By Elizabeth McGowan, a Washington, D.C.-based energy and environment reporter. Funding for this article was provided by a Solutions Journalism Network grant. Originally published at Grist

First in a series on communities overcoming obstacles to become cleaner and greener.

Sixteen months ago, the coal-fired Huntley Generating Station, which sits on the banks of the Niagara River, stopped producing power for first time since World War I.

Erie County lost its largest air and water polluter. But the town of Tonawanda, a working class Buffalo suburb 13 miles downstream of America’s most storied waterfalls, also lost its biggest taxpayer.

The impact of Huntley’s decade-long slowdown — and finally shutdown — hit this upstate New York community like a punch to the gut.

In just five years, between 2008 and 2012, Huntley’s pre-tax earnings tumbled by $113 million as it operated far below capacity, translating into a combined revenue hit of at least $6.2 million to the town, county, and local school district. That precipitous decline came when state education funds were also shrinking. Belt-tightening wasn’t enough; 140 teachers lost their jobs. Three elementary schools and one middle school closed their doors.

Rebecca Newberry, a 35-year-old former bartender and LGBT-rights activist, saw her home town facing the same fate that has befallen so many other Rust Belt communities that fell on hard times following an industrial exodus. She was determined not to let it happen to the place where she grew up. And she was fortunate enough to find a diverse group of allies who were willing to fight for their survival.

By combining the resources of her nonprofit, the Clean Air Coalition of Western New York, with area labor unions and other community groups, Newberry helped to hatch a plan for Tonawanda’s next chapter — and provide an inclusive, equitable template for other blue-collar towns facing the loss of dirty energy jobs and other polluting industries. (The jargony term for this in advocacy circles is “just transitions.”)

The retired Huntley Generating Station on the banks of the Niagara River. Google Earth

The retired Huntley Generating Station on the banks of the Niagara River. Google Earth

The group that Newberry helped form would come to be known as the Huntley Alliance. The partnership convinced New York lawmakers to provide Tonawanda with a temporary cash infusion to sustain the town as it reinvents its tax base — the first time a state has offered a financial cushion to a community that was financially reliant on a coal-fired power plant.

“It was a trauma when Huntley finally announced it was closing,” Newberry says, “so we had to come at this from a place of healing. Our goal was to stop the bleeding to the industrial and public sectors.

“Always, our key question is: How are we going to take care of our people?”

Team of Rivals

Tonawanda, a Native American word meaning swift waters, was founded by white settlers in 1836. East of the railroad tracks that run north from Buffalo to Niagara Falls, the 20-square mile town has nearly 73,000 residents and is known for its top-flight paramedic service.

But west of the tracks, it’s anything but quaint. Huntley and 50-plus industrial facilities coexist within a three-mile radius, mingled with older homes and trailer parks. Big grinding trucks assault the ears, and the air carries a distinct petroleum-rubber-chemical-exhaust stink.

The energy giant NRG purchased Huntley in 1999. Although the oldest current coal-fired unit dates back to 1942, the facility’s steam-generating history stretches back to World War I. NRG retired half of the plant’s 760-megawatt capacity in 2006 and 2007, with a corresponding drop in tax revenue.

In the fall of 2013, Peter Stuhlmiller, president of the Kenmore-Tonawanda Teachers Association, reached out to Richard Lipsitz, president of the local AFL-CIO chapter, to figure out how to save the community’s schools. They were soon joined by Newberry’s coalition, the Sierra Club, and trade unions representing steelworkers and Huntley employees.

“This country has a very poor record of rescuing communities built up around coal and heavy industries,” Lipsitz says. “Our goal was to stabilize the economy and provide income for a town that needed it desperately.”

Huntley Alliance members Rebecca Newberry (top left), Richard Lipsitz (top right), Peter Stuhlmiller (bottom left), Diana Strablow (bottom right) Elizabeth McGowan

Although their goal was the same, the various factions in the early Huntley Alliance had different priorities. The united front fell apart when a local Sierra Club member organized a protest calling for Huntley’s closure — with some demonstrators wearing union shirts. Labor leaders felt the rally threatened the livelihoods of the 70-plus remaining NRG employees. Finger-pointing ensued, and the plant’s union walked away from the nascent alliance.

Then the whole effort collapsed.

Newberry’s Clean Air Coalition didn’t join the Big Green’s call for Huntley’s closure — although it harangued other major polluters along the industrial waterfront during its decade of existence. The group’s leaders saw no need: The coal plant’s obsolescence seemed imminent with cheap natural gas flooding U.S. markets.

To motivate the Huntley Alliance to regroup, Newberry circulated preliminary results of a study her 200-member nonprofit commissioned. “Given that the plant is located in a region with substantial excess capacity for at least the next decade, the Huntley units appear ripe for retirement,” the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis concluded in a 24-page report released in January 2014.

“Going through this helps me to visualize that we can do better as a society,” Newberry says. “We don’t always have to be fighting with one another.”

At least 1,500 members of the steelworkers union live in the Tonawanda area, many drawing paychecks at employers such as Tonawanda Coke, 3M, DuPont, and Sumitomo Rubber. They backed the alliance’s focus on job retention and creation, because they feared property taxes would spike after Huntley’s shutdown — to make up for lost revenues from the plant. That could spook existing employers and repel potential newcomers.

“We want to make sure there are good, clean, high-road, family-sustaining jobs that improve the quality of life,” says Dave Wasiura, the union’s organizing coordinator for the area.

Retired teacher Diana Strablow, a member of both the Sierra Club and Newberry’s group, was initially frustrated that the dangers of climate change sparked by coal-fired power plants weren’t the alliance’s number one priority. But Newberry helped her understand how a stumble by Huntley could mean a fall for her entire community.

“I was the angry environmentalist,” Strablow says. “I’ve learned we need to take care of both our workers and our environment.”

Don’t Ask. Tell.

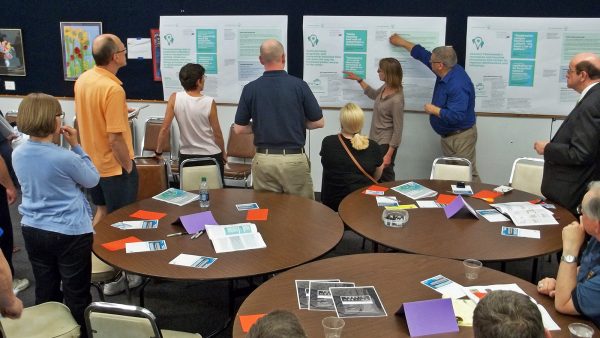

Once reunited, the Huntley Alliance needed clear goals — specifically ones that met the needs of the town’s residents. Through a series of listening sessions, door-to-door surveys, and voter-registration drives, the partnership channeled the hopes and anxieties of hundreds of residents. The wish list that emerged included keeping schools intact, creating good-paying jobs, expanding the tax base, and improving public health and the environment.

Those desires would be compiled with proposals and needs of businesses and other stakeholders into Tonawanda Tomorrow, a succinct blueprint for the town’s trajectory. A final version was released in June.

It was a tall order, so the alliance set about lobbying New York state legislators for “gap funds” to keep the town afloat during its transformation. After all, Newberry reasoned, Huntley had supplied electricity far beyond Tonawanda’s borders. Rather than asking lawmakers to find money for them, Newberry and her colleagues combed through the state’s budget themselves and compiled a list of potential funding pots to draw from.

By August 2015, when NRG announced Huntley’s impending retirement, a Democrat-majority State Assembly and a Republican-controlled Senate had already voted to back the alliance’s brainchild. When the 102-acre power plant went offline seven months later, the framework was in place for $30 million.

Cynthia Winland, a planning specialist at Chicago’s Delta Institute, praised New York legislators for being brave enough to act on Tonawanda’s financial request. Her sustainable solutions nonprofit helped assemble the town’s blueprint.

“If a state as geographically, politically, and economically complicated as New York is capable of this,” Winland says, “then other states can look for parallels.”

Community members give feedback on a draft of the Tonawanda Tomorrow plan at a public workshop in May. One Region Forward

This spring, legislators expanded the Huntley-inspired measure — in part due to Governor Andrew Cuomo’s announcement last year that New York would strive to be coal-free by 2020. The gap fund’s budget ballooned from $30 million to $45 million, its availability was extended from five to seven years. (It now covers communities with plants powered by any fuel source.)

The initial funding makes Tonawanda’s post-Huntley metamorphosis viable, Newberry says, adding that the two-year extension “gives us the extra breathing room we will need.”

The fund so far has shored-up the school system — which is no longer hemorrhaging teachers — stopped electricity bills from skyrocketing, and kept the budget for the prized paramedic unit intact.

David Schlissel, a coauthor of the 2014 report questioning the Huntley Generating Station’s viability, emphasized that the alliance’s proactive approach and the New York legislature’s response offer a vital lesson for the rest of the country.

“Instead of spending millions on propping up coal plants,” Schlissel says, “we need to spend money to help communities make an economic transition.”

The Huntley Alliance took its cues from other communities forced to evolve beyond heavy industry. Members traveled as close as Appalachia and as far as Germany, where they were amazed to witness how the German government funded worker retraining programs and recycled old production plants, as renewables supplanted fossil fuels.

“That gave us hope that a cleaner environment can be achieved in Tonawanda without leaving broken workers behind,” Newberry says.

Back home, the alliance’s efforts also benefitted from a $160,000 grant from an Obama administration initiative to help communities distressed by the demise of coal. President Trump proposed defunding the program in his 2018 budget.

Not Another Bethlehem Steel

Even with all the planning, the Huntley station’s idle smokestacks cause jitters among Tonawandans who have watched the 1,000-acre Bethlehem Steel plant idle in Lackawanna, 20 miles to the south, for three and a half decades. References to the hulking carcass send shivers down the spine of Tonawanda Town Supervisor Joseph Emminger.

“We are not going to have another Bethlehem Steel here,” he declares.

County and town planners view the reinvention of the Huntley site as a vital part of transforming 2,300-plus brownfield acres into greener ventures. Recent cleanups have allowed existing companies, such as Sumitomo Rubber, to expand and invited in newer industries, such as solar technology and warehousing operations.

“It’s a 20-year-long, step-by-step process,” says Erie County Director of Business Assistance Ken Swanekamp. “We’re doing it one project at a time.”

Tonawanda Town Supervisor Joe Emminger addresses the crowd at the second public workshop to draft the Tonawanda Tomorrow plan in February . One Region Forward

Possibilities for what could fill the Huntley site were tossed about at Tonawanda Tomorrow sessions. They included a bioenergy plant, an industrial heritage museum, and much-needed green space. River access along the town’s six miles of shoreline is now limited to one sliver of parkland south of the power plant.

That’s in contrast to the town’s northern neighbor — a significantly smaller city, confusingly also named Tonawanda — where a lush, verdant ribbon beckons visitors to the riverfront. A pockmarked bicycle/pedestrian path in the town suddenly turns pristine at the city line.

“We have a clear pathway forward,” Newberry says. But questions about what will become of the Huntley site make it clear, she adds, that “our work is not over.”

Unlike the Bethlehem Steel site, Huntley is not eligible for New York’s Superfund Program, says Erica Ringewald, a state Department of Environmental Conservation spokeswoman. However, NRG or a future owner that takes on the remediation effort could qualify for tax credits through the state’s brownfield cleanup program.

A preliminary to-do list at the site includes moving an 11-acre pile of unused Powder River Basin coal to a 116-acre NRG landfill about a mile away; closing a coal-ash lagoon; and continuing to clean 11 petroleum bulk storage tanks. But according to a state environmental assessment, contamination levels there do not “represent a significant threat to human health or the environment.”

“I don’t have a crystal ball, so I don’t know how long this takes,” NRG spokesman David Gaier says, adding that the company is just beginning the long-term decommissioning process for Huntley. “But you don’t go from a working power plant to condos in a year.”

Emminger, the town supervisor, isn’t envisioning condominiums — or any other type of housing — at the waterfront site. “Residential is too risky there,” he says, adding that light industry is more likely.

“We have a proud industrial past,” Emminger notes. “Hopefully, it’s going to be part of our future.”

I have a foreman who lives about a mile from there, he tells me that everyone on his block has some form of cancer. He’s serious and I believe him. Cancer research and treatment is one of the fastest growing and largest employersin Buffalo. However as someone who works in a skilled trade, the deindustrialization of this area has been absolutely devastating, with all the opioids and financial predators, there are people bying every day who used to have jobs…

Have family and friends sprinkled throughout the region with cancer histories. Bring the jobs back, yes, but without the pollution, please.

Good luck to them as they will need it. I visited Niagara Falls NY as the wife has always wanted to see the falls. I knew nothing of the area so I booked a hotel room on the NY side of the falls. I was shocked by how poor and depressed the area is. At least 50% of all the retail space was empty. The roads were literally patchwork pothole filling as far as the eye could see and everywhere you drove.

Going through the neighborhoods was no better as the homes were run down with many boarded up. I know I am making a big assumption here, but it appeared as if the entire area around Buffalo and Niagara falls suffers from the rust belt syndrome of relying on heavy industry and the ensuing collapse after the post industrialism age.

The incompetence, corruption, shortsightedness and stupidity of the local .gov(primary blame) and state .gov is on full display here. After leaving I had to read about the area as I was shocked that someplace that has one of the wonders of the natural world could be so rundown. Corruption and incompetence were indeed huge factors.

Niagara Falls NY is where I was born. Although much worse now (almost every small town in Upstate NY matches your description of the Buffalo area nowadays) for what it’s worth, Niagara Falls, NY was always a grubby, dirty town compared to Niagara Falls, Ontario.

Corruption may be a part of it, and may have been a part of why it looked like a dump back in the 50’s when economic life was good and most of NY State was thriving, but the bottom-line is that Niagara Falls has been a run-down tourist town for at least the last 60 years.

Also, don’t discount the goodfellas that still hold sway in Niagara Falls and Buffalo, although certainly not to the extent they did back in the 60s and 70s, the height of the mafia. There are still plenty of no-show jobs in WNY to this day.

There is talk of closing the Ginna nuke plant in Ontario, NY(my mother lives there). It’a about an hour and a half east of Tonawanda up on Lake Ontario. The county and town have been terrified about this happening due to the large amount of tax the plant pays(largest in county). Residents are worried about property and school taxes going through the roof. The plant was opened in 1970 and things keep dragging along.

My mother is from Buffalo and her mother was from Tonawanda. Both of them left the area and never looked back. This story gives me more of an understanding of the reasoning behind their decision.

The Niagara River region (where I grew up) is one of the great hydropower sources in America. But it is exported. The locals got electricity from a dirty coal plant. And when that closed, they’re faced with higher prices.

This story also reminds us of the long-term underinvestment in America’s electric grid, which makes the shutting of a power station a disaster for the local people because power cannot effectively be redistributed as needed.

And it reminds us of the backwards-looking myopia of US corporate management. Just as that massive Bethlehem Steel plant was obsolete on the day it opened, NRG bought the Dunkirk and Huntley coal-burning stations in 1999 — invested millions of dollars in low sulfur fuel conversion — and then closed both.

http://www.power-eng.com/articles/print/volume-113/issue-4/departments/managing-the-plant/coal-switch-helps-new-york-plants-stay-competitive.html

Trivia note: the two Tonawandas are not “confusing.” This article is about the Town. Their northern neighbor is a City.

The Niagara Falls power plant is truly sustainable green power because, unlike most other hydropower plants, it did not require building dams to turn flowing rivers into lakes. The natural head loss in the falls powers the plant.

My spouse was born and raised in Jamestown, NY, 70 miles south of Buffalo, on the Chadakoin River draining out of Lake Chautauqua. It was once one of the largest furniture-making cities in the US, due to the happy confluence of water power, forests and Swedish immigrants experienced in carpentry … and tree cutting. It is now decaying and economically depressed.

Jamestown owns and operates its own electrical generating plant; originally coal-fired, it is now being converted, boiler by boiler, to natural gas. In 2012 a citizens’ coalition defeated the city’s plan to build a new multi-million dollar coal-fired generating plant.

Reading about the history of the plant, it looks like they had experimented with providing heat to nearby businesses at one time, but this effort seems to have disappeared.

We are right now in the process of moving back there, since my recently-retired spouse has a family house and land and lots of cousins who farm in the area. Most days, I’m like, I must be crazy!

This appears to be a heartening and hopeful start to the process of community-survival and revival in the teeth of such a big-employer collapse. It was heartening to see how several different sorts of educated and literate working-class sectors and their leaderships were able to work together on this. It was also heartening to read about how the Sierra Clubber was able to climb down from the Sierra Club’s usual position of greener-than-thou virtue-stuff-strutting superioritude. If the Sierra Club had remained opposed to this effort, would the other elements of the coalition been able to stay together and crush and smash the local Sierra Club and tread its carcass into the earth? That may be a very relevant question for other communities which face the same big-employer closures, have the same greener-employment hopes, and have a nasty dog-in-the-manger Sierra Club in their midst.

If this community has a large percent of its people living in detached suburban houses with yards, they might also look into rooftop water harvesting and storage, waterless compost toileting, hyper-dense suburban foodgrowing, and other modernized neo-subsistence production methods and approaches which make having normal amounts of money less necessary for survival. After all, the food you can grow equals the money you don’t need to make for the food you don’t need money to buy because you can grow it. That might be the “other leg” of viable survival.

Good article. In my part of upstate NY, we get a few from Buffalo, including some close friends. Great people, a lot of heart, and unlike some other post-industrial NY cities, proud of where they’re from in the best way.

In terms of energy, the long and short of it is the Ontario region is in for a lot of pain. Coal, Nuclear and Hydro – all will lose nearly all their profits due to the perfect storm of cheap natgas (we’re on top of the Marcellus shale), and subsidized wind and solar. I favor subsidizing wind and solar obviously, but the collateral damage is that you completely wipe out nuclear (in economic terms), even though it is also carbon free – while natgas will always be there because it’s the most economical electricity that’s there 100% of the time.

Once coal goes (the sooner the better for the environment), the wholesale price of electricity is bound to vary between the fuel cost of natgas at the high end ($0.02 to $0.04/kWh), and zero at the low end, if wind/solar gets overbuilt. Neither wind nor solar alone can take out natgas due to the need to have something 100% of the time.

Due to the higher availability of wind, wind will take out the solar (for this geography) before batteries can take out natgas for baseload on non-solar/wind days, which is probably 20 years off. We will end up subsidizing natgas too, before it can be replaced. There’s a lot to digest to this story. From a national perspective, it would be better, perhaps, to subsidize the people (health care?). From a carbon perspective, it would be better to subsidize early retirement of coal in 3rd world countries.

To what extent would it be possible to subsidize the reduction of electricity use? If overall use of electricity throughout the region were reduced to where wind and solar plus storage for intermittent excess of wind and solar for re-release when wind and solar were real-time short, then NatGas could be reserved for direct heating and cooking uses, industrial process heat, making into chemicals, etc.

Burning a fuel into electricity is the most wasteful thing one can do with that fuel, given how much of the liberated heat is lost between the flame and the final electric current coming out the socket. Think of it like this: If you have an electric stove, how much NatGas must be burned to make and ship enough electricity that some of it gets to your electric stove? Whereas, if you have a gas stove, how much less gas do you have to burn right there in the stove in order to get the same amount of heat to cook the same potful of food?

If people did non-electrically every single thing which can be done non-electrically, how much less electricity would even be needed? What if people truly believed and truly lived out the belief that electricity should be reserved for the things which only electricity can do? How much less electricity would we be using?

@dc

IMO, Yes to subsidizing reduction in electric use, via subsidizing efficiency. Because if you subsidize generation encourages use. And the generation subsidy’s effect on reduce electric prices will happen fast (5-10 yrs, we’re almost at that point now), while the intended effect of retiring fossil fuels will take 20-30 years.

You can subsidize energy efficiency for heating/cooling too. For example, NY state gives credits to upgrade insulation in old houses and there is an entire cottage industry of insulation installers whose business lives off those credits).

As for the cost/benefit of burning natgas (or any fuel) for electricity vs heat?

I apologize, but I can only respond to that with some thermodynamics.

Tha basics: If you have some amount of “energy”, it can mean different things. Electricity is a very high quality form. Mechanical and gravity are the highest. Heat is a relatively low quality form of energy. The relationship of heat to the others depends on essentially on temperature (or equivalently compression ratio in a car engine). If your generator can burn your fuel at high temperature and pressure, you’ll get more electric or mechanical energy for the same amount of heat. You need exotic materials and investment in a variety of complicated tricks to do that, and to squeeze the most electric/mechanical energy out of the heat that carbon based fuels contain.

This means burning the fuel in a power plant is favorable, vs in a small engine for a household.

However – the waste heat from electricity generation is … wasted. In places with high population density, it can be used to heat water and pipe hot water to apartment buildings. And the energy-generating potential of natgas is wasted when we simply burn it for heat in our homes. In that case, we could run the natgas through a small diesel, and still get the same amount of heat when heating the house, but get some electricity as a bonus (albeit with lower efficiency than a power plant).

@p7b,

I reread your comment with more time available and therefor more care, and I see your reference to burning NatGas in a tiny power-plant right there in the residential home, to get some electricity and heat the home. I believe I have read that very expensive little heat-and-power plants exist on just that principle in Switzerland and northern Japan. I am not sure how to look up about them on the web. And you are right, it seems like a good idea to me if the initial home micro-power plant could be affordable. The low temperatures ( only a few hundred degrees ) needed to heat water or indoor air to the desired temperature make this seem like a good idea on its face.

In the very narrowest sense, then, I still think using gas to cook with would be more efficient than turning gas into electricity to cook with the electricity . . . . because the gas flame would burn at or over a thousand degrees and the heat would run “downhill” very fast into the target potfull. But maybe I am even wrong about this. Maybe the experiment would have to be run.

And certainly using wind or solar electricity to cook electrically with is perfectly fine and entirely renewable, if you have so much home-made electricity you can’t use it all any other way.

@p7b,

Thank you for your detailed reply. Since I am on break I can only make the very briefest little comment in response.

I have to defer to your knowledge of relative heat-extraction efficiency of burning gas in a large power plant for electricity as against burning gas in a little engine right on-site for electricity. The large central power plant would be a more efficient fuel-for-electricity burner.

I was actually thinking of something else. I was thinking of doing on-site heating directly with fuel burned on-site as against fuel burned remotely, turned into some electricity for shipping to the heat-site and then degrading that electricity into heat by forcing it through resistant metal. For example, if you want to do some cooking, I suspect it takes less gas overall to ship the gas to the pot and heat the pot with some burning gas right there on-site, than if you had burned enough gas at a remote power plant to make enough electricity to deliver it to the pot and still have enough left over after all the losses along the way . . . to still heat the pot just as much. In that specific case, I think it would take less gas to heat the pot with burning gas than to heat the pot with electricity brought in from having burned the gas remotely to turn a turbine.

Would I be wrong to think that way?