Yves here. I must confess that I have not read the underlying papers. However, I have every reason to think this summary is accurate. And if so, I see two shortcomings with this analysis and I welcome reactions from readers, particularly those familiar with that debate (or alternatively, the economy of Miami)

One is it does not appear to allow at all for macro trends. The immigrants arrived in 1980, the depth of a very nasty recession. Thus the extra workers were picked up in the vigorous and sustained economic upswing after it ended. The second is whether “Miami” can be treated as a discrete economy. How many low-end jobs are there with local employers who would and could drop pay, versus ones like McDonalds and national hotel chains which wouldn’t?

By Silvia Merler, currently an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel and previously an Economic Analyst in DG Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission. Originally published at Bruegel

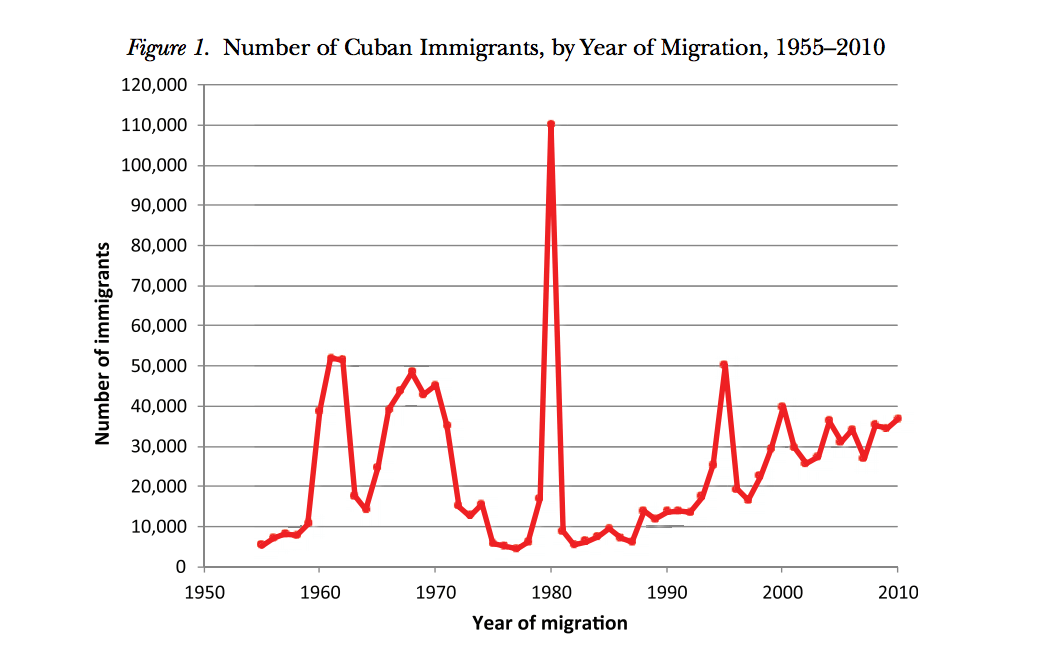

What’s at stake: how does immigration affect the wages of local workers? One way to answer this question is by exploiting a natural experiment. The Mariel boatlift of 1980 constituted an ideal experiment – bringing a sudden and large increase of low-skilled workers in just one city – but results are still hotly debated.

In 1980, 125,000 mostly low-skill immigrants arrived in Miami from Mariel Bay, Cuba (“Mariel Boatlift”) in the space of a few months. In 1990, David Card investigated the effects of the boatlift on the Miami labour market. The Mariel immigrants increased Miami labour force by 7%, and the labour supply to less-skilled occupations and industries by even more, because most of the immigrants were unskilled. Nevertheless, Card concluded that the Mariel influx had virtually no effect on the wages or unemployment rates of less-skilled workers, even among Cubans who had immigrated earlier. Card suggested that the ability of Miami’s labour market to rapidly absorb the Mariel immigrants was owing to its adjustment to other previous large waves of immigrants.

Source: Borjas (2015)

Ethan Lewis evaluates two explanations for Card’s result: (1), whether after the boatlift Miami increased its production of unskilled-intensive manufactured goods, allowing it to “export” the impact of the boatlift; and (2) whether Miami adapted to the boatlift by implementing new skill-complementary technologies more slowly than they otherwise would have. Lewis’ results suggest that wages are consistently found to be insensitive to local immigration shocks because markets adapt production technology to local factor supplies. Bodvarsson et al. argue that one reason immigration has no evident negative effect on the wages of locals is that immigrants as consumers contribute to the demand for their services. They model an economy where workers spend their wages on a locally produced good, then test it via a reexamination of the Mariel Boatlift and find strong evidence that the Boatlift augmented labour demand.

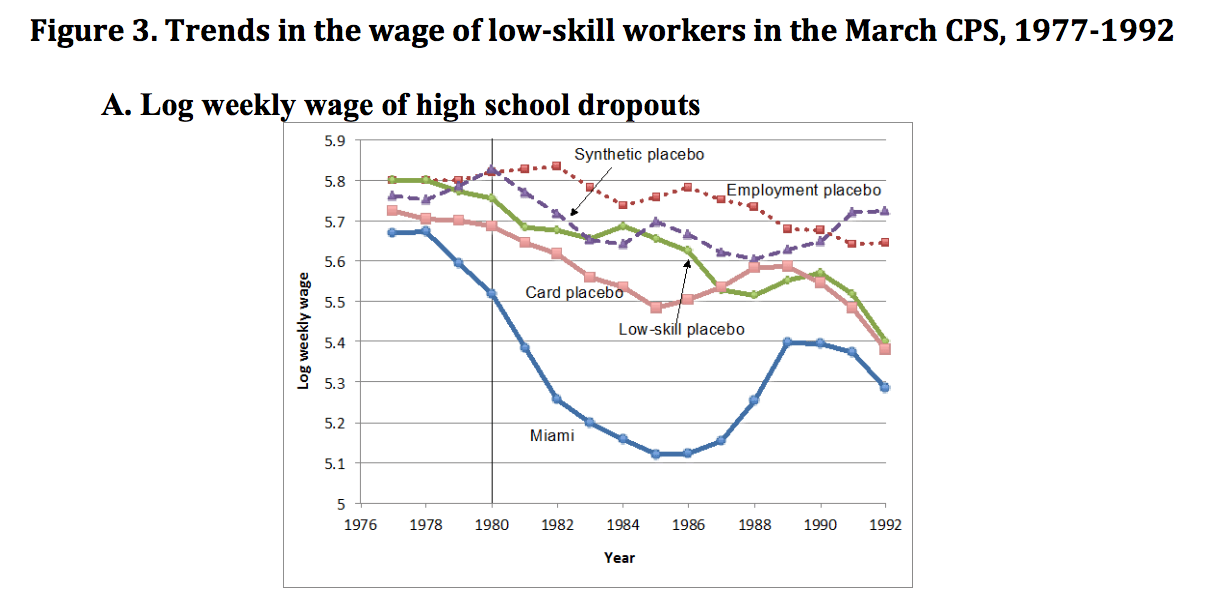

In 2015, George Borjas published the first version of a paper that was overturning completely the results of the previous literature on the Mariel supply shock. Borjas argued that any credible attempt to measure the wage impact must match the skills of the immigrants with those of the pre-existing workers. At least 60 percent of the Marielitos were high school dropouts, and specifically examining wages in this low-skill group suggests that Mariel did affect Miami’s wage structure. The wage of high school dropouts in Miami dropped dramatically, by 10 to 30 percent (depending on which control “placebo” groups is employed).

Source: Borjas (2015)

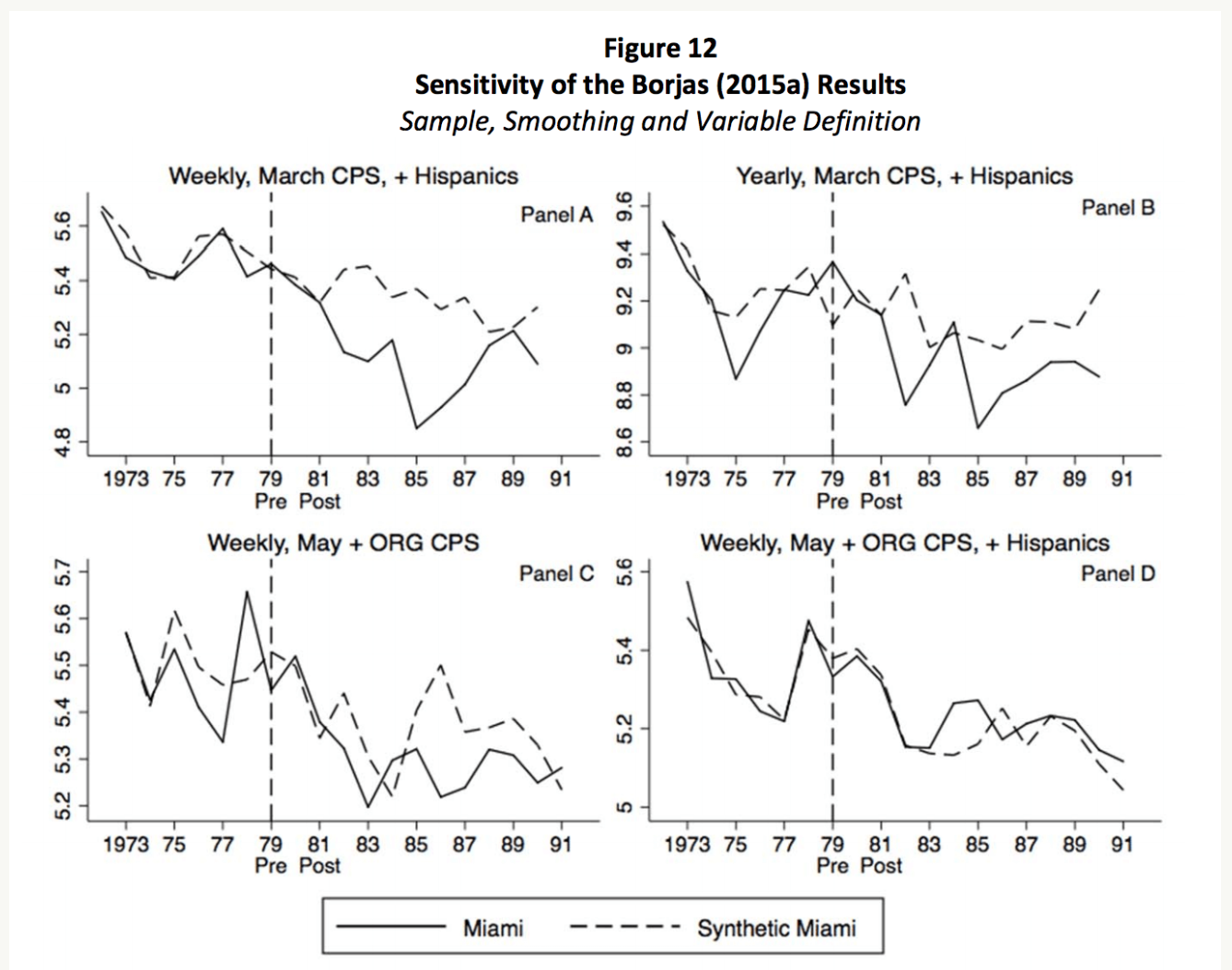

In 2015, Peri and Yasenov re-examined the wage and employment effect of the Mariel Boatlift, by using a synthetic control method to choose a control group for Miami so as to best match its labour market features in the eight years before the Boatlift. Analysing wages and unemployment rates they found no significant departure between Miami and its control from 1980 to 1983.

Source: Peri and Yasenov

Peri and Yasenov also replicate Borjas’ results (figure above), and find that a large negative deviation of wages of high school dropouts in Miami arise only when using the March Current Population Survey data. Moreover, the deviation is significant only in a sub-sample obtained by eliminating women, non-Cuban Hispanics and selecting a short age range (25-59 years old) among high school dropouts. These very drastic choices leave the sample in Miami as small as 15-20 observations per year and measurement error in average Miami wages can be in the order of 20-30% for such sample. They argue that these restrictions are problematic because they eliminate groups of workers on which the effect of Mariel should have been particularly strong. They show that by adjusting Borjas’ sample to include these sub-groups of high school dropouts or looking at alternative outcomes, the post 1979 Miami-control differences vary widely (negative to zero to positive) if using March-CPS data.

Borjas answered with a second paper, intended to isolate the source of the conflicting results. He argued that the main reasons for divergence are that Peri and Yasenov calculate wage trends in a pooled sample of men and women, but ignore the contaminating effect of increasing female labour force participation. They also include non-Cuban Hispanics in the analysis, but ignore that at least a third of those Hispanics are foreign-born and arrived in the 1980s. Lastly, they include workers aged 16-18 in the sample. Because almost all of those “workers” are still enrolled in high school and lack a high school diploma, this very large population of high school students is systematically misclassified as high school dropouts. Borjas argues that this is a fundamental error in data construction, which contaminates the analysis and helps hide the true effect of the Mariel supply shock.

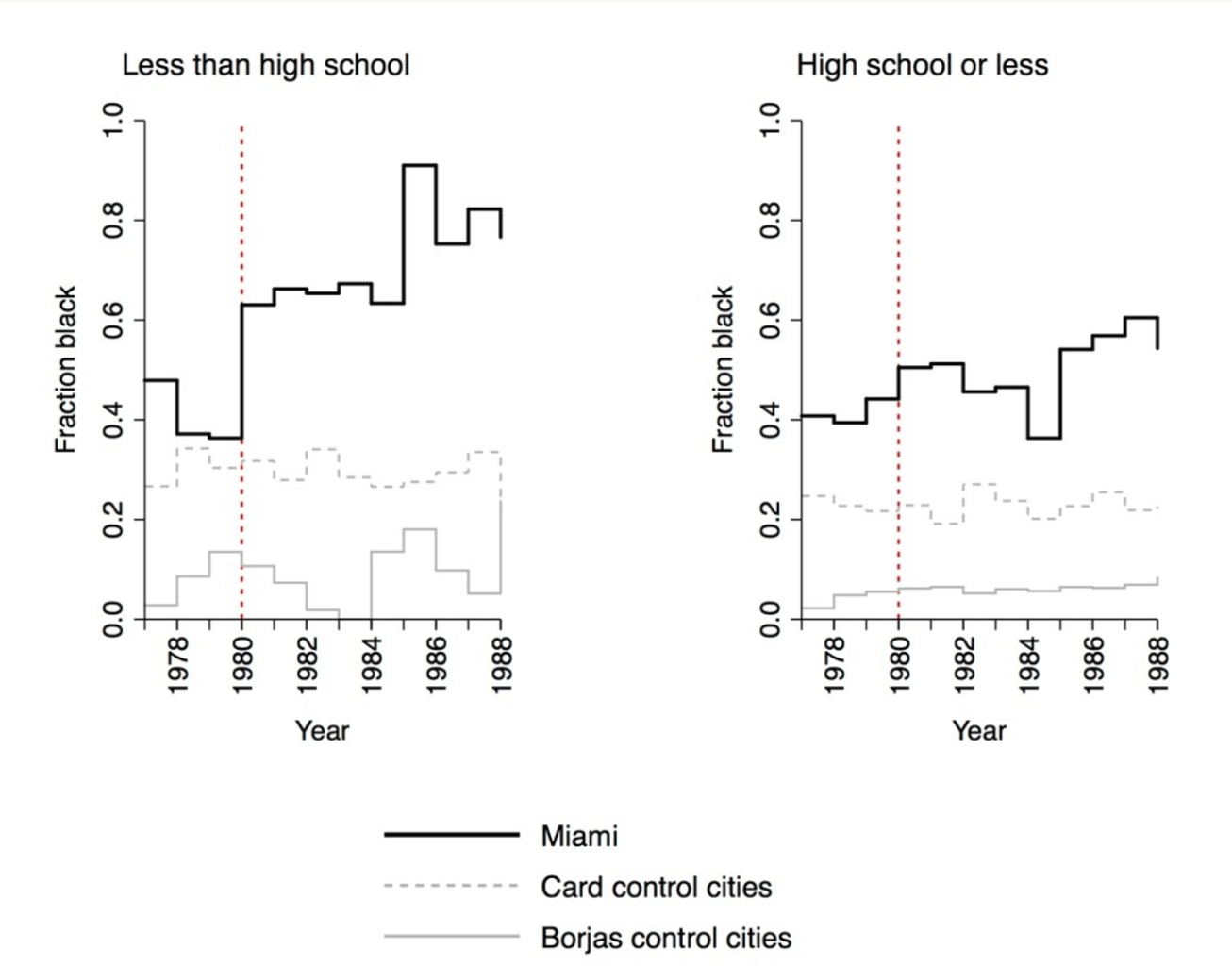

More recently, Clemens and Hunt argues that the discrepancy between Card’s, Borjas’s, and Peri and Yasenov’s analyses of the Mariel Boatlift can be explained by a sudden change in the race composition of the data they all use, i.e. the Current Population Survey (CPS). This survey happens every month; and two datasets taken from the CPS also report workers’ wages (the ‘March Supplement’ and the ‘Outgoing Rotation Group’, ORG). Clemens and Hunt point out that in 1980, the CPS survey methods was improved to cover more low-skill black men, which had been undercounted previously. Starting in the 1981 CPS, survey coverage of lower-skill black men shifted to include relatively more black men with less-than-high-school, and relatively fewer black men who completed high school (see figure below).

Source: Clemens and Hunt (2017)

So in 1980, coinciding exactly with the Boatlift, the fraction of non-Hispanic blacks suddenly doubled in the subgroup of Miami workers with less-than-high-school analysed by Borjas (2017). No such increase occurs in the subgroup of natives with high-school-or-less analysed by Card (1990) in the same dataset, nor in the control cities favored by either Card or Borjas. Clemens and Hunt argue that due to the large wage divergence between black and non-black workers with less than high school, this sharp shift from majority non-black in 1979 to majority black in 1980 and almost entirely black by 1985 can account entirely for the magnitude of the effect measured by Borjas (2017) relative to the null result of Card (1990). The wage drop identified by Borjas would therefore be entirely spurious. Borjas methodological response and Clemens and Hunt methodological counter-response can be found here and here, respectively.

I lived in Miami Beach soon after the Mariel Boatlift. The number of undocumented, and off the rolls low wage workers was large. (I was in plumbing at the time.) The Haitians were “coming into their own.” The local phrase was; “F— this job! Get a Haitian!” Many of the Haitian workers were “illegals,” and competed with the other low wage workers for what was available.

So, the Marielitos were a big blip in a continuing saga of low wage worker saturation in South Florida. My question would be; what adjustments to the data sets were used to account for the “off the books” part of the working population?

Almost by definition, the Marielitos and Haitians were desperate people. Such people will do “what it takes” to survive. That includes working for next to nothing, which requires “off the books” arrangements.

Another seldom mentioned aspect of the Mariel boatlift is class. The old line Cuban Refugees were for the most part the “Doctors, Lawyers and Indian Chiefs” from the pre Castro Cuba. The Marielitos were considered by those older cuban exiles as the “Cuban scum of the earth,” and treated as such. My anecdotal information tells a tale of a displaced elite class from cuba, living in Florida, replicating the attitudes of the old social system they had been ejected from.

Finally, remember that the Mariel Boatlift was a master stroke by Castro. In one fell swoop he emptied his jails of his petty criminals, and sowed dissention and chaos in the Cuban Exile community in South Florida. He also displaced a major social problem and budgetary problem from cuba to the United States. I read that there are still Mariel Boatlift “undesirables” being held in Federal prisons in the South.

My question exactly. I too have spent a lot of time in jobs where competition with immigrants was discussed daily. I often wonder if economists appreciate just how large the off-the-books economy actually is, and how vital to acquiring needed cash in a pinch even for many people with on-the-books work.

Yes, I think there are all sorts of things pretty unique about Miami that makes it difficult to interpret the data. Also, as WG says below there was a lot of cocaine money coming in at that time, which is bound to have had an impact. There is also an ‘ethnic’ element to employment where an influx is often helped/employed/exploited by the first generation who have businesses, and much of this occurs on a second set of books (i.e. illegal employment). There is also the reality that people on minimum wage may be officially paid the minimum wage but may have illegal deductions – this is particularly common when a first generation of immigrants arrive and haven’t fully established their rights. So a reduction in wages may have occurred without showing in official figures.

I just watched the documentary “Cocaine Cowboys” on you tube after reading this post. It documents the massive influx of drug money coming into South Florida around this time. Surely that money would have helped to support the local economy. Some of the stories told are crazy, but worth watching.

Analyzing complex phenomena such as this is very tricky, and Yves asks some good questions in her second paragraph. I lack the expertise to comment authoritatively on this, but I do have an impressionistic observation. This reminds me of the apparent hiatus in global warming during the first decade of the 21st century. It turned out, this apparent pause in warming wasn’t real, and was really an artifact of a change in the way that ocean temperature was measured. This was discussed in comments to the Links on Jan. 11, 2017:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2017/01/links-11017-2.html#comment-2741910

Here’s the article that was being discussed:

http://therealnews.com/t2/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=31&Itemid=74&jumival=18075

The back and forth between Borjas and Clemens & Hunt resembles the disagreements about the global warming pause. I’m not sure which side of the global warming debate corresponds to which side of the Mariel immigration debate, though. My naive intuition tells me that if the supply of workers is significantly increased in a short amount of time, then wages will either drop, or an existing increasing wage trend will increase by a lesser amount.

It could be that something unusual was happening in Miami in 1980 that could confound the analysis.

http://www.unz.com/isteve/the-ignorance-of-economists-refugees-cocaine-and-miami-in-1980/

http://www.unz.com/isteve/was-there-anything-unusual-about-miamis-economy-in-1980-84/

Gold !

Having read the underlying papers, my impression was that some very remotely relevant data was tortured until it revealed “conclusions” that might have had something to do with the data but that certainly had a lot to do with the underlying assumptions and methodology. An interesting exercise but by no means persuasive or definitive. To his credit, Card was explicit about the tentativeness of the findings. I don’t recall Borjas being as modest.

The reception of Card’s paper is another matter entirely. The conclusion has been cited extensively as PROOF! positive that increases in the supply of labor have no effect on wages and/or unemployment because “supply creates its own demand.” A classic case of confirmation bias. The study is a celebrity precisely because it seems to confirm what economists wanted to see confirmed.

For several years now, “natural experiments” have been hailed as the silver bullet to determine empirically how socio-economic mechanisms work. I have always been doubtful, and the present case illustrates the difficulties of performing those alluring “natural experiments”.

1) The system under observation is not closed.

E.g. population flows between Florida and the rest of the USA.

2) It is influenced by forces orders of magnitude larger than the effect under observation.

E.g. the global downturn in 1980 that reversed in the following years, the long-term rise of women participating in the labour force.

3) It is not clear how to categorize the entities under observation.

E.g. women and men together or separate? What to do with the 16-18 years old? And what kind of equivalence between Cuban educational achievements and the USA ones?

4) Actually, a significant part of the population impacting the measurements is not captured or observed at all.

E.g. illegal Haitian immigration that occurred simultaneously, in the same location, and concerned similar employment sectors.

5) The measurement scales changed mid-course.

E.g. the change in the composition of the black population in the underlying surveys.

6) The underlying explanatory mechanisms have not been cleared up empirically, and remain purely hypothetical.

E.g. do production process in various sectors adapt to take advantage of a larger supply of labour with specific skills (or lack thereof), or is a pure supply-demand mechanism at work?

7) It is unclear how the experiment can be generalized.

E.g. the case in point concerns a sudden, brief immigration spike, not a sustained immigration flow over a long duration, whose effects might be very different (see point 6).

The methodological debate exposed in the article is actually quite interesting. The nooks and crannies of how to analyse socio-economic data are intriguing. No surprise that economists prefer to tinker with completely abstract, unrealistic mathematical models on their computers rather than deal with the messy, complex, incomplete, inter-related data to determine how the real world functions.

The provisional conclusion I draw from that discussion is that we just do not really know how immigration impacts the labour market.

“what” an economist says is not so interesting,

“why” is more so.

or, who is paying him?

Thank you Yves, very interesting summary!

Regarding the macro, it’s supposed to be taken care of by looking at the difference between Miami and ‘placebo’ group, is there a reason to suppose that the recovery affected Miami more than the comparables? I don’t know.

It is wonderful for employers the way skilled jobs become unskilled if performed in good weather.

I’d say that jobs below the Mason Dixon all pay less and any excuse, be it Cubans, Haitians, people from Alabama or Mars, will be used to justify lower wages for workers.

How much wages below the Mason Dixon depress wages North & West is a better question. Certainly when it comes to the making of cars we saw that happening in memory when parts of Detroit operations were moved to Southern States & Mexico.

For people who do not compete for the sorts of jobs they are supposedly studying to say that more people competing for jobs of a certain sort in the same places doesn’t matter means simply they are not really studying the issue, since it doesn’t matter, to them.

I can say from my experiences in aviation ground services & motion picture production that pay for motion picture technical support positions in the rental house was a good deal lower than comparable work in NYC.

Aviation is one of those areas where wages have not gone up in 30 or 40 years so it hardly mattered but I tell you small businesses thought nothing of offers below minimum wage.

If one is seeking the effect on wages due to the importing of foreign labor then one need look no further than the H1-B devastation in the IT industry. There is plenty of data available from the DOL. I am a recent casualty. I just completed my PhD in Digital Communication and have around 23 years of experience as an embedded systems software engineer (once very hard to find people). I also have a double bachelors in Physics and Electronics Engineering, an MBA and an MS in Electronics. However I am on the wrong side of 50. I still have not found a contracting gig after a 2 month search. I get calls mostly from Indian companies like HCL, Wipro, Tech Mahindra, TCS etc. They all are trying to fill slots in companies like Intel, Delphi Automotive, Ford, GE etc. I am holding tough at $60 per hour but all my offers are in the $50 range. What is happening is a perverse kind of oligopoly where the big MNCs turn over en masse their short term positions to these Indian companies and since there are only a handful of them, they collude to keep the hourly wage rate down because they can always import engineers using H1-Bs if needed. Now I cannot directly prove this but I am very certain that they carry out faux candidate searches and interviews to fill paperwork to prove to the DOL that they are unable to find anyone and hence the need for a H1-B to import a foreign candidate. I have a nephew who has been farmed out to British Telecom by TCS. He is stationed at Ireland and has been there for sometime now after a 1 year stint sometime back. I feel sorry for the Irish engineers. Indian Engineers are decimating the labor market in IT and also high tech all over the world. They are devastating an entire generation of young locally educated engineers everywhere. What happened earlier in the meat packing and unskilled labor market has now been happening to the high tech sector for 3 decades with nary a whisper or protest from any of the groups like IEEE or ACM etc.

The IT industry is turning into a nightmare.

Any help on how one can exit it will be most welcome.

All your experience mounts to nothing, and every two years there is a complete reset just for the sake of change. It is just a way of depreciating tens of thousands of man hours of experience, and making you valued the same as a 21 year old who drops the latest buzzwords.

Now the buzzword is “AI, Machine Learning, Cognitive Computing (!)”. And NOT ONE product uses these technologies.

There is no requirement that H-1B employers conduct a test of the labor market by advertising the position to see if U.S. workers are available. You’re confusing that with employers looking to sponsor foreign workers for permanent residence, for which such a test is usually necessary. It’s an honor system subject to audit, and any employer depending on foreign labor would not want to risk getting caught.

This is the glory of the neoliberal system! American high tech corporations benefit from global marketplaces, and they benefit from global labor! Everyone* wins!

* everyone as in “owners of capital” (the only people who matter)

With these studies, they do not attempt to quantify the externalities of which economists occasionally mention.

Immigration may also hit native low wage workers with other non-monetary costs that lower their living standards.

They may have their commutes take longer with the additional workers on the road and their public schools, public transit, public provided health care, and public parks may be more crowded/more financially stressed as well.

The well-off that benefit directly/indirectly from an influx of low wage labor can compensate via private schools and by residing in higher end neighborhoods that benefit from low wage labor for domestic help.

For example, a public park in the well-off city of San Marino in Los Angeles County has an access fee of $4,00/person for non-residents to use the park on Saturday/Sunday.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lacy_Park.

This tends to keep lower wage families away from this park during the time they would want to use it, the weekends.

But the park access is free for San Marino residents at any time.

For what it is worth, the San Marino Park receives both state and federal money for maintenance –

Also, I don’t think one can study the impact of immigration in states like Florida, or Texas, and the Southwest – their economies are built on this labor and the movement of people across water or land borders. This is why for the exception of the prison/detention complex folks, their local economies may very well/is likely to tank under Trump.

There is no solution to this other than a federal guaranteed job program, funded by a differently designed fiscal policy.

As a resident of Tavernier (mile marker 93) from late 70’s to mid 80’s, the Mariel boatlift marked the end of the Keys ambience.