By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She now spends much of her time in Asia and is currently researching a book about textile artisans. She also writes regularly about legal, political economy, and regulatory topics for various consulting clients and publications, as well as scribbles occasional travel pieces for The National.

As more and more devices require software to operate, copyright holders employ a number of measures that thwart an end user’s right to repair a product s/he ostensibly owns.

As the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) recognizes, although in theory one may own a device outright, one’s only allowed to license the software necessary to make the device work properly. The terms of that license may preclude any efforts to tinker with the device, reverse engineer it, or have a third party undertake a repair.

To elaborate (according to the EFF):

Further complication: the software may come with digital locks (aka Digital Rights Management [DRM] or Technical Protection Measures [TPMs]) supposedly designed to prevent unauthorized copying. And breaking those locks, even to do something simple and otherwise legal like tinkering with or fixing your own devices, means breaking the law, thanks to Section 1201 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).

The United States Copyright Office on 22nd June released a report analyzing in great detail just these controversial Section 1201 provisions.

A Boing Boing article, US Copyright Office recommends sweeping, welcome changes to America’s DRM laws, spells out the DMCA’s broad sweep:

DMCA 1201 says that bypassing a computer program that controls access to a copyrighted work is a potential felony, punishable by a five-year prison sentence and a $500,000 fine (for a first offense!). This has allowed entertainment companies to take away many of the public’s rights under copyright — for example, by locking your ebooks to your account and your ebook reader, so you can’t lend or sell your used books when you’re done with them.

But DMCA 1201 goes much farther than this: because any “smart” device has software in it, and because that software is copyrighted, device manufacturers have used [DRMs] and DMCA 1201 to control who can diagnose and repair your gadgets (from phones to cars and beyond), and also who can make parts for them, who can make or remanufacture their consumables (from coffee-pods to inkjet cartridges), and how you can use them.

Pending State Measures

Many companies have taken full advantage of Section 1201 and other provisions to insert software that prevents consumers from using third parties to repair products they’ve purchased. About a dozen US states– including Massachusetts and New York– are mulling state legislation that would create a right to repair within their jurisdiction (see Waste Not, Want Not: Right to Repair Laws on Agenda in Some States. Unsurprisingly, some companies such as Apple and Samsung– which has heavily invested in limitation strategies– and vehicle manufacturers such as Ford and John Deere– are fiercely resisting such initiatives (see Apple Spends Big to Thwart Right to Repair in New York and Elsewhere.)

Additionally, a recent landmark US Supreme Court decision, Impression Products v Lexmark International struck down restrictions a patent holder sought to place on subsequent use of its products after their sale also has implications for the right to repair movement (see the further discussion in this post, Supreme Court Lexmark Patent Decision A Win for State Right to Repair Legislation.)

Copyright Office Recommendations

Section 1201 allows for some permanent exemptions from its provisions, for certain activities of libraries, archives, and educational institutions, law enforcement activities, reverse engineering, encryption research, and security testing.” (report, p. i).

In addition, it also permits the Copyright Office to grant exemptions that allow limited exemptions from its provisions. These exemptions are subject to renewal every three years, industry by industry, according to formal rule-making procedures (The Report goes into an excruciating review of these at pp. 20-29.)

The result: “This has led to a patchwork set of exemptions where modifications and repairs of some types of technology are allowed, but others aren’t,”, according to this report in The Hill, Copyright Office voices support for giving consumers the ‘right to repair’:

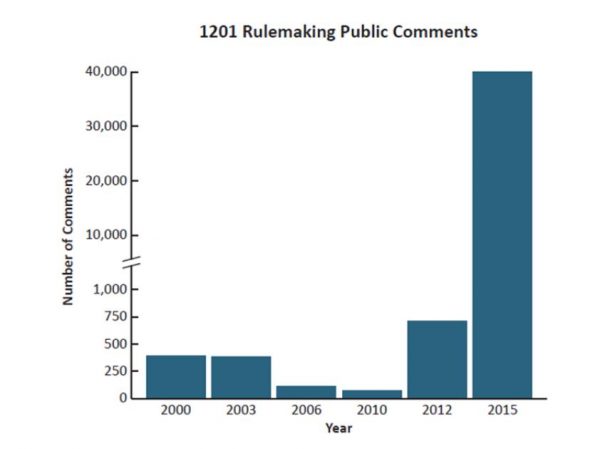

Consumers have increasingly criticized the Section 1201 restrictions. The first of six sets of rulemakings on limited exemptions were conducted in 1999, and attracted 392 comments. By 2015, this figure had skyrocketed to 40,000 in 2015.

Source: U.S. Copyright Office, Section 1201 of Title 17, p. 25.

With the surge in public interest has come an increase in permitted exemptions. According to the Copyright Office Report:

In the first rulemaking, the Office recommended only two exemptions, for lists of websites blocked by filtering software applications, and literary works (including computer programs) protected by [TPMs] that fail to permit access due to malfunction, damage, or obsoleteness.144 In contrast, the most recent rulemaking yielded a set of exemptions covering 22 types of uses, ranging from use of motion pictures for educational, documentary, and noncommercial purposes and jailbreaking and unlocking smartphones, tablets, and other devices, to accessing computer programs controlling motorized land vehicles for purposes of diagnosis, repair, and modification and accessing computer programs operating medical devices for purposes of security research (Report, pp. 25-26, citations omitted).

As Motherboard reports in The US Government Wants to Permanently Legalize the Right to Repair, the volume of public complaints has certainly provoked some pushback from the Copyright Office:

Thursday, the US Copyright Office said it’s tired of having to deal with the same issues every three years; it should be legal to repair the things you buy—everything you buy—forever.

“The growing demand for relief under section 1201 has coincided with a general understanding that bona fide repair and maintenance activities are typically noninfringing,” the report stated. “Repair activities are often protected from infringement claims by multiple copyright law provisions.”

Rationale for Copyright Office Position

My reading of the Copyright Office’s Report suggests that policymakers are indeed fed up with having to revisit the same sets of issues every three years. To the extent that any policy change makes it easier for consumers to have greater control over things they’ve purchased– to make it easier to get repairs done, for example, or to to eliminate situations “in which manufacturers of products such as garage door openers and printer toner cartridges have invoked section 1201 to prevent competitors from marketing compatible products, including replacement parts, because of the TPM‐protected software in those products” (Report, pp. ii-iii) — I’m all for it.

But I noticed that another rationale for relaxing Section 1201 had also crept into the analysis– one I’m definitely not on board with:

These challenges will only become more commonplace, these users argue, as the Internet of Things expands and growing numbers of everyday products—automobiles, refrigerators, medical devices, and so on—operate using software protected by TPMs. While consumers historically have been free to repair, modify, or tinker with their own goods without implicating copyright, such activities now may require circumvention of a TPM to access the software that enables the device to function. For many, it is not clear why copyright law should apply at all in these contexts (Repor,t p. iii).

Real Problem, Weak Response

The Copyright Office report identifies a real problem– Section 1201 has been stretched far beyond what Congress (ostensibly) claimed to be its scope. Many secondary accounts of last week’s report zero in on this language:

The growing demand for relief under section 1201 has coincided with a general understanding that bona fide repair and maintenance activities are typically noninfringing. (Report, p. 90)

The Report then continues:

As described in detail below, to the extent section 1201 precludes diagnosis, repair, and maintenance activities otherwise permissible under title 17, the Office finds that a limited and properly‐tailored permanent exemption for those purposes, including circumventing obsolete access controls for continued functioning of a device, would be consistent with the statute’s overall policy goals (Report, p. 90).

I have no quibble with that position.

Where I think the report falls short is in the incrementalist remedies it proposes: mere tweaks to the existing rule-making framework, while leaving the DMCA largely intact. The paragraph cited immediately above continues– and shies away from endorsing anything but the most limited right to repair:

The Office does not, however, recommend that such a permanent exemption extend to circumvention for purposes of making other lawful modifications to software, or “tinkering.” Instead, the Office recommends that these activities continue to be addressed through the rulemaking process, which is able to tailor exemptions to specific classes of works, based on the evidentiary record (Report, p. 90).

See also this further discussion:

Copyright owners strongly opposed an exemption for “tinkering” on the ground that it would be vague and overbroad….

These concerns of copyright owners are valid, and the comments received in response to this study suggest that tinkering is hard to define, and that there is no accepted meaning or limitations on what it involves. To be sure, in many cases modification activities may not implicate significant copyright interests. On the other hand, some tinkering activities may result in the creations of new works in ways that implicate the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works. Commenters have suggested no reliable way to define with any precision a category of lawful adaptations, generally, for purposes of section 1201. Accordingly, in contrast to diagnosis, repair, and maintenance, the Office cannot say that lawful modification of software is categorically unlikely to result in harm to the legitimate interests of copyright owners.

The Office therefore concludes that such activity does not provide an appropriate basis for a permanent exemption at this time. The triennial rulemaking process, however, will continue to provide a means to obtain exemptions for these uses, and the Office is hopeful that the streamlining changes outlined below will lessen the burden of renewing exemptions found to satisfy the statutory requirements. Moreover, as described above, the Office believes that section 1201(f) should be available to accommodate many concerns related to software interoperability. Collectively, these exemptions may cover a substantial portion of circumvention activities involving software‐enabled products in which there is a legitimate consumer interest. (Report, pp. 96-97, citations omitted).

And there is much more similar material, in a similar vein, especially in the latter part of the Report (Report, pp. 132-147).

I here spare readers more extended analysis of this legalese– all 152 pages of it, sans appendices. And I instead turn to this short piece, in The Register UK, US Copyright Office suggests ‘right to repair’ laws a good idea— which despite its chirpy headline, admirably does:

Further: “virtually all agree that section 1201 was not intended to facilitate manufacturers’ use of TPMs to facilitate product tying or to achieve a lock‐in effect under which consumers are effectively limited to repair services offered by the manufacturer”. [Jerri-Lynn here: The netted quotation is from the Report.]

Sorry, tinkerers, you’re not included: the shift in policy is specific to repair (and recovering kit that’s obsolete, that is, unsupported by the manufacturer anyhow). If you want to circumvent TPMs to modify a product, you’ll have to go through Copyright Office rulemaking processes.

Indeed, the report specifically disdains a more sweeping overhaul of the DMCA framework– and more generally, copyright law. Indeed, the Copyright Office concludes that the existing system works well:

The past twenty years have witnessed the rise of an array of new platforms and formats for delivering creative works to the public, and in this respect, section 1201 has succeeded in fostering a thriving, innovative, and flexible digital marketplace, as Congress envisioned. The basic framework of section 1201—including its treatment of circumvention as a standalone violation independent of copyright infringement and robust anti‐trafficking provisions—remains sound, and the Copyright Office does not recommend broad changes to the statute’s overall scope. Within this existing framework, however, it may be appropriate to recalibrate provisions in section 1201 to better reflect changes in technology since the DMCA’s enactment nearly two decades ago (Report, p. 150).

Now, call me cynical, but haven’t we seen too many similar pages from this master playbook before– a rhetorical flourish, followed by a tepid or otherwise inadequate statutory or regulatory response?

Alas, with bots the number of rulemaking comments isn’t an indicator of much any more.

It would be nice if government comment sites were to use something like Captcha. It’s annoying, but it would eliminate a lot of fake comments. When I commented on net neutrality, I don’t remember anything like that.

Of course, it would cost money to modify the government web sites, and the Congress is unlikely to appropriate the funds, no matter how useful this would be.

It doesn’t cost too much, apparently, to build a separate API for mass comment submissions in advance of the net neutrality submission period. I freely speculate that Comcast asked for it.

Parts of the US of A are already starting to look like Cuba – with ancient vehicles kept in running order by repair and rebuilding by the owners and shade tree mechanics. I have a perfectly usable 1989 F250 which I mostly maintain myself with some help – recently replaced the solenoid, starter, and alternator with quality replacement parts – alternator made in Mexico by Magneto Marielli, owned by Fiat-Chrysler (!). I can keep it running indefinitely – it’s easy to maintain, parts are cheap, and every mechanic in every little town knows how to fix it.

The more greedy and predatory the monopoly capitalists get, the more regular people get creative and make their own solutions. Why buy a new truck for $40k, especially if you have to pay their dealers’ extortionate rates to repair and maintain it? It’s sort of like why vote Democrat when their leadership is in bed with monopoly capital?

I have a friend who is doing the same thing with bicycles. She is a whiz at restoring and repairing 1970s vintage bikes.

Newer bicycles have become so full of complicated, proprietary tech (some are battery-assisted), that owners have difficulties performing simple repairs that were possible once. 1970-era bikes are not subject to that disease.

But, but consumers have to be forced to buy new vehicles because of jawbs. Clearly in this instance the logic of capitalism and the logic of thrift and environmentalism are at odds. Most vehicles from the late 80s onwards meet current pollution and mileage standards (in part because those haven’t been advanced). Making a new vehicle to replace them just creates more carbon so from an environmental pov we should all be letting our vehicles age.

And with cars in particular there are safety concerns when manufacturers use proprietary software. All of the code that controls how the vehicle operates should be open source. This would mean that some owners would be tinkering with their cars in ways that may affect safety and manufacturer liability but owners have always done that anyway and are doing it now through hacks available on the “darknet.”

This is a point that will get endless fodder for jurists: what is the difference between “tinkering” and “repairing” when it comes to software?

The major point is that software is functionality, and that one must alter it in order to perform the following functions:

a) correcting a malfunction (error, popularly “bug”);

b) upgrading it to comply with new regulations;

c) resetting it in case the underlying hardware changed.

Unfortunately, very often, manufacturers cease to provide firmware or software updates pretty soon after releasing a product. This is already the case with items such as mobile phones and routers, and will become a permanent headache if the IoT actually catches on.

How the Copyright Office and the Congress define tinkering vs. repairing in the context of software will determine whether a “right to repair” effectively exists or not. Once again: repairing anything involving software may imply modifying software, i.e. overriding copyright.

I’m doing the same with my 170,000 mile Dodge Ram. I plan on it being my last vehicle (I’m old enough I can make plans like that). I just put in a new air conditioning compressor, condenser, accumulator and expansion valve. Other than an evacuation which a local shop did for free to get the Freon, I did the whole job myself. I’ve always been intimidated by AC work but with a bit of reading it was fairly easy.

Most of the time, the commenters at this site appear to be missing whatever the major point is — and this time is no exception.

The point is the endgame of offshoring jobs, industries and technologies is the “no repair” law and similar strategies.

That is and was the point . . .

+1. I keep my old car for the same reasons.

adding: the past couple of years have seen a slump in new tractor and combines sales, for whatever reason. However, older tractors and combines not subject to DRM restrictions (not the same controlling software) are seeing steady sales and rising prices, for whatever reason.

A friend of mine with some new tiny car had a sensor go awry recently. this caused the car to automatically reduce maximum speed to something like 20 mph while on the traffic jammed freeway. She was lucky she wasn’t run over by a hundred other cars and trucks. It took several mechanics (dealership couldn’t figure it out) to figure out the problem was the sensor itself. She had to drive around for a week at less than 30 mph max in an otherwise perfectly running car.

Reliance upon backup cameras has now given car makers carte blanche to design cars with enormous blind spots. Recently, moved an friends SUV, couldn’t see a thing backing up without the cams and of course all the screens and software. Very dangerous.

Count me in as one who would rather spend forty k (ha!) keeping my old jeep and tacoma in running order. Total second hand (to me) cost for both vehicles, less than 9k.

On the other hand the computer that controls your engine means a 20 year old car can run as well as it did the day you bought it. Implementing modern pollution controls in an old style carbureted engine is a maintenance nightmare. Most of the digital technology added to cars has been a good thing including, IMO, backup cameras.

Which is all the more reason that digital right to repair laws should be supported.

when the grid goes down none of the computers in newer vehicles will work..

65mph on the 5.. it’s just us oldies..

SOLUTION: Make sure your laptop or desktop device comes with a software license (usually free) that allows you to use and repair it at your option; hundreds (possibly thousands) do.

Then if you have problems, and can’t do it yourself, your friendly local computer guy or gal can help you for a very small sum.

MORAL: Break the “Billy Boy:” , “Apple Jack”, etc. habit!

Where can I find a list of laptops and desktops that support use and repair at my option?

Wait a minute. I think I’ve found a US-based desktop and laptop builder and fixer. Link:

https://www.pugetsystems.com/

Note to all of the photographers out there, this company is highly recommended by members of the Photo.net community.

https://www.rethink-it.org/

‘Section 1201 has succeeded in fostering a thriving, innovative, and flexible digital marketplace, as Congress envisioned.‘

‘Congress envisioned’ … mwa ha ha ha, that’s hilarious. Like claiming that ‘Farmer Brown surveyed his back forty, rich and fertile as the earthworms had envisioned.’

When gov goes feral fencing off our culture with overbroad copyright, torrents and VPN are our friends.

Smash DMCA.

Ah yes, the DMCA, known with some distinction as the worst copyright law ever written (after the Berne Convention and its “you don’t need to register your copyrights” provision). Thanks to the DMCA, two generations now have grown up thinking copyright is not only a bad joke but something to be actively subverted.

I note that my fancy-schmancy Sony teevee will only allow its firmware to be updated from a Sony-branded USB stick. That is beyond petty.

A Carrington-Level Solar Incident would be just the thing to shake the hubris out of Homo modernus var. ‘Idiocrenesis’….