a profit decline based on poor trading results, in contrast to pretty virtually all other Wall Street firms that made money. This experiment looks like a bust. Algo based trading results in herding. Hedge funds started doing more algo based trading before the crisis. The quant funds failed disproportionately (including high profile funds at Goldman). Hedge funds since 2012 have become more correlated with stocks AND scoring lower performance, which has led to CalPERS deciding to abandon hedge funds entirely in late 2014 and the idea becoming popular by first quarter 2016, resulting in shrinkage of industry assets and pressure on fees.

So despite its popularity (“algo” is a sexy black box, so probably helpful in raising money), this approach is not the winner that its proponents would like you to believe (one place where it does work consistently is in “trading” of the HFT sort, which is parasitic and the SEC should and easily could shut down).

3. Pull out a calculator. 360,000 hours is all of 180 jobs at a typical 2000 billable hours in a year (250 working days x 8 hours a day).

And we only have JP Morgan’s say that the software is better. Tell me when the software is actually adopted and even these few jobs disappear. JP Morgan is not going to eat the liability of the errors its software misses. It does not say “error free” or even “makes fewer errors”. It says “less error prone”. That is an ambiguous and weak claim. And the standard for a user is not “fewer errors” which JP Morgan does not even say its software makes, but fewer MATERIAL errors.

So if the JP Morgan software makes a big error of omission that costs you money, you have no recourse based on this sales pitch. No way would I eat this risk. The JP Morgan software will be used in largely addition to, not in place of, human review.

1. Missed Part 1 so I haven’t yet read how replacing 60,000 workers with robots does not get rid of many jobs in the aggregate.

2. Just because one attempt didn’t work out doesn’t mean they won’t keep trying, because …

3. 360,000 billable hours x $250-$500 per hour = $90,000,000 – $180,000,000. (According to Forbes, associates–the partners-in-training who do much of the work at a big law office–cost $250 to $500 an hour.

As is often said here, follow the money. Replacing humans with technology and automated systems can save money — potentially a lot of money. That creates demand for technology and automated solutions, hence the gold rush mentality among the hucksters and snake oil salespersons of robotics and automated systems. Just because a lot of them are flakes and flukes doesn’t mean the underlying demand is going away.

Excellent summary Yves. I’m reminded of the recent flash crash when I hear Algo trading.

https://www.engadget.com/2016/11/09/trader-pleads-guilty-to-flash-crash/

Automation grift at it’s finest!

I don’t see automation taking over high touch point jobs, but the bigger threat to stable middle class positions is the continual degradation of formally good jobs. I work with top IP law firms and continually see a shedding of paralegal work to outsourcing firms (my company does some of this work) and the dumping of the more mundane patent prosecution costs out of junior attorney’s hands and again into outsourcing firms. The parnters continue to get richer, as do the first year associates, but the other high quality law firm jobs that don’t require a top ten undergrad or law school pedigree are definitely vaporizing and law firms work to drive down costs while also loading partners up with higher pay.

Like the kids from South Park say, “Step 3: Assume a profit!”

In my corner of the FIRE sector, the McKinsey article “The robots are coming!” got a lot of attention. Natural first reaction was to snarkily point out how well basic IT services fared with the massive move of headcount to low cost countries through firms like IBM. On reflection and considering McKinsey’s prior cheerleading of offshoring, it seems to me this too is largely about suppressing wage expectations. People can see with their own eyes that the offshore tide is ebbing and may flow the other way. Robotics (right now just enhanced VB macros) may have some applications, but I don’t think that is the primary purpose.

suppressing wage expectations

That has been the game played by US business interests for the past gazillion years and a useful tool to get Republicans elected. The robots are coming! The Mexicans are coming! The Chinese are taking all our jobs! Government regulation is eating you alive! Coal!~Obamacare! Be glad you have job and don’t be looking for any wage gains, peasants.

“Pull out a calculator.” Or more generally… “Pull out a device.”

For most people, these extenders of our brain have turned off the capacity to do critical thinking (let alone the mental math) necessary to recognize when human errors and biases are programmed into algorithms. Indeed, when algorithms are proprietary, closed off from scrutiny from those who do have that capacity, that’s when robots serve their masters most fully.

How will digital records we knowingly and unknowingly upload be gleaned by Big Data robots to distort and immortalize social and human capital?

It seems to me that as Big Data have evolved, more rungs have been removed from economic ladders of opportunity. Concentrate data. Concentrate power. Concentrate wealth.

I started out on Wall Street doing spreadsheets on green ledger paper, pulling data from annual reports, entering it by hand on the spreadsheet, and doing the computations with a calculator. And the sort of errors you get with an old-fasioned calculator are due to input errors.

It is pretty rich to compare a calculator with a “device” as in a smartphone. Calculators (save for some of their more advanced functions, like computing an IRR, which is interpolation, and NPVs) are replacements for an abacus, which is hardly advanced technology.

“do critical thinking ”

Isn’t there an app for that? ;)

Most people can’t lay out the problem in order to use a device’s power to their benefit. Think ratios and percentages.

Which is cheaper, the 24 pack of XXXX or the 18 pack? Uh the bigger one? I’m buying more right?

Not always is the answer but not the solution. To assume Walmart doesn’t play on this is naive.

I think there is room for debate here – I do think that whether or not we see actually see net job loss globally due to automation today, there is no doubt that some sectors are gambling heavy on it. It’s a “technological bluff” (Jacques Ellul). Technology has always been willing to gamble (or: capitalism has always been willing to back a technological bluff). We (someone besides the capitalists) pay the price either way: the bluff fails, we have some business failure to mop up; the bluff succeeds, we have mass unemployment and capitalist profit.

I did read part 1, and it seems to look domestically, not globally. Anecdotally I’ve met professionals in manufacturing industrees (e.g. steel) who reel off accounts of how it takes 2 workers to do what used to take 20, that kind of thing. Take it for what it’s worth. I don’t know how big an impact on the economy that is, but it seems clear that machines are displacing humans to some degree.

The Waters “The Best Way to Predict The Future is To Issue a Press Release” is well worth a quick read.

Direct focus (education) totally different but the underlying point is highly relevant to my Uber series

Sewing a garment by hand is laborious. Getting the perfect line of a machine is impossible. How much energy does it take to get a perfect line?

How many joules does it take to make my piece of garment when all externalities are included?

At which point does technology become too energy and resource intensive?

Actually research using machine vision is fixing the problem of getting the line, Automated sewing equipment is begining to arrive. The key problem is as noted. So the first things tacked are towels, pillows etc. See this web site for some details:http://softwearautomation.com/ the site says they can now do tshirts also. (about the simplest piece of clothes to sew).

Towels and pillows are one thing. Given the incredibly varied nature of human bodies, it will still be awhile (if ever) before a master tailor who can custom-tailor an article of clothing to fit an individual will be replaced with a machine.

Of course, a tailor will only be necessary for people who are concerned about the cut and fit of an article of clothing, and who can afford both the service, and clothing expensive enough to warrant custom tailoring.

Theranos for juicers:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-04-19/silicon-valley-s-400-juicer-may-be-feeling-the-squeeze

This pretty much says it all. And, if you want an even bigger laugh look at the company’s response to this outrageous “hacking” and intellectual property violation.

Talk about wasting resources. Depressing.

I usually have a glass of water and eat an apple or a couple of carrots during the day.

The first thing I cut from my kids’ lunches was the juice box.

I’ve developed a wifi equipped appliance that will insert the straw into the juicebox. $500 each. Now seeking venture capital funding.

You’ll need more than that. The VC’s are drooling over the Wi-Fi Juicer because the company gathers and sells personal information on the user – where they buy groceries, where they live, what they eat and when they eat it and God knows what other information their little machine can gather in your home and send back to them.

Just think how much tax dollars we’ll save by replacing NSA spies!

And that works just as well.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2017-03-01/i-m-renting-a-dog

The above company filed for bankruptcy yesterday in Federal Court. Dare I say it possesses everything everyone hates about your prototypical high-tech, venture-backed, financialization-of-everything startup.

To top it all off, it plies its trade on dogs and poor people, among other things. Who knew that repossessing a leased dog was an acceptable business practice? Or that making loans to poor people at 300% interest was not only legal under a lease, but also a highly profitable practice at thousands of pet stores across the country thanks to the good folks at Bristlecone.

So much of today’s new tech is simply intermediation between the buyer and seller in order to extract rent.

Goldman was probably dreaming of the day when they could take this baby public.

Does anyone do this for children? I’m thinking this could be the next big thing with the right platform and UX. You could get brand new children every 48 months! Poor people could save money by buying used children coming off lease or they could be shipped to the South American market and, before you know it, MIT Media Lab will be working on self-parenting children.

Any VCs out there please contact me directly.

Hey, let’s go further. How about Rent-a-Spouse?

You could get a new husband or wife every five years, or so, and switch. No more seven year itch. No more divorce. Get a brand new set of kids, but you could keep the old kids as relatives.

What’s not to like?

Some young people might not go for it based on a foolish belief in long-lasting love. But this market could be addressed with a simple purchase or renewal option at the end of the lease term. As I think about it, this is were you could generate obscene profits because you could charge the people who wanted to stay together a fortune!

There really needs to be a tech angle to this though. You could got to Match.com etc and sell through them – similar to the role Pay Pal played with Ebay.

Thanks for posting this article.

Interesting link to CALPERS Villalobos.

“Nevada’s public school system had just established a fund to make private equity investments in local businesses.” Is this happening in other places??

We’re only in the beginning of the automation of the office work. So far what has been done is deskilling of many jobs.:

-Who needs to know how to spell when there are easy to use spell-checkers?

-Who needs to know how to count when there are easy to use accounting packages and calculators?

-Who needs to know how to be organised when company provided software organises the worker day?

-Who needs to have good judgment when the algorithm is the sole decider?

Admittedly the above will first and foremost hit the junior positions but give it time and algoritms will slowly find their way up on the organisational ladder.

The factors holding back the job-losses are:

-Bad implementations. I’ve seen companies increase their workforce and achieve worse results due to bad implementations.

-The de-skilling of the jobs puts downward pressure on wages so why bother with algorithms and risky implementations if it is cheaper to just hire more?

And lets not forget, the problem (for most) isn’t that tasks are being automated away – the problem is the loss of income due to reduced bargaining power from the increased use of algorithms.

As for ‘the reality’ in the above quote….. That is only ‘the reality’ for people in think tanks, the rest of us experience reality – slow incremental changes continuosly reducing bargaining power leading to reduced earnings.

Yeah. Systematizing, standardizing and removing variation are vital parts of automation. Thorsten Veblen pointed this out in his discussions of the machine process. You won’t need people who can spell once you’ve standardized away the need to read. You can do this if you boil the process down to the point where simple response to cues is enough.

“The reality is that …” is one of the things that made me feel that this article is really shaky. Of course those are the lead companies in automating. Those are the companies where radical standardisation can happen first. It’s parallel to Jane Jacobs’ point (Cities and the Wealth of Nations) about transplanted industries, that are simple, or “smooth” enough to be cut out of their original industrial ecologies and dropped in someplace else. Argument by sneering — that these aren’t important companies, that these aren’t the real neat companies — kind of leaves me cold.

“-Who needs to know how to spell when there are easy to use spell-checkers?”

As somebody who works at a printing company that does a lot of small jobs for local companies and organizations my answer would be apparently everybody. So many errors on documents that should be getting extra attention that it is a running joke at my office as to the basic skills of our salary class masters. I guess those spell checkers are unknown to them or beneath their pay grade to use.

Heavy factory automation in the US and Europe has been possible for some time . We’ve had the software and hardware to fully automate some factories for some time, that is, to have a few workers and a lot of machinery generate very large revenue, such as producing cars.

However, it’s interesting that this hasn’t happened, even though it can be done.

There are probably several explanations for this delay, or failure [?]. One guess is that outsourcing, immigrant workers, and China-ization have driven down wages so that heavy automation isn’t yet necessary or feasible. In other words, the economics isn’t there at this point. If this is true, then heavy or full automation is being saved for the day when wages rise substantially and automation therfore becomes desirable, perhaps necessary.

So low wages have warded off automation, so far, if that explanation is correct.

Contrast this with loan and mortgage operations up to the 1970s which required two or more layers of approval by humans. By the mid 1980s algorithms [ie, multiple regressions] quickly replaced human judgment in evaluating mortgage or loan requests. At this point a bank can qualify you for a mortgage in five minutes or less by getting your credit rating on line.

So these two stories seem to indicate that pace of automation depends on the industry and its forces.

Ted was right.

A recent horror story of “automation” gone awry has just occurred in Michigan. The majority of human employees at the Michigan (doesn’t) Works! agency were replaced with an automated computer system. This system proceeded to arbitrarily, and wrongfully, accuse thousands of Michigan workers of criminal fraud and lead to them having their wages, bank accounts and tax refunds stolen by the State of Michigan in repayment of a crime they never committed. Worse than that even, when these poor victims actually managed to get a human being on the phone all they were ever told was “Yes. Our records show you committed fraud.” The robot has decided.

I rather suspect that the usual hype is actually deliberately presenting the argument the wrong way round.

If you begin from the desire to make higher profits by employing fewer people, then you will develop arguments that automation necessarily destroys jobs, rather than looking to see how you can make use of the workers elsewhere.

In any case, as the article suggests, the basic premise is flawed. People have been saying that we live in a time of unprecedented technological change for at least a century and a half now, and in the past it was truer than it is now. If you were born in 1840 and died in 1920, the world would have changed beyond your capability to comprehend. If you were born in 1940, and die in 2020, the main impression you’ll have is how little things have changed. The computer, the passenger jet, television, the space rocket and the automated production line would all have been familiar to you by the time you became an adult.

For a bracing corrective to such futuristic fantasy see David Egerton’s book “The Shock of the Old.”

Once they automate life-like love dolls it might be the end of the human race. . .

I met a flaky woman

Told her to go away

She said, “The bros arent comin’ to me”

I said “You wanted it that way”

Now my doll’s love is good lovin’

I take all that I can get, mmh

Oooh, oooh she looks at me with those electric eyes

And says,

You ain’t seen nothin’ yet

B-b-b-baby, you just ain’t seen n-n-nothin’ yet

Here’s something that you’d never ever get

B-b-b-baby, you just ain’t seen n-n-nothin’ yet

And now I’m feelin’ better

‘Cause I found out for sure

I don’t need no doctor

Right here I got the cure

Because any love is good love

So I take what I can get

And now she look me with them big electric eyes

And says,

You ain’t seen nothin’ yet

B-b-b-baby, you just ain’t seen n-n-nothin’ yet

Here’s something that you’d never ever get

B-b-b-baby, you just ain’t seen n-n-nothin’ yet

-with yuuuuge apologies to Bachman Turner Overdrive for the lyrical grifting

Thanks for this. Personally I’d say the people who worry so much that the robots are coming to get us watch too many movies. In the real world if you totally subtract the human element then there will be nobody to buy the products and the companies will no longer be able to afford those expensive machines. It becomes a self-correcting loop unless one assumes the machines are going to eliminate us all, Terminator style. Far more likely that we blow ourselves up before that ever happens.

Or teebee shows that have nice robots intended for family viewing.

I’ve already decided where this is all headed. In 2025 we’ll have the “Lost In Space” robot replicated on every street corner handing out Jehovah Witness pamplets, waving his arms in the air frantically, and proclaiming, “Warning [Will Robinson]. The world is coming to an end!”

The greatest of all Transformational innovations that I know of has been cars. They moved right into the livery. The stables were filled with automobiles. Think of “The Rievers” by Faulkner, and as a movie how much Steve McQueen loved that automobile. Cars, were loved.

In our lives there have been no lovable robots. There were some in the movies, “Danger Danger” spoke the robot friend in “Lost in Space”. RDD2 was nearly an identical robot friend in “Star Wars”.

I have mentioned before that my airplane mechanic friend simply said, “I’ll never be out of a job, everything breaks.”

There are people who are in a position to love robots, say Jeff Bezos for instance. So far most of us do not have a robot to love nearly the same way as we all got a chance to love our cars.

It is not that they have not been transformational on factory floors & the assembly lines, it is that not yet has one come into our lives the same way as the Ford.

If I was the CEO of Clark I could make it so by putting along side the ubiquitous forklift the exoskeleton.

However as a transformational thing it is likely to stay there more than ever so much in the home, in the driveway. I mean that the robots that are integrated into our lives will be limited in their orbits for materials handling & assembly or to help in hospitals & augment crutches & wheelchairs.

(The DARPA exoskeletons are intended for moving artillery shells.)

If Robots ever get souls it will be in outer space where they will live better lives than we ever will. When Mars is populated it will be for robots who we intend will remember us.

Of the great Transformational machines I have strong doubt that any will ever beat the car.

The driverless car? Well it sure does mean for one thing, that driving is no fun anymore.

I thought the most interesting insight above was the one about spending for “political” projects but not for economic ones. This is almost saying spending is always allocated to the military and the MIC but not for social projects. If infra is a national interest then infra it is. If preventing a social uprising of a deeply deprived underclass, then spend away. And all the new tech comes from this “political” investment as it spins through various applications that can be considered consumer products, etc. This is the old Cold War model of stimulating the economy and it wasn’t a bad criterion – invest in whatever technology makes the country more invincible. This is the original trickle-down. War itself may become obsolete, but technological applications of basic science projects will always be a good thing and unlikely to produce a frivolous technological economy, frivolous stuff goes extinct pretty fast. I almost look at this assessment as a ray of hope because the environment is undeniably of national interest. Global warming is a pending disaster of the first order. And, ta-da – we have the perfect vehicle to invest to protect against these conditions. The military. Let’s use it.

Who else came here to find out the best place to buy cat food online?

Stupid clickbait article..

You are accumulating troll points with comments like that. Anyone with a adequate reading comprehension or having had their AM coffee if that is what they need to be alert could see with the words “grift” and “flying cars” what the article was about.

The two dots after “article” triggered my snark detector. But I’m sensitive, and get false positives, too.

yeah, I knew it was borderline. Duly noted, Yves.

Another excellent post trying to debunk the “technology hype” for what it is namely a hype only.

Two things though that may be addressed in part 3 but I can mention here:

1. There is ulterior political motive behind this seemingly reckless misallocation of resources and capital to what could be described as psychotic delusions of a oligarchic cronies from Wall Street and SV. It is much more insidious than that I am afraid.

The fact is that those like UBER and others speculators from Wall Street, SV etc., are not betting on new “mass” transportation system, or industrial system with robots instead of people, not at all, they are betting on disruption (in a way of crippling existing transportation systems to make it look dysfunctional) and using the hype of fashionable “creative destruction” lie to destroy the legacy systems only to achieve their true objective namely to repeal a slew of existing labor laws in the US and globally and re-create nothing but “digital” neo-feudal labor arrangements calling them “sharing” economy what should have been called old servant economy with iPhones. It is an exemplification of race to the bottom for wages and incomes as a method of maximizing the profit under guise of technological progress which in fact it is not.

They want to destroy concept of employment in itself and are looking to go to high courts (SCOTUS in US) to repeal the existing labor laws by bribing right-wing/neolib radicals on the courts. It is happening now.

In this context, what’s really amazing and disturbing is what’s corporate propaganda done to younger people. Amazing, what classical Orwellian, newspeak did to basic understanding of what going on around them.

The false narratives of this insidious propaganda of freedom, liberty, flexibility or “free choice” etc., all Orwellian constructs devoid of their true meaning have been unleashed onto entice younger gullible iPhone generation to willingly give up on basic labor rights that workers, often their ancestors, fought with their blood sweat and tears for centuries.

And for what? For nothing, but some false promise, and fake chances of better life as a modern corporate serf, a feat resembling giving away loosing lottery tickets to destitute.

Praising flexibility and supposed choices, people are not realizing that accepting this, is nothing but abandoning hard fought unalienable rights to specific apriori agreed working hours limited to maximum eight/day, specific apriori agreed working days, specific apriori agreed pay rate or total pay/month, not to mention other benefits, such a paid sick leave when injured, prohibition of child labor, protection of unions, protection of health and safety and retirement at old age when worker is unable to perform duty and much more.

All those achievements are clear to see for anyone who ever bothered to read any Dickens novel. Unfortunately not many did.

2. The digitization/robotization like XIX century mechanization of manufacturing industry has been promoted and developed as a direct threat to working class not as a popular economy books tell us, a benign improvement of efficiency or even increase of profit. It was not its primary goal.

Examining history clearly explains the situation of suppose loss of jobs due to machines in the XIX century an age of industrial revolution as a deliberate political act not an inevitable wind of progress or even economic advancement.

At that time KOL (Knights of Labor) in the US and trade unions across the Europe were also facing so-called technological “progress” aimed directly and solely for engaging smarter machines/technologies and dumber workers so their pool can be widen to less skilled workforce including women and children, and easily interchangeable to keep wages low.

The condemned as unreasonable by establishment economists at that time, practice or a strike tactics of disabling/destroying machines was widely used not for futuristic reasons of a unspecified “threat of machines” but so no costly, difficult and dangerous occupation strikes had to be organized fighting the capitalists/corporate owners while easily found by the management strike breakers could not be used to restart production in a short term giving workers a better negotiating leverage.

I look forward to read part 3.

I found here an interesting take of “disruptive innovation” namely what it really means in a etymological and historical context.

https://sostratusworks.wordpress.com/2015/10/18/the-age-of-disruption/

In the coming Brazilianation of the DM countries why would the owner class bother with complicated, fiddly robots that need to be maintained by expensive techies when they can simply import countless extremely docile EM drones who when used up will be ejected back home…

There is going to be an endless supply of these people. Africa is projected to go to 4 billion people by 2010.

What year is it now where you are?

2100. A typo it is called :-)

The rise of delivery upstarts and the decline of brick and mortar retail has as much to do with the decay of the transportation infrastructure as any new technological upheavals. Driving is a PITA nowmost everywhere. If it were not the delivery value would not carry the same premium.

Shopping stinks. It’s a combination of:

1) Driving (gas prices ain’t cheap, takes valuable time to get to your destination)

2) Parking in the poorly designed lot

3) Go into the store and they don’t have inventory

4) Try to ask for help and discover that the store is woefully understaffed and those that are on the clock are clueless

5) Price discovery. The other day someone snarked about showrooming and really what showrooming tells you is that buyers now have price discovery and see no reason why a TV that is $375 on Amazon lists for $500 at Best Buy other than the 7 and 8 figure salaries for their executive team and the ever-popular shareholder value. Buyers rightfully balk at paying extra so the top execs can make their bonuses/numbers. Any commodity available on Amazon will ultimately be destroyed as a brick and mortar business model.

I think the misunderstanding comes from the expectation that the takeover of automation will happen quickly. In fact it will happen slowly and we will not understand what is happening, like a frog being boiled.

The truth is that the low hanging fruit of automation has already been picked. Food processing, CNC machining and bank back office operations are now fully automated and have been for decades. What remain are a myriad of smaller applications, like McDonald’s burger flipping machines, having lower payback. These will be automated slowly but inexorably over the next decades.

We may after all end up selling each other insurance. We are well on our way.

Maybe we need a new “financial product” that insures us against being replaced by a robot.

An alien visiting Earth for the first time would not understand this debate. Automating the production of everything should be an overwhelmingly good thing. Our problem is that we don’t know how to share the benefits.

For me, the fact that Nichols and McChesney are on board ameliorated some of the sense that this theme was a grift. They called their book People Get Ready. Haven’t read it, but I listened to a couple of their recent talks. I respect them from their other projects, such as Nichols on Wisconsin and McChesney and both of them on media consolidation, media history and so on. It seemed in their talks as though they were a little exhilarated that unemployment could be radicalizing. They seem like they are anticipating a lot of “reproletarianization”. So they were exhorting their audiences to fight the smug tech-superiority and its spokespeople – but this suggests that they think there is something big underway, and that it is not overhyped. I know we talk about Overton Windows on NC, so I recognize that I may be falling for the left end of something. Nichols and McChesney can interest the labor left and someone else can interest the Schumpeter-right. Put them both together and you have dominated the range of opinion. Am I stumbling into something like that? Have the critiquers addressed Nichols/McChesney? Thanks!

“Anthropologist David Graeber posits that technological progress did not keep up with imaginations because capitalism “systematically prioritize[s] political imperatives over economic ones.”

Perhaps, to some extent. But also there is that part about the future being so unpredictable.

Human intelligent robots, a staple of science fiction for nearly a century, are still not here, and might not be for a while. And yet virtually without exception, pre-1960 science fiction never had the slightest inkling of the raw computational power of modern electronics. Not even close! Our modern internet was literally beyond imagination.

As late as 1977 in the novel “gateway” the author posited that the computing power of the ENTIRE WORLD would consist of a ‘gigabit space.’ That is 125 megabytes. For the world.

We can now make antimatter – OK, not a lot, but we can. Not that long ago we didn’t even know what that was. Adaptive optics, genetically modified organisms (for better or worse), … you just never know how it will all turn out.

I’m lost in my efforts to understand the intention driving the arguments in this post about automation.

Is there incredible hype and hyperbole in the claims about automation and the claims of job losses or job gains? — hardly needs saying that there is. Have predictions about the future been grossly in error? Keynes predictions of problems dealing with too much leisure come to mind. Automation is applied for many reasons and not all of those reasons are matters of efficiency or simple replacement of workers. And:

“… significant developments … can make entire industries obsolete but also can create an entire ecosystem of industries that generate wealth”

“There’s really no definitive way to tell either way if the robot apocalypse is upon us.”

OK — SO WHAT!?

One day automation and another day out-sourcing and immigration are blamed for the loss of jobs, loss of income — loss of place in society for growing numbers of people. Arguments about automation are in the vogue along with arguments about out-sourcing and immigration. Worker education and worker training is another favored mode with lack of worker flexibility, willingness to move, to accept lower pay, to successfully “compete”. The arguments play in harmony, counterpoint, consonance and dissonance with each other. But no matter what tunes the piper plays jobs continue to worsen and money and power continue to flow to the wealthy and our society, our country, our culture disintegrates right in front of our “lying” eyes.

I can’t forget how wrong Keynes was about our future. But it seems to me neither automation nor outsourcing nor immigration nor other favored whipping boys bring us closer to a root cause to which we might apply meaningful remedies.