By Sandwichman. Originally published at Angry Bear

Is there a neo-classical theory of immiseration?

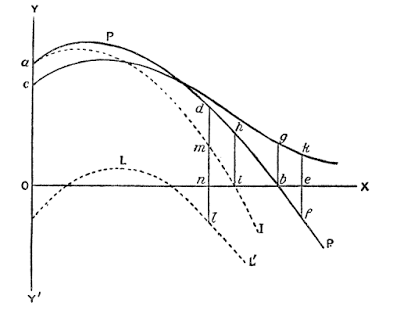

Below is the marvelous Chapman hours of labor diagram (follow the link for a more detailed explanation). It looks complicated but it really only contains four curves representing, roughly, long-term and short-term productivity, income and fatigue. But there is more to it than Chapman realized or that I have previously noticed.

The context for this diagram is William Stanley Jevons’s discussion of work effort in his Theory of Political Economy:

A few hours’ work per day may be considered agreeable rather than otherwise; but so soon as the overflowing energy of the body is drained off, it becomes irksome to remain at work. As exhaustion approaches, continued effort becomes more and more intolerable.

The “L” curve in Chapman’s diagram echoes the lower curve in Jevons’s figure VIII, presented to illustrate the “painfulness of labour in proportion to produce”:

In this diagram the height of points above the line ox denotes pleasure, and depth below it pain. At the moment of commencing labour it is usually more irksome than when the mind and body are well bent to the work. Thus, at first, the pain is measured by oa. At b there is neither pain nor pleasure. Between b and c an excess of pleasure is represented as due to the exertion itself. But after c the energy begins to be rapidly exhausted, and the resulting pain is shown by the downward tendency of the line cd.

Chapman was primarily concerned with the length of the day optimal for output, which would be measured on the X axis of his diagram by the distance Ob. The optimal working day from the workers’ perspective, however, would be On and would terminate at the point where the marginal income from another time unit of work would just equal the marginal pain of working.

But the intervals from n to i and from i to b add another dimension to the diagram that has been overlooked. From n to i the worker gives up proportionally more in work effort than he or she receives in extra income. Finally, during the interval from i to b, workers endure additional pain in exchange for a decrease in total income. Beyond b, the incomes of both workers and employers are reduced.

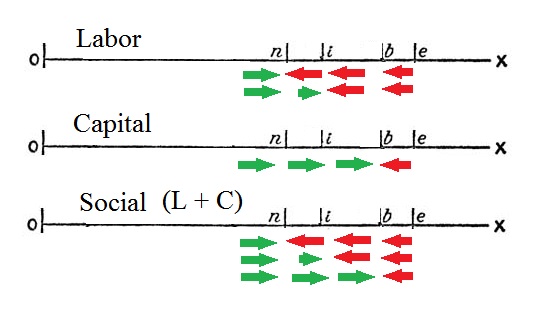

The four phases of working time can be labeled cooperation, exploitation, immiseration and ruin. The incentive for employers is to progress inexorably toward the last phase unless regulated by legislation or collective bargaining. The following animation illustrates the contrast between the workers’ gains (green) and losses from lengthening of the working day and the employers’ gains (blue) and loses.

The conflict between labor and capital over the length of the working day can also be illustrated less kinetically by the following close-up of the X axis from Chapman’s diagram. The green arrows indicate income gains, the red arrows income losses or pain cost:

The bottom line, showing the social aggregate, indicates that the income gain for capital at the optimal point b for output is essentially a transfer of income from labor, which also has to invest additional work effort to accomplish that transfer. Up to the output optimum point there is a small net surplus of income that is, however, dwarfed by the quantity of work effort pain cost required to generate it. This does not even qualify for the Kaldor-Hicks compensation criteria. From capital’s perspective, however, the small net return and larger transfer appears to be all simply gain from expanded output — growth is good! (Just don’t look under the hood).

Chapman gave no indication of being aware of the immiseration implications of his analysis. John Hicks gave even clearer indication that he was not aware of the immiseration implications of Chapman’s analysis. Hicks observed that “it had never entered the heads of most employers that it was at all conceivable that hours could be shortened and output maintained” but asserted that trade unions “will not usually need to exert any considerable pressure in order to bring about a reduction” in circumstances where the working day exceeded the output optimum. As if workers should be content to be ground down into wretched poverty provided they didn’t drag their employer down with them! The output optimum is not a good place on the X axis for workers to be.

Only the Marxist economist, Maurice Dobb, appears to have noticed the importance of the relationship between wages and “the worker’s expenditure of energy and his ‘wear and tear.’”

What was implied in the economists’ retort to the advocates of the so-called Work-Fund leads to the apparent paradox that the more the workers allow themselves to be exploited, the more their aggregate earnings will increase (at least in the long run), even if the result is for the earnings of the propertied class to increase still faster. And on this base is erected a doctrine of social harmony between the classes. But it does not follow that the workers will prefer to be exploited to a maximum degree, or that attempts to limit this exploitation are based on fallacious reasoning.

There is no scale on the Chapman diagram and this turns out to be a useful feature. Different occupations, technologies, individuals and wage levels generate a variety of scales. One could conceive of aggregating these scales either in an overall average or clustered in quintile or decile groups. The latter procedure would be valuable in exploring whether a substantial number of workers were being pushed into conditions of immiseration even though the overall average was still safely in the exploitation range.

It is worth remarking that based on the relative length of the segments in Chapman’s diagram, the optimal length of the day for workers would be less that 72 percent of the optimal output day. For example, if the optimal length of the workweek for output was 48 hours, the optimal week for workers would be 34.4 hours. Of course Chapman’s diagram is not based on empirical measurement but Chapman had investigated in depth the extensive statistical and experimental data available at the time he was formulating his theory, so, while his proportions cannot be assumed to be precise they probably represent an informed impression — a ballpark estimate — of general relationships.

In conclusion, yes, there is a neo-classical immiseration theory. The economists who propounded it apparently were unaware that it was such a theory. By extension, that immiseration theory is a crisis theory. There is no built-in mechanism of negative feedback from prices that militates against the passage from the immiseration phase to the ruin phase. Hicks assumed that a “very moderate degree of rationality on the part of employers will thus lead them to reduce hours to the output optimum as soon as Trade Unionism has to be reckoned with at all seriously [emphasis added].” But by the time exploitation has progressed to the immiseration phase, trade unionism doesn’t have to be “reckoned with at all seriously” by employers. The trade unions would already have been defeated somewhere between point n and point b on the Chapman diagram’s X axis.

Good lord this is depressing..

For most of human history, labor was dominated by a much more relaxed approach to work:

While some bemoan automation of repetitive tedious work routines, the other side of that coin is that if profits were not concentrated in the hands of the uber-wealthy, automation could result instead in a 4-6 hour working day at a living salary.

“if profits were not concentrated in the hands of the uber-wealthy”, if only.

‘Trade Unionism has to be reckoned with seriously.”

As the bankruptcy of Alitalia demonstrates, inconveniencing customers with labor-management conflicts is an excellent way to end immiseration for good. Or at least, replace it with a different kind of immiseration.

Yes, life for both laborers and businesses is fragile at “b“

I’m having a hard time understanding the income line. Why does it curve down instead of up over time? I would have thought that it would be a straight line with a slope of whatever the hourly wage rate is. This sentence makes no sense to me whatsoever:

I’ve worked some bad jobs in my day, but never any with a negative wage rate after a set number of hours…there must be something about the Y-axis I’m not understanding. What’s it measured in? $, utils, or what?

When the trouble of keeping the job exceeds the pay. Having to get daycare in order to work the expanded hours would be one kind-of-benign example. Or finding transit home after a super-late (or before a super-early) shift. (I’m intentionally leaving out the kind of jobs, e.g. artisanal gold mining, that can literally kill people.)

Can happen.

Awww…ok. I wasn’t thinking holistically enough. Thanks for the clarification (and reality check).

I’ll add increased medical bills from stress-related injuries (both physical and psychological) as another “cost of doing business” for laborers.

…like, “I could work another 10 hours this week, but the extra pay wouldn’t be enough to cover the bills from my chiropractor and the divorce lawyer.“

I think this is very important. Really thinking it through would lead to going beyond attention to more immediate physical and psychological wear and tear to considering distortions in the family, social life, and the broader culture as well. E.g., if you’re being run ragged in your gig jobs you’re probably going to be that much more primed for immediate gratification, less inclined to consider problems that are difficult to think about, etc.etc. etc.

I’m usually leery of graphing social-psychologically complex phenomena but this article, which looks to be an excellent example of internal critique, is great.

I once had a temp proofreading job working for two sadistic lesbians who were both younger than me. That was bad. Every temp job I had, just about, was a cesspool of stupidity. Although in some cases when there was nothing to do you could read something, like a book or a magazine. But you had to sit in one place while you did. Nothing in the Temp world even approaches the stupidity and craven kowtowing I observe at my current employer, where I work in a relatively senior & allegedly learned capacity.

I think I got fired by the lesbians after 2 days when I missed where a comma should have been. I’ve seen people get fired for doing too good a job. Nobody reading this will find that shocking, since we don’t expect anything better from working life by and large.

In fact, I’ve only had 1 good job ever. That was my first job out of college, right out of college and I worked there 2.5 years. Oh and one more. I was a good paperboy and enjoyed delivering newspapers — I started with The Washington Star, an afternoon paper long gone that actually made a name for itself covering the Civil War. Then I delivered the Washington Post in the mornings. Being a paperboy was agreeable because it lasted about 45 minutes and you were done. But you had to do it seven days a week. Sometimes my Mom did it to give me a break. Or a neighborhood kid would step in and do it. You had substitute paperboys you could rely on, mostly kids from school. One of them, a sub, also had a WaPo route a few neighborhoods away and we’d sub for each other. He was the smartest kid in the school and, frankly, the smartest human being I’ve ever met in my life. Even to this day. But I was better than him at geometry, that was the one subject where I actually helped him with homework. hahahah, The shlt you remember. I always remembered learning geometry and it seemed like a miracle from the mind of God.

It would be good for many jobs to have reinforcements. But then somebody in charge would have to know what they were doing & care. Those are two factors missing from most jobs and then the jobs basically suck within the first 15 minutes. Time isn’t really the only basis vector for this phenomenon. if every job allowed for the cultivation of perception and administration of creativity in an ordered and satisfying way, there would be no time to worry about time. You’d be too busy. LOL

I had the afternoon paper route when I was in middle school. 25 papers, took 15-20 minutes to deliver by bike, I made about $10/week – mostly tips because I had the routine down. But the only reliable sub I ever had was the kid who had the morning route. And he had 200 papers and had to get up at 5am to get them all delivered, and yes I had to sub for him. He made way more than I did but there is no way I would have ever switched positions with him. So even in the same industry, there would be different labor onerous-ness curves, in my case mostly dependent on when you had to go to work!

Weird coda – here I am while he was the one general killed in Afghanistan. It turned out in the military he specialized in logistics, which made perfect sense to me.

I was also an after school paperboy as a youth. Seems like something I don’t see around anymore, though…do they still exist?

Me too. That was a fantastic opportunity for kids, and it no longer exists as far as I can tell. People who subscribe to a print paper (I’m one of the holdouts) are far fewer now, and therefore spread farther apart, even in a relatively dense suburban neighborhood like mine. Not like the old days where a kid on foot could deliver to 100 people as I did. The papers are now delivered by adults a car or van, probably covering a vast territory in order to make a pitiful amount of money.

There is a free weekly paper here that gets delivered to every house whether they want it or not, and they advertised a program to get neighborhood kids delivering on those routes. But I’ve never seen a kid doing it.

Until I dropped my NYT subscription on the 9th of November last year, my paper in Brooklyn had been delivered in the morning by a very nice 45 year old from the Bronx who threw thousands of papers for both the WSJ and NYT every morning before 7:00AM.

Like previous commenters in the thread I did that job, up to about 200 papers in the morning, when I was a kid in the 70s and it was a great introduction to the commercial world, from time/planning constraints to collecting from everyone on the route once a month.

Like my subsequent job at Burger King, these jobs are now professions for people in their 30s and 40s around here and everything that was good about them as a kid is an insult as an adult. Labor needs lots more dignity today than its afforded.

I once had a teaching job working for 2 evil heterosexual men who opened an international school in Shanghai with money made from arms sales by their father. I think I got fired by the 2 heterosexuals when I mentioned that word on the street is they are mafia. Did I mention that they were heterosexuals? Good.

I think the implication was the two ladies were man haters. Makes the story funny enough. Relax.

Oh, excuse me, thanks for the clarification. Because a joke is ALWAYS funnier when mansplained. I did not know lesbian was code for man-hater, but duly noted I can now relax. Because you told me to.

Enough with the PC Police act.

A more niche acceptable version of the statement would have been, “two sadistic bank managers?”

Acting like a jerk and being called out for it isn’t gendered unless you have an inferiority complex about being female. But you decided to telegraph that too.

Craazyman is regularly politically incorrect. He calls women “hot” on a regular basis too. I assume that would also offend you.

Yves, you should take some happy pills. You are one nasty person….

The problem with drawing diagrams to represent nominal data is that the resulting curves are mis-interpreted as functional relationships between whatever is represented on the verticle axis with whatever is represented on the horizontal axis. It looks like math, but it’s only a picture. There is no continuous and differentiable function that relates time, labor and misery to profits and income, or to any combination of them. These concepts are not measurable properties of the real world like mass or velocity. They are purely psychological constructs that cannot be quantized and turned into mathematical expressions.

True enough. It needs to be clearly kept in mind that this is a conceptual diagram and not a graph of data. The fact that it is not math does not, however, diminish its value as a scientific tool. A Venn diagram or a classification matrix is also “not math.”

I have admittedly played around with the diagram by “measuring” the length of the x-axis segments. My intention in doing so is not to assert that the optimum day for the worker is 72% of the output optimum day but to provoke reflection on what the actual proportions might be.

Using myself as an example, I used to work in a grocery store with a concrete floor. After four days of work my feet would be so sore that could hardly walk. It would take three days to recover to the point where I could hobble through another four days of work.

I insisted on working a three-day week (I had seniority, we were unionized) and my feet both didn’t get so worn out and didn’t take as long to recover. My optimum week was three days. At four days I was still capable of producing additional output. A five day week would have entailed frequent absenteeism and probably shirking at work.

I don’t mean to be harsh, but Venn diagrams for example couldn’t be more Math, which is not just numbers, functions, and equations. Set theory is quite literally at the heart of Math, as it is used to prove properties of numbers, e.g. Dedekind’s definition of the real numbers.

As an illustration of economic theory, this is great but at the same time quite unsatisfying. It shows clearly the curse of much economic theory – oversimplification. It may have been a bit more accurate in Dickensian times, but a realistic model of modern work practices would have to try to account for the effects on pain and productivity of breaks in the working day, for coffee or lunch. A more sophisticated model might also address the after lunch slump in productivity, and the differences between Monday, Wednesday and Friday productivity.

I’m easy, Moi. If you say a Venn diagram is math, fine, it’s math. Then the diagram is also math. Contra what dutch claims, the concepts ARE measurable properties after all. We just don’t have yardsticks to measure them with. The lack is in our instruments, not in the things we can’t measure.

While I agree that more modern work practices and types of employment would affect the shape of the curve, that wouldn’t make the elements more measurable, so the gain in precision of specification would be sort of a Pyrrhic victory. Personally, I would like to add in environmental wear and tear. But again, the diagram is already “too complicated” for the purposes of mainstream economic analysis, which would prefer not to consider such “externalities” except as an afterthought.

“..the concepts ARE measurable properties after all. We just don’ t have yardsticks to measure them with. The lack is in our instruments, not in the things we can’t measure them with.”

If you have no means to measure them, then they are not measureable.

I don’t know about that…And what I mean is that you are very confident about what can be and cannot be measured with a yardstick. What I measure with my yardstick is my own creation which does not include what my own creation has excluded. Let me illustrate. There is a pop index which is called the US unemployment rate. This index measures US unemployment, but it measures it under the boundaries of its own economic-reality-made-policies’ construction .This is why the labor force participation rate has become so popular in the last few years. (We can go to the Department of Labor website and will find tons of data and different indexes related to unemployment and its measurement). But of course, and going back to the labor force participation rate, the economy has changed and is changing in ways such, -which would take me too long to describe here- that the labor participation rate is every time more and more inadequate to measure unemployment .

What you are referring to is the precision of a measurement. Some measurements are less precise than others. But if the precision is so bad that you can’t tell whether what you measured is there or not, you’ve reached the point where it’s time to say that there is nothing there.

No. IMO you are framing this incorrectly. By introducing the term precision your last recourse will be to show me the standard meter kept in Paris. However, the standard meter kept in Paris won’t help us with all we are dealing with here. I.e , to measure unemployment is primordially the task of counting units, unemployment units (if I can say that). But, what is an unemployment unit?. What is to be counted must be defined. We all can say that country X and the US have unemployment rates, yet what an “unemployed unit” is will differ among them. We could indeed, combine many sources and tools to complete a good picture of US unemployment (tax returns, net jobs added, population,etc), yet the extend of what is an unemployment unit to be counted is based on politic-philosophical criteria and on what a particular economy constructs. By the way, this chat reminds me of Ron Levi and John Hagan’s work on the politics of counting dead bodies to classify or not classify as such the Darfur genocide.

Georgescu-Roegen wrote about dialectical concepts in which there is an ambiguous “penumbra” between states. He contrasted that with “arithmomorphism” that sought to reduce everything to what could be tractable mathematically. There are at least two problems with the latter. One is the fabrication of pseudo-mathematical pseudo-science and the other is the neglect of issues that can’t be tidily reduced to measurement.

I am sympathetic to dutch’s criticisms to the extent they are warnings against constructing a pseudo-math dogma from a conceptual diagram. But I don’t buy the other dogma that unless something can be “measured” — at least unambiguously if not precisely — it doesn’t have the status of “science.” There are things that are measured precisely but are revealed as meaningless tautologies once one understands the context in which the unequivocal “yardsticks” were established (“IQ” for example).

Labor was once mostly physical, and after a certain point the human body would be unable to work further. For today’s “knowledge workers” the limiting factor is attention and mental energy which can be difficult for observers to evaluate. It is possible for workers to be “working” for hours and hours in a way that is satisfactory to managers without actually producing anything.

Which brings back memories of one of my lousy jobs. Mandatory face time in the office, even though I could have gotten a laptop and done my work in the mountains or at the beach.

And the office? What a toxic cesspool of negative people. Yeesh.

Then there were the time thieves. They realized (correctly) that their jobs didn’t require 40 hours of work each week, so they busied themselves with other things. One lady wrote a book. A guy started a computer consulting business. And two of the top dogs became consultants.

Good times, good times.

Ah that explains yesterday.

Great article! Really hope to see more on this subject, takes the wind out of the ‘be happy to have a job at all’ family of arguments.

I wonder if someone could explain for me though: what changes for the worker at point i? (Going from exploitation to immiseration) The article says at this point additional work leads to less total income, which doesn’t jive with hourly or salaried pay. The previous phase change (cooperation/exploration) seems to be where marginal worker _utility_ per additional unit of work goes negative. Perhaps I’m misunderstanding.

Good question. The background for this is the realization that “hourly wages” are determined as an aliquot part or a daily or weekly wage in which the hourly fluctuations of productivity will have been evened out. Thus a $15 an hour wage for a 40-hour a week job can be alternatively conceived of as a $600 a week wage divided into 40 parts. Divide that $600 into 50 parts and the hourly wage would be $12 an hour.

Overtime premiums are easily defeated by recalculating the regular rate downward while assuming a “usual” amount of overtime.

So even once the worker passes point n (where marginal utility goes negative, and he doesn’t really benefit from working longer hours) his total earnings are continuing to increase, (though his hourly wage may decrease) because his productivity increases and some portion of that gets passed back to the worker. At point i, the total earnings go flat and start to decrease.

Sorry to ask to be spoonfed, but how does the employer continue to profit between i and b without needing to pass some of the gains back to the worker?

Is it, as Mel suggests above, that external costs due to long hours begin to mount? (Daycare overtime, premade meals, health complications, etc) This certainly is the case, but I wasn’t sure if it was being taken into account on the charts.

I don’t think that was in the original intention of the diagram but that doesn’t mean it isn’t relevant, as would be the issue of commute time as well as cost.

What the diagram is showing is a composite of a hypothetical series of discrete work arrangements that collectively have continuously varying wage rates and lengths of working day. My example above about the 40-hour a week job at $15 an hour and the 50-hour a week job at $12 an hour thus refers to two distinct work arrangements and doesn’t imply a transition of a given job from one arrangement to the other.

The employer is operating in two markets with different competitive characteristics — selling output in the product market and buying labor in the labor “market.” Profit arises from the different characteristics of those markets.

In this case, the additional profit between i and b is an assumption of the neo-classical model — the assumption that the employer continues to buy additional units of labor up to the point where marginal revenue product = zero.

I have to admit that I have been familiar with the Chapman diagram for nearly 20 years and have written about it in several published articles and only now noticed the significance of the interval between i and b. Chapman himself appears to have not noticed it. Please excuse if my explanations are a bit ad hoc, I am having to think through the implications as questions such as yours arise.

If I understand the explanation correctly, then curve I is not just income, but (income minus value of leisure). Curve P is marginal product, and in classical theory that it the same as income.

Point i is the point where you can still get useful results if you work an extra hour (and you will get paid for those results), but the money is worth less to you than that same hour would be worth for leisure.

Point n, earlier on the time line, takes into account that long days are unpleasant in themselves, also by making your tired next days less pleasat overall.

Point b is where you can still push extra results out of an extra hour, but only at the cost of productivity loss on the next days. Short term gains that cannot be sustained indefinitely.

In many jobs, there will also come a point where you literally destroy output by working more on the day itself, through mistakes etc. But that aspect is not on the chart, afaict.

Good catch! Chapman:

So it is not, as I wrote that income becomes negative past i but that the value of income falls below the value of leisure sacrificed. I will amend the EconoSpeak and AngryBear versions.

This is why we need universal health care. It is so mathematically dumb to do it our way, as it’s obvious the cost of health care is fixed to the population size, not to the number of people that have jobs, so if you had it you wouldn’t need pointless 40hr or more weeks anymore since you can hire two people to, say work 22.5 hrs each over the week. I just gave you, the employer, 5 more hours every week executed with reasonably fresh hands. Given that spouses are today part of the work force, a family could still stay middle classish.

But I finally know why the employers are so “stupid” about this, they b*tch about health care costs but they really, really like the control it gives them. “Sure, go ahead, quit. How you gonna pay for little Johnny’s kidney?”

I flew spirit once. Never again. The cattle car nature of the seating and lack of leg room led me to

conclude that at some point the low price doesn’t matter.

I can’t help but think that one of the solutions of future work shortages due to automation will be reductions in labor hours, which will help better redistribute the available work to other workers who would otherwise not have a job.

“If you’ve got a lot of work, the socially correct thing to do is share some of it with others, instead of burning yourself out.”

Unfortunately, as present events are suggesting, the answer chosen to this problem is greater outlays for police suppression of the grievances of the semi-working classes. So, as is the case with past changes in the composition of the labour “market,” new occupations arise to take up the slack. This is eerily similar to the rise of the “Pinkertons” a century ago as managements tools to suppress the labour union “menace.”

The UK has a long hours culture with low productivity.

Germany and France have a short working week with high productivity.

The longest working hours are often found in Asia, e.g. Japan and Korea both have very low productivity.

Successful economies can have low productivity and unsuccessful ones, high productivity, e,g. France.