By Daniel Gros, Director of the Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels. Originally published at VoxEU

Trade liberalisation has been a significant driver of globalization over the past half century. However, global trade has slowed down in recent years. This column argues that globalization can also be driven by higher commodity prices can also drive, as commodities constitute a large fraction of global trade. This is reflected in trade volumes and commodity prices, which increased until around 2014 but have fallen since. However, commodity price-driven globalization implies lower living standards in advanced countries, as the higher commodity prices diminish the purchasing power of workers.

Trade and international financial transactions have grown massively in recent decades. This phenomenon, also called globalization, is often described as a ‘mega-trend’. Business and political leaders never tire of repeating that ‘globalization’ is the future, that it delivers more jobs and higher incomes. However, more recently globalization seems to be in retreat—in 2015 trade actually fell, both in absolute terms and relative to GDP. Does this mean globalization has gone into reverse (OECD 2016, IMF 2015, 2016)?

In this column, I argue that the slogan ‘globalization equals growth’ is wrong. There is no general economic theorem that links more trade to growth and other economic benefits. Economic theory implies only that, under most circumstances, lower trade barriers will lead to more trade and more jobs. The simplification, that more trade is thus always beneficial, is not warranted. If trade increases for reasons other than the lowering of trade barriers, it is far from clear that this will benefit everybody.

The distinction between globalization driven by lower trade barriers and increases in trade driven by other factors is not just an academic point. It is the key to understanding why globalization has become so unpopular in most advanced countries, and why the recent slowdown in trade is not something to worry about.

What Drove ‘Hyper-Globalization’?

The massive increase in trade flows over the last two decades has always been difficult to explain with ‘classic’ causes, such as trade liberalisation lowering trade costs. Tariffs (and other trade barriers) had of course been reduced radically in several stages in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. However, by the late 1990s the remaining tariffs were already rather low; and many non-tariff barriers (such as the Multi Fibre Arrangement, which had seriously limited trade in textiles) had also been eliminated.1

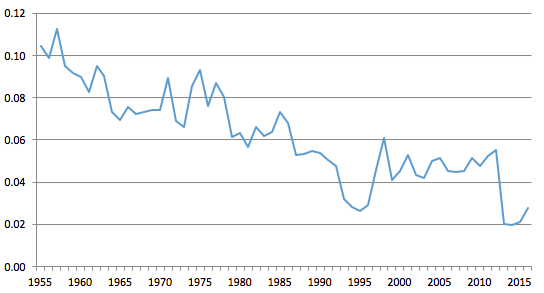

Transport costs of course fell with containerisation, but this improvement had yielded most of its benefits by the late 1990s. Estimates of the overall cost of trade based on the ratio of CIF prices (which incorporate transport costs) and FoB prices (which do not) actually suggest that transport costs slightly increased over the last 20 years; before1995 they had fallen almost continuously (Baldwin and Taglioni 2004). Figure 1 shows that transport costs have fallen again very recently, but that this coincided with a slowdown of trade – the opposite of what one would expect.

Figure 1 Word transport costs

[Imports(CIF)/Exports(FoB]-1

How can one reconcile ‘hyper-globalization’ (Subramanian and Kessler 2013) with stagnating tariffs and transport costs? Baldwin (2017) provides one answer. He argues that the key driver of globalization today is the falling price of ‘transporting’ ideas, as opposed to the cost of moving goods.

This contribution provides an additional, maybe complementary, explanation—higher oil (and other commodity) prices increase both trade volumes and transport costs for goods, but not ideas. The impact of oil prices on transport costs is clear—fuel is an important element of overall transport costs. A sharp increase in fuel prices can more than outweigh, at least in the short to medium run, the costs savings due to containerisation. (Cosar and Demir 2017 also argue that most of the cost savings from the latter have been realised.)

But the key point is that higher commodity prices also automatically create more trade, because commodities constitute a large fraction of global trade.

An Illustrative Example

Assume that one tonne of steel and ten barrels of oil are needed to produce one car. In 2002-03, that bundle of raw materials was worth around $800, or about 5% of the value of a car priced at $16,000. This implies that during the early 2000s, industrialised countries had to export five cars for imports of 100 bundles of these raw materials. By 2012–13, the value of the raw materials needed for one car increased to about $2,000, now representing about 10% of the cost of a car (prices of cars had gone up much less). Industrialised countries thus had to export 10 cars, double the previous quantity, for the same amount of raw material imports.

This example shows that the value of trade would double if commodity prices double. There is thus a direct link between the growth of trade and commodity prices. Increasing commodity prices lead to more trade (globalization), whereas falling commodity prices have the opposite effect.

An immediate objection to this example is that it looks at the value of trade, but one also finds that over the last decades the growth of trade in volume has exceeded that of the volume of real growth. However, this excess growth in trade volume also follows in this example—an industrialised country would need to double its exports in volume just to pay for an unchanged volume of raw material imports.

Since food, fuels, and raw materials make up about a quarter of global trade, the huge price movements in raw materials, especially energy, over the last few decades, must have had a big impact on aggregate trade figures. The run up in commodity, and especially crude oil, prices until about 2014 drove hyper-globalization, and the fall in prices since then has now reduced globalization. There is thus little need to look for other explanations for the recent slowdown in trade.

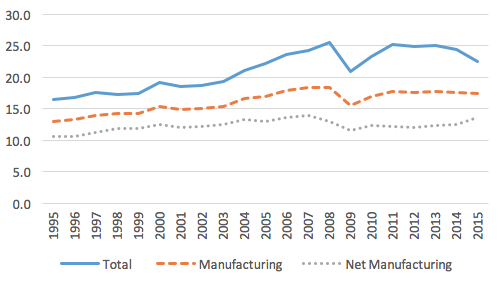

Figure 2 illustrates this phenomenon with three lines, each of which show three variants of the global trade/GDP ratio. The top-most line is just the ratio of total global exports to global GDP. It is the one that shows most globalization—trade accounted for a little over 15% of GDP in 1995, but 25% at the peak in 2007 (an increase of almost 10 percentage points).

The middle line shows global exports of manufacturing goods as a percentage of GDP. The difference to the first line is, of course, trade in raw materials, which increased in value along with their prices, as argued above. Trade in manufacturing goods shows much less globalization, having increased from only 13% to 17.5% of global GDP.

The lowest line takes into account the fact that higher raw material prices also means that industrialised countries have to export more manufacturing goods to pay for their more expensive raw material imports. This last line, which could be called ‘manufacturing trade net of payment for raw materials’ shows even less globalization, with the ratio relative to GDP going from 10.5% to 13.6% of global GDP (an increase of only 3 percentage points, one third of the headline increase mentioned above).

Figure 2 World trade as a percentage of GDP

Source: Own calculations based on OECD and WTO data.

This decomposition of trade flows suggests that there has indeed been some globalization, but it has been much less strong than the hyper-globalization one sees in the aggregate data. Moreover, the recent fall in commodity prices can fully explain the fall in trade since 2014 with trade in ‘net manufacturing’ showing no ‘de-globalization’.

But back during the heyday of hyper-globalization, no responsible politician dared to explain that globalization driven by higher commodity prices would have different implications (for advanced economies) than globalization driven by trade liberalisation—this new globalization meant lower living standards in advanced countries as higher commodity prices diminished the purchasing power for OECD workers. The widespread popular disenchantment with globalization can thus be easily explained—workers in Europe and the US were told that more trade would make everybody better off. But in reality there was no ‘surplus’ to be distributed, and workers just noticed a decline in their living standards.2

But hype and exaggeration are sure ways to bring a valid cause into disrepute. This is what has happened to globalization. The decades of gradual liberalisation of trade and capital flows that followed post-war reconstruction fostered a resumption of global trade that was hugely beneficial. However, at exactly the point when economic analysis would suggest that these gains from trading more freely were largely exhausted, actual trade accelerated. This surge in trade was driven largely by higher commodity prices and could not deliver higher living standards for workers in industrialised countries.

A popular backlash was thus unavoidable and Donald Trump became its standard bearer. The political consequences in Europe are also visible—the Brexit referendum, the difficulties in ratifying the free trade agreement between the EU and Canada (CETA) and the stand-still in the negotiations on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) between the EU and the US are all expressions of this disenchantment with globalization.

What Could Be Done to Avoid Throwing the Baby Out With the Bath Water?

A first step would be to stop the overselling. CETA and TTIP would be useful to have, but the economic benefits can only be of second order importance (and the potential damage feared by some as well). A second step would be to look where there are still trade barriers whose removal could bring significant welfare benefits. They are likely to be found in emerging markets, whose tariffs and non-tariff barriers are still several times higher than those of the EU or the US. European trade policy should thus concentrate on free trade deals with India or China, rather than the US.

See original post for references

Silly boy! What makes you think that Globalization was ever meant to grow “economies”? It was never more than a means for mega-corporations to improve their bottom lines………just another form of arbitrage….

Globalization and the “free trade” it espoused were – in the words of economist Ha-Joon Chang – tantamount to ladder-kicking:

“His conclusions are compelling and disturbing: that developed countries are attempting to ‘kick away the ladder’ with which they have climbed to the top, thereby preventing developing counties from adopting policies and institutions that they themselves have used.”

What Drove ‘Hyper-Globalization’?

What a silly question!

Inflating financial assets — theirs (the super-rich), not ours!

The inclusion of the fatuous ‘trade in money’ that our agreements contain suggests you are right. Ripping-off by agreement might be the new game.

Yes, it’s surprising how most politicians and economists have missed this. Globalization was always meant to grow corporate revenue in their home saturated markets. Their effects on their home countries’ welfare or their home country employees was not important.

Trump voters showed us otherwise.

Also, mergers are not about scale economies or some market benefits. Mergers and acquisitions are about letting top execs ask for higher benefits.

It’s amazing that few see thru this persiflage.

Which corporations have “home countries?” Any more than “our” empire is any respecter of silly old national boundaries. Nations were and are just springboards for “commercial interests…” https://www.librarything.com/work/73551 They’re the substrates that made and make “legal” the giant falsehoods and frauds that are corporate persons…

Theres a reason corporations are called ‘multinationals’. They don’t have actual ‘home countries’.

Once upon a time, we older people learned about MNCs and their penchant for playing countries off against one another. That seems so quaint in retrospect, given the more brazen behaviors on offer. More recently, families give up citizenship to save some wealth and to hide some wealth. To what kind of world are they running? When loyalty, duty and character become passé, then the replacement characteristics are cause for alarm and disgust.

My overall takeway — Decisions by large corporations have huge consequences for the locals, especially if their jobs swim overseas. Locals’ feelings at some point, maybe years later, become their votes and political opinions.

So if this is correct, Trump is the payback, greatly delayed. B Clinton’s and Obama’s politics changed our economy and that in turn became the new politics.

So economics has become politics, and not for the better.

There was a surplus alright. But even if promised to “everybody” it didn’t go and wasn’t intended to go – to “everybody”.

Workers without jobs not only can not enjoy the fruits of globalization (AKA lower prices by employing the ‘slave labor’ of developing nations and raping and pillaging their environment). Western workers can not pay into their (unlocked by resident politicians and oligarchs) ‘Social Security lock boxes’.

I don’t get a couple of things said in this post:

1. How come the huge run-up in commodities didn’t translate to higher (measured) inflation? The author even makes the point that car prices went up much less than steel and oil. (Also, the doubling of oil and/or steel prices seems strange to me, as I thought neither had seen a big run-up in this period.) Granted problems with measured inflation but clearly the bigger problem with working class real wage growth was wage pressure, not inflation pressure.

2. The author seems to presume that trade must balance within countries: exports of cars must double to pay for higher commodities costs. That certainly does not explain car exports from the US (not to mention the lack of balanced trade). And I don’t think it explains car exports from Europe or Asia either, unless the argument is that higher commodities costs affected exchange rates, lowering them for car exporters compared to commodities exporters. Nor would it seem to explain Chinese exports, again unless there is some argument as to why China “needs” (in an economic, not political, sense) to run a particular level of massive trade surplus.

3. The author completely ignores China’s accession to the WTO in 2000, which some recent studies have suggested was the primary driver for dramatic increases in China exports to US from that point.

The lack of car inflation may be explained by the increase in the same period in auto loan debt. If you can make a hefty profit off the loan interest and other service fees, they you don’t need to increase the base car price. There may even be a motivation to keep the prices low, as the cheap sticker price gets the customers in the door, and it’s not until they’ve gone through the ringer with the salesman and loan guy that they realized they’ve been duped into paying way more than advertised.

1. By globalizing wages downwards.

There are a lot of things said in this post that I don’t get. [And is this guy really Director of the Centre for European Policy Studies, Brussels? That’s scary!]

This author explicitly equates trade with globalization and implicitly equates growth with increases in GDP figures. I believe the term “globalization” covers much more than trade. I believe it also includes the deliberate movement of production out of the U.S. [or out of Europe] to far-away lands with cheaper labor and fewer annoying regulations. I believe it also includes an intent to weaken labor and nation states.

I doubt that figures for GDP provide an adequate measure for growth and similarly doubt that trade measured in terms of a currency provides an adequate measure for trade. Although I suppose this way of measuring trade might support the assertion:

“But the key point is that higher commodity prices also automatically create more trade, because commodities constitute a large fraction of global trade.”

I don’t know what that assertion really means given my bias against the measures this author uses. In turn, this assertion leads to another odd assertion:

“This example shows that the value of trade would double if commodity prices double. There is thus a direct link between the growth of trade and commodity prices. Increasing commodity prices lead to more trade (globalization), whereas falling commodity prices have the opposite effect.”

So using the authors terminology I have trouble with the assertion: “Globalization equals growth” is wrong. If globalization means bigger trade numbers and growth means bigger GDP numbers and if trade is a positive additive component of growth the assertion that globalization equals growth — more clearly — that globalization increases growth seems a tautology. The author’s slight of hand correcting for “higher raw material prices” in the trade figures does not convince me of the title assertion — and by this point in the argument the assertion — whether true or false — is devoid of meaning for me.

As Thuto notes in a comment below the author assumes globalization driven by trade liberalization is “somehow better” — I would say the author tacitly assumes globalization driven by trade liberalization does equal growth — contribute to “true” growth. This leads to the author’s conclusion that CETA and TTIP might have some marginal benefits and might cause some marginal potential damage … neatly avoiding the non-trade issues in those deals — like the ISDS “investor-state dispute settlement” and various intellectual property enhancements contained in the TTP. Given that globalization by trade liberalization does grow GDP and assuming that growing GDP is a good thing for all parties the author can conclude that “European trade policy should thus concentrate on free trade deals with India or China, rather than the US.”

We know how globalization’s free trade deals with India or China benefited the US. Does this author really desire similar benefits for Europe?

I’m with you Leftie. How inflation hardly appears in our hugely inflated western economies is one of the greatest magic tricks. We all know food and clothing has got more expensive but “inflation?” – not a hint.

I am guessing its like the paper gold market. We have the means to mis-price everything.

1. The CPI measure of inflation excludes most commodities, such as oil.

Conditions under which trade between nation-states is beneficial to both partners:

(1) Each nation exports goods which it has a competitive advantage in producing. Agricultural products are the classic example.

(2) The profits from sale of such goods remain in the country of origin. Transfer of profits out of the country of origin mean that the country is just a plantation run by absentee landlords.

(3) Trade between the nation-states must be balanced on both sides; i.e. exports and imports are on the same scale.

(4) Both nation-states must have a condition of full employment.

(Ricardo 1817)

Only when conditions 2-4 are met will condition 1, the ideal situation, be realized. Now, globalization of capital flows across nation-state borders (the key element of neoliberalism, or neocolonialism) defeats this. Instead of trade between independent nation-states, what we have is the imperial system – backed up by a $600 billion yearly military budget that is used to attack any entities that refuse to go along with the program, by covert means such as destablization and ultimately by military assault (as long as the target does not possess nuclear weapons, that is).

Furthermore, late 19th-century and 20th century economists have created a set of false assumptions and theorems with no basis in reality to justify this kind of thing. Notions like ‘utility’, ‘externalities’, and ‘GDP’ are just sloppy propaganda games; there are no ‘general theorems’ in economics that have any solid basis in reality – the entire game of modern academic economic theory is nothing but smoke and mirrors, whose primary function (as with Soviet economic theory and communism) is to promote the ideology of investment capitalism, protecting shareholder interests in the corporate system. If economists want to put their discipline on a sound physical and mathematical basis, they should start by studying a real science like ecology in natural science departments. My own opinion is that anything written by academic economists from the latter half of the 19th century to the present can be discarded with no loss at all.

Instead, read an ecologist like Hutchinson, and think about how those real concepts (in which there are no ‘externalities’) would apply to a study of human economic activity.

Globalization favored Mega Corporations and Multi-Nationals (+ their corporate share holders, lenders) over the rest of the society including labor b/c global labor wage arbitrage!

Living standards went down for working blue collar ( and some white collar) in the West. There was some ‘patchy’ RELATIVE increase in living standards of their middle class in some of the Countries, like India!

Sad reality:

The CAPITAL is mobile but the LABOR is NOT!

The author seems to be arguing that globalization driven by trade liberalization is somehow better and more palatable than globalisation driven by higher commodity prices. Yet history has demonstrated that trade liberalization leads sooner or later to the transfer of manufacturing capacity from high to low income countries, wiping out entire swathes of jobs in said high income countries. So the argument that globalization driven by trade liberalization benefits workers in rich countries is shaky at best and demonstrably false at worst…

So much understanding of “what’s wrong” (from the mopes’ standpoint, of course) and so little in the way of prescriptions for “what is to be done” about conditions as described… Kind of like Tomgram, from the more military- and foreign-adventurism corner of the blogspace…

One might guess that we thinking people, with our perceptions and little debates about syntax and the elements of political economy and composition skills, are maybe just tolerated by the Blob, because we don’t pose much of a challenge to oligarchy and hegemony … And we vent off righteous steam that might get up too much of a head, and also reinforce, via our perceptions of the massiveness of “the problem,” the futility of resistance to something so yuuuuge, all interlocking directorates and self-licking incentives… Small mice can sometimes avoid being crushed by the elephants’ feet, if they are quick and inoffensive.

One wonders where the notion that elephants fear mice, a stock item in comedy, came from…

I never heard an economist say that all parties benefit from trade. Only that the TOTAL is greater. There is also no guarantee that both countries are better off. Politicians think on a one-dimensional “good-bad” axis.

We export jobs and get lower prices in return. Is it a good trade?

We have not enjoyed “lower prices.” Prices have been climbing, unabated, for decades. The alleged “savings” that should have been passed along to consumers, thanks to those lower labor costs, was instead captured as increased profits.

Lower household incomes, higher prices for goods, massive increases in debt to cover the difference.

The math isn’t difficult to explain the GFC of 2008.

…Prices have been climbing, unabated, for decades…

Not true for all products. The new car CPI has not budged since 1995 and that is due to both outsourcing and automation.

Wolf Street is covering this in depth. They tried higher prices, but so few people could pay them. Deep, deep incentives have kept sales from getting even worse than they are, probably.

Thanks – will check Wolf Street.

When Alibaba starts eating the retail lunch in the US, you’ll hear more squeaking from the elite class. After all, the idea is for the US to be top of the global supply chain, where the rest of the global supply chain is outsourced to other countries. The idea isn’t for that global supply chain to usurp the top tier.

Case in point. I was finding rimless frames that are of excellent quality on Alibaba for $15. Something comparable in US would be priced $200 and above. Seems like some creative destruction is about to be unleashed on the last-mile of retail optometry in the US.

It’s already unleashed. Try Zennioptical.com – prescription bifocals for $26.

China is gobbling up every corner of manufacturing and private equity is gobbling up every corner of service.

Daniel Gros does a great job investigating why the hollow shell of globalization has expanded through increased commodity prices, but the increase in commodity prices has been driven by the successive waves of quantitative easing programs launched first by the Federal Reserve, and now the ECB. Rising commodity prices has created what I call “synthetic inflation,” that is, inflation not backed by real demand but by speculation.

This has not only impacted stagnated/declining household incomes by increasing the prices of goods, but has also effectively removed even more monetary circulation at the mid levels of the economy, thus assuring another severe downturn in the future. The only question remains is, how long can the central bankers remain standing with their fingers plugging the holes in the dike.

The initial wave of commodity speculation, in the aftermath of the GFC of 2008, was pursued in large part by Wall Street banks setting up commodity trading desks. This became nothing more than another bank bailout, but operating under the radar. The “bailout” moved directly from households to Wall Street banks’ commodity desks, and thus profits enhanced and capitalization increased, by paying more than normal for goods. The normal pattern of price behavior in the immediate aftermath of a global recession (depression) should have been for prices to decline, or deflation. Instead, we witnessed price inflation during a massive economic recession.

See the white paper, “Synthetic Inflation” on Google Drive for more details: bit.ly/1KHjBKy

This all started in 1971 when Nixon took us off the gold inter-exchange standard. http://www.econdataus.com/tradeall.html

Up til then, trade (freer or less free) meant balanced trade (more or less). After then, it went downhill.

Thought experiment. Follow the money (currency). We send our currency to a foreign country or goods or commodities/oil and only a subset of it comes back in kind. What happens to the rest of our currency?

– imbalance started with KSA and oil

– continued with Japan, but we weren’t sending our jobs to Japan

– went on steroids when US corporations started figuring out that they could exploit these currency pegs by outsourcing supply chains to Mexico and China.

When somebody is going to bat for “globalization”, what they’re really fighting for is the global supply chain. They don’t want that to be unwound. Too disruptive don’t you know.

The lower prices in retail products was more than washed away by much higher costs in housing, medical insurance, car insurance, house insurance . The much higher inflation from those areas accounts for shrinking incomes relative to inflation since the 70s. High levels of immigration and wage competition with very low wage countries seems to accounts for US wages that don’t keep up with real inflation. Lets not forget Greenspan’s inflation numbers somehow missed the 2005-2008 housing bubble, even though housing is a huge part of wealth and expenses for the general population.