Yves here. I don’t pretend to have a good answer to this problem because there is not good answer, ex say engaging in a WWII level effort to combat climate change as well as relocate big portions of at-risk communities to higher ground. But this would take much more in the way of political will than anyone seems to have. And that’s before you get to the fact that the 40 or so year war on government has reduced the competence of and faith in many institutions.

But notice here a predictable element: New Jersey’s flood relief and prevention efforts are directed disproportionately to the rich, who in most cases have more ability to relocate than low-income households.

This story also provides a in-depth window on the scale of the problem. And even those whose homes that probably won’t be flooded are exposed. For instance, I’m in a part of Manhattan that is on relatively high ground. But what happens to New York City, as seems likely sometime in the next 20 years, when Manahttan floods up to 14th Street?

By John Upton, who writes about coastal change, climate policy, and bioenergy at Climate Central. Follow him on Twitter: @johnupton. Originally published at Climate Central; cross posted from Grist

Coastal communities are enduring growing flood risks from rising seas, with places like Atlantic City, sandwiched between a bay and the ocean, facing some of the greatest threats. Guided by new research by Climate Central’s Scott Kulp and Benjamin Strauss, reporter John Upton and photographer Ted Blanco chronicled the plight of this city’s residents as they struggle to deal with the impacts. Upton spent months investigating how the city is adapting, revealing vast inequity between the rich and the poor.

A driver plowed a sedan forcefully up Arizona Avenue, which had flooded to knee height during a winter storm as high tide approached. The wake from the passing Honda buffeted low brick fences lining the tidy homes of working-class residents of this failing casino city, pushing floodwaters into Eileen DeDomenicis’s living room.

“It wasn’t bad when we first moved in here — the flooding wasn’t bad,” DeDomenicis said on a stormy morning in March, after helping her husband put furniture on blocks. She counted down until the tide would start to ebb, using a yardstick to measure the height of floodwaters climbing her patio stairs. She was tracking how many more inches it would take to inundate the ground floor. “When somebody comes by in a car, it splashes up. It hits the door.”

DeDomenicis has lived in this house since 1982, a few hundred feet from a bay. She used to work as a restaurant server; now she’s a school crossing guard. Her husband walked a mile to his job at Bally’s Casino until he retired in January. They’ve seen floods worsen as the seas have risen, as the land beneath them has sunk, and as local infrastructure has rotted away. “It comes in the front door, the back door, and then from the bottom of the house, in through the sides,” DeDomenicis said. “You watch it come in and it meets in the middle of the house — and there’s nothing you can do.”

Two miles east of Arizona Avenue, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is spending tens of millions of dollars building a seawall to reduce storm surge and flooding risks for Atlantic City’s downtown and its towering casinos, five of which have closed in the past four years. A few miles in the other direction, it’s preparing to spend tens of millions more on sand dunes to protect million-dollar oceanfront homes.

But the federal government has done little to protect the residents of Arizona Avenue, or the millions of other working class and poor Americans who live near bays up and down the East Coast, from a worsening flooding crisis. Seas are rising as pollution from fossil fuel burning, forest losses, and farming fuels global warming, melting ice, and expanding ocean water. With municipal budgets stretched thin, lower-income neighborhoods built on low-lying land are enduring some of the worst impacts.

Climate Central scientists analyzed hundreds of coastal American cities and, in 90 of them, projected rapid escalation in the number of roads and homes facing routine inundation. The flooding can destroy vehicles, damage homes, block roads and freeways, hamper emergency operations, foster disease spread by mosquitoes, and cause profound inconveniences for coastal communities.

Atlantic City is among those facing the greatest risks, yet much of the high-value property that the Army Corps is working to protect was built on a higher elevation and faces less frequent flooding than neighborhoods occupied by working class and unemployed residents — an increasing number of whom are living in poverty.

Earthen mounds called bulkheads built along Atlantic City’s shores to block floods have washed away, or were never built in the first place. Flap valves in aging storm drains have stopped working, allowing water to flow backward from the bay into the street when tides are high. At high tide, stormwater pools in Arizona Avenue, unable to drain to the bay. The flooding is getting worse because seas have been rising along the mid-Atlantic coast faster than in most other regions, and the land here is sinking because of groundwater pumping and natural processes. High tides in Atlantic City reach more than a foot higher than they did a century ago, and sea-level rise is accelerating.

New Jersey has done little to address the problem, aside from administering federal grants that have helped a limited number of residents abandon or elevate vulnerable houses. “We expect each town to focus on planning and budgeting for mitigating flooding,” said New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection spokesperson Bob Considine. Atlantic City can nary afford the kinds of capital improvements needed to provide meaningful relief.

The Army Corps last year began a study of bay flooding in a sweeping stretch of New Jersey covering Atlantic City and 88 other municipalities, home to an estimated 700,000. The study was authorized by Congress in 1987, but it wasn’t kickstarted until federal research identified widespread risks following Superstorm Sandy.

The bay flooding study is “fairly early in the process,” said Joseph Forcina, a senior Army Corps official who is overseeing more than $4 billion worth of post-Sandy recovery work by the agency, including construction of a $34 million seawall in downtown Atlantic City and tens of millions of dollars worth of sand dune construction and replenishment nearby. The study is expected to take more than two years. “We really are in the data-gathering mode.”

The study will help the agency propose a plan, which Congress could consider funding, to ease flood risks when high tides and storms push seawater from bays into streets and homes. It will consider the effects of sea-level rise, but it won’t directly address flooding from poor drainage of rainwater, meaning any fixes spurred by the study are likely to be partial at best. “The Corps is not the agency that deals with interior drainage,” Forcina said. “That’s a local responsibility.”

Floods are driving up insurance rates, while routinely causing property damage and inconveniences. Federal flood insurance promotes coastal living in high-risk areas, and the program is more than $20 billion in arrears following Hurricane Katrina and Sandy. Arizona Avenue residents received Federal Emergency Management Agency letters in March warning of insurance rate increases ahead of 5 to 18 percent a year, which “makes us want to leave even more,” said Tom Gitto.

Raising three children on Arizona Avenue, Gitto and his wife have been unemployed since the closure last year of Trump Taj Mahal, where they worked. He said the flooding has become unbearable but property prices are so low that they feel trapped. Two houses on Arizona Avenue recently sold for less than $35,000. Gitto paid a similar price for his fixer-upper in the 1990s, then spent more than the purchase price on renovations. Flood insurance provided $36,000 for another refurbishment after Sandy ravaged their home.

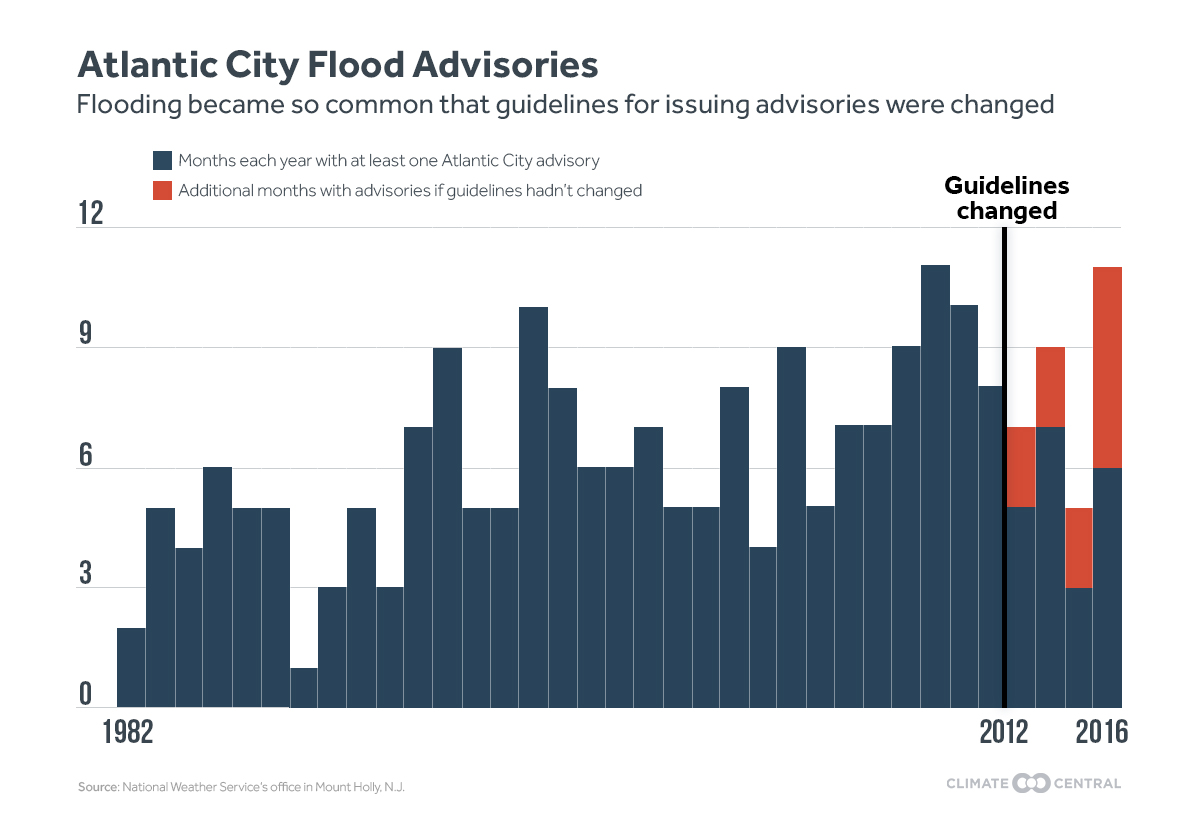

Flooding strikes the Jersey Shore so often now that the National Weather Service’s office in Mount Holly, New Jersey, raised the threshold at which it issues flood advisories by more than three inches in 2012 “to avoid creating warning fatigue,” flooding program manager Dean Iovino said. Such advisories were being issued nearly every month in Atlantic City before the policy change, up from an average of four months a year in the 1980s.

One out of 10 of the 20,000 homes in Atlantic City are at elevations that put them at risk of flooding each year on average, Climate Central found, though some are protected by bulkheads and other infrastructure that help keep floods at bay. The research was published Wednesday in the journal Climatic Change.

The proportion of the city’s streets and homes affected by flooding is projected to quickly rise. Within about 30 years — the typical life of a mortgage — one out of three homes in Atlantic City could be inundated in a typical year. That would be the case even if aggressive efforts to slow climate change are put in place, such as a rapid global switch from fossil fuels to clean energy.

The worsening woes aren’t confined to Atlantic City, though risks here are among the greatest in America. Neighborhoods near bays can experience rapid increases in the number of streets and homes exposed to regular floods, with small additional sea level capable of reaching far into flat cityscapes and suburbs.

Elsewhere at the Jersey Shore, in Ocean City, New Jersey, the analysis showed one out of five homes are built on land expected to flood in typical years, a figure that could rise to nearly half by 2050. Other cities facing rapid increases in risks include San Mateo along San Francisco Bay in Silicon Valley, the lumber town of Aberdeen at Grays Harbor in Washington state, and Poquoson, Virginia, which has a population of 12,000 and juts into the Chesapeake Bay.

The greenhouse gas pollution that’s already been pumped into the atmosphere makes it too late to prevent coastal flooding from getting worse. It’s simply a matter of how much worse.

The benefits of acting now to slow the effects of warming later would become clearest in the second half of this century. In Atlantic City, if global pollution trends continue and defenses are not improved, 80 percent of current homes risk being inundated in typical years by the end of the century, the analysis showed. By contrast, if greenhouse gas pollution is aggressively reduced almost immediately, the number of homes expected to be exposed to that risk in 2100 would fall to 60 percent.

As efforts to protect the climate flounder in the U.S. and elsewhere, unleashing higher temperatures and seas, communities like the DeDomenicises’ have three basic options for adapting. They can defend against floods with infrastructure that keeps tidal waters at bay, such as bulkheads, pumps, and marsh and dune restorations. They can accommodate the water using measures such as elevating existing houses and building new ones on stilts. And they can relocate altogether, an option that’s expected to lead to mass migrations inland during the decades ahead.

Modeling by University of Georgia demographer Mathew Hauer projects 250,000 being forced by rising seas from New Jersey by century’s end if pollution levels remain high, with nearly 1.5 million refugees fleeing to Texas from U.S. coasts elsewhere. And from Florida — the poster child for sea-level dangers in the U.S. — 2.5 million may be driven to other states.

All three strategies are being pursued to some extent in Atlantic City. All of them are expensive, limiting the options available for a city in decline. “Cities boom and bust,” said Benjamin Strauss, coauthor of the new study and vice president for sea level and climate impacts at Climate Central, which researches and reports on climate change. “Neighborhoods can thrive, and fall into decay. Those are, to some extent, natural cycles of economic life. But now, superimposed onto that for Atlantic City at just the wrong time is this awful existential sea-level threat.”

Barrier islands like Absecon Island, upon which Atlantic City grew as a gaming and vacation mecca, line the East Coast, from New York to Florida, natural features associated with the coastline’s wide continental shelf and shallow waters. Until barrier islands were developed and armored with seawalls, roads, and building foundations, low-lying shores facing the mainland could keep up with rising seas. Wind and waves washed sand and mud over growing marshes, helping to build up the land. Now, a century of development has locked down the shape and position of the islands, blocking natural processes.

“It’s a huge problem for the U.S.,” said Benjamin Horton, a professor at Rutgers University in New Jersey, which is a global leader in researching sea rise. “These barrier islands are important for so many things — important for housing, important for the economy. They’re important for a variety of industries. They’re especially important for ecosystems. And the barriers protect the mainland from hurricanes; they’re a first line of defense. You lose the barrier islands and where do you think the big waves are going to hit?”

As barrier islands and mainland coastlines were developed, wealthy neighborhoods clustered near ocean shores, where the elevations tend to be higher — which reduces flood risks — and where views are considered the best. Lower-income neighborhoods and industrial zones grew over former marshlands near bays and rivers, where swampy smells are strongest and where flooding occurs most frequently.

That divide between rich and poor is clearly on display on Absecon Island, where stately houses built on higher land facing the ocean are often occupied only during summer — when risks of storms are lowest. The vacation homes and downtown Atlantic City casinos will be protected from storm surges by a new seawall and sand dunes built by the Army Corps, despite lawsuits filed by homeowners angry that dunes will block ocean views.

Poorer neighborhoods are exemplified by Arizona Avenue, a block-long street between a bay and a minor thoroughfare. Bricks in fences and walls are stained by floodwaters and decaying beneath the effects of wakes from passing cars. The century-old, two-story houses have concrete patios and little landscaping — plants are hard to grow in the flood-prone conditions.

During high tides that accompany new and full moons, the street can flood on sunny days. Rubber trash cans can be buoyant in floodwaters, tip over and foul the street with spoiled food and bathroom waste, which residents sweep away after floods recede. Cars are frequently destroyed. Many of the houses along Arizona Avenue had to be stripped and renovated after Sandy filled them with floodwaters and coated walls and ceilings with mold.

The winter storm that inundated Arizona Avenue in March was a typical one for the region. The nor’easter struck during a full moon, meaning it coincided with some of the highest tides of the month. Floodwaters stopped rising a few inches beneath the DeDomenicises’ front door. Emergency crews patrolled in vehicles built to withstand high water. These kinds of floods are called “nuisance floods” by experts.

Nuisance floods are becoming routine features of coastal living around America, and their impacts are difficult to assess. Washington and other major cities could experience an average of one flood caused by tides and storm surges every three days within 30 years, according to a study published by researchers with the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists in the journal PLOS One in February. Rain and snow that fall during storms increase flood risks.

Residents of Arizona Avenue describe anxiety when tides and storms bring floods, especially if they aren’t home to help protect their possessions. The rising floodwaters can be emotional triggers — reminders of the upheaving effects of floods wrought by major storms like Sandy in late 2012 and Winter Storm Jonas in early 2016. Some of the residents have spent months living in hotels while their homes were repaired following storms. One of Tom Gitto’s children was born while the family was living in a hotel room paid for by the federal government after Sandy.

Susan Clayton, a psychology and environmental studies professor who researches psychological responses to climate change at the College of Wooster, a liberal arts college in Ohio, said such triggers can lead to sleeping difficulties, “profound anxiety” and other symptoms. The frequent risk of flooding may also make people constantly fear for their homes and for the security their homes provide.

“It tends to be very important to everybody that they have some place that they feel they can relax, where they can be in control,” Clayton said. “Your home is your castle. When your home is threatened, that can really undermine a sense of stability and security. It’s not just the flooding, it’s the idea that it’s your home itself that’s being threatened.”

The economic impacts of nuisance floods can also be far-reaching — researchers say they’re more impactful than most government officials assume. “Since they don’t get a lot of attention, we don’t have a data record of nuisance flooding costs,” said Amir AghaKouchak, a University of California, Irvine, scientist who studies hydrology and climatology.

AghaKouchak led a study published in the journal Earth’s Future in February that attempted to quantify the economic impacts in large coastal cities. The researchers were hamstrung by the dearth of data. Their preliminary findings, however, suggested that the cumulative economic impacts of nuisance floods might already exceed those of occasional disaster floods in some areas.

“There’s a lot of cost associated with this minor event,” AghaKouchak said. “Cities and counties have to send out people with trucks, pumps and so forth, they have to close down streets, build temporary berms.”

On Arizona Avenue, residents say they feel abandoned by all levels of government. Like an Appalachian coal town, many here depend upon a single industry — an entertainment sector that’s in decline, anchored by casinos that draw visitors to hotels, arcades, restaurants, gas stations and strip clubs.

“They forget about us,” said Christopher Macaluso, a 30-year-old poker dealer who owns a house on Arizona Avenue and grew up nearby. “We’re the city. If they didn’t have the dealers, the dishwashers, the valet guys, the cooks and the housemaids, what have you got? We definitely feel left out.”

With casinos operating in nearby Pennsylvania and elsewhere following the lifting of gambling bans, the flow of visitors to Atlantic City has slowed over a decade from a gush to a trickle. Some towering casino buildings stand abandoned, like empty storefronts in a dying downtown. Others are filled well below capacity with gamers and vacationers; their gaudy interiors faded and gloomy.

One out of every six jobs in Atlantic City was lost between 2010 and 2016 as nearly 5 percent of the population left, according to the latest regional economic report by New Jersey’s Stockton University, which is building a campus in the city. The number of Atlantic City residents using food stamps rose to 15 percent in 2015, and more than one out of every five children here is now officially living in poverty.

President Trump’s construction of two ill-fated casinos in a saturated industry intensified the Atlantic City gaming bubble that began its spectacular burst a decade ago. (As president, Trump is dismantling regulations designed to slow sea rise and other effects of warming.) The city is so broke that its government operations are being overseen by New Jersey.

“From the moment they started pulling handles in Pennsylvania, the cash that was pouring into slot machines in Atlantic City started to fall,” said Stockton University’s Oliver Cooke, who compares the city’s economic plight to that of Detroit. “As the economy melted down and the land valuations in the city headed south, the tax base just completely melted away.”

Unable to pay for far-reaching measures taken by wealthier waterfront regions, like road-raising in Miami Beach and sweeping marsh restorations in the San Francisco Bay Area, Atlantic City has taken only modest steps to ease flooding.

Using funds from a bond sale and state and federal grants, the city has been refurbishing sluice gates in a canal that were built to control floodwaters but haven’t worked in more than half a century. It plans to replace flap valves in two stormwater drains near Arizona Avenue for $16,000 apiece. “We’re treating that money like gold,” said Elizabeth Terenik, who was Atlantic City’s planning director until last month, when she left its shrinking workforce for a job with a flood-prone township nearby.

That’s far shy of the tens of millions of dollars being spent just blocks away. The Army Corps is using Sandy recovery money to alleviate hazards in wealthier parts of the city and elsewhere on Absecon Island and in New York and other nearby states, while flooding affecting low-income residents of Arizona Avenue and similar neighborhoods is overlooked.

“The Corps does not say, ‘Here’s a problem, and we’re going to fix it’ — somebody has to ask them to help,” said Gerald Galloway, a University of Maryland engineering professor and former Army Corps official. “It depends on a very solid citizen push to get it done. The Corps of Engineers has a backlog of construction awaiting money. You need very strong organizations competing for it.”

Coastal New Jersey’s working class have little power in Washington and their cities manage modest budgets. The divide in Atlantic City reflects a grand injustice of global warming — one that’s familiar to Pacific nations facing obliteration from rising seas, and to Alaskan tribes settled by the government on shrinking coasts. While the wealthy may be able to adapt to the effects of climate change, the poor oftentimes cannot.

“In some cases, the most vulnerable populations will not be able to move,” said Miyuki Hino, a Stanford PhD candidate who has studied coastal resettlements around the world. “In other cases, they’ll be forced to.”

I was born, raised and have lived at the Jersey Shore my entire life (64 yrs). Coastal flooding has been part of the lifestyle for as long as I can remember. It didn’t get as much attention when I was young because the population dwindled to us “clamdiggers” between Labor Day and Memorial Day. Today many of the summer population has moved here permanently for a variety of reasons. Many of the houses were built when codes were lax and because they were only to be summer bungalows. Of course everyone wanted to be on the barrier islands close to the beach and boardwalk. Builders “made” land by bulkheading lagoons, canals and streams, dredging the bottom soft muck and backfilled to the bulkhead height. The resulting land was always subject to compression and sinking as the fill was mostly decomposed organic material… Building on pilings wasn’t common until the late 90’s early 2000’s.

Atlantic City is a study in boom town mismanagement. It had an east coast monopoly on gambling and the money flowed and the money fill the states coffers.. The promised improvements “off boardwalk” were never made.. it was always a ghetto a block or two away from the casino’s.. Then came competition in other states… and it’s too late for AC….

I’ve been an avid boater for most of my life, a surfer in my younger years.. I live on a river directly connected to the ocean. I lived through Sandy. I do not observe any sea rise.. I do not take my boat into the bays anymore because they are still shallow since Sandy.. The benchmarks I use are the seawalls and jettys which have marked high water since I was a kid. At low tide my part of the river is still a mudflat.

You would think if the sea were rising it would be noticeable at low as well as high water.

I’d be interested to hear how much of the flooding described in the article is attributed to land sinking vs sea rising… As my experience would point to the former a primary culprit.

The barrier islands have always changed… it’s Mother natures way…. and when the Army Corps build their dunes she will take them away… just has she has taken the millions of dollars in sand they have already pissed-away on the beach replenishment projects they done…

http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/sealevel.html

Here in Ottawa and Montreal, it looks like this huge flooding is being treated as a one time event. Despite all the talk about rising water levels over the last 10-15 years due to the melting ice caps or climate change, it’s depressing to see the number of new houses in this flood zone.

This article is more proof of how we’ve lost all sense of priorities.

What we are living is not just Mother Nature changing her tune, it’s first and foremost cheapness and bad planning.

The truth is that we built and did not maintain. And instead of maintaining, we built even more.

https://www.google.ca/amp/www.cbc.ca/amp/1.4112073

Slightly OT, but indicates the difficulties that even people with more money and social capital encounter in dealing with (possibly) climate change caused flooding. The very wet spring has combined with changes in policies in controlling the lake levels in the Great Lakes to cause serious flooding and erosion for lakeside properties and facilities on Lake Ontario in NYS.

But it turns out that even homeowners who had been responsible citizen-consumers and taken out flood insurance are having their claims denied by their insurance companies, who are classifying this event as a surge, not a flood.

In a market, you’re either the market-maker or the mark.

NYS has responded by sending mobile units to assist flood victims with their insurance claims.

(Translation: having the state Department of Financial Services reason with/cajole the insurance companies).

> classifying this event as a surge, not a flood

As Orwell didn’t write, “Who controls the taxonomy controls the future….”

“In a market, you’re either the market-maker or the mark.”

Truer words were never said.

Man (doesn’t) plan and god laughs

“From the moment they started pulling handles in Pennsylvania, the cash that was pouring into slot machines in Atlantic City started to fall,” said Stockton University’s Oliver Cooke, who compares the city’s economic plight to that of Detroit.

When casino gambling began in NJ in 1976, there was a widespread, faith-based belief that NJ in the east and Nevada in the west would remain the nation’s two gambling meccas forevermore.

Unfortunately, there was no actual federal legislation to ensure such an outcome. It was just a good concept and a good story, so they ran with it. Due diligence? Bah, we’re a sovereign state. It’s for da boids.

Incredibly, though we now know that state-licensed gambling is a kind of like Starbucks branches — keep adding ’em till the market is totally saturated — Andrew Cuomo in New York thought it would be a great idea to build some more mega-casinos in New York. They’re raking in $3 million a week … but it’s slated to fall as another giant one opens in the Catskills next year.

“Transactions of decline,” as Jane Jacobs would call them.

John Upton misses the serious problems with Measure AA, the regional tax measure that Bay Area voters approved in June 2016 to restore and protect the region’s wetlands. Those drawbacks were detailed in the San Francisco Bay Guardian’s recommendation to oppose the measure:

Regional measure

Prop. AA

Regional wetlands tax

NO

This measure ties an urgent cause, the restoration and protection of the San Francisco Bay’s wetlands, to a dangerous policy, a regional tax levied by appointed officials. It also starts to expand regional government in the Bay Area – before anyone has had a chance to discuss what that ought to look like.

Long before sea level rise was recognized as a threat, environmental groups were working to save The Bay’s shrinking tidal marshes. The wetlands cleanse and retain the Bay’s waters, help prevent flooding, and provide habitat for wild plants and creatures. Climate change has made their value even more apparent. To borrow the Sierra Club’s apt phrase, tidal marshes offer “a natural and growing levee” that slows storm surges and lowers the height of waves and encroaching waters.

And the Bay wetlands are in dire need of help. A regional approach makes sense; everyone in the nine Bay Area counties has a stake in the wetlands’ health. Measure AA would raise $500 million over 20 years for projects that reduce trash and pollution, restore wildlife habitat, improve water quality, and more.

But the measure has problems. While an annual $12 parcel tax seems like a small price to pay for ensuring the wetlands’ health, it’s unfair: Google and other corporations whose big new campuses are threatened by rising water would pay the same $12 as individual homeowners. A tax on the assessed value of property would be much more equitable.

And Measure AA has a much bigger problem.

The tax would be levied and administered by the San Francisco Bay Authority, a public agency created by the California Legislature. The Authority is governed by a five-member board of appointees who are chosen by yet another appointee, the president of the Association of Bay Area Governments, which is itself on the verge of a hostile takeover by an autocratic state agency, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission.

So who would decide how to spend the money? Nobody who was elected to that job. Whom do you complain to if you think the decisions are wrong? Good luck with that; SF’s current representative is Scott Wiener, and it’s entirely possible in the future that nobody ever elected by a San Francisco voter (and thus not accountable to any of us) will be doling out our tax dollars.

Measure AA also furthers the creeping privatization of government, stating that “[t]he Authority shall give priority to projects that,” among other things, “[m]eet the selection criteria” of the Coastal Conservancy, the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission, and San Francisco Bay Joint Venture.

San Francisco Bay Joint Venture is a public-private entity whose members include the Bay Planning Coalition, a private organization that last year backed MTC’s efforts to remove key anti-displacement policy from the forthcoming update of our region’s official land use and transportation blueprint, Plan Bay Area.

The measure’s supporters note that it would be the first regional tax in the Bay Area. If it passes, it would set an somewhat disturbing precedent at a time when local business and political elites are clamoring for the expansion of regional government– without any discussion of how that government should be run.

We’d gladly support an equitable proposal to restore and protect the Bay wetlands that mandated democratically accountable governance. We’d also gladly welcome a much larger discussion of how regional government should work – how much power it should have, and how the people who wield that power should be chosen.

Regional government may very well be part of the Bay Area’s future, and there are good arguments in favor of it (should someone be able to tell Cupertino not to approve a huge new Apple headquarters without providing any housing at all)? But it involves really complex issues of local land-use authority, local spending authority, and how the members of a regional agency are chosen.

We’re already worried about how the regional bodies, the Association of Bay Area Government and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, operate with little oversight (which means, in the end, in the interest of developers, not the public). Measure AA takes us a long way further down a path that we haven’t even begun to map.

Paying taxes for wetlands restoration is a fine idea. We can even live with the unfair parcel tax. But first let’s decide who ought to handle the money. Vote No on AA

What was allowed in the past in terms of development is somewhat forgivable because we lacked the technology available today. The real crime is that we still allow certain development to take place. Development where there is a high to moderate risk of flood shouldn’t be allowed.Probably even in a place of low risk of flooding because we don’t really know what will actually happen in the future. We could continue on the present destructive path or move to a less destructive one. One thing people seem to miss is how the development in a watershed changes the watershed. When you replace grass trees and other plants with asphalt or concrete you decrease the ability of a watershed to contain water. It ends up as runoff and the runoff happens at a faster rate hence more flooding. This is probably one of the major factors in the recent north east and Canadian flooding. If people don’t start to work with mother nature instead of against her she will destroy them.

IMO, a lot of unpopular decisions need to be made and since our leaders do not want to become lightning rods, they use the “free market” excuse to wash their hands.

Market Stalinism.

The lead that is buried.

The mania for coastal living in a country with lots of empty land is the real issue here. Barrier island development was highly controversial even before global warming was thought about. But in an earlier time there seemed to be a better understanding of the practicalities. Here in SC beaches would be lined with cheap frame houses on stilts, not the current McMansions by the water that imply permanence. Location, location seems to be the mantra and let someone else sort out the problems. Should we really weep if Florida, the swamp that turned into a real estate powerhouse, returns to its natural state?

“…..floods are becoming “routine” features of coastal living around America”

From the exception to the “routine” is essentially a risk assessment which unfortunately humans use and value the immediate past to make a judgment. Despite the fact that 10-20-50-100 years ago the information is available from ones own experience, relatives, friends and the guy down the street, no less data in public records to change dramatically the picture.

There are too many areas with extensive development all over the country and the world to change the outcome with insurance or public funds.

Paying off politicians to change the outcome and use of funds has been in place for thousands of years, But in a major war or large enough natural disaster even the rich cant be saved.

People took a risk and now “they” should pay the piper – what’s wrong with that?

One of the first persons I worked with when I joined an environmental engineering firm 40 years ago was the firm’s chief hydrologist.

His simple advice stays with me til this day: “Don’t live near the water.”

Besides underestimating the power of water, for starters, liquids don’t compress, people have no idea what’s mixed into flood waters: every cesspool and sewer, garbage, trash, you name it. Flood water is obscenely filthy.

It’s the Titanic.