Yves here. I’m running this post for several reasons. One, economics routinely ignores history, including the history of its own ideas. For instance, Adam Smith has been hopelessly cherry-picked to the point of misrepresenting some of his important observations. But second, this post conveys the notion that businessmen re-investing in their communities was a type of charity, as opposed to good business or (horrors!) a corporate duty.

The authors seem oddly ignorant of the fact that the idea that companies should maximize shareholder values is an idea promoted by economists, and not a legal duty. Moreover, it is a comparatively recent idea and conflicts with older ideas of the responsibilities of corporate officers and board members.

From a 2014 post:

One of my pet peeves is the degree to which the notion that corporations exist only to serve the interests of shareholders is accepted as dogma and recited uncritically by the business press. I’m old enough to remember when that was idea would have been considered extreme and reckless. Corporations are a legal structure and are subject to a number of government and contractual obligations and financial claims. Equity holders are the lowest level of financial claim. It’s one thing to make sure they are not cheated, misled, or abused, but quite another to take the position that the last should be first.

If you review any of the numerous guides prepared for directors of corporations prepared by law firms and other experts, you won’t find a stipulation for them to maximize shareholder value on the list of things they are supposed to do. It’s not a legal requirement. And there is a good reason for that.

Directors and officers, broadly speaking, have a duty of care and duty of loyalty to the corporation. From that flow more specific obligations under Federal and state law. But notice: those responsibilities are to the corporation, not to shareholders in particular…Shareholders are at the very back of the line. They get their piece only after everyone else is satisfied. If you read between the lines of the duties of directors and officers, the implicit “don’t go bankrupt” duty clearly trumps concerns about shareholders…

So how did this “the last shall come first” thinking become established? You can blame it all on economists, specifically Harvard Business School’s Michael Jensen. In other words, this idea did not come out of legal analysis, changes in regulation, or court decisions. It was simply an academic theory that went mainstream. And to add insult to injury, the version of the Jensen formula that became popular was its worst possible embodiment.

One good source for the fact that economists, rather than legal decisions, were the basis for the acceptance of this idea, is a 2005 article by Frank Dobbin and Dirk Zorn, “Corporate Malfeasance and the Myth of Shareholder Value.” This paper looked back to the 1970s, the era of diversified and often underperforming firms (remember the conglomerate discount?). Deregulation, high inflation, and a lax attitude towards anti-trust enforcment stoked a hostile takeover boom. Economists celebrated this development as disciplining chief executives and moving assets into the hands of managers who could operate them more productively. In reality, the success of these early deals depended mainly on asset sales, both of non-core operations and of hidden sources of value, like corporate real estate, as well as leverage and slashing bloated head office staffs (the across-the-company headcount efforts became more prominent in the 1990s).

But I’m now reading an advance copy of terrific book, Private Equity at Work by Elaine Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt, which adds important detail to the Dobbin and Zorn’s account. It’s done a remarkably impressive job of marshaling data about the private equity industry and explaining how it operates, which means debunking its claims about how it adds value. And even its asides are rigorous. For instance, its four page treatment on the origins of the “maximize shareholder value” line of thought showed real mastery of the source material.

Appelbaum and Batt trace the origins of the managerial model of capitalist enterprise to the New Deal securities laws. They helped institutionalize dispersed shareholding, and with it, a separation of ownership and management. From the 1930s onward, there was an active debate between two schools of thought. Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means were concerned that this new approach neglected shareholder interests. By contrast, Harvard law professor Merrick Dodd contended that large-scale corporations had broader social aims, including providing employment and useful goods. By the early 1950s, the Dodd view had clearly prevailed.

Although the writers of that era would never have used this framing, large corporations created reasonably efficient internal markets. Both employers and their workers benefitted from investing in a workforce that was also their main source for supervisors and managers of all levels. Indeed, middle and senior level executives hired in from the outside often found it hard to adapt to these well-established, tightly knit corporate cultures (note that well-established does not necessarily mean “well functioning”). The tendency of companies to promote from within versus the generally lower odds of succeeding in another company meant that most employees’ best prospects were within their current company, which gave them strong incentives to make it successful.

This was also the era when unions had clout. That assured that productivity gains were shared among workers, management, and investors. The fact that labor participated in these improvements helped propel a robust consumer economy, fueling more business growth. These enterprises typically took a long-term view, and used retained earnings to fund investments and research.

This model prevailed until the 1970s. Even though corporate profits as a percent of GDP grew in the 1970s even under stagflation (after the oil shock recession of 1974-5 had passed), return on capital had plunged from 12% in 1965 to 6% in 1979. Appelbaum and Batt describe the rise of the diversified corporation as one of the biggest culprits. They’d become popular in the 1960s as a borderline stock market scam. Companies like Teledyne and ITT, that looked like high-fliers and commanded lofty PE multiples, would buy sleepy unrelated businesses with their highly-valued stock. Bizarrely, the stock market would valve the earnings of the companies they acquired at the same elevated PE multiples. You can see how easy it would be to build an empire that way.

But these sprawling conglomerates had lots of managerial downside. Top brass often didn’t understand the operations of these new businesses. They became more dependent on finance staff to impose metrics across businesses to have a handle on what was going on. The formerly virtuous internal labor markets became balkanized and less salutary. And at a higher level, the various businesses were more likely to operate like fiefdoms competing for corporate resources. Finally, because the top executives treated these units as portfolio holdings that could be sold at any time, they were less certain of the necessity and value of investing in them.

Back to the current post. One way to think about this history is that it illustrates one of the many problems of the idea that a promise as ambiguous as equity can and should be sold on an anonymous, arm’s length basis. Owning a stock means only “We’ll pay you dividends if we make enough money and are also in the mood. And yes, you have a vote, but we can dilute that when we feel like it.”

Historically, equity investors were more like venture capitalists: they invested in companies where they knew the management personally, were kept appraised about the strategy and results, and often played an active role in promoting the venture. By contrast, even thought the US securities laws of the 1930s were designed to make investing in such dodgy securities as stock safe for arm’s length parties, the truth is that public companies, as professor Amar Bhide described in 1994, always suffer from deficient governance. Anonymous and transient shareholders will never be able to have the access to management and operations to make an informed assessment of how good they are. And public companies can never share much information about their strategies and plans because they are competitively sensitive.

To return to the theme of this post, another oversight by the authors is not considering that other cultures also define the duties of company-operators differently than Anglo-American norms. For instance, in Japan, the top priority is creating/preserving employment rather than profits. During Japan’s lost decades, company executives, who were never lavishly paid relative to low level workers, compressed pay of middle and senior managers and top executives to keep firings to as low a level as possible.

By Catherine Casson; Mark Casson, Professor of Economics, University of Reading; John Lee, Research Associate, Centre for Medieval Studies, University of York; and Katie Phillips, PhD student in Medieval Studies, University of Reading. Originally published at VoxEU

Community engagement and responsible use of profits are issues of increasing concern to contemporary businesses. While interest in these issues is often seen as a recent phenomenon, in fact it has medieval origins.

Profit and community were reconciled in the Middle Ages in a way that we can learn from today. Medieval merchants believed that their pursuit of profit should promote the common good of the communities where they lived and worked. They re-invested profits from their business activities into philanthropic projects.

England in the Late 13th Century

England in the late 13th century had a dynamic economy (Britnell 1993). Manufacturing and service sectors existed alongside agriculture (Hatcher and Bailey 2001). National and international trade was conducted by enterprising merchants, aided by new institutions that lowered transaction costs. Legal advances created a lively property market and commodity trade while improvements in water management and bridge-building aided transport and infrastructure.

Towns grew dramatically, both in number and size. The period from around 1200 to around 1350 is now recognised as a period of commercial growth that was as significant as the later Industrial Revolution (Britnell and Campbell 1995).

Individualistic capitalism was not the basis for this 13th century expansion, however. In contrast, family ties and community loyalty were strong. Successful entrepreneurs used their new-found wealth to support their local community. They invested in new infrastructure to improve transport links and security and financed hospitals to care for the poor and infirm (Casson and Casson 2013, 2014).

New Evidence on Medieval Cambridge

Using recently discovered documents on medieval Cambridge, we have investigated how money was made through property speculation and how the profits of successful speculation were spent. Our analysis is based on over one thousand properties recorded in the so-called ‘Second Domesday’ – the Hundred Rolls of 1279 (Maitland 1898, Raban 2004).

Property markets developed in medieval England as burgage plots were laid out in new or expanding towns by local landowners (‘lords’), with the king’s permission. To acquire a plot, a burgess had to pay a perpetual rent and erect a building conforming to local plans. He could bequeath or sell his plot. Capital gains could be taken as lump sum payments or as an additional perpetual rent paid to the seller (Goddard 2004). Plots returned to the rent-recipient (e.g. the lord) if rent was not paid (Holt 2010, Keene 1985).

While the operation of commodity markets and local trade during the commercial expansion of the 13th century has been explored by economic historians, the operation of the property market has been under-researched in comparison. Our research combines statistical analysis of medieval records with detailed analysis of the backgrounds of the individuals and institutions that developed property portfolios. We identify patterns in rents, highlight strategies used to assemble property portfolios and examine how the profits of property speculation were spent (Rubin 1987).

Cambridge in the 13th century was not yet a famous university town, but rather an inland port whose merchants specialised in wholesale agricultural trade (Lee 2005). The town had origins dating from at least the 10th century, and in 1068 a castle was constructed there, followed by three religious houses in around 1092, 1133, and 1203. The River Cam provided a navigable network of waterways to Ely, Peterborough, and Huntingdon, and to ports at Wisbech and Lynn.

At the time of the Hundred Rolls, visitors from London would enter through the Trumpington Gate, with the King’s Mill to the left and the King’s Ditch on the right. Heading north, the visitor would enter the business district, with the market to the right, just behind Great St Mary’s church – one of 14 churches in the town. On the left would be buildings later demolished to make way for King’s College Chapel.

Continuing up the High Street past the Jewry would bring the visitor to the Round Church. On the left would be Hospital of St John the Evangelist, later re-founded as St John’s College (Lineham 2011). Continuing to the Great Bridge (now Magdalene Bridge) the visitor would pass St Clement’s Church, through the area where the wealthiest people resided. Passing over the bridge would provide a view up the River Cam of the great stone house (now called the School of Pythagoras) where the influential Dunning family lived.

The visitor would then ascend the Huntingdon Road, with the castle (now a mound near Shire Hall) to the right and views over the grounds of St Radegund’s Nunnery (now Jesus College) towards Barnwell Priory. A walk up the Newmarket Road would lead to hospital of St Mary Magdalene with its chapel (still standing today), and the site of Stourbridge Fair (Zutshi 1993).

Property Hotspots in Medieval Cambridge

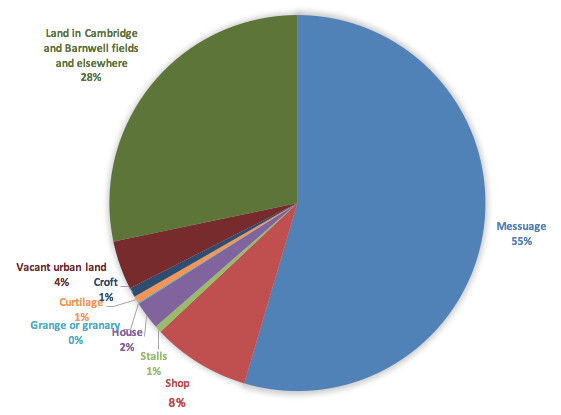

Property was a desirable asset in medieval Cambridge, much as it is today. Medieval speculators invested in a variety of properties (Figure 1). Land was popular, including fields, curtilages (the area of land around a building), vacant urban land and crofts (land adjoining dwellings, often used for agricultural purposes).

Buildings were also invested in, both residential (messuages – houses with land and often outbuildings – and houses) and commercial (shops and stalls – usually temporary structures in marketplaces). Statistical analysis of the levels of rent shows that messuages and shops were the most valuable properties.

Figure 1 Types or property

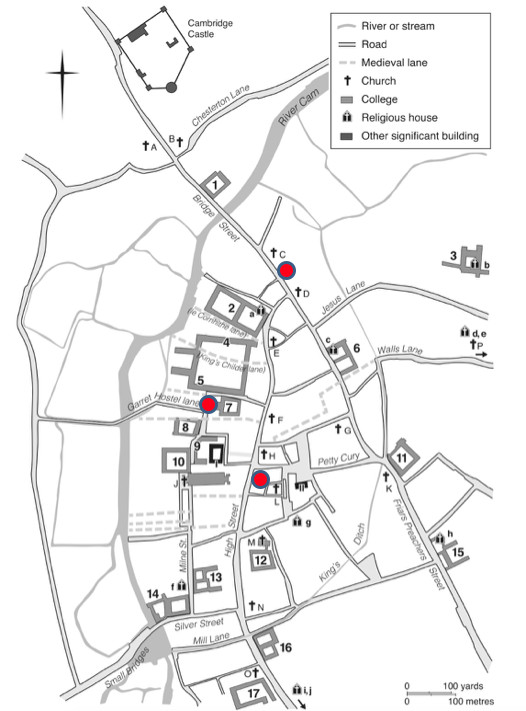

Property hotspots with high-rents can be identified in three parts of medieval Cambridge: at the road junction by the hospital; west of the market; and near the river just south of the hospital (Figure 2). Areas of notably low rents were near the castle, the area of Trumpington Street, and the suburb of Barnwell.

Figure 2 Map of medieval Cambridge showing property hotspots

Source: Adapted from Lee (2005).

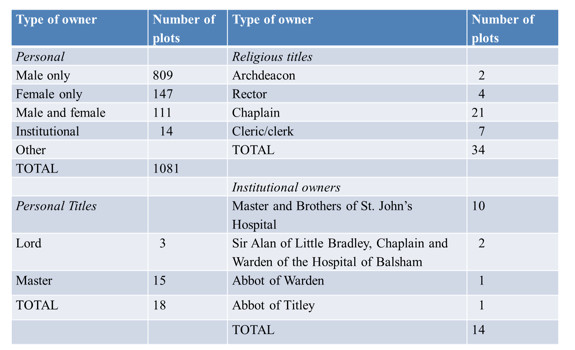

Individuals and institutions both owned property (Table 1). Family bonds often underpinned ownership. Cambridge was home to several families who had acquired property through the military service of their Norman ancestors, including the Dunning family who owned 12 plots in 1279. Property was passed down through generations. The Wombe family benefitted in 1279 from a portfolio amassed by an ancestor (Hundred Rolls, Roll 1, folio 3). The commercial revolution posed some challenges for this ‘old money’. The Dunnings mismanaged their assets and eventually left Cambridge (Gray 1932).

Table 1 Types of (rent-paying) owners

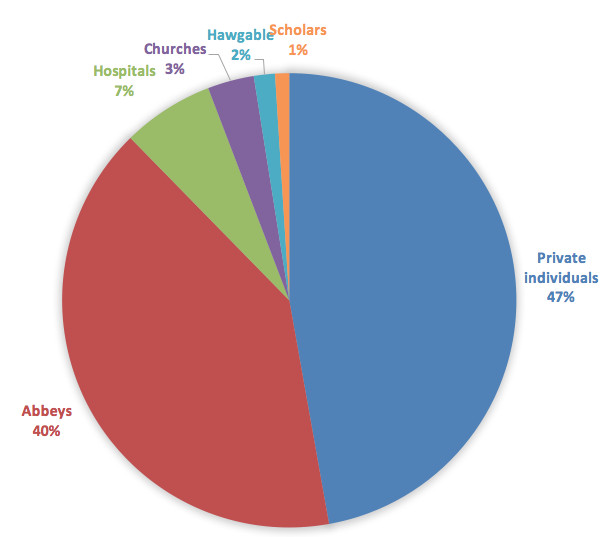

Profits from the property market were recycled back into the community through donations to religious houses, hospitals and churches. Owners allocated more rental income to charitable giving (51%) than to private individuals (Figure 3). The Barton family, for example, were important patrons of The Crutched Friars and the Nuns of St Radegund’s while the Dunnings gave land to Barnwell Priory, the Hospital of St John and St Radegund (Gray 1898; Miller 1948; Underwood 2008).

Figure 3 Types of recipients of rental income

The Black Death and its Aftermath

The Black Death and its Aftermath

The 14th and 15th centuries brought new challenges. The catastrophic outbreak of plague in 1348-9, known as the Black Death, probably halved the population. Major Cambridge landowners, including Barnwell Priory and Corpus Christi College, were attacked during the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381. Properties were cleared and streets obliterated to create a new site for King’s College Chapel during the 1440s.

Yet the townspeople continued to make gifts to the monasteries, friaries, and the hospital of St John, and increasingly to new institutions, the religious guilds and the colleges. New academic colleges were founded and the university grew in size and stature, helping Cambridge to weather the economic storms of the later Middle Ages, and laying the foundations for the town’s later prosperity (Lee 2005).

Profits from property speculation benefitted individuals, family dynasties and the urban community as a whole. Compassionate capitalism involved high levels of charitable giving to hospitals, monasteries, churches, and colleges, which helped to disseminate the economic benefits of the ‘winners’ of the commercial revolution.

This self-sustaining system, however, faced challenges due to social upheaval after the Black Death, and the increased financial burdens placed on merchants and towns in order to fund warfare in France. When prosperity returned in the Tudor period a more ruthless form of capitalism took root, whose legacy remains with us today.

See original post for references

I think that corporations’ sole mission should be to maximize profit, and that any notion of “community support” can be best and most fairly satisfied by paying taxes they could otherwise offset or offshore. There is no “community-friendly” corporation. Corporations’ involvement in the community is a conduit for corruption.

With all due respect, you made clear that all you are offering is a personal opinion. As we stated at some length, your opinion has no foundation in law. Equity is a residual claim in a corporation. Creditors, like lenders, suppliers, employees, the tax man, as well as contractual obligations and regulations come before shareholders.

Unfortunately law that isn’t enforced, has no way to improve the commonweal, assuming it is even designed to that object. Corruption is what we call the ability of counter-parties to exploit the tragedy of the commons … and it usually ends with enclosure and emigration. In those times, the king had little ability to tax, hence Runneymede … which was the scene of the attempt to prevent King John from taxing the barons beyond the ordinary requirements of vassalage. The major impact of the national government was the bloodletting of endless warfare, like the Battle of Towton. Though remunerative opportunities as a mercenary in France was nearly as endless.

The “tragedy of the commons” is basically a myth. It’s a thought exercise for history-ignorant economists. Lambert has posted several times on real world examples of resources held in common and the complex network of community-respected rules that formed around them. Naturally, in modern times the idea of the commons has become so divorced from historical practice that commons are almost inevitably stolen and exploited for the short-term benefit of the wealthy.

The “tragedy” of the commons was the supposed willingness of freeriders to exploit commons for personal gain, but as discussed communal norms did a good job of preventing this. The “tragedy of the commons”, then, has very little to do with enclosures, which was a real, historical process that drove thousands of peasants from their homes to die while benefiting the rich. Enclosure was the action of private landowners to usurp communal property and drive others from it, erasing their historically recognized rights. Destroying the commons, not freeloading on it. All they have in common is greed.

Good correction to my choice of term. Too bad peasant revolts don’t happen every election year! Community-respected rules were moderated by the Church, on behalf of the manors … all that meek will inherit the Earth stuff. As a predatory species, this kind of thing is to be expected.

Of course you are right. But equity does include an additional right to appoint the directors (provided that other creditors are not justifiably concerned about the value of their claims). So I guess the right to appoint directors is probably the root of this idea that its the shareholders company. I’m always struck by the absurdly generous gift that limited liability represents to corporations. One would think with great privileges would come some sort of responsibility – particularly to those who might suffer from an abuse of that privilege – i.e. credits both secured and unsecured (like say employees). And sure enough there are provisions in most corporate law to reflect how damaging false trading can be. Just that I don’t remember anyone being prosecuted for it.

One might also observe that the idea behind this absurd gift was the facilitation of commerce in a risky environment – the Triangular trade etc. However I do question whether the privileges big corporations are able to finagle are now a brake on free commerce. Absurd asymmetries of information in things like insurance markets (how can anyone understand how these health polices work without a massive investments of time?) or blocking class action lawsuits enabling corporations to rip off their customers providing it is for small dollars.

There comes a point where the extraction of rents is actually a serious impediment to commerce. Not that anyone seems to care.

Ding DIng.

Yep, the equity owners get to make the rules because they elect the leadership. So by design equity owners have a stranglehold on their residual entitlement to the company’s largess, over the employees and the business units up until the point they run the corporation into the ground (bankruptcy), at which point the shareholders are left with nothing.

Middle management in corporations has the sole task of transmitting the will of shareholder elected leadership with the minimum negative impact on business units and employees. It a bit of a mess in execution as you can imagine.

It doesn’t appear to be a very fun game to play from where I sit…

There’s a difference between what you read in a book and what happens in the real world. In practice it’s the CEO who selects the board. For a board member to get less than 80% approval from shareholders is almost unheard of. Look at the clowns who run Wells Fargo.

That is simply not true in a pubic company setting and even not in a private company setting if you have sufficiently diffused ownership (or a controlling block and everyone else is hostage to what those owners do). A minority shareholding in a private company is a very vulnerable position in which to be.

I have no idea where you get these ideas from but if you really believe this sort of thing, you are a ready mark.

No, equity does not involve the right to appoint directors. The slate of directors is chosen by management, not by shareholders. Terms of board members are staggered to make them very difficult to replace even if dissidents work together to reject the directors nominated by management.

Boards have been fabulously cronyistic at many large companies like Oracle and Apple.

What does the corporation owe the state in exchange for incorporation? Because the limited liability of shareholders IS a government grant worth something. It is my understanding that when a company goes bankrupt, the creditors usually can’t sue the equity holders to get the rest of the money that they are owed. In exchange for allowing this “heads I win” (and get dividends) “tails you lose” (no suing shareholders) corporate structure, it isn’t unreasonable for the government to demand something other than “maximizing shareholder value” from corporations.

Yes.

If the government works for the people rather than the shareholders.

That is a neat point. Thanks.

Huh? I don’t understand the point you are trying to make.

The equity holders get wiped out. They lose 100% of their investment.

The creditors have claims on what value is left in the company. Equity holders have none.

If equity holders are found to have taken money out of the company (via dividends, buying assets from insiders, unwarranted bonuses), they can be sued by the creditors for fraudulent conveyance.

Moreover, in the UK and Australia, if you are a director of a company that is “trading insolvent,” as in operating when it cannot in fact pay its creditors (which includes suppliers, employees, and the tax man), you are liable PERSONALLY.

yes, the equity holders usually have their investment wiped out in bankruptcy. But that is rarely enough to make the creditors whole. And it is my understanding that the fraudulent conveyance cases are rare. So it is rare for investors to lose MORE than they have invested, even when the company has been operating on fumes, hope and credit for some time. By the time they declare bankruptcy, most companies have a negative net worth. That is WHY creditors are usually not made whole in a bankruptcy. But once their equity goes to zero, equity holders have not further personal responsibility to make the creditors whole. Absent a fraudulent conveyance finding, owners of equity aren’t PERSONALLY responsible for the debts that THEIR company has taken on. And that limit on ultimate liability is worth something to investors.

This self-sustaining system, however, faced challenges due to social upheaval after the Black Death, and the increased financial burdens placed on merchants and towns in order to fund warfare in France. When prosperity returned in the Tudor period a more ruthless form of capitalism took root, whose legacy remains with us today.

Really? Before the Black Death the villains were forbidden from traveling, and were considered the property of the Lords of the Manor, and conscripted at will.

After the Back death they were able to travel freely, and actually be paid for their work.

The situation for the majority of people under the rule described above was brutal. Kind and gentle it was not, Thanks to the demolition of the Saxon system after Willy the Conk took. control.

This was the period of King John and Robin Hood.

I suggest re-reading “A History of the English Speaking Peoples”

not an expert on English history I went looking for Willy the Conk search came up with mostly Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory – not being English it took me a while to figure out that Willie the Conk is a nickname for the Norman “conq “ueror William – 1066 and all that.

William the Bastard then rebranded as William the Conqueror.

He was a Norman, North man, a Viking.

Reading a bit between the lines, it seems the authors restrict medieval “capitalism” to what happened in towns like Cambridge. The rural lords and villeins were presumably still on “feudalism” – with obligations mostly in kind and service, not money.

A modern capitalist would find some different term to describe medieval Cambridge. Religious commune?

I find it disturbingly ahistorical to refer to this system as capitalism, a term which did not enter the language till the 19th century (capital in reference to money dating from the early 18th and capitalist from the late 18th century). It’s also a bit misleading to refer to ownership of property in the earlier time. This system was a part of feudalism while that still existed, burgage tenure (holding from a lord, as the authors note, or by subinfeudation, holding from someone who held from someone else) being one of the recognized varieties described by Pollock and Maitland in The History of English Law (before Edward I). The legal picture would have been complicated because, according to Wikipedia, Cambridge was a charter borough from some time in the reign of Henry I. That gave the borough, as represented by its burgesses, both rights and responsibilities in direct relationship to the Crown. From what I remember of Maitland, in the early days the question of who actually was answerable for the responsibilities was a bit obscure; the law was evolving, but what was clear was that rights and responsibilities went together. The notion of a cutthroat capitalist out for himself alone was probably literally unthinkable.

I’m not so sure about the compassionate label either, though. Charitable giving probably needs more analysis, as some of it was probably a sort of spiritual insurance and some may actually have had a business component crudely comparable to modern charitable annuities. But milking information from those medieval records is no mean task, and I’m interested in what has been produced.

The focus of this study appears to be on towns. The situation for townsfolk in the medieval period was often very different from the peasantry who were subject to the whims of their lords and had little or no real rights. In legal and social terms the quality of life and freedom of townspeople not subject to a feudal overlord was very different from the typical peasant. Feudal lords reluctantly accepted this situation because of the key economic importance of towns.

Sometimes you had a hierarchy of ‘freedoms’. In Medieval Dublin, for example, you had the main town, where the guilds dominated and people had relative freedom, but quite high taxes (mostly to pay for the city wall), you had the ‘Irishtown’, which was a sort of favela outside the town, where non English speaking workers had to sleep the night (they could work in the town and be free of a feudal lord, but were not allowed within the walls after nightfall), and church lands outside the town, which sometimes were under feudal law, but with the Church occupying the role of Lord, and sometimes were what we’d now describe as free trade zones (then called ‘liberties’), which was an area where the citizens were ‘free’ of a feudal lord and town taxes, but had to take their chances when the wild Irish attacked, as being non tax payers they had no right to protection within the walls and couldn’t call on the Lord to come fight for them.

But in general, in terms of freedom, being in a city was generally best in medieval times. But you couldn’t just walk in and settle, it was very tightly regulated.

The distinction between country and city in medieval Europe is a fascinating subject!

Italy had an earlier urban economic expansion than northern Europe, and, not surprisingly, Italians were pioneers of modern banking. Lombard Street, in London, and the Lombard Rate, in Germany, are two manifestations today of this medieval situation where northern Europeans relied heavily on Italians for financial expertise.

Although a bit dated, the work of Roberto Lopez, Raymond De Roover, and Carlo Cipolla are still wonderful introductions to medieval economic history.

“The city air will make you free“

Depends on when in the medieval period we’re talking about. Early medieval peasants had a relative lack of restrictions on them. Yes, they were still subject to the crown and had to follow what the crown said, and they were at risk of all sorts of invading armies. But in daily life they had a decent amount of freedom. Land ownership was common, there were systems for self-determination in communities. Not much in the way of regulation on what they could do with their land. Taxes, if they existed, came in the form of work service or raw goods. They were rarely conscripted, as military service was seen as a nobleman’s calling. It wasn’t until the 10th and 11th century that you got what Chris Wickham called “The Caging of the Peasantry,” when the nobility gained more independence from the throne and start subjecting the peasants to manorialism.

I thought of Robin Hood too and looked up Nottingham on a map. It’s not too far from Cambridge.

I bet those rich dudes had, like, hundred baggers from their properties and gave back a lot, but if I got a 100 bagger — say from 3 or 4 well choosen stocks — and had, by that point, several hundred million dollars, I’d be tempted to give some back — to political lobbyists and get my name on a hospital or museum.

It makes you wonder. Also, I wonder about whether equities are all that dodgy. Sure, the execs can pay whatever dividends they want and there’s not much you can do — BUT and this is a huge BUTT! You won’t give them money in the first place if you think they’ll screw you. They have to compete for capital (most of the time anyway, when the central banks aren’t mass manufacturing it). They can’t just screw you with impunity or they won’t get capital from anybody and they’ll have no fun at all. They can’t just do anything they want. One can’t lose grasp of the whole phenomenon when scrutinizing the individual parts.

I bet the landlords had to give to the churchs and hospitals or they’d be overrun with Robin Hoods. If you get a 50 bagger it’s still not bad. There’s a lot of elements to this ensemble. If you pick them apart and look at them separately you lose apprehension of the ghost in the machine.

Also (and time ran out before I could edit) if you look at Monty Python on Youtube it doesn’t look all that great back then. I saw one where a group of dudes in chain mail and metal helmets who seemed to be gaurds or soldiers didn’t even have horses to ride and had to walk banging something that looked like coconuts together to make horse hoof sounds and they skipped along pretending they were riding horses. It may be they werent from Cambridge but it makes you wonder. They also had one with peasants in a field whose faces and clothes were caked in mud. Even John Cleese himself didn’t look all that posh. You;d have expected some of the other Monty PYthon dudes not to get rich but if John Cleese can’t make it in medieval England it must have been hard times. Always thinking outside the box!

A suit of armor cost one years wages for ordinary people.

As the English demonstrated at Agincourt, a mounted Knight in Armor was an easy arget for a peasant with a knife – cut the girth, and the Knight hits the ground, and cannot stand back up – bit like a beetle stuck on its back.

Armor was high end fashions for men, to impress the ladies in the jousting tournaments.

Skills which were of little use after the black death killed off too many Villeins, and work became paid.

To change to an historical parallel – the change in value of Labor will be the situation our 0.1% will experience in the mass deaths caused by climate change. Good luck with your massive farm equipment, robots, tennis, polo and 100 ft yachts at that point in time.

N America was populated by Nomads. and Eurasia both Nomadic and farmed, for a reason.

I guess that was part of the point. Even the guys with armor had to skip along on invisible horses and make the huffbeat sounds themselves. If you’re Robin Hood it’s probably not even worth leaving the woods.

Cormac McCarthy forsaw all this is his 2006 novel THE ROAD which happened after compassionate capitalism failed in a final conflagration. It was just like Monthy Python, the the roaming gangs had makeshift armor and no horses, they had to skip around to get anywhere.

Synoia wrote: As the English demonstrated at Agincourt, a mounted Knight in Armor was an easy target for a peasant with a knife – cut the girth, and the Knight hits the ground, and cannot stand back up – bit like a beetle stuck on its back.

Just a niggle: as you may know but others don’t, it was the English longbow — which could drive an arrow through armor — that primarily put paid to the French knights and brought them down for the guys with the knives. The raised middle finger to display contempt supposedly originated as an English tradition because on the battlefield the English yeomen would hold up the fingers with which they drew their bows back to the French knights to demonstrate their opinion of and superiority over the French.

N America was populated by Nomads

Again, a niggle. N. America was far from exclusively populated by nomads. After Hernando DeSoto’s expedition crossed the Mississippi valley in 1541, they left accounts of running into built native townships every mile or so. Likewise, DeSoto’s men had a run-in with the inhabitants of a fortified native city in what would become Alabama,

One-hundred and fifty years later when the Duc De Cadillac traveled through the Mississipi all these townships were gone and the terrain had returned to nature. What had happened was that natives infected by the pathogens that the European colonists on the East Coast had brought and against which those natives had no defense, had fled their collapsing communities and carried those diseases further inland, wiping out the other native communities there ahead of the Europeans’ arrival.

It was the biggest bioweapons attack in history, if inadvertent. As much as 95 percent of the original human population may have been wiped out by the pathogens the Europeans brought.

Which this doesn’t contradict the overall point that you, Synoia, are making. The 0.1 percent will be unlikely to survive when the larger human population that supports their predations collapses.

May I humbly suggest that instead of having a museum or hospital named after you (as tempting as being treated in the “Craazyman Memorial Rickets Ward” does sound), that you instead invest in building a library dedicated to showcasing your achievements? It would be a great place to give 400,000-bagger speeches and could serve as a base of operations for your definitely-not-a-money-laundering-scheme foundation.

I agree that, on the surface, such a statement is so vague as to be meaningless. Perhaps this is meant as an allusion to the much later changes written about by Polanyi?

[meant as reply to Synoia]

It is not that capitalism comes in more and less predatory forms, it is that capitalism inevitably makes all forms more and more predatory over time (See Weber, ‘The Spirit of Capitalism’ on this) – with the exception of occasional unusual circumstances (e.g. mass mobilization warfare).

“Profit and community were reconciled in the Middle Ages in a way that we can learn from today.”

If, by ‘we’ you mean the odd enlightened individual, then yes, this is true we can learn. But if you mean ‘we’ as in society as a whole, then no we can’t learn from this, and we won’t. Society is not learning things right now, it is forgetting things. The above (excellent) post, it just one example among countless of the things forgotten. The question isn’t can we remember these things from the past again, the question is what is next to be forgotten.

I tend to agree with your bleak conclusion that society is forgetting rather than learning things right now, but I have a sense that there are many out there wanting to learn things that have been lost from current consciousness.

A pet idea is that the time is ripe for a little red book of 100 truths they don’t want you to know. Just don’t think I’m the right one to write it – it really needs a small collective.

If your “society as a whole” is the USA then I agree: it isn’t learning things now, hasn’t learned more or less as a whole since I suggest the New Deal. That a society can learn is possible if we understand societies as constructs with capacity for memory, long-term memory more specifically; and if we define learning as a change in long-term memory (not a controversial position for educational psychologists).

We can all agree probably that societies are chatacterized in part by distinct efforts to build and maintain a collective memory that should contribute substantially to the identity formation in individuals.

Why isn’t the USA learning? We’re not transfering material to the collective long-term memory. Seems like there should be counter arguments. I’ll take a stand and add that the transfer has been disabled by an imperial absolutist mentality of American exceptionalism.

It’s worse than that, an artificial memory is being constructed for us. “Who controls the past, controls the future/Who controls the present, controls the past”

Even the statues have to go. The Taliban definitely gets it.

Worse still, all those “who’s” just think they have control.

The systems they manipulate were designed by our ego mostly in denial of our id: “control” in this context is squaring or cubing the scope for unintended consequences.

Isn’t destruction or alteration of memories one of key steps in brainwashing?

Is Nicki Minaj the resurrection of medieval Cambridge’s public-spiritedness?

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2017/may/07/nicki-minaj-twitter-college-tuition-student-loans-contest

It is refreshing – rarely have I seen evidence that top pop stars or athletes are able to reflect socially and politically about their status, and suggest responses that I want to support. Minaj seems to be going farther than Springsteen even. Or has Springsteen been active behind the scenes?

Minaj should make her support available without meritocratic nonsense.

Check out Chance the Rapper, too. He just gave, iirc, over a million to the Chicago School District.

Medieval economics is more relevant than most people think. The only academic economist in Ireland who correctly predicted the nature and extent of the property bust in detail (and was widely hated by the banking industry for this) was Morgan Kelly, a specialist in the topic of medieval urban economics. I believe he was later quoted as saying he knew he was right when he heard some of his ex students on the radio reassuring everyone that the banks were secure and there were no problems at all with high property prices.

Thank you.

I have just found a 66 minute youtube video from Dr. Doom going by the name of ” Whatever happened to Ireland ? ” from October 2016 which I will now watch.

A friend of mine from the Republic also predicted the housing crash, but he is a sculptor & was only called a bollix.

People who predict major events only become famous after the event, and is a form of “I told you so.”

What is not discussed is how to pick these people from among the noise before the event.

Correlation is not Causation, nor is hind site a useful form of prophecy.

He never said ” I told you so “, to those who heaped derision on him for selling his semi-detached in Galway for a high price around 6 months before it all blew up & then renting a small place until the prices dropped enough so he could buy almost outright his dream house on the Mayo coast – he just grinned at them.

A great poker player…perhaps that had something to do with it.

Yes, it’s impossible to “interpret the market” in the Middle Ages (and the early modern period) without recognising the various forms of mutual obligation that tied people together.

And it’s even more important to keep in mind the question of the materiality of money itself in this period. There was a chronic shortage of coins throughout these centuries and a great deal of economic activity took place via elaborate credit networks, not through the direct purchase of goods and services with physical money. This led to the formation of a huge and in many ways quite problematic credit economy after about 1500. Economic historian Craig Muldrew has written about this in The Economy of Obligation (1998):

One of the things that I like to point out to people about the middle ages, is that it was a world without small change. While there WERE coins smaller than a penny, they were not that common. And was in a world where a skilled laborers wage was no more than a few pennies a day, Picture a world where there was no bill smaller than $100. You can’t buy a reasonably buy lunch. Cash was for big purchases or settling of accounts, not something that most people walked around with to make daily purchases.

This piece is very interesting but lacks context. Why do you think there was a peasant rebellion in 1381 (not the only one)? Rural people were being dispossesed of their lands (especially communally shared resources crucial to the quality of life (enclosure)). Then you might have to go to war in France and die of disease. Nothing kind and gentle about it.

I may have to invest in better tinfoil. I wear some heavy-duty stuff, one might even say it’s of mythic proportions. But NC once again reads my mind.

Been thinking about the Middle Ages a lot lately. Specifically, the Grail legends and their theme of resolving the dilemma of how to lead an authentic life in a fundamentally corrupt society. It’s said that the invention of marriage for love vs arranged marriages was a crucial development.

But it’s time to go to work. Thanks for the food for thought.

We can certainly gain, from reflecting on the higher regard for the common weal often shown by landlords and merchants in many medieval towns. Yet, then, as now, much of this philanthropy was very targeted in the direction of institutions that were of particular benefit to their benefactors.

Wealthy families often preferred to bestow large marriage dowries on only one daughter, so as to improve their chances of a marriage that furthered the family’s social climbing ambitions. Lavish convents were therefore heavily funded to allow wealthy unmarried women to live comfortable, even pampered lives within the cloister. Colleges and monasteries, likewise, were places where wealthy townsmen could prepare in comfort for legal or Church careers, while the eldest brother gained control over the family business or estates.

Just as the Koch brothers, today, can’t buy much more than a very thin veneer of virtue, through giving lots of money to the Met, or MIT– neither should too much credit be given to the wealthy philanthropic merchants, and landlords, of Jolly Olde Cambridge.

The various ideas about what and whom a corporation should be serving are obviously quite fluid. So the focus should be precisely on HOW can we make these ideas less fluid and, incidentally, make corporations work for the common good?

Some ideas: How about actually taking seriously the idea that corporate charters can be yanked? Why shouldn’t the public have a direct vote on whether a given corporation should be allowed to continue to exist? Why shouldn’t we collectively, for instance, be able to vote Facebook, Apple and Google into the cornfield and seize their assets for the public good?

Also, how about tax laws that give huge breaks to corporations that A) have at least 51% labor representation on their boards and B) have no more than a 2-to-1 ratio between the highest- and lowest-paid and compensated employees as reckoned on an hourly basis?

There’s a start.

Excellent, reasonable questions!!!

The answer, sadly, is far too simple. Right now Facebook, Apple, and Google can call on the resources of a heavily militarized police state, to crush any movement filled with reasonable people, like Pelham or Ulysses, if it starts to get traction.

We won’t start to see things get better– until we do more attempting to actually seize power, and less writing of sternly-written letters to the editor.

Pretty much agreed. Although I question the value of the heavily militarized police state. It is indeed fearsome, but only up to a point.

Yes! In a nation of over 300 million people, once people stop squabbling and unite to face down the storm troopers the people’s ultimate victory is assured. Our main challenge now is to ask our friends and neighbors: “If not us, who? If not now, when?”

Haven’t read the whole piece yet (gotta run to Dr’s appt.) , but with Yves’ comments re the exaltation of shareholder value, I found Karen Ho’s analysis of how it came about in her book Liquidated insightful.

Thanks for this well written and informative post, intro and body, as well as the comments. Just to add two cents: one shouldn’t ignore the role of the church in providing the social glue that held all this together. Not only were you required to believe but those outside the church could receive quite draconian treatment. The church anointed kings and provided a belief system that supported the legitimacy of their power. They also still gave lipservice to the notion that ostentatious wealth was bad and the ascetic Christ-like life was good. After a lifetime of rape and pillage knights were often required to become monks on their deathbeds in order to receive absolution.

To boot you had to contribute to the church and actually tithe under penalty of law. Recall that at that time the state and the church were very intertwined. Care for the poor was done by the church, as was for the sick. Recall Bedlam was originally the Bethlehem Hospital in London. England was not unique in this in that the Church and the state were intertwined all over western Europe.

It sounds like a real estate boom. Older landed families developed various plots of land which they owned but the King had to give them some kind of charter to do so? The proto model for modern taxation. And these property markets prospered because half the profits from the rents were given back to the community in the form of charity to hospitals and churches. So half the money from real estate, or maybe something like 13th C. finance-insurance-real estate, was invested back into the community. Half. That’s a lot of money going into 13C. health-education-welfare. No wonder it was so successful. Interestingly this property “market” fell apart after the Black Death killed off half the population. So it took at least half the population to produce an economy rich enough to pour money back into the social commonwealth. Half must be the magic formula. It is what is required of corporations to actually maintain their own viability.

Thus you assert “It sounds like a real estate boom” is correct.

Where do you think the concept of “fee ownership” came from? The Normans ruling England. Fee ownership is how land is owned in the US, among others, today.

The US Constitution with its “no standing army” and “right to bare arms” derives directly from the feudal lords duties’ to the crown.

William could not pay his knights, after the battle of Hastings, so he gave them landholdings with a “fee” attached.

“Fee” was money, loyalty to the crown, a duty to keep the peace, and a duty to raise a regiment when demanded.

The system in Europe was different. I believe the Crown owned everything, which result in major kissing of the Sovereign’s ass, and the asses of players at Court, to keep what one has.

very interesting, synoia… we haven’t changed much

The harsh and un-relenting existence before Capitalism:

https://libcom.org/files/timeworkandindustrialcapitalism.pdf

“This general irregularity must be placed within the irregular cycle of the working week (and indeed of the working year) which provoked so much lament from moralists and mercantilists in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

A rhyme printed in 1639 gives us a satirical version:

You know that Munday is Sundayes brother;

Tuesday is such another;

Wednesday you must go to Church and pray;

Thursday is half-holiday;

On Friday it is too late to begin to spin;

The Saturday is half-holiday agen.

John Houghton, in 1681, gives us the indignant version:

When the framework knitters or makers of silk stockings had a great price for their work, they have been observed seldom to work on Mondays and Tuesdays but to spend most of their time at the ale-house or nine-pins . . .

The weavers, ’tis common with them to be drunk on Monday, have their head-ache on Tuesday, and their tools out of order on Wednesday. As for the shoemakers, they’ll rather be hanged than not remember St. Crispin on Monday . . . and it commonly holds as long as they have a penny of money or pennyworth of credit.”

It all sounds rather pleasant.

When workers owned the means of production they behaved very like students today and left it all to the last minute, spending the rest of their time drinking, it’s what people do when left to their own devices.

I think medieval philanthropy at Oxford warrants a mention. At Magdalen College we continued an annual alms-for-the-poor tradition. After the chapel service on Maundy Thursday, red hot coins would be thrown from a high public pulpit outside the chapel to a waiting crowd of local poor, not only to help the poor, but also for the amusement of seeing the red hot coins fought over, picked up, dropped in pain, picked up. (By the 1960s, the occasion had of course become a fun event where less than red-hot pennies were scattered for the schoolboy choir to compete for.)