Yves here. So having economists try to create groaf is less important to growth than commonsensical things like staying out of war, avoiding pestilence if you can, and preventing financial crises.

By Stephen Broadberry, Professor of Economic History, Oxford University and John Joseph Wallis, Professor in the Department of Economics, University of Maryland. Originally published at VoxEU

Most analysis of long-run economic performance abstracts from short-run fluctuations and seeks to explain improved performance through an increase in the rate of growth. Using data on annual rates of change of per capita income reaching back to the 13th century for some countries, this column show that improved long-run performance has actually occurred primarily through a decline in the rate and frequency of shrinking. Structural change, technological change, demographic change and the changing incidence of warfare offer at best a partial explanation; a full understanding requires a consideration of institutional change.

To date, most work on long-run economic performance has focused on ‘growing’, but recent work for the post-1950 period has suggested that economies vary as least as much in how they ‘shrink’ as in how they grow (Easterly et al. 1993). However, despite these findings on the volatility of GDP per capita in poor countries, there has been little research into why poor societies shrink so often or by so much. Furthermore, economic historians have not systematically investigated the possibility that improved long-run economic performance since the 18th century could have been due to less shrinking rather than faster growing, despite the widespread acceptance of the idea that living standards improved slowly by modern standards during the Industrial Revolution. In new research, we show that to understand economic performance over the long run, economic historians, growth economists, and development specialists need to explain a reduction in the rate and frequency of shrinking rather than an increase in the rate of growing (Broadberry and Wallis 2017).

Empirical Evidence on the Importance of Shrinking

Economic performance over time is the aggregation of short-run changes measured at the annual level. We make use of an identity to decompose long-run economic performance into the contributions of growing and shrinking. The contribution of growing is the frequency with which an economy grows multiplied by the (positive) rate at which it grows when growing (the growing rate). The contribution of shrinking is the frequency with which an economy shrinks multiplied by the (negative) rate at which it grows when shrinking (the shrinking rate). In three data sets covering the period from the 13th century to the present, we show that better long-run economic performance has generally occurred not so much because of an increase in the rate of growing, but more because of a decrease in the frequency and rate of shrinking.

<>Economic Performance Since 1950

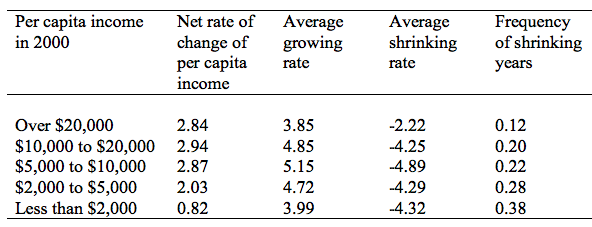

Table 1, derived from the Penn World Table, sets out information on the performance of 141 countries over the period 1950-2011, broken down by level of income. The first column shows that the economies with per capita incomes above $5,000 in 2011 all saw similar net rates of change of per capita income over this period, while the poorer economies, particularly those with incomes below $2,000, saw much lower net rates of change. However, we can see from the second column that this was not because they grew slowly when growing. Indeed, the average growing rate for the poorest economies was actually higher than for the richest economies. What made the difference was the rate and frequency of shrinking: the average shrinking rate was much higher in the poorer economies than in the richest, while the frequency of shrinking was much greater in the poorest economies.

Table 1 Penn World Table 8.0: Growing and shrinking, 1950-2011

Source: Derived from Penn World Table 8.0, http://www.rug.nl/research/ggdc/data/pwt/pwt-8.0.

Economic Performance in the 19th and 20th Centuries

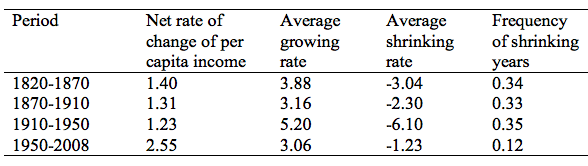

A similar analysis can be conducted for 14 European and 4 New World economies, derived from the Maddison (2010) database, and covering the period 1820-2008, broken down into four sub-periods. The first column of Table 2 shows that the annual net rate of change of per capita income increased from 1.40% during 1820-1870 to 2.55% during 1950-2008. Perhaps surprisingly at first sight, the second column shows that this was not caused by an increase in the average growing rate, which actually fell from 3.88% during 1820-1870 to 3.06% during 1950-2008. The reason for the improved economic performance can be seen in the third and fourth columns: a substantial fall in the average shrinking rate from -3.04% to -1.23%, combined with a fall in the frequency of shrinking from 34% of years to just 12%.

Table 2 Average rate of change of per capita income in all years, growing years and shrinking years, 18 European and New World countries, 1820-2008

Source: Derived from Angus Maddison (2010). “Statistics on World Population, GDP and Per Capita GDP, 1-2008 AD”, http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm.

Economic Performance Back to the 13th Century

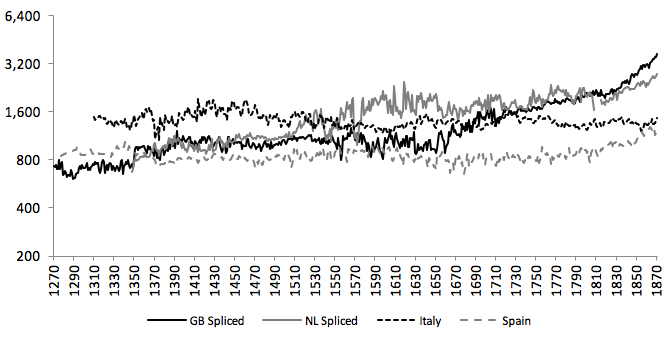

Figure 1 plots the annual time series of per capita GDP for four European economies over the period 1270-1870. For Italy and Spain, there was a clear alternation of periods of positive and negative trend growth over periods of a decade or more, with growth booms typically followed by growth reversals, leaving little or no progress in the level of per capita incomes over the long run. Per capita GDP therefore fluctuated without a long-run trend before the mid-19th century. For the cases of Britain and the Netherlands, although there were alternating periods of positive and negative growth until the 18th century, there was also a clear upward trend over the long run, with the gains following the Black Death being retained, and the growth reversals eventually disappearing with the transition to modern economic growth in the eighteenth century. As periods of negative growth became less frequent and as the rate of shrinking decreased in northwestern Europe, Britain and Holland overtook Italy and Spain.

Figure 1 Real GDP per capita in Britain, the Netherlands, Italy, and Spain, 1270-1870 (1990 international dollars, log scale)

Sources: Broadberry et al. (2015); van Zanden and van Leeuwen (2012); Malanima (2011); Álvarez-Nogal and Prados de la Escosura (2012).

Decomposing long-run economic performance into the contributions of growing and shrinking in this long-run data set yields similar results to those obtained in Tables 1 and 2. The improvement of long-run economic performance in Britain and the Netherlands, as they overtook Italy and Spain and made the transition to modern economic growth, occurred despite a reduction in the average growing rate. The improved performance was the result of reductions in both the frequency and the average rate of shrinking.

Explaining Why Some Economies Shrink More

These empirical results suggest two social patterns. One pattern is societies with high growing rates, high shrinking rates, and high shrinking frequencies, resulting in less, little, or no growth over the long term. This pattern has dominated human history for the last 10,000 years. The other pattern is societies with low growing rates, low shrinking rates, and low shrinking frequencies, resulting in slow but steady growth over the long term. This second pattern appeared only after 1700, and then only in a handful of societies.

Historically it is too soon to tell whether the low growing, low shrinking, positive growth long-term pattern will persist. But the high growing, high shrinking, little or no long-term growth has persisted for at least as long as we have data. There is little doubt that the pattern has repeated itself with variations through time. The obvious question is: can we find corollary patterns in the historical record?

We consider four possible proximate factors: (1) structural change from an agricultural sector dependent on the vicissitudes of the weather to a more stable service sector; (2) technological change, transforming downturns from an absolute decline in output to a slower rate of positive growth; (3) demographic change with fertility control leading to the avoidance of over-population and diminishing returns; and (4) the changing incidence of warfare, with a more peaceful environment reducing disruption to trade and output. But taken together, these proximate factors do not provide a full explanation, since factors such as structural change, technological progress, and demographic transition are themselves usually seen as part of the process of development rather than ultimate causes such as institutional change.

We know that in a crude correlation sense, the institutional structure of societies in the high growing, high shrinking pattern differs predictably from the institutions in the low growing, low shrinking pattern. For obvious reasons, efforts to understand the relationships between institutions and growth have focused on the effects of institutions on the productivity of the economy. In general, more secure property rights, the rule of law and clear unbiased enforcement of commercial contracts, a modicum of civil liberties, and personal security clearly contribute to economic productivity through investments in physical and human capital, and through the size and scope of markets. However, if these institutional structures produce such good economic outcomes, it is important to ask why all societies do not possess them.

North Wallis and Weingast (2009) analysed how societies create and sustain social order, with important implications for the nature of rules. In a world where violence is endemic, powerful individuals and organisations have an incentive to enhance social order. To reach credible agreements to limit violence, powerful actors have to believe that other powerful actors will honour commitments not to use violence. Coalitions of powerful organisations manipulate economic privileges to create rents. To the extent that those rents are adversely affected by violence, powerful individuals and organisations have a credible incentive to honour their agreements not to use violence. Those agreements operate within narrow ranges of circumstances, of course. Outside of those ranges, agreements break down and economies shrink. North Wallis and Weingast call this the logic of the “natural state.”

The nature of the agreements between powerful actors that support social order in a natural state paradoxically makes it very difficult, if not impossible, for those powerful actors to commit to rules that treat everyone the same. The rules have to recognise the privileges of powerful elites, and one of these privileges is that the rules apply differently to elites, and differently to different elites. The rules that emerge in a natural state, therefore, are ‘identity rules’ whose form and enforcement differ according to the organisational identity of the individuals.

These features of identity are not flaws in the institutional structure of natural states, rather they are an inherent part of how these societies work. While identity rules may persist, they are essentially a solution to short-run problems that exacerbate long-run instability. Identity rules treat different elites differently, and therefore as elite identities change over time, how the rules apply will differ among elites. When circumstances change sufficiently, existing institutional agreements cannot solve the problem of intra-elite coordination. The result is disorder and violence, which leads in turn to shrinking. The process is much more complicated and nuanced, but the key point is that identity rules promote short-run solutions to elite conflict, yet result in long run instability.

The ‘good’ institutional rules in the developed world are enforced impersonally, i.e. they apply equally to all citizens (ideally). Impersonal enforcement of these rules means that elite agreements based on the availability of the rules do not depend on identity and the arrangements are inherently less fragile. The incentives for higher investment and effort provided by these institutional rules are an important source of growth. However, it appears from the quantitative historical record that the effect of these institutional rules on fragility and the proclivity for shrinking matters more than their direct effects on productivity.

Please see original post for references

This also sounds Minsky. Good times lead to bad. Conflicts arise among the elite of various societies and the “intra” elite resort to violence; supporting economies are damaged and “shrink” and it takes much longer to repair the damage and achieve the same level of prosperity as before. Because in the “shrinking” some beneficial aspects of the former economy are destroyed forever, etc. Hard to believe there are any “statistics” that are useful before the industrial revolution. But Minsky could have discovered a universal law of human behavior. This raises the next question: How do we control it?

Relating this to the China post below, the long term Chinese history (very long term, over millennia) has been one of periods of extraordinary growth and expansion, with infrequent, but regular catastrophic retreats, either through invasion or from internal decay.

I can’t recall the writer, but years back I read a book on economic history that theorised that one reason for Europes ultimate trumph up to the mid-20th Century was that geography broke it up into permanent smaller States that were close enough to allow a free exchange of ideas and people, but far enough away, and with enough physical barriers, that when one nation collapsed, others provided a refuge for human capital.

The result was that catastrophic wars or bad decisions by leaders only led to localised reversals, there was always a stable nation or mini-empire somewhere to keep knowledge and development moving forward. In contrast, areas like China or the Middle East tended to have very centralised governments and empires as a result of geography, leading to more intense failures when the systems broke down as centuries of know-how gets destroyed.

The ‘geography is destiny’ theory sounds like jared diamond’s idea developed in guns, germs, and steel. He’s more nuanced than that, but he’s onto something.

On the other hand, i had to rewire my understanding of history somewhat after reading charles mann’s 1491 (after lambert plugged it). Charles mann pointed out that things were much more complex and the history of european conquest was more about germs and a little dumb luck and less about superior technology of europeans.

Yes, its similar to Diamonds theory, and I think he argued the same thing, just in a different manner. While I think the primary reason why some countries recover rapidly from reversals and others don’t comes down to political/social structures, often these are driven by geography. A nation that is a wide flat plain with one big river that floods a lot is always going to develop a different sort of political-social system than one which is lots of fertile valleys divided by high rocky passes.

The hypothetical you just outlined reminds me of a couple of lectures from toby hemenway. He pointed out the differences between mountain people (often semi-hunter gatherers and fiercely independent) and the type of civilizations that would spring up in lowlands (often using intensive agriculture of annual staple crops).

I don’t have any links right now on my crappy phone but they’re easy to check out on youtube. Very enjoyable and worth your time.

Maybe an “improvement” is already in the works, leading to the “UNTIED States…

Sure seems like what the Kochs and others are working at, the destruction of that institutional memory and such competence as there has been, stored up in the administrative State, is one salient form that characterizes a “shrinkage.”

Anyone else sickened by the idiotic postulates, those notions of “growth” and “trade” and stuff, that form the “de-base” of all these economologistical suppurations? And of course these get repetition and reinforcement from all the quarters that have the power to matter. IBG-YVG, “I got mine, and I’ll get yours too pretty soon.”

Yah, in the long run we are all dead. But there are various ways to get to that condition, of various degrees of pain and horror.

OTOH, the central premise of this post seems to me entirely correct – that long term growth is essentially the minimization of decline.

OTO, the last three paragraphs seem much more speculative, not obviously connected to the rest of the post. I went to the original post to see if there were references I was missing but none in that post either. Those paragraphs are entirely consistent with Mirowski-ish neoliberalism, in which one of the core claims is that neoliberal control of the state includes the right of neoliberal (corporate) elites to use the “governing exception” in their own interests. (Roughly: “Government is bad but in exceptional circumstance we need exceptional government action to ‘preserve’ the market system.”) So I am sympathetic.

But I am also skeptical of economists when they go from data analysis to ad hoc speculation. The institutional rules they suggest earlier in the piece that support long-term growth (In general, more secure property rights, the rule of law and clear unbiased enforcement of commercial contracts, a modicum of civil liberties, and personal security) don’t seem to meet the criteria they identify as problematic at the end of the piece. Perhaps the authors are making a “countervailing powers” argument – you need countervailing powers to ensure that a single faction doesn’t manipulate the rules to benefit only themselves? But it is hard to make this argument for the period before WW2, much less the last 1000 years.

I suspect that all is revealed in “North Wallis and Weingast (2009)”. Seems like that’s what the authors of this essay are citing as evidence that rules agreed to by enough elites are a guarantee of stability.

Re: last 3 paragraphs: take a closer look. I’m pretty certain that the original post is stating how in most societies (being “natural states”), the elites’ balance-of-power arrangements work well for a time but are fragile and prone to break down, leading to difficult declines. But in societies with well-established rule of law “the arrangements are inherently less fragile”, so declines are less frequent. A key difference is whether the rules apply equally to all, or differently based on elite identity.

Or, as Robert Anton Wilson put it

There’s a subtle bit of misdirection going on in the first quotation. “In a world where violence is endemic” lacks agency and implies that all violence is somehow equal. Some people use violence in order to manipulate and control others for their own benefit. Other people use violence in an attempt to escape such control. These are not equivalent. Success by the former type of people conveys upon them social power — and these powerful-because-violent people then make agreements between themselves whenever it seems likely they’ll be able to extract more wealth through truce than through invading each other’s “territories.”

Again, against each other. The type of violence that these violent elites carry out against the populations they extract rents from, and which allows them to extract those rents in the first place, is refered to as “manipulating economic privileges.” That euphemism covers up little things like mass killing and deportation of people so you can use the land they live on.

According to this analysis, the essential social problem is one of coordinating elite interests. That, we are told, is what will lead to peace and prosperity. We need the rule of law not because of any quaint notions like ethics or doing right by us little people — no, it’s because that will create a more long-term stable environment for the elites.

So, 1) elite power-sharing arrangements make equal treatment an impossibility; 2) these arrangements lead to instabilities that result in violence among elites; but 3) we can avoid that problem by somehow just instituting a whole new framework for coordination of elite interests.

At this point, I’ll just remind you that the US is one of those developed countries with the “‘good’ institutional rules” that “apply equally to all citizens (ideally).” How telling is it that the authors feel the need to hedge their statements with scare-quotes and parentheticals. So how’s about we not make absurdist arguments that ignore that societies, just like every other complex system, are path-dependent — i.e. history matters — and you can’t simply jump from one evolutionary state to some other state that is completely different just because you’ve decided it’s a good idea.

Our ‘good’ rules in Western, developed societies are simply the current phase of power-sharing arrangements among violent elites, that privilege some people over others, and the elites over everyone always. Do I need to mention the bank-bailouts? Do I need to mention the multiple police officers let off for murder? Suggesting we move to a system that treats everyone fairly is ahistorical.

Here’s a radical idea, how about we stop thinking or caring about GDP — which we all know is a BS measure for any type of social or individual welfare — and try not to think about social progress in terms of creating a more stable environment for the violent and unscrupulous members of our society who we call “elites” to continue extracting rents from us? Because the argument that is being made in this article, on the sly, is that we need to keep our oppressors contented to save ourselves from even worse oppression. At least that’s how I’m reading it.

…adding, that if we want long-term sustainability for ourselves, and something more valuable and more tangible than GDP to show for our efforts, we would do better to make ourselves ungovernable by elite rent-extracters than we would by pushing for a slightly more equitable application of the laws in the current situation.

Yes, let’s have a discussion about what effect the false invasion of Iraq has had upon the world since 2003. That should be a good place to start and the end would be the article Seeking Refuge In Refugees.

No one seems to pay for the violence they unleash on the world.

According to this analysis, the essential social problem is one of coordinating elite interests. That, we are told, is what will lead to peace and prosperity.

As a quasi-historical piece, I could forgive the authors for ignoring the premise, “Given existing distributions of wealth and power, the essential social problem …” Which I think is probably true.

My argument would be (see Marx, Polanyi, JK Galbraith, etc.) that the only way to broaden those social ‘rules’ to everyone is for working people to develop into a class willing to challenge elites and get new social rules written.

“We could stop caring about GDP” but I don’t think that would change anything. (Or perhaps, the essential change(s) would have already had to have happened for us to stop caring about GDP.) I would argue that elites have stolen the concept of well-being and substituted for it GDP. What they want is for “us” to ignore that theft, to piss and moan about how stupid their measures are (not at all accusing you of such) but not to challenge their ability to define for all of us what the appropriate measures are.

Just an opinion – once “working people…develop into a class willing to challenge elites”, exactly what new rules will be written? This is the dilemma of class struggle in a nutshell; if a class can do that much, it may as well TAKE OVER the writing of the rules, and not be content to just “challenge”. If you only challenge, then what comes about is a reaction from those who are challenged, and if media and political control is up for grabs, they who have the big money will win. Loss of influence by the working class will result, and loss that is painfully actual will ensue.

It’s nice to track the ins and outs of political one-ups-manship, but we have enough experience to know with certainty that we cannot win a rigged game unless a revolutionary situation both is a threat AND an actuality. I believe this is what you are getting to, without naming the beast.

Figure 1 shows an intriguing divergence betwen Britain and the Netherland between roughly 1540 and 1660. In this period Britain had erratic GDP/capita around a flat-lining to gently declining trend while the Netherlands had the mirror image but more pronounced. It seems like something was working to the disadvantage of Britain and to the advantage of the Netherlands which, because smaller, benefited more

It’s purely speculation but could this be due to Henry Vlll’s falling out with the continental powers over his wish to marry Anne Boleyn (“Brexit 1.0”), relations eventually repaired by the restoration of Charles ll in 1660?

It may have been less British decline than Dutch growth during that period. Exploitation of peat as a fuel was a major driver of the golden age for the Dutch. The tidal marshlands which made up much of the country was actually sphagnum moss, which when dried was an excellent fuel for making the Dutch Delftware which was a big export and one of the foundations for Dutch wealth at the time. But over extraction resulted in both depletion and extra flooding (the peat bogs were an excellent flood buffer). Lack of fuel and wood was a major constraint on Dutch growth going into the 18th Century.

They held labor while inflating rent for two generations. They can let the pendulum swing back or watch it blow up. For all ships to rise, a positive demographic slope, natural equilibrium, is required. When the slope went south, they replaced labor with debt, artificial intelligence, and artificial intelligence can only replace artificial intelligence. When they replaced rural policy with best urban practice, they created a financial short to runaway debt.

Watching something on TV or Youtube, or reading a book is one thing. Actual work is another. Socialism is simply employed as the cheapest possible dress for feudalism. Its all welfare.

DId you build that dynamic counterweight?

Didn’t Aesop tell this story with much less math? A tortoise, a hare, something-something slow and steady wins the race….

we are entering the malthusian age.

Malthusian age does not mean starving cannibals. Not till the end anyway.

Malthusianism means declining standards of living for the labour, and rising prices (scarcity) of resources. Resource management is another question altogether as intelligence is the only way to fight entropy.

One thing malthusianism will imply is increasing societal anger and decline of social order. (Brazilization)

Each generation is a clean slate. What will happen depends on the information and skills passed onto the next generation. For those who had duck and cover drills in grade school, the restart of the Cold War is traumatic. Mid-Age and younger, the fear is missing. Today the guiding western goal is enrichment at the expense of everyone else. Greed, denial and contempt is necessary to ascend to the top. The West is in a slow motion collapse as five men grab the other 50% of the world’s wealth. If there are any academic survivors of the forever wars and climate change in the 22nd century, they will be glorifying the wonder of the Chinese Greater Prosperity Globe.

Can we live in a globalized world that depends solely on “GDP” as a guide to progress?

Doesn’t take a genius to see that that concept leads to an abyss of humongous proportions. Unless AI, Tech or “other” can compensate for declining “natural resources” to exploit, fend off natural or human pushed climate changes starving so many of just clean water human kind will descend into that pit. “Elites” have always ruled somehow or someway throughout history. The common folk most always if not too repressed will follow the path of least resistance. Sadly, elitists never learn that to reach for “more” after having so much will lead eventually for the commons to seek their heads. Wars leading to societal (and physical) destruction is like the different sowing seasons of agriculture; you make a bet you can win the game but sometimes have to plow under the crop because there are no takers. Wars are supposed to “cleanse and purify” thru destruction; but, like infections they sometimes spread and kill the whole corpus. Given the natural tendencies of humankind ie greed, avarice, a murderous bent when “crossed”, modern racism, total destruction weapons available to outright crazy elitists and the end game of “kill them all and let God sort them out” sort of religions and beliefs, I have not the slightest belief of any long term redemption.

To return to earthly sanity one important change in the US (and as most actions by the US will have ripple effects globally) is to overthrow Citizens United. There are others such as a new cloak of rules for the “capitalist games” such as Glass-Steagal would give some hope and impetus for a vision of “change” to the commons. Relying solely on GDP as a measure of progress is self-defeating in the long run.