Yves here. This is a classic from Peter Dorman which we missed when originally published, so we are grateful to Angry Bear for featuring it.

By Peter Dorman, an economist and a professor at Evergreen State College whose writing and speaking focuses on carbon policy, child labor and the global financial crisis. Originally published at EconoSpeak

You would know this if you read your Cahuc, Carcillo and Zylberberg, but you probably won’t, so read this instead.

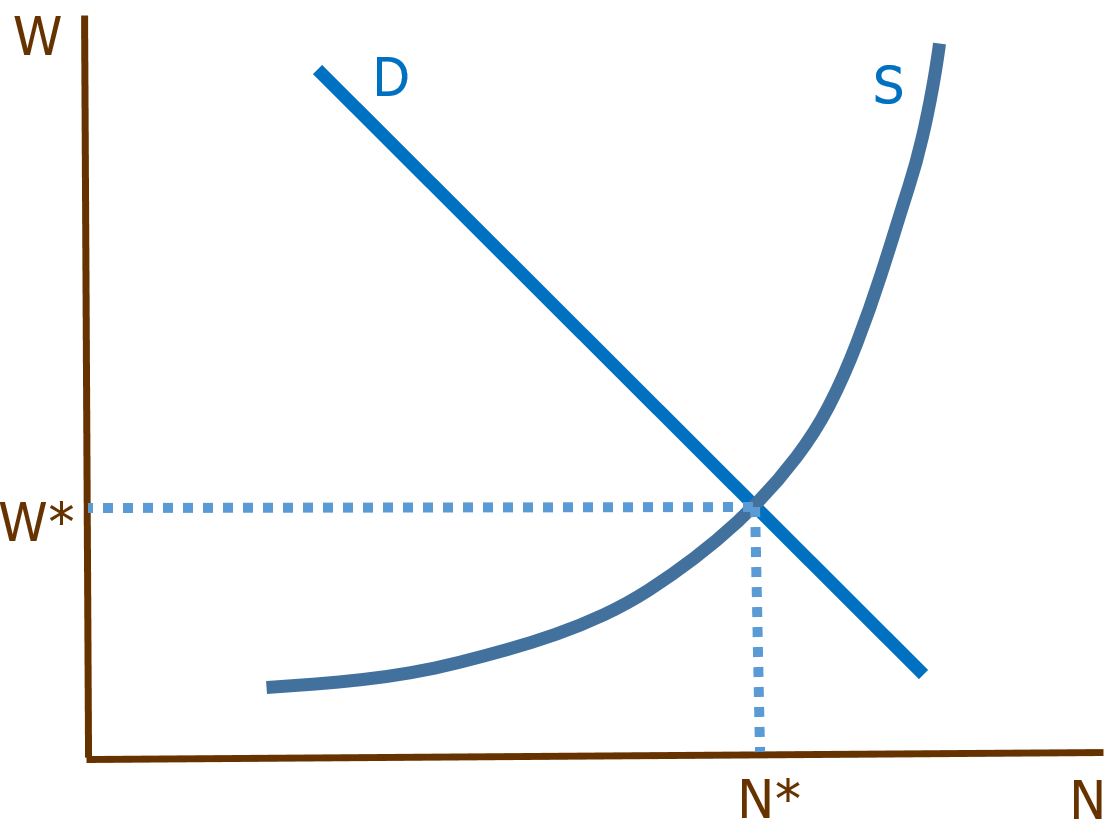

A standard S&D diagram for the labor market might look like this:

It’s common to use W (wage) on the price axis and N (number of workers) on the quantity axis. Equilibrium is supposed to occur at the W where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded. From here you might introduce statutory minimum wage laws, or jobs with different nonpecuniary benefits and costs, etc. The default conclusion is that free markets are best.

But hold on a moment. S and D don’t tell you how many workers actually have jobs or how many jobs are actually filled—these are offer curves. The S curve tells you how many workers would be willing to accept a job at various wages, and the D curve tells you how many jobs would be made available to them. That’s not the same as employment.

They would be the same in a world in which labor markets operated according to a two-sided instantaneous matching algorithm, something designed by Google with no human interference at any stage of the process. In such a world all offers would enter a digital hopper, and all deemed acceptable by someone else’s algorithm would be accepted immediately. Maybe not Google but Priceline.

But that’s not the world we live in. Finding out about job openings and job applicants is somewhat haphazard and time-consuming. Applicants and jobs differ from one another in lots of obscure, subtle but crucial ways. You really wouldn’t want an algorithm to make these decisions. And so only some workers who offer their labor, even at what might be an equilibrium wage rate, are taken on, and only some job openings workers willingly apply for are filled. When we measure unemployment and vacancies à la JOLTS, we are not seeing offers but changes in actual employment and disemployment.

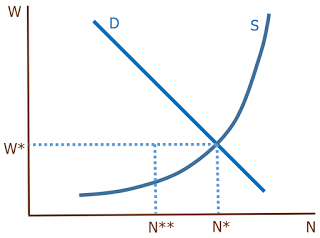

So let’s redraw that diagram.

To the left of N*, the equilibrium number of employment offers, we find N**, the number of workers whose offers have actually been accepted and are now on the job. A little reflection should be enough to indicate that S&D is a lousy way to frame this distinction.

First of all, what determines this gap between wanting to work (or fill a job) and actually working (or filling it)? What does this apparatus tell you about N*–N**? Nothing. It isn’t built to answer that question, and it doesn’t answer it.

But it’s worse. The apparatus indicates that N*–N** is the same on both sides of the market: the number of workers looking for work is exactly equal to the number of jobs looking for workers. But why would we expect that to happen? What reason is there to think that it’s equally easy for workers to find jobs and jobs to find workers? On the contrary, the ratio of unemployed workers to job openings never falls to 1.0, or hasn’t since we’ve had JOLTS to inform us.

S&D is simply the wrong model, based on a failure to distinguish between offers and transactions. Fortunately, there’s a better model out there, search theory, with fairly straightforward intuitions and tons of available data.

Anyone who waves an S&D model at me and makes claims about the labor market is simply advertising that they know less about economics than they think they do.

And most large employers are using algorithms to screen highly structured online application forms as a primary contact for prospective workers. What could possibly go wrong?

Algorithms have very specific bounds in which they are useful. When you try to use an algorithm outside its specific bounds, it will fail. How many employers actually know that?

How many employers would actually care?

and if it’s a situation where there are way more applicants than jobs, they have to whittle down somehow and I don’t think they care at this point whether it’s a rational reason or throwing away ever other resume or something (except the latter provides more legal cover maybe even though neither is actually discriminatory? I don’t know)

Lets remember, they are the victims because they cant find “qualified” employees…

How many vendors of HR-related software are going to say so in their marketing materials?

The way I see the labor market: the employer does not desire X amount of labor for his or her personal gratification — she desires X amount of work to gratify the ultimate consumer of labor and capital’s combined product and thereby influence the ultimate consumer to make a purchase.

If labor can withhold its portion of production to maximize its gratification with the price it charges — then labor joins capital and consumers in a balance of gratification all around.

This is not just academic. The typical labor market computations I see — often from so-called progressivie academics — completely and wholly ignore the monopsony-induced degradation of non-union labor which has no choice but to take whatever or starve (labor must be sold everyday or it rots).

Equal gratification of two but not three equals the destruction of the quality of life of the third — who constitute the overwhelming majority of society. So when are progressive economists (Krugman, etc.) and politicians (even Bernie) going to move re-building union density to the top of their to-do lists and keep it there until done?!

* * * * * *

In the day of the individual cloth weaver in Britain, the balance of market power between the weavers and buyer allowed the former a decent living. When steam looms made operators 100X? more productive, employee families ended up living on oat cakes three times a day because they couldn’t even afford wheat bread — because they had no way to withhold their labor to get a better price.

https://www.amazon.com/Making-English-Working-Class/dp/0394703227/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1499437487&sr=1-1&keywords=the+english+working+class+thompson

How many times does it have to be said? Do this or do nothing!

THIS CAN BE BEGUN AT THE STATE LEVEL

[cut-and-paste]

If (big if), back in the year 1935, when the NLRA(a) was passed, a few states had criminal penalties for union busting, does anyone think the NLRB(b) regulatory machinery would have nullified state criminal court prosecutions? Even if the NLRA/NLRB actually provided substantial protections back then (may have then; not-no more)?

Farm workers were deliberately left out the NLRA(a) in 1935 (to score enough votes). California (only) has a virtual mirror image of the NLRA(a) for farm workers — the CALRA. Should (a future Democratic) Congress move to include farm workers under the NLRA(a) — under federal preemption the the presumption is that the CALRA would fall to the wayside.

OTH, if Congress should wake up and make union busting a federal felony — triable and punishable in criminal court — there is no such presumption that state prosecutions would bowl over — no more than state bank robbery prohibitions or even state minimum wage regulations have to yield to federal preemption. (In any case, all previous convictions would hold — and any new prosecutions would simply take place at the federal level.)

THE SEATTLE STUDY SUPPORTS EITHER EXTREME OF THE MINIMUM WAGE DEBATE — either you cannot safely raise the minimum wage much even in the hottest (“gold rush”) economy in the country — or — there is a lot more money out there for wage raises than we ever suspected. Think about it. :-O

A hammer doesn’t care what the price of other hammers might be. Workers certainly care how much other workers are getting paid.

All models are wrong, but some are useful.

Especially when the actual question among our betters regarding labor is whether to go for full Biblical chattel slavery or just neo feudal rent a slave serfdom. To monetize the meat or not…that’s the question. Slave markets or serf markets (sharing economy)? That’s the real equation to graph.

I become more confused every time I see one of these diagrams disguised as graphs. A pair of orthogonal axes defines a space and the curves are paths within that space. This implies that each point along a path is related to the next point by a functional relationship between the quantities represented on the two axes. But I never see those functions expressly written out. Are they continuous? Are they differentiable and integrable? I guess I’ll just never understand economics.

Perhaps its not you – perhaps it is because economists don’t understand the difference between discrete and continuous functions? Or the concept of boundedness? And perhaps they don’t understand that even mathematics have to make sense?

I will be forever grateful for a physics professor back in my college days. He would give us problems that could easily give absurd answers. He was trying to teach us than plugging and chugging does NOT give correct solutions, but that we students have to always check along the way that our answers make sense in the real world….if not, then we’ve either made a mistake or the algorithms (formulas) we chose were wrong….

.. and why are the curves shaped the way they are? Why do they always look hyperbolic? Are the axes linear, or logarithmic? This stuff never made much sense to me ever since I took an intro course in economics three decades ago.

It’s nice to see that I’m not alone.

The nice thing about economics is that you can represent the graphical functional relationships however you might like — as long as you have sufficient “authority”. So — “Are they continuous? Are they differentiable and integrable?” — yes of course and no of course — if you like. There is plenty of abstract mathematics available for the purpose. It like the punchline to the question put to a candidate in an interview for an accounting position: “How much would you like it to be?”

“It is now commonly acknowledged that the origins of neoclassical theory were rooted in the imitation of the novel formalisms of energy physics which had been developed in the mid-19th century. … Components of the initial appropriation included equating “utility” with potential energy, ‘commodity space’ with n-dimensional Euclidean space, ‘price’ with force, and ‘trade’ with motion in space. The notion of “equilibrium” had not occupied pride of place in economic theory until after it was lifted wholesale from physics, as was the primacy of constrained maximization in its determination.”

[p. 13 (170) “2.1 The Physics Inspiration of Neoclassical Economics” section of “The Unreasonable Efficacy of Mathematics in Modern Economics”, Mirowski]

This post presumes the existence of Labor Markets in some abstract sense — whether supply-demand diagrams are appropriate or not. In theory Markets help set the price for goods and services. The question came up in the 1930’s: “Where do the prices for industrial commodities come from? The answer: prices are set by means of markup formulas or cost-added formulas to obtain what Gardiner C. Means termed “administered prices”. This concept was primarily applied to large highly concentrated national industries in the U.S. like steel production — at that time. Given our world of globalized production by even more consolidated corporations controlling large parts of the global economy I wouldn’t be surprised to discover administered pricing in operation for determining wages and affecting hiring practices. But how could a mechanism like that ever be seriously modeled as a Market for Labor?

Economics was not always so mathematical. Phillip Mirowski’s paper “The When, the How and the Why of Mathematical Expression in the History of Economic Analysis”,

[Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 5, Number 1—Winter 1991—Pages 145–157]

I think this paper may be available for download at [https://nd.academia.edu/PhilipMirowski] It’s relatively short and more readable than a lot of Mirowski’s writing and may be easier to pull-in than the previous reference. As I recall this Notre Dame site will ask you to create a login and provide your email address.

Great comment – and thanks for introducing me to Mirowski’s article: “The unreasonable Efficacy of Mathematics in Modern Economics”. I haven’t finished it yet, but I am impressed with what I have read so far! For anyone else who wants to read it, it is pretty interesting stuff!!

http://www.academia.edu/10286386/Unreasonable_Efficacy_of_Mathematics_in_Economics

Glad you liked the reference. I must confess I only read as far as page 13 where I found what I wanted. I am impressed by Mirowski’s insights but his vocabulary and the complexity of some of his analysis often taxes my ability to understand. I have to read some passages several times.

as an undergrad econ major, we never got past “assume a continuous function.” they admit that it is discrete data, but they want to be able to use calculus and be all fancy.

i think the implication is that such assumptions are lifted in grad school… who knows

Keynes noted in his General Theory that wages tend to resist being lowered during times of lower demand. Since most workers spend most of their money right away, they can’t afford to give back wages when the companies they work for aren’t doing so well.

So clearly, wages aren’t like other prices, at least as those prices are described in S-D graphs (or P-Q graphs, for that matter). Economists who think otherwise aren’t very good at economics, particularly since there have been economists who have known this for quite some time.

“Keynes noted in his General Theory that wages tend to resist being lowered during times of lower demand’

We’ve just seen in many western developed economies that this is not a universal and timeless economic rule, to say the least.

” Since most workers spend most of their money right away, they can’t afford to give back wages”

Or since most workers cannot afford to relinquish their incomes from labor for too long they do no have any option other than take cuts from the most powerful agents.

Honestly, such curves are only good for a rudimentary initial discussion. Even a product such as apples in a grocery store, prices are “sticky”. Where there is little demand, a grocer is more likely to throw out apples he does not sell than to lower the price. (Call these the “unemployed” apples.) Some people may want apples, but don’t have the time to go to the store. Or they are looking for a particular, rare breed, just as some employers are looking for particular skills or experience.

So you are correct, one should not use a Supply-Demand Diagram for labor, but neither should one use it for anything else, either.

That is what I believe to be correct, that S/D diagrams should never be used for anything except to explain a part of the complicated mechanism by which prices are determined. Every economics teacher should carefully explain to her students, “Always remember, in the real world there are many other things, including power relationships between buyer and seller, that affect this.” Most teachers don’t remember to do this. Mine certainly didn’t.

“Always remember, in the real world there are many other things, including power relationships between buyer and seller, that affect this.” Most teachers don’t remember to do this. Mine certainly didn’t.”

Very true

Is Dorman saying labour supply would equal demand if frictions from job search were removed? He doesn’t seem to be objecting to the use of wages as one axis but to the use of offers rather than transactions for the curves.

What about the notion that the demand for labour is derived from the demand for its output? I can’t tell if Dorman agrees. http://www.paecon.net/PAEReview/issue68/Grieve68.pdf

Simply put, demand creates and drives supply. Absolutely not the other way around. And there is no inter-relationship between the two that can be “plotted” on a 2D graph, because demand and supply are not two factors that are independent of the other. They themselves depend on other factors that affect both demand and supply. A model (for example, a supply & demand curve) that is too simplistic is wrong.

Why economists like S&D models is that it keeps the proletariat (labour, blue collar workers, non-professionals,…) without the whip hand. They don’t want labour to understand that without labour buying the things that are made (without labour’s demand that is), there is no need for the supply (the 1%ers, the factory owners, the ‘job-providers’).

Imagine a world without economists. How would heads of governments, leaders of manufacturing firms, and of worker organizations make decisions? Would things fall apart or would the world muddle through pretty much the same way it does now? I think the latter. Economists occupy the same place within the halls of power today that astrologers did 2500 years ago. Both have attempted to harness invisible forces that control human destiny. Both failed.

“Anyone who waves an S&D model at me and makes claims about the labor market are simply advertising that they are unthinking morons”.

Fixed.

My first grad level econ course was “History of Economic Thought.” As a get-to-know-you exercise the prof went around the room asking us to answer the question, “What is the function and purpose of economics as a discipline?” I answered that it was to rationalize and justify power relationships, most often between the haves and the have-nots.

Looking at me condescendingly, he asked whether I thought there was nothing objectively valid in the evolving methods, process and products of economic thought. I answered that there were, of course, exceptions which proved the rule, but that he had asked about the discipline as a whole. I did not get a good grade in the course.

Like all great thinkers, Marx got some big things right and some wrong. But “the reserve army of the unemployed” has, for me, capsulized more truth about labor markets in six words than all the graphs and equations I have studied.