Yves here. Among other things, derivatives contracts all elect governing law, which is either US or English. So that alone makes “What happens to English law contracts entered into by parties in EU jurisdictions post Brexit?” a non-trivial issue.

Mind you, one of the appeals of Cyprus before its banking crisis was as a way for foreign investors seeking to invest in Russia, and even Russians wanting to invest in Russia but wanting access to a more mature and cleaner legal regime, was to go through Cyprus and enter into English law contracts, which in the case of disputes would be adjudicated in courts in Cyprus set up to handle English law cases. So this isn’t as unprecedented, as the post mentions.

By Uuriintuya Batsaikhan, an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel who previously worked at UNDP in Mongolia and the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin, and Dirk Schoenmaker, a Senior Fellow at Bruegel and a Professor of Banking and Finance at Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University Rotterdam. Originally published at Bruegel

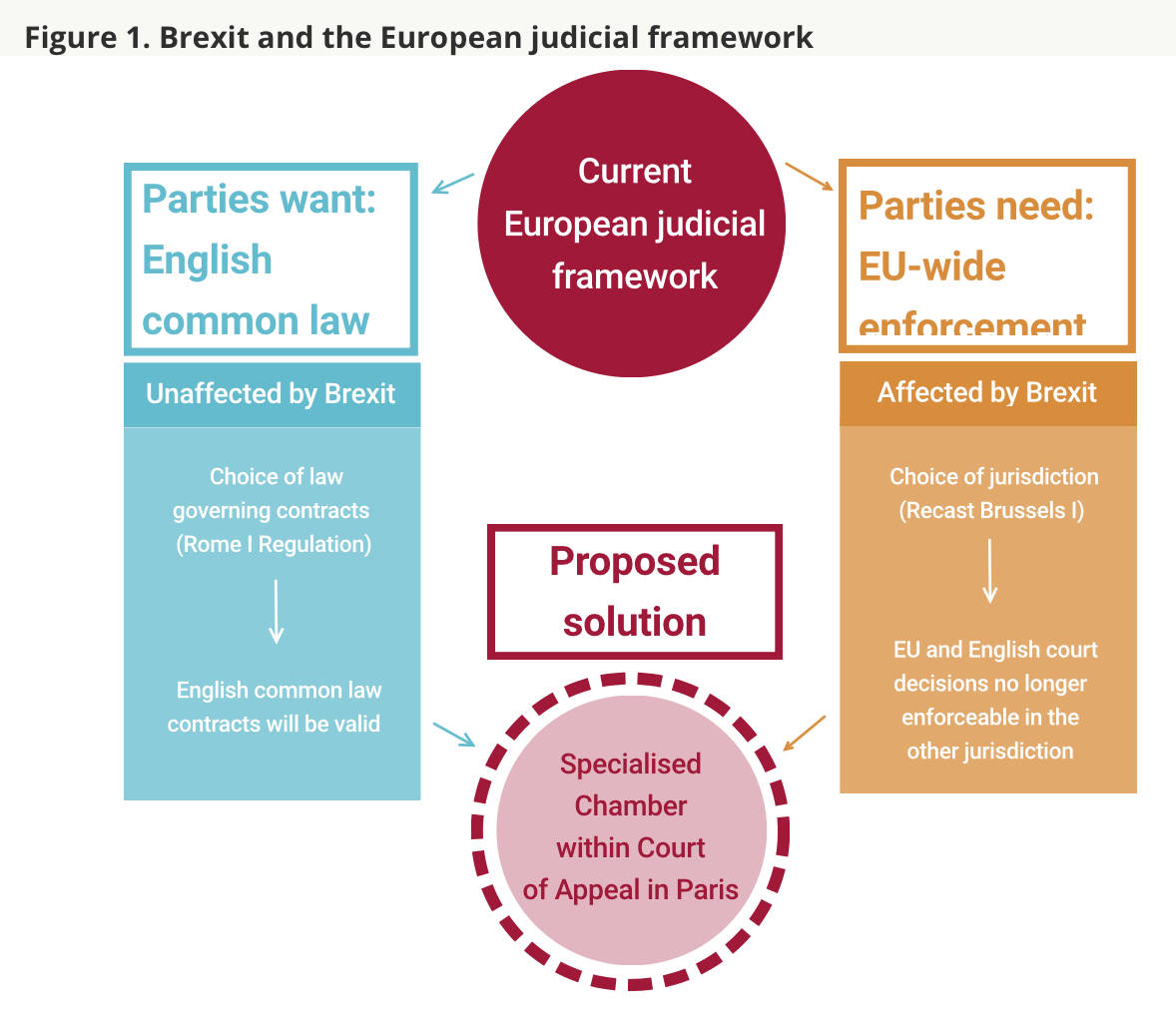

English common law is the choice of law for financial contracts, even for parties in EU members with civil law systems. This creates a lucrative legal sector in the UK, but Brexit could make UK court decisions difficult to enforce in the EU. Parties will be able to continue using English common law after Brexit, but how will these contracts be enforced? Some continental courts are preparing to make judicial decisions on common law cases in the English language.

The UK is home to the world’s largest over-the-counter (OTC) foreign exchange interest rate derivatives market, with 36.9% compared to the US share of 19.5%. The UK is also the second-largest market for OTC interest rate derivatives, with 39% second to the US share of 41%.[1] Naturally, surrounding this large financial sector there is a vibrant legal sector where financial contracts are drawn up, enforced and disputes are resolved.

English common law is the preferred choice of law in commercial and financial contracts. This reinforces London’s position as a global center for international dispute resolution. With Brexit, the UK’s position in the European Union’s legal landscape will change. However, these changes will not necessarily challenge the supremacy of English common law.

At the moment UK court rulings are enforceable across the EU. The EU has a common judicial area governed by a regulation known as Recast Brussels I or the Brussels Regime. This regulation sets out a common set of rules governing which courts have jurisdiction in civil and commercial matters in the EU. Recast Brussels I creates a common judicial area, ensuring mutual recognition of court decisions. Thus a decision in one member state is enforceable throughout the EU.

When the UK exits the EU, Recast Brussels I will no longer apply to the UK, and as such decisions made in UK courts will not be automatically executed in other EU member states. This means that additional arrangements will need to be made to achieve enforcement and recognition in individual EU member states of legal decisions made in UK courts. This is currently the case with regard to US judgements and their enforcement in EU member states.

The EU also has rules that let contractual parties choose the law under which they draw up contracts. In addition to Recast Brussels I, the EU is governed by a legal framework known as Rome I. This set of laws gives the parties the freedom to choose the law to govern their contractual obligations. In contrast to Recast Brussels I, participation in Rome I is not exclusively for EU members. That is, when the UK exits the EU, it will exit both the Recast Brussels I and Rome I regulations. But Rome I can be adopted back into UK domestic law by an Act of Parliament.[2]

This means that parties to a contract will have little difficulty choosing the law that will govern their contract – EU parties will still be able to draw up contracts under English common law if they wish to. However, if cases are settled in UK courts, it will no longer be certain that these decisions will be recognised and enforced in other EU countries. Access to a common judicial area could be limited, and negotiating a post-Brexit legal agreement on mutual recognition and enforcement of judgements between the UK and EU might prove to be a lengthy and uncertain process.

The parties could, in fact, choose to submit the case to (for example) a French Court, which falls inside Recast Brussels I. And if the UK reenacts Rome I, this will make it binding for the French court to admit the common law contract.[3] However, at the moment French courts would struggle to actually try the case because of a lack of common law expertise, which makes it highly unlikely that the parties would choose to do this.

Figure 1 summarises these judicial aspects of Brexit.

Figure 1. Brexit and the European judicial framework

It has to be noted that there are existing options outside the UK for parties who wish to seek arbitration on a contract drawn up under English common law. Presently, the standard choice of law in international arbitration of commercial and financial services contracts is English common law with English as the choice of language. This is the set-up of international arbitration courts outside the UK including the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), located in Paris; the Hong Kong International Arbitration Center (HKIAC); and the Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC

And there are already examples of the use of the English language in continental European courts. In France, Germany and the Netherlands the use of English is allowed in civil and commercial disputes, when all parties to the dispute consent to the use of English in conducting hearings, examining the evidence and appeal.

In the Netherlands, for instance, the Rotterdam District Courts allows use of English since January 2016 in cases involving maritime, transport law and international sales of goods. Use of English in the procedures entails that hearings are conducted in English, official records made in English, but the final decision is rendered in Dutch. But the use of English in a procedure does not change the application of Dutch procedural law. Going a step further, the Netherlands is setting up a specialised court, the Netherlands Commercial Court (NCC), to be opened in 2017/2018. The NCC will deal with large-scale international commercial disputes. The working language of the court will be English, but the court will apply Dutch law. The NCC aims to attract London and other international clientele by offering a cost-effective alternative to the City legal market.

In Germany, the District Courts of Aachen, Bonn and Cologne have started a pilot project where hearings can be conducted and documentary evidence can be presented in English without interpretation.[1] Use of English is allowed as long as both parties agree and the case involves civil cases exceeding 5000 euros and the case is of “international” nature. The pilot project gave way to a larger initiative that aims to establish chambers for international commercial matters at district court levels in Germany. The draft bill is currently being reviewed. If the bill is adopted, these specialised chambers will conduct hearings, file cases and even deliver judgments in international commercial cases in English. But they will still apply German law.

And in France, since 2010 the International Courtroom of the Paris Commercial Court has been accepting hearings and processing of case documents in English, German and Spanish, while the final decisions have to be delivered in French.

However, there is now a suggestion in France to go even further, using not just the English language but also English law. A recent report by the Legal High Committee for Financial markets of Paris put forward a proposal to create a specialised chamber within the Court of Appeal in Paris to deal with international trade and financial market disputes. This specialised chamber would deal with international business law litigation in English and be able to apply common law both in cases of first instance and appeal. In order to do so, the chamber would comprise of competent judges that are able to examine evidence, conduct hearings and deliberate in English, applying highly specialised technical elements pertaining to international commercial and financial contracts.

In this sense, the recent proposal suggesting a specialised chamber for international commercial dispute resolution under the Court of Appeal in Paris is a step forward into an uncharted territory, whereby English will be the working language in the French court while at the same time judges and the lawyers need to be able to apply common law within a French court system. The appeal procedure, accordingly, will also be administered through the French system.

The main difference between civil law courts and common law courts is not the language, but procedure. In the common law procedure, the case is conducted by the parties and the judge makes the decision, whereas in the civil law procedure the judge conducts the procedure and the parties comment on the case. Using common law in French Courts would require a decision regarding the extent to which judges interpret the law.

If Paris wishes to be an international center for commercial dispute litigation, France could to a large extent accommodate common law and the use of English, which is the standard language for international commercial and financial contracts. Indeed, currently established arbitral tribunals work in exactly this way (English language and common law procedures). However, for this overall project to be feasible, France would need to make large investments in legal and human resources.

We should also remember that Ireland and Cyprus exercise common law in their arbitration and have access to the European common judicial area. As with the financial sector, the legal services sector is subject to competition to attract clients. In this sense Paris is one center entering the fray in this competition. It remains to be seen if and where legal services eventually move.

But one thing we can say. President Juncker may have spoken too soon about the falling importance of English in Europe. On the contrary, legal professionals might soon need to reach out for the Oxford dictionary of Law.

[1] Kern, Christoph (2012) “English as a court language in continental courts”. Erasmus L. Rev., 5, 187.

We thank Simon Gleeson, partner at Clifford Chance for helpful comments.

[1] For detailed analysis see Batsaikhan, U., R. Kalcik and D. Schoenmaker (2017) ‘Brexit and the European financial system: mapping markets, players and jobs’, available at http://bruegel.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/PC-04-2017-finance-090217-final.pdf, last accessed 15 June, 2017.

[2] The Bar of England and Wales (2016) ‘The Brexit Papers”, available at http://www.barcouncil.org.uk/media/508513/the_brexit_papers.pdf, last accessed June 1, 2017.

[3] Legal High Committee for Financial Markets of Paris (2017) “Report on the Implications of Brexit”, available at http://ibfi.banque-france.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/banque_de_france/HCJP/Rapport_05_A.pdf, last accessed June 1, 2017

Could be an opportunity for Ireland to take over some of the prior roles of England.

And by an amazing coincidence just a few weeks ago Ireland started building a major new court complex for its Supreme Court (I walked past it this morning, first drilling rigs just in). If Irish lawyers get a whiff of this, there is going to be a gold rush for office space around it.

Similarly EU humanitarian legislation was written by British lawyers, which is ironic when you hear folks saying that leaving the EU means somehow the UK will be lose the protection of human rights laws.

I have to admit I found this article frustrating in that it creates a fruit salad of too many legal concepts, some of which are already well defined, while others, not so much, thus making it difficult to arrive at any clear conclusion.

First of all there is the issue of accepted language, which should not be an essential matter in deciding disputes. There may be a handful (at most) of cases where a case hinges on how a given term is translated, but I have yet to see one. And this is notwithstanding the fact that contracts generally give predominance to interpretation in one language.

Second there is the matter of which judicial channel will hear the case, mainly commercial or civil. In most European legal systems (I think this is homogenised, but I may be incorrect), there are separate procedural laws governing civil and commercial cases. European contracts thus specify from the get-go which courts should have competence to hear suits, thus already expressly making the contract subject to one set of courts, in one specific country.

Third, there is the issue of jurisdiction, which would be the most pertinent matter in such cases. Here, I deal with what is technically known as “a boatload” of commercial contracts, and they all uniformly specify jurisdiction in a specific clause. True, disputes often arise as to the validity of these clauses in international litigation, with some actors alleging, for instance, that under the commercial procedural law of the claimant’s country, the contract should first be deemed subject to its own jurisdiction to determine its validity before it can be sent elsewhere to rule on the dispute in question. But Brussels I (consolidated) never solved this issue to begin with, so how would Brexit or changes in English/common law worsen or improve matters?

Fourth, there is the matter of enforcement, which the article really gives short shrift to, but this is really the crux of the matter. In this regard, there are two situations I can think of in the case law: one is where a litis gets rejected by a local court claiming jurisdiction and the claimant wants to take the case to the specified jurisdiction instead. In these cases, the only recourse would be the court of instance’s appeals/cassation circuit, which in the best of cases would recur to settled European law, putting us once again back to Brussels I. Therefore, again, if the appeal is once more settled pursuant to settled European precedent, how does Brexit change anything?

Fifth, is the second matter of enforcement: arbitration. In this case, once again, contracts must include an arbitral covenant specifying submission to an arbitration court (and in commercial law there are oodles of contracts subject to an EU jurisdiction that nevertheless specify English arbitral tribunals for arbitration). In this case, Brussels I explicitly does not apply to arbitration– for exactly this reason: EU law is already accustomed to contracts being subject to one set of procedural laws and another set of arbitral rules. This means not only should there be no need for major accommodation of EU/English systems co-habitating (because they already do), but also that there is already both legal doctrine and case law in place for ruling on any such conflicts.

Overall, these are various diverse aspects that need to be discussed in-depth, and I imagine the author outranks me in expertise to deal with them, but as written the article (space limitations) does not go into enough detail to come to the conclusion that Brexit would predicate a major change in enforceability of UK judgments, or vice-versa.

I don’t see the issue at all except insofar that the EU would like to capture some of the international arbitration and lawsuit business. While I can speak only for commodity contracts, English law plus high court or arbitration are commonly used in contracts worldwide between any number of different corporations based in just about any country. I have worked on court cases involving French corporations suing Pakistani companies using English law and the high court.

English law and London are used for a variety of reasons, not the least of which are jurisprudence and a commercial approach to settlements. There is no incentive or reason for a company to choose arbitration in Paris with all its associated costs and regulations.

Not particularly applicable to the issues posed by Brexit, but . . . .

I am a member of the Louisiana bar. Louisiana is a civil law jurisdiction though that has been whittled away a bit with the state’s late adoption of the UCC and other matters. When I practiced it was not uncommon for out of state attorneys to be flummoxed when finding out that their out of state clients’ contracts with a Louisiana entity were governed by civil law as specified by the contract. Didn’t mean much in practice as they were forced to retain local Louisiana counsel in any case.

Where things got interesting was when our Louisiana client would sue a defendant in federal court in, say, Florida, and the local federal “common law” judge would have to litigate the issues in accordance with Louisiana civil law. The judge would find it entertaining, but his/her law clerks not so much as they were the ones who had to bone up and do the heavy lifting on legal research in a “foreign” area of law.

It’s not, of course, just a matter of jurisdiction shopping; the legal system and especially the judiciary must have a breadth and depth of experience to be able to hear the cases which inevitably arise and had down cogent judgments. The ridiculous nonsense which Justice Scalia came up with — slapping Obama in the face, too — in Argentina’s restructuring might have been technically defensible but went so far against established norms as to cast serious doubt on using NY as a governing law.

The UK Supreme had given a lot of thought to this and, if you read between the lines, makes a good play that a legal system which has its head screwed on is definitely a national asset.

This article isn’t the best organised, is it?

It moves from questions of enforcement to that of governing law, and then throws arbitration and language into the mix.

Yes, in theory, a case may under Brussels I be heard in French courts, but the governing law may be English law (be it by choice or by Rome I provisions). Or the English courts may be the forum, but the governing law French. What does this mean? Courts may already be applying different laws in their courts. In English courts, for example, proving a foreign law is fairly clear-cut. Nothing stops the French courts (for example) from having similar rules of court, with experts proving foreign law. I would be interested to know what, for example, the French rules on evidence are. I don’t think this article provides us with enough detail to actually support its contentions.

Also note that the EU is not the only place on earth where disputes arise. There are likely, to greater or lesser extents, rules in place to determine governing law and forum where the EU Conventions do not apply. I cannot speak to any of the civil law systems, but it is true that the English and Wales legal system is fairly certain in terms of determining these questions.

And then there’s enforcement, which is yet another separate matter. The EU and UK can negotiate a new bilateral treaty, which I do agree is going to be painful. But again, there are default laws in place to determine whether and how foreign judgments can be enforced. It’s not as if the EU only ever enforced EU judgments. Certainly the UK won’t have done so. And enforcement has never been universally easy, even when the UK was part of the EU — they aren’t just dependent on the laws of the enforcing country, but on more pragmatic issues like… does the judgment debtor even have assets? And so on.

Differences in procedure have always been there. Language differences have always been there. I think that, in this case, it’s easy to overstate the problem.

Aw, just expand the ISDS tribunal thing. Corps want rules of decision and enforcement mechanisms and places to engage in genteel trial by combat. The ISDS arbitrariation forum will give them everything they want. Maybe even reduce transaction costs(snort).

This is all just about elephants, mostly the engines of planetary destruction, just thundering around, crushing little creatures as they fight over the fodder and peanuts. Fiddling and grasping, while the zoo burns…

As to settlement (in all definitions) of derivative contracts, let them burn in h3ll.

As suggested here just move the cases to Dublin, as Ireland has the common law and a system of judges used to it. Might make money for Ireland if fees are high enough. Ireland is staying in the EU so the enforcement of judgements would not be a problem.

Does the Republic really have an off-the-shelf, ready to go legal system and the associated support services (lawyers, paralegals, case law, statutes, judiciary, infrastructure capacity…) to handle cases of the kind of complexity of, say, the Lehman Brothers insolvency?

Naturally, anything can be developed given enough time. But if have a multi-billion dollar liability you want settled, you don’t want to have to wait 10, 20, 50 or even a hundred years (English law has been developing since the 1600’s) while it all gets figured out as people go along.

If it can be said, and people are indeed rightly saying it, that this approach is not viable for complexities like Brexit, the same argument holds true for the legal equivalent of saying “let’s just put on the show right here on the sidewalk”. (or whatever your favourite version of the cliche is)

I’m sure you are right that Ireland doesn’t have the depth of legal capacity to take on the biggest cases, but I suspect the answer will be that since Dublin is only an hour from London, it can simply insist that the cases take place in Dublin, but everyone is free to hire UK lawyers and UK judges who qualify are free to apply for Irish citizenship. Its not unusual for London based law firms to work in Ireland on big cases – my own employer uses a large London based law firm for advice – when their small Dublin office is overwhelmed they fly in the bigwigs to deliver their sonorous advice.

That said, I haven’t even heard a whisper of any of this here, and I live in the ‘legal quarter’ in Dublin, right between the three biggest courts and the two law schools. But knowing the reputation of the legal profession here, if they suspect this is a runner, they will jump on it immediately and they have lots of contacts at the highest level of government.

That’s a slightly neoliberal view of the world though, isn’t it? Everything and everyone has their price, people only ever maximise their utility and you can move any process and all activities to whenever you want in the world. And it’s all frictionless.

Except it doesn’t always work quite like that. Sure, some specialist skills will be happy to move to (wherever). But different class and age demographics respond differently or don’t respond at all to pricing signals. Partners in legal firms, insolvency practitioners, research analysts and judges who are settled and have family commitments, cultural ties, investments in property or any number of reasons which aren’t solvable by price wouldn’t necessarily up sticks in the sorts of numbers needed.

Put it this way, I’m pushing 50 and apart from a final retirement move, no amount of money would induce me to move anywhere.

And it’s not just a matter of the people resources. Settled law requires both (in common law systems of justice) case laws and statutory provision. Supreme Court judges often make intentionally dumb-ass rulings precisely to force parliament’s hand in legislating where lawmakers have (due to political considerations or else just wanting to avoid difficult issues) tried to duck their responsibilities. And, conversely, where politicians have made what eventually gets determined by society, business or international standards to be bad law, judges curb the worst excesses through nuanced judgements which chip away at the statute.

One could even argue that Judge Scalia was doing that in the Argentina bond rescheduling. However, I would argue he was just being an idiot.

But that does illustrate you need both the legislature and the judiciary to provide effective legal systems for the complex contracts and cross-border entities we’re discussing here.

For Lawyers from London there would be no need to move, just use airplanes for commuting. Note that Ireland has had a common law system since at least the time of Henry VIII and was part of the UK until after WWI. (Anyway IMHO Dublin is a more livable town that London anyway).

I hate to break this to you, but I’ve done the international (in EU and beyond) exec lifestyle and it gets very tedious very quickly unless you get c-suite comp and/or are willing to trade your life for your job. I regularly did London to Edinburgh which I thought would be easier, but it really wasn’t and even Southampton to Manchester (about as short a flight as it is possible to have) is will-to-live sapping in the end.

You’ve got to get to the airport. I got taxis on expenses but it was still 30 minutes to an hour depending on which I was using (Southampton or Heathrow). Plus you’d have to allow another half an hour to 45 minutes for traffic contingency. Then, oh joy of joys, you have check in and security. Even if you have a business class lounge pass, it is simply tedious dead waiting time. The flight itself is the usual short-haul grimness and then you’re at the destination airport. You’ve got another taxi ride to your destination (30 minutes or so). End-to-end, best-case, the shortest journey time I ever achieved was three and a half hours, London to Edinburgh.

Then a days’s work. Then you have to do the return leg. You might well leave the house at 05:00 and not get back until 21:00 after which you were only up to falling asleep and hoping you didn’t need to do it again for a while. I shrugged it off in my 20’s, could just about do it in my 30’s and vowed never, ever to get on that treadmill again by my 40’s.

The other option is a hotel or city-pad accommodation. Hotels — and I usually booked into 5* standard — are in a very short space of time utterly dehumanising and soul-destroying places to live, long term. Okay, you can use your evening to explore the localities but you are not and never will be local. You simply cannot put down roots living out of a hotel nor do anything other than have a transitory existence. If you rent or buy a place in the city you’re working, that is only viable if you have a semi-fixed location and renting, let alone owning, brings its own share of hassles. It kills normal family life, your friendships and relationships suffer and forget about having any interests outside work like a pet, a garden, a serious hobby or anything other than planning your life by airline schedules and trying to keep fresh food in the refrigerator and buying two sets of everything important.

I do wish people who moot the possibility of a seriously large number of individuals saying “oh, that’s fine, we’ll just go live in Dublin / Berlin / Geneva / Wherever” or “people will just have 500 mile commutes” would try it first before offering it as a solution with widespread appeal.

Finally, urban Ireland has a population one twentieth of what is in London and the Home Counties. The notion it could have home grown experienced staff to replace 50,000 — let alone the much more realistic 100-200,000 which might be needed — legal and ancillary resources from the UK or could provide accommodation for them if they could by some fantastic notion persuade them to relocate is absolutely laughable. And as I said earlier, you need settled case law and legislative instruments — not just the same flavoured legal system.

Oh, I’m not suggesting its easy, or that its the right thing to do – I was more commenting on whether there will be a temptation for Ireland to try to pry this sector from London and if its practical. Irish commercial law is very similar to UK law for a wide variety of reasons, so there would be little practical issue in transferring it. As for barristers moving, the very few upper level barristers I came across in London seemed invariably to have houses out in the Surrey countryside or in the Cotswolds, and pied a terres in London, I’m not sure that a diversion to Heathrow on Monday morning would be a big change in lifestyle for them. So in practical terms, I would have thought the legal profession would much prefer a shift to Dublin than to Paris or Cyprus. But I know little about Commercial Law, so there may be good reasons why its not been pursued by Ireland at the moment.

The EU is the fascist fourth Reich coming to fruition. I hope Britain *completely* leaves this horrible slow-motion corporate coup. Who cares about common law when the EU has no respect for law. They recently pushed GMOs on the whole continent and now want to create a standing imperialist army:

http://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2017/06/24/euro-j24.html

Perhaps. Perhaps not. But a murder / suicide pact is not exactly destined to produce happy relationship outcomes. For either party.

The more complicated something is (or is portrayed to be) the more billable hours for lawyers. So my guess is that lots of hours will be billed, whether or not the hours are needed is not quite relevant – the hours were recommended by legal specialist just in case

Even health and safety legislation, much of which comes from eu,

overlaps with much older english common law which may not be ignored legally, by gov policy and guidance.

I have run across this with primary schools, english common law protected the parents interests and courts here have ruled in their favour. It took some digging to even find out the truth, nothing but misinformation from the council “It is very rare for school staff to be prosecuted under criminal law with regard to accidents involving children. Employers, school staff say and others also have a duty under the common law to take care of pupils in the same way that a prudent parent would do so.” So if a hundred parents object to something at the school on grounds of unproven safety, and the school says its safe, the parents can and do win in court, their concerns are prudent.