Yves here. This post does a fine job of explaining, in a layperson-friendly manner, why one of the key tenets of mainstream economics, the loanable funds theory, is bunk. It’s nevertheless incorporated in models widely used by central bankers and Serious Economists like Paul Krugman.

The post shows how it has failed in practice. But what is more revealing is it was shown to be incorrect long ago yet orthodox economists refuse to give it up. From an earlier post, which explains the conventional argument first and then why it is wrong:

From [the Wall Street Journal’s Fed reporter Greg] Ip:

When central banks ease the supply of credit, they rely on banks to transmit the benefits to the broader economy by making loans, handling trades and moving money between people, companies and countries. Shrinking, unprofitable banks hobble that transmission channel.

This is the debunked “loanable funds” theory: that when money is on sale, businesses will go out and invest more. That theory was partially debunked by Keynes and dispatched by Kaldor, but zombie-like, still haunts the halls of central banks.

Businessmen see the cost of money as a possible constraint on growth, not a spur to it. They decide to invest in expansion if they see an opportunity in their market. The big exception? Businesses where the cost of funding is one of the biggest costs. What businesses are like that? Financial speculation.

And we’ve seen the failure of this tidy tale in the wake of the crisis. Providing super cheap money has not induced businessmen to run out and ramp up their operations. Instead, one of the biggest outcomes has been corporate financial speculation: issuing debt to buy back their own shares.

Further reading from our archives:

Martin Wolf Defends Central Banks’ Negative Interest Rate Policies

Philip Pilkington: Keynes and Loanable Funds

Philip Pilkington: Krugman Still Wrong on Monetary Theory (Loanable Funds Edition)

By Nikos Bourtzis, who recently graduated with a Bachelor in Economics from Tilburg University in the Netherlands. He will be pursuing a Master in Economics and Economic analysis at Groningen University. Originally published at The Minskys

Monetary policy has become the first line of defense against economic slowdowns — it’s especially taken the driver’s seat in combating the crisis that began in 2007. Headlines everywhere comment on central bank’s (CB) decision-making processes and reinforce the idea that central bankers are non-political economic experts that we can rely on during downturns. They rarely address, however, that central banks’ monetary policies have failed repeatedly and continue to operate on flawed logic.

What Central Banks Try To Do

To set monetary policy central banks usually target the interbank rate, the interest rate at which commercial banks borrow (or lend) reserves from one another. They do this by managing the level of reserves in the banking system to keep the interbank rate close to the target. By targeting how cheaply banks can borrow reserves, the central bank tries to persuade lending institutions to follow and adjust their interest rates, too. In times of economic struggle, the central bank attempts to push rates down, such that lending (and investing) becomes cheaper to do.

This operation is based on the theory that lower interest rates discourage savings and promote investment, even during a downturn. That’s the old “loanable funds” story. According to the neoclassical economists in charge at most central banks, due to rigidities in the short run, interest rates sometimes fail to respond to exogenous shocks. For example, if the private sector suddenly decides to save more, interest rates might not fall in response. This produces mismatches between savings and investment; too much saving and too little investment. As a result, unemployment arises since aggregate demand is lower than aggregate supply. In the long run, though, these mismatches will disappear and the loanable funds market will clear at the “natural” interest rate which guarantees full employment and a stable price level. But to speed things up, the CB tries to bring the market rate of interest towards that “natural” rate through its interventions.

Illustration: Heske van Doornen

Recent Attempts in Monetary Policy

However, interest rate cuts miserably failed to kick-start the recovery during the Great Recession. That prompted the use of unconventional tools. First came Quantitative Easing(QE). Under this policy, central banks buy long-term government bonds and/or other financial instruments (such as corporate bonds) from banks, financial institutions, and investors, which floods banks with reserves to lend out and financial markets with cash. The cash is then expected to eventually filter down to the real economy. But this did not work either. The US (the first country to implement QE in response to the Crash) is experiencing its longest and weakest recovery in years. And Japan has been stagnating for almost two decades, even though it started QE in the early 2000s.

Second came “the ‘natural rate’ is in negative territory” argument; Larry Summers’ secular stagnation hypothesis. The logic is that if QE is unable to increase inflation enough, negative nominal rates have to be imposed so real rates can drop to negative territory. Since markets cannot do that on their own, central banks will have to do the job. First came Sweden and Denmark, then Switzerland and the Eurozone, and last but not least, Japan.

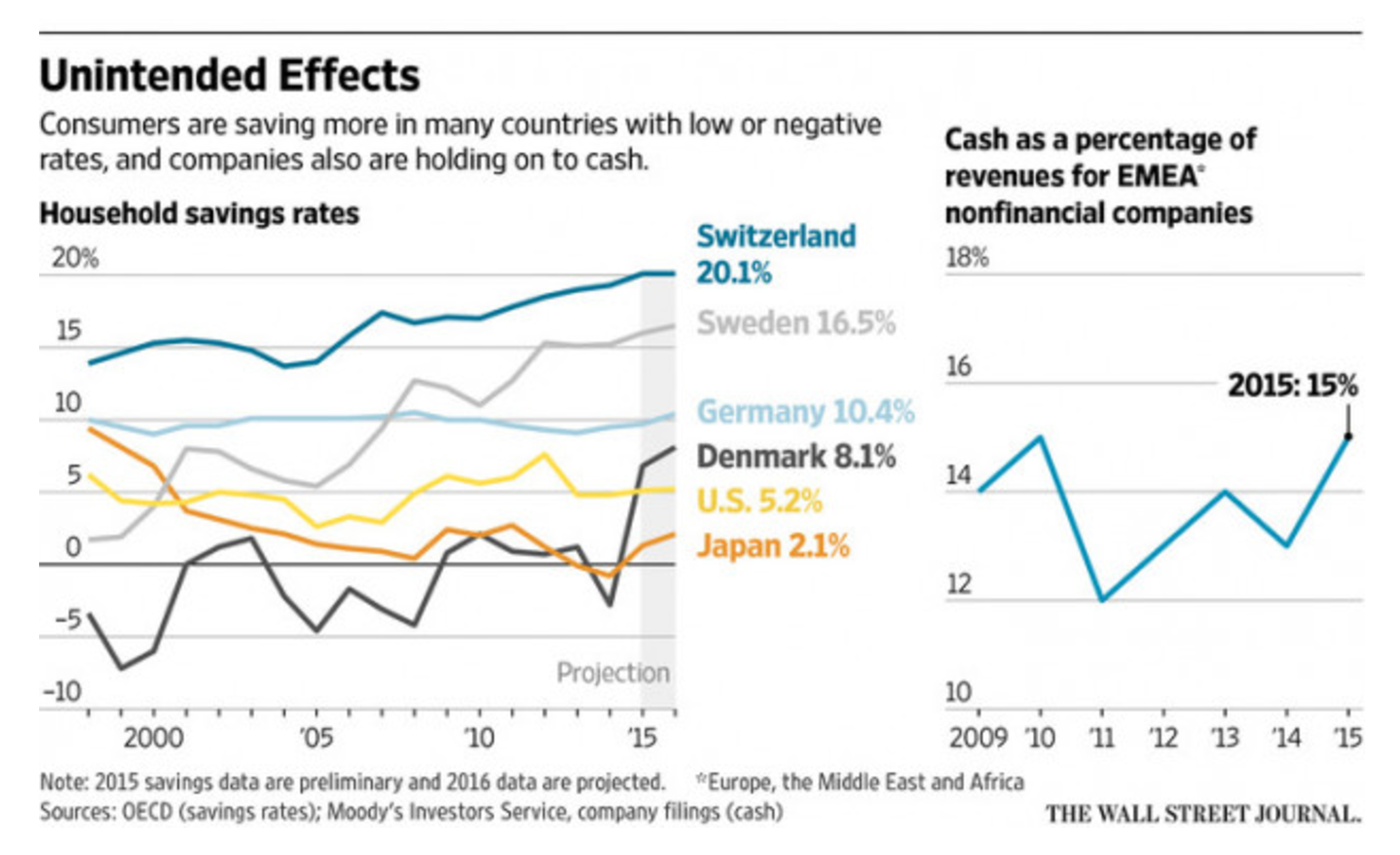

Not surprisingly, the policy had the opposite effect of what was intended. Savings rates went up, instead of down, and businesses did not start borrowing more; they actually hoarded more cash. Some savers are taking their money out of bank accounts to put them in safe deposits or under their mattresses! The graph below shows how savings rate went up in countries that implemented negative rates, with companies also following suit by holding more cash.

Central bankers seem to be doing the same thing over and over again, while expecting a different outcome. That’s the definition of insanity! Of course, they cannot admit they failed. That would most definitely bring chaos to financial markets, which are addicted to monetary easing. Almost every time central bankers providea weaker response than expected, the stock market falls.

There Is Too Much Private Debt

So how did we get here? To understand why monetary policy has failed to lift economies out of crises, we have to talk about private debt.

Private debt levels are sky high in almost every developed country. As more and more debt is piled up, it becomes more costly to service it. Interest payments start taking up more and more out of disposable income, hurting consumption. Moreover, you cannot convince consumers and businesses to borrow money if they are up to their eyeballs in debt, even if rates are essentially zero. What’s more, some banks are drowning in non-performing loans so why would they lend out more money, if there is no one creditworthy enough to borrow? Even if private debt levels were not sky high, firms only borrow if capacity needs to expand. During recessions, low consumer spending means low capacity utilization, so investing in more capacity does not make sense for firms.

How to Move Forward

So, now what? Should we abolish central banks? God no! Central banks do play an important role. They are needed as a lender of last resort for banks and the government. But they should not try to fight the business cycle. Tinkering with interest rates and buying up financial instruments encourages speculation and accumulation of debt, which further increases the likelihood of financial crises. The recent pick-up in economic activity is again driven by private debt and even the Bank of England is worried that this is unsustainable and might be the trigger of the next financial crisis.

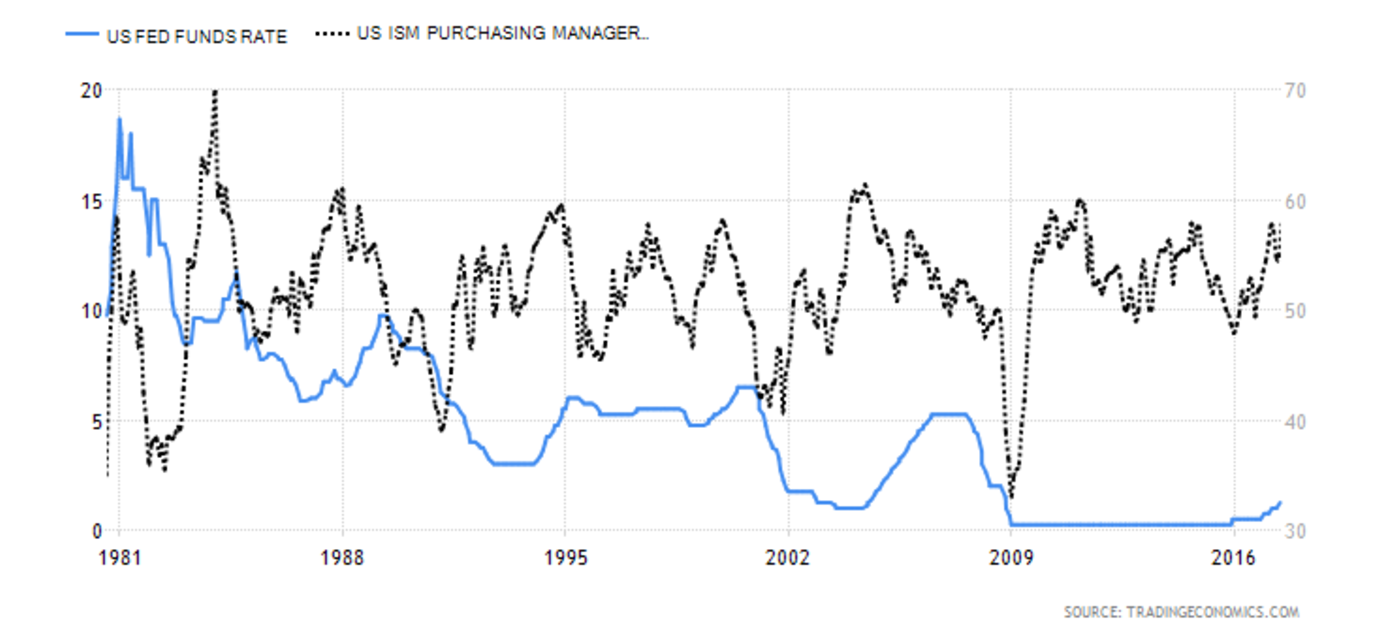

The success of monetary policy depends on market mechanisms. Since this is an unreliable channel that promotes economic activity through excessive private debt growth, governments should be in charge of dealing with the business cycle. The government is the only institution that can pump money into the economy effectively to boost demand when it is needed. But due to the current misguided fears of large deficits, governments have not provided the necessary fiscal response. Investment requires as little uncertainty as possible to take place and only fiscal policy can reduce uncertainty. Admittedly in previous decades, monetary responses might have been responsible for restoring some business confidence as shown in the figure below.

This effect, though, cannot always be relied upon during severe slumps. And no doubt, more attention needs to be given to private debt, which has reached unprecedented levels.

Monetary policy has obviously failed to produce a robust recovery in most countries. It might have even contributed in bringing about the financial crisis of 2008. But central bankers refuse to learn their lesson and keep doing the same thing again and again. They don’t understand that their policies have failed to kick-start our economies because the private sector is drowning in debt. It’s time to put governments back in charge of economic stabilization and let them open their spending spigots. A large fiscal stimulus is needed if our economies are to recover. Even a Debt Jubilee should not be ruled out!

Funding as a major cost center not only exists in financial speculation, but also in commodity speculation. This is a primary reason why commodity prices rose, precipitously, while The Fed kept the QE program switches turned on and why, after The Fed flipped the switches off, commodity prices dropped… until the ECB stepped in and commodity prices rose again, although the response has been more tepid, as currency exchanges have to be pursued.

What has been overlooked is how The Fed’s treatment of inflation as an isolated variable, as if in a vacuum, has been catastrophic, hastening the return of the next downturn. While artificially manipulated commodity prices created inflation, in the real economy where household incomes have stagnated or fallen, this removes even more monetary circulation at the mid levels, further sapping the wealth of middle income households. Discretionary income is drying up, as the purchase of synthetically inflated necessities requires an ever enlarging share of stagnant/decreasing HH incomes.

In a fully functioning consumer economy where incomes are increasing, only then can real demand ensue and thus, real inflation.

Since the late ’80s, American households have substituted income gains with debt gains, creating the illusion that we have had a functioning economy. The GFC of 2008 simply marked the first episode where the over-leveraged consumer hit the proverbial brick wall, unable to accrue more debt.

See the paper Synthetic Inflation on Google Drive for more details: http://bit.ly/1KHjBKy

+1000

Doing stupid things result always in stupid outcomes.

“However, interest rate cuts miserably failed to kick-start the recovery during the Great Recession.” Arguably, the very CAUSE of the Great Recession was the fact that interest rate cuts in response to the Dot-com bust failed to kick start that recovery. Sure people borrowed and spent, but without wage increases all that demand was backed by debt that was no easier to pay back when it was due than when it was borrowed, So that demand was borrowed from the future. And when that “future came,” we had the Great Recession.

Fiat sovereigns don’t understand main street. They don’t understand why the public and corporations don’t just turn on the fiat spigot like the fiat sovereign does … creating fake prosperity at every level. The problem since 2008, is that the spigot money has all gone to Dark Finance, and that is why we don’t have raging hyperinflation … yet.

“…that the spigot money has all gone to Dark Finance, and that is why we don’t have raging hyperinflation … yet.”

Since the monetary expansion has been spent on equities and dark finance INSTEAD of consumer products THAT is where we have seen rising prices. And since those prices are based on too much money chasing too little future profits we’ve seen repeated asset bubbles. Really some of the few goods and services that have been rising much are for products that are bought with debts that can be financed for long periods of time: real estate and college degrees. Healthcare spending has also gone up since the ACA increased spending without doing much to control costs.

The spigot money only goes those who already own the assets. All the inflation is in asset markets: stocks, bonds, high end residential and commercial real estate and trophy paintings. It’s all a big scam but nobody seems to understand that the Fed is the cause of all this. We keep looking to it for salvation. It’s all quite comical at some level and the ignorance surrounding this subject is astounding. Also very tragic. It will come to a head one day.

Wow. What an excellent article.

When the Federal Reserve announced their ZIRP and QE exercises, I expected us to see a lot of inflation, but it didn’t happen. It took me a little while to figure out why prices on general consumer goods weren’t rising, but then I finally realized that none of the money was reaching the pocketbooks of general consumers. When wages are stagnant, businesses can’t raise prices on consumer goods or services even if they want to. Their customers couldn’t afford it.

Instead, all of the extra liquidity went into asset markets: stocks, bonds, commodities, and housing. All of these rose sharply. If you were fortunate enough to already have substantial holdings of these assets (i.e., already be rich), then the ZIRP and QE eras were very good times. Indeed, income inquality rose significantly faster under Obama that it did under Bush as a consequence of these policies. [I personally consider ZIRP/QE one of the greatest mistakes of the Obama years.]

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2012/04/growth-of-income-inequality-is-worse-under-obama-than-bush.html

http://www.newsweek.com/2013/12/13/two-numbers-rich-are-getting-richer-faster-244922.html

The Federal Reserve currently has two “mandates”, but they really ought to add a third:

[1] Keep prices stable (i.e., inflation low).

[2] Maximize employment.

[3] AND DON’T BLOW ASSET BUBBLES.

Realistically, this would be accomplished by always keeping interest rates above asset appreciation rates, so that people couldn’t engage in the (ahem) time-honored tactic of “buy asset on credit, wait for asset to appreciate, then sell asset for profit” with any reasonable chance of success. And without borrowed dollars flowing into asset markets, prices would quickly collapse to saner values. Wall Street’s importance would be reduced, and housing would become affordable again.

” They don’t understand that their policies have failed to kick-start our economies because the private sector is drowning in debt.”

The same was largely true in 1929-30. The financial men in 29-30 pursued the same policies they had used the preceding 20 years thinking said policies would continue to work.

“Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate. It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up from less competent people.”

– Andrew Mellon

Today’s low interest rate/ QE/ monetary policy looks like the opposite of ’29 and ’30’s response.

In some respects it is exactly the same: pursuing a policy that worked in the past but no longer works. (Assuming that propping up the TBTF financial sector that caused the problems at the expense of the real economy is any sort of long term fix.)

Thanks for this post.

They don’t understand that their policies have failed to kick-start our economies because the private sector is drowning in debt.”

Actually, I think they do understand that their policies have succeeded very well indeed.

The health or not of “main street” was always a secondary issue to the Fed, & central banks generally. Their primary goal was to stabilize & empower the FIRE sector. A private sector “drowning in debt” is (within reason) a very good thing. It means the rentier class is taking an increasing amount of surplus. Almost free money allows corporate Executives to engage in various forms of financial self-dealing, such as share buy-backs funded by loans of some kind.

To suggest that Central banks did not “understand” what they were/are doing is to stretch credulity beyond breaking point…

Also worth mentioning is the ideological position of Neoliberalism generally (& Wall St, the Fed, & FIRE sector in particular): monetarism largely cuts government out of the macroeconomic equation. In fact, it makes government appear helpless. Fiscal policy, of course, has the opposite appearance: it’s government taking direct action on the economy, with quite possibly, positive results. That would not look good, would it ?

I happen to think then are a bunch of academic clowns but maybe that is just their cover. As you say it is beyond reason to think they are as dumb as they appear. Also when you go back and study the whole history of the Fed and the people associated with it, it sure looks like some type of power structure.

I agree that it stretches credulity but I wouldn’t want to underestimate the capacity of people for self-serving delusions. Especially people who have been well served by those delusions.

Two sources of money:

Central Banks – available as loans which need to be repaid

Government – which cam give money directly to people, but:

1. “It has to be repaid” becuse some people thing the Government “borrows” money

2. It would not flow to the politically connected, so there’s nothing in it for me and mine

3. In the US I have trouble believing our political leaders are color blind:

The war on Marijuana stated as a concealed racist attack on Mexicans

The was on drugs was a concealed racist attack on blacks (Crack sentences vs Powdered Cocaine sentencing).

In other words I believe our elected representative mostly racist, and especially n the UK classist (not one of us), to the core, and this prejudice spills over into the laws and governance of the land.

If there is more reasonable opinion of why, for example, the “war on drugs” was established, and has continued for so long when first it is patently obvious that first it has failed, and second no one is the drug suppression business has any desire to succeed because it would end their employment, and third it provide an culture of fear to keep the uppity poors (and people of color) subjugated.

And, I’m fully aware I am attributing intent, greed, malice and prejudice to our governing class.

This is not a sterile issue of economic models, it should be a political discussion of the deliberate malice exhibited by our ruling class collectively towards the people they purportedly represent, but in practice disrepresent.

Australia is considering going cashless and one Aussie even suggested putting an expiration date on digits/credits so they aren’t hoarded. I think sometimes we get inflation mixed up with aggressive over production – beyond the needs of demand, mostly for the sake of competition. Never really hear about that distortion, we just ignore it because groaf. We prolly do need 2 kinds of money. One for exchange, with a use-by date (good idea) and another for capital shares, with a long shelf life. But when money is both a medium of exchange and a store of value it can be very confusing because those in a position to do so can grab or hoard money to game the system, invest it irresponsibly, create insane levels of debt, etc. Whereas a functioning economy would have prevented the worst of these distortions. It has become obvious that the conflict within the idea of money itself can destroy the real economy. Somebody please tell Janet.

I find the debate about central banking always posits that a central bank must necessarily exist in the first place, it reminds me of a coven of priests, poising to explain the complicated movements of the universe, starting with the premise “The Earth is at the center”.

So let’s recall for a moment that the great majority of the huge arc of human progress took place without any central banks whatsoever being in place.

Then the tinkering began. Banking and liquidity crises resulted in economic disruptions that people sought to mitigate. But why? Imbalances always corrected, and usually quite quickly. Ponder for a moment where we’d be if Bernanke had had The Courage NOT To Act, we’d have cleared out the dead wood in that much-parroted-but-never-followed effect called Capitalist Creative Destruction. A few years of deep pain, yes. But where are we today? 9 years on and banks and the economy are still on “extraordinary temporary emergency measures” and systemic banking risk is more concentrated than ever. Do we believe in Capitalism or don’t we? Do we really want to keep Endless Socialist Life Support For Banks? What about all of the other zombie companies we prop up with the butcher’s thumb on the price of money?

Ah, the price of money. If you told people that the price of the very lifeblood of the economy is set by a (presumably omniscient) Soviet Central Planning Politboro based on inputs they cannot even measure, let alone affect, how would they react? Have you ever looked at the forecasts of central banks? (I’ll save you the time: they are WRONG 100% of the time. Not 99% of the time, or 98%).

Which brings us to the creeping mandate: Let me get this straight, they are supposed to “ensure adequate liquidity to the banking system during periods of stress” (probably an OK start); but now, in addition, they are responsible for the solvency of banks too; and they are supposed to try to keep prices “stable” (presumably through omniscient forecasting); AND they are supposed to control when and where businesses hire people too? (the unemployment mandate).

“I have seen the future…and it works!” is what the architect of this top-down command-and-control monetary system, Harry Dexter White, said in 1936 after he returned from a visit to that shining model of all future societies: the Soviet Union. I just wish a blog like this would really try and pry this subject open by considering the very foundation of the debate. We lament “central banking is failing” without really digging in to understand what it is or why it’s there in the first place.

When creating and maintaining social structures, a tension exists between decision making and living with the outcomes. There will always be winners and losers in any decision. Class structures in human societies provide a ready made template for rulers/designers, simplifying their task by not having to justify the distribution of goods and services generated by the population every generation. To get to the foundation of all arguments concerning human activity, the discussion must be grounded in class distinctions and their function in the broader society.

The complexity of the world prevents any human central planner or designer from accurately predicting outcomes in a broad spectrum view. What matters in the end is Power and the willingness to exercise its use.

What we need today is the sentiment, “Its Class stupid”, to break through in social consciousness.

In a modern world, people in power cannot have that for a second. That would bring about a trajectory to a truly sharing economy.

@openthepod……

very good point. It is worth revisiting the entire premise behind all this. It’s also worth revisiting the real powers behind the push for a U.S. central bank. This whole crypto-currrency block chain thing has the power to reorder the system but I don’t thin it will be allowed to happen. To many powerful forces aligned against it.

Some people do attempt to put facts behind the monumental decisions on how money should be created and distributed. Let me offer a few:

The US did not even have a real central bank until 1913. The decades prior to its creation were periods of huge economic growth and rise in real incomes and standard of living of Americans, periods unmatched to this day.

This period was also marked by extended periods of deflation, where prices fell by >50%. Rising productivity and declining prices used to be called by a different name: progress. The Malleus Mallificarum today’s monetary priests recite from by contrast insists that declining prices somehow are evil.

On his deathbed Woodrow Wilson finally lamented signing off on the creation of the Fed: “I am a most unhappy man. I have unwittingly ruined my country. A great industrial nation is controlled by its system of credit… all our activities are in the hands of a few men”.

End the Fed.

“Ponder for a moment where we’d be if Bernanke had had The Courage NOT To Act”

Bankrupt u Bernanke was the sole cause of the GFC (as anyone who reads his book would know).

Claiming Bernanke is the sole cause is a little unfair to the Great Greenfool, Little Timmy G., Larry Dumbers, Gary Gorton, Glen Hubbard and a whole host of other intellectual clowns who helped lay the groundwork for the GFC.

Another +1000!!

(And so many other fools not listed!; and the problem most of them have been hanging around during multiple administrations blowing their foul financial advice smoke)

This post is fundamentally mistaken.

(1) “Monetary policy has obviously failed to produce a robust recovery in most countries.”

This is sophomoric exaggeration. Monetary policy is a tool, not a magic wand. An useful evaluation of monetary policy would consider its net effect, especially with estimates of where we would be if Central Banks had not applied strong monetary stimulus.

(2) Looking at the US, monetary stimulus ended in November 2014. That’s a long time ago, on the scale this post discusses.

Since then the Fed balance sheet has been flat — the primary indicator of monetary policy. Change in the balance sheet reflects monetary stimulus or slowing.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/datatrends/usfd/page7.php

Also, market set interest rates have remained more or less flat despite continued economic growth. There is little or no evidence that the Fed is “suppressing rates” as conservatives claim.

If monetary stimulus were helpful to the economy, would you not expect to see it reflected in job creation numbers?

Your chart from the Fed shows big jumps in the balance sheet associated with QE1, QE2, and QE3. However, when I look at total private sector employment from early 2010 through today, I see no corresponding jumps. Heck, I don’t see any change in the slope at all. It’s a straight line, with a value for slope that is disappointing at best.

https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CES0500000001

If we weren’t getting any measurable boost in jobs from QE, then why were we bothering with the effort at all?

[Personally, I think that the monetary stimulus was helpful during the actual recession, i.e., the period where we were actively losing jobs. However, as soon as the job situation turned the corner (arguably in early 2010), the Federal Reserve ought to have started “policy normalization” efforts. Not waited until late 2014 to end QE and until 2017 to end ZIRP.]

Employees and wages are a cost. It has been pretty clear in this cycle that businesses are looking to cut, or at least control, those costs in order to push earnings up. So they squeeze their employees and any subcontractors. Low interest rates have also helped them buy back shares to push up per share earnings.

Companies have not focused on pushing total revenue up because that would require adding labor and/or large investment costs that would take time to pay off in increased earnings. As a result, we have ended up with a “tragedy of the commons” where wages have been squeezed for years, so consumers have not been able to increase spending unless they borrow money, increasing debt. As a result, total revenues are growing very slowly, so companies have to focus on cost-cutting and share buybacks to increase earnings and earnings per share.

There isn’t much the central banks can do to change that dynamic.

Moreover, the fetishistic repetition of “government debt good, private debt b-a-a-a-d-d-d-d” is without theoretical or empirical support.

Total debt load is what drags economies down into “no groaf” mode, regardless of how frantically central banksters jiggle the lever for more food pellets with their furry little paws.

Well the government can always print to resolve its debt. You and I can’t. That makes them rather different. Actually, completely different.

Under current laws, the government can’t just print money (or create it digitally). When new money is created, treasury notes or bonds must be issued. That means that the government owes money to the people who buy the notes or bonds. So when the government resolves its debt, it creates new debt, and nothing changes.

Those notes created are readily exchanged for money, are fungible, and are thus money. Interest bearing money.

But the issuance of them does not resolve any debt.

Under currently law the US government can mint a trillion dollar platinum coin without any corresponding increase in debt.

The legality of the hypothetical trillioin dollar platinum coin is very controversial — maybe it’s legal, and maybe not. Four years ago, a lot of ink was spilled over this idea. Here’s a summary by Joe Firestone of some of the ideas:

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2013/01/trillion-dollar-coin-posts-on-legality-and-constitutionality.html

A portion of an article by Edmund Moy:

https://www.cnbc.com/id/100364183

It’s a gray area, but I don’t think it’s feasible.

Private debt is periodically completely removed from the economy, plus additional money that wasn’t privately issued; i.e. government debt. Government debt *pays* private debt. Further, government debt never has to be paid back at all. This means it can continue to support the assets created with it and be engaged in more production or support people’s savings desires. Private debt is never allowed to do that. Without public debt, no one can save. All of these factors make public debt a much better deal than private debt, by a long shot. Theoretically, with enough safe public debt supporting economic activity, most private debt would never even come into existence. Before the 70s, consumer debt was quite rare. So, on the whole, yeah: public debt good, private debt bad. There really isn’t much downside to it. As near as I can tell, only the rentiers feel any pain from it.

It was central banks that assigned themselves the job of managing the economy post crisis. In fact, they’ve engaged in pretty aggressive mission creep. Did the Fed say there should be more stimulus in 2009, when weighing in would have overcome the supposed political resistance that Summers claimed existed? Plenty of orthodox economists have written about how the Fed has been engaged post crisis in trying to use monetary policy as a stand-in for fiscal policy and how that’s failed.

And we’ve also written at length at how the Fed quit a long time ago being politically independent, so that pretense is no excuse for saying, “Not our job, the Administration and Congress need to carry the ball.”

Many financial sites have pointed out that continued QE by ECB and the BoJ have taken up for the Fed, since they’ve had the effect of keeping financial asset prices high, so the Fed hasn’t needed to do more. With 1/4 of the world in negative or near negative interest rate territory, Treasuries look like a mighty attractive investment. High bond prices = lower rates.

Plus your point about the Fed post 2014 is not relevant to the argument the author is making.

It seems like every time I turn around the Fed is out there making public statements and testifying before Congress that more government spending is bad and would cause scary wage inflation. Besides being flat wrong, the Fed’s prescriptions are an odious interference in the political process.

2 points:

http://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-jobs-day-2017-8

https://mishtalk.com/2017/08/04/july-part-time-work-jumps-by-393000-full-time-employment-down-54000/

=============================

Does the Fed Reserve really believe that we are at full employment???

Modern life has more and more become an avalanche of bullsh*t…

Let’s face it, the Fed has no reason to want to decrease unemployment. On the contrary, their mission is to keep unemployment from going down below a certain level where it will cause wage inflation. In the meantime, they’re inflating prices of all assets – stocks, real estate, commodities, etc. because they’re working for the FIRE sector and Finance, Insurance and Real Estate have been the major beneficiaries of the QE and ZIRP policies.

Team Obama re-inflated the 401(K), pension and real estate because the majority of the US population (except the poor) would be pleased and Obama would then coast to a re-election victory.

Capital Intensive business follows the cost of money intensely.

So while Wall Street speculates with cheap money, Dams, Bridges, Power plants, get built, looking at 10-20 year horizons.

We have lots of green energy because money is cheap. They raised interest rates half a point and two nukes were cancelled. This is not a coincidence.

Behind the scenes I think the switch to digitial currency by the US government is already being planned. Check out this interview starting at the 18 minute mark- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0VfCrIRoOaY&t=2121s

and for a robust macro view on bitcoin and a new financial paradigm see this interview of Simon Dixon, who is currently touring China with Jim Rogers and who I feel is simply brilliant- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cLt-5MqqfWU

If I were CEO of an insolvent tbtf bank I’d love digital currency. All those new opportunities for fees. And what better way to prevent a bank run? Not that I’m foily.

Ha, if you want to go down that route, the US government abandoned cash long ago. We stopped making high denomination notes in the 1940s, nearly 70 years ago(!). MICR (large scale machine reading of checks) had replaced cash by the 1950s. Most Americans alive today have never lived in an economy that was based on cash. Student loans, home mortgages, auto loans, healthcare bills: these are all digital, and have been for decades.

But I would disagree if you are arguing that bitcoin specifically is going to replace digital dollars. Why? What purpose does it serve government to do so? The current system works great.

I’m actually working on a project for my masters that uses visualizations to explain why the Fed acted the way they did post Great Recession, how it effected markets, and how it failed to help the broader economy (basically a crash course designed for near anyone to pick up and get the picture quickly). It’s definitely nice to see a lot of the components we are using in this article in some form of another.

That sounds cool. Do share it when you are done.

Adam, you might find this short animation useful in terms of the potential economic implications of future fiscal policy decisions that might deviate from continued adherence to the loanable funds theory, the Phillips curve hypothesis, and current Fed monetary policy strictures. Barry Ritholtz yesterday linked to a clever short animation by Paul McCulley & David McWilliams titled “The Coming War Between Trump & The Fed”. (Link: http://ritholtz.com/2017/08/coming-war-trump-fed/)

Salient points begin at about the 2 minute point of the 8 minute clip.

Just a thought. I’m not an economist, but I too would like to see your work product when you’re finished. Thanks.

If it’s not a complete visual eyesore, I will definitely share it.

Adam,

I have written a long essay on the monetary system and it is being used as a reading assignment in graduate schools at three of the world’s elite universities. You may want to take a look at it. Also a former head of one the world’s most important central banks read it and had this response to it.

“Despite the travels, I have read your essay “Monetary Madness”. I much enjoyed it. Your essay deserves to be widely read and is extremely well written. It contains little with which I would disagree and my comments below are more by way of nuanced reactions rather than basic disagreements…………Your concluding section is both powerful and persuasive.”

Here is a link to the paper on the website Medium. Unfortunately it is long at 55 pages so it takes a couple of hours of commitment.

https://medium.com/@RobertNYC/monetary-madness-438836c44464

If you care to discuss you can find me on LinkedIn.

RE: The main question: “So, now what? Should we abolish central banks?”

Why not? If a quack doc keeps making dumb mistakes, do you just let him keep trying with the poor cows? Or dump ALL the quack economists and start over?

Isn’t this supply side economics? That was indeed debunked. Did they stop calling it that so they could keep doing it?

Fed needs to understand all they have is a rope. They can pull the economy back from the edge of exploding in a mega bubble, but they can’t push businesses to lend when there isn’t demand.

And if they keep pushing that rope at some point there will be enough slack for them to hang themselves. Maybe it is a few more recessions away, but Fed omniscience isn’t permanent.

The Great Depression created the ABCT purge. That’s what lead to the Golden Era in U.S. economics (where voluntary savings were put back to work). So take the “Marshmallow Test”: (1) banks create new money, and incongruously (2) banks loan out the savings that are placed with them.

All savings originate within the framework of the commercial banking system. Saver-holders never transfer their funds outside the payment’s system (unless they hoard currency or convert to other national currencies). But the only way to activate savings is for their owners to invest/spend directly, or indirectly via a non-bank conduit. This is the sole source of both stagflation, c. 1965, and secular strangulation, c. 1980 (the impoundment and ensconcing of savings).

The solution is to drive the commercial banks out of the savings business, where the DFIs and NBFI (the DFI’s customers) have a symbiotic relationship.

Whether the pubic saves or dis-saves, chooses to hold their savings in the DFIs, or to transfer them to a NBFI, will not, per se, alter the total assets or liabilities of the DFIs, nor alter the forms of these assets and liabilities.

I.e., money flowing through the non-banks never leaves the payment’s system. What would this do? It would make the DFIs and NBFIs more profitable. It would reverse the decline money velocity and raise R-gDp, or real incomes.

-Michel de Nostredame

Nikos Bourtzis’ reference: “The loanable funds doctrine extends the classical theory, which determined the interest rate solely by savings and investment, in that it adds bank credit.”

No, that is not the loanable funds theory. All bank-held savings are lost to both consumption and investment, indeed to any type of payment or expenditure. Why?

Because whenever the DFIs grant loans to, or purchase securities from, the non-bank public, they acquire title to earning assets by initially, the creation of an equal volume of new money (demand deposits) – somewhere in the payment’s system. I.e., contrary to all economists, commercial bank deposits are the result of lending, not the other way around.

Interest is the price of loans funds. The price of money is the reciprocal of the price level.

– -Michel de Nostredame

It is a confusion of stock vs. flow (Nobel Laureate Dr. Milton Friedman was “one-dimensionally confused”). He pontificated that: “I would (a) eliminate all restrictions on interest payments on deposits, (b) make reserve requirements the same for time and demand deposits”. Dec. 16, 1959. He was good at math, not economics.

So Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek had the Austrian Business cycle theory of mal-investment all wrong.

The remuneration of IBDDs induces non-bank dis-intermediation (an outflow of funds or negative cash flow). And the current level is illegal per the FSRRA of 2006. This destroys money (actually savings) velocity. The 1966 S&L credit crunch (where the term credit crunch was first coined) is the antecedent and paradigm.

– -Michel de Nostredame

As professor Lester V. Chandler originally theorized in 1961, viz., that in the beginning: “a shift from demand to time/savings accounts involves a decrease in the demand for money balances, and that this shift will be reflected in an offsetting increase in the velocity of money”. His conjecture was correct up until 1981 – up until the saturation of financial innovation for commercial bank deposit accounts (the widespread introduction of ATS, NOW, and MMDA bank deposits).

– -Michel de Nostredame

The expiration of the FDIC’s unlimited transaction deposit insurance is prima facie evidence, to wit:

I commented on 12-16-12, 01:50 PM #1 “We’re close to seeing the real power of OMOs. R-gDp is likely to accelerate earlier & faster than anyone now expects. The roc in M*Vt before any new stimulus is already above average. With low inflation (given some deficit resolution), Jan-Apr could be a zinger”

It is a delusion to think that the NBFIs attract deposits from the DFIs, as reserve credits tend to precede reserve debits – as evidenced by the existence of float.

The sui generis nature of the payment’s system, where the whole is not equal to the sum of its parts in the credit creation process is not a zero-sum game, one bank’s gain by attracting more “core” or “derivative” deposits, is less than the losses sustained by other banks in the system. The whole (the forest), is not the sum of its parts (the trees), in the money creating process. All time (savings) deposits are derived from demand deposits. The DFIs could continue to lend even if the non-bank public ceased to save altogether.

Since savings are not a source of loan funds for the banksters, they can’t expand the system by perversely attracting savings.

The 300 Ph.Ds. on the Fed’s technical/research staff don’t’ understand the difference between a debit and a credit (confuse money with liquid assets).

It’s a feature, not a bug

Interest is the price of loan-funds. The price of money is the reciprocal of the price level – as the deceleration of money velocity since 1981 aptly demonstrates.

Must have been hard up for material today. The kid actually thinks central banks are “lenders of last resort”. That is laugh out loud funny! What exactly is it they lend? Seriously who believes that non-sense anymore. That is a concept that hasn’t applied in decades.

And low interest rates have ginned up lots of borrowing, but not the right kind of borrowing. Corporate debt levels are at all time highs in the U.S.

In any case his general thesis is correct. Economies are buried under too much debt and you can’t stimulate an over indebted economy with more debt.

Must have been nice to asleep during the crisis. You somehow missed central banks bailing out banks by lending against collateral (the equity infusions like TARP were done by various state Treasury departments, not central banks). That is what “lender of the last resort” means. The central banks paved new territory by acting as “dealer of the last resort” as Perry Mehrling, a world expert on the role of central banks, has discussed at length.

Being dismissive when you are out of your depth is not a good look. It backfires.

Yves Smith doesn’t know a credit from a debit.

Lender of last resort? Not so. Bankrupt u Bernanke had it backwards. Whereas Paul Volcker’s discount rate was below market interest rates and used for profit, the discount rate was made a penalty rate on 1/2003 (a penalty rate is one where the Fed fights inflation – not deflation, which was what the GFC was all about). I.e., Walter Bagehot’s dictum didn’t apply to the GFC.

And remunerating IBDDs destroyed the non-banks. It is an apoplectic theoretical error where the size of the NBFIs proceeded to shrink by $6.2T, and the DFIs to be expanded (necessitated as a monetary offset), by $3.6T. This theoretical monetary policy blunder has prevented both the commercial paper market, and the repurchase agreements from recovering. See: George Selgin:

http://bit.ly/2skp62e

This cock-eyed policy (an un-necessary and un-equal competition between the DFIs and the NBFIs), produced the same result as when the FDIC and the BOG raised Reg. Q ceilings in Dec. , for uniquely, the commercial banksters (the thrifts, which back then were NBFIs, viz., the S&Ls, MSBs, and CUs, which since Roosevelt’s “Banking Act of 1933”, had remained unrestricted).

Perry G. Mehrling? Wrong. There are leakages in the sectorial balances approach, just like in National Income Accounting.

you are the one that is out of your depth and you completely misinterpret Perry Merhling. If you had read his book “The New Lombard Street” you would understand why. They acted as “dealer of last resort” and that is a big difference from “lender of last resort” which is precisely why he rephrased the classic line, but I guess the subtly escapes you. Merhling has a very sophisticated understanding of things. I have taken his course on COURSERA and read a couple of his books so I don’t need a lecture from you on how this stuff works. You can’t possibly argue that what they did really worked unless your sole criteria for success is saving a corrupt and flawed system. Monetary velocity has fallen though the floor, there is even more debt in the system and they saved the banks and the rich by blowing another asset bubble. All they did is kick the can down the road and the fundamental problems are still with us bigger an badder than ever. This will become clear when it blows up next which should be the end game.

In any case, what precisely did they lend? Please explain. It’s all an enormous accounting charade.

The whole modern system relies on deception and universal public ignorance to operate. And that is why we had a monetary disaster that continues with us to this day. Until they reform the international monetary architecture by putting some type of disciplinary anchor back in the system it will continue to be dysfunctional and deeply flawed. Gold, the SDR, Bancor; any of them could do the trick but until some discipline is restored to the system it will be a mess. Merhling would be the first to acknowledge this problem although I would love to know how we would address it. Maybe he will weigh in for us. Perry are you out there?

“Monetary velocity has fallen though the floor”

No, savings velocity, Vt, not Vi, fell through the floor. I am the Alpha and the Omega.

Diminishing market depth and a surge in volatility were both on display Oct. 15, when Treasuries experienced the biggest yield fluctuations in a quarter century in the absence of any concrete news. The swings were so unusual that officials from the New York Fed met the next day to try and figure out what actually happened”

From: Spencer (@hotmail.com)

Sent: Thu 9/18/14 12:42 PM

To: FRBoard-publicaffairs@… (frboard-publicaffairs@frb.gov)

Dr. Yellen:

Rates-of-change (roc’s) in money flows (our “means-of-payment” money times its transactions rate-of-turnover) approximate roc’s in gDp (proxy for all transactions in Irving Fisher’s “equation of exchange”).

The roc in M*Vt (proxy for real-output), falls 8 percentage points in 2 weeks. This is set up exactly like the 5/6/2010 flash crash (which I predicted 6 months in advance and within 1 day).

I also predicted the 5/6/2010 “flash crash” (which denigrated statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s “Black Swan” theory.

To: anderson@stls.frb.org

Subject: As the economy will shortly change, I wanted to show this to you again – forecast:

Date: Wed, 24 Mar 2010 17:22:50 -0500

Dr. Anderson:

It’s my discovery. Contrary to economic theory and Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman, monetary lags are not “long & variable”. The lags for monetary flows (MVt), i.e., the proxies for (1) real-growth, and for (2) inflation indices, are historically, always, fixed in length.

Assuming no quick countervailing stimulus:

2010

jan….. 0.54…. 0.25 top

feb….. 0.50…. 0.10

mar…. 0.54…. 0.08

apr….. 0.46…. 0.09 top

may…. 0.41…. 0.01 stocks fall

Should see shortly. Stock market makes a double top in Jan & Apr. Then real-output falls from (9) to (1) from Apr to May. Recent history indicates that this will be a marked, short, one month drop, in rate-of-change for real-output (-8). So stocks follow the economy down.

And:

flow5 Message #10 – 05/03/10 07:30 PM

The markets usually turn (pivot) on May 5th (+ or – 1 day).

I.e., the May 6th “flash crash”, viz., the second-largest intraday point swing (difference between intraday high and intraday low) up to that point, at 1,010.14 points.

No, it is indeed you who do not know what you are talking about. And as far as Mehrling is concerned, he’s had me lecture at his course and speak at INET.

You have repeatedly straw manned me to cover for your misrepresentations. The “lender of the last resort” is the central banks’ duty to act as a bankers’ bank (if you actually read Mehrling, you’ll know he talks about the conflict between the role of central banks as bankers’ banks and as providers of financing for wars) and step in and lend to bank when they stop lending to each other, as happens during bank runs, when the failure of one bank leads banks to doubt the solvency of others, since (among other things) the failed bank will have defaulted on payments to customers of other banks, which means they could default on obligations to those other banks. Plus when one bank fails, customers also start pulling deposits out of banks and hoarding cash. You ought to know that but your denial of the “lender of the last resort” role the Fed and other central banks played says not.

You also ought to know that the Fed’s extraordinary assistance to banks was all structured as lending facilities, under their Section 13.3 powers. Did you miss that Goldman and JP Morgan had to become banks to get Fed support? Where were you when that happened? As the Minneapolis Fed summarized it:

Former central banker Willem Buiter said this provision meant the Fed could lend against a dead dog if it wanted to. And in case you missed it, even the bailout of Bear Stearns, which was essentially a bailout of the CDS market, was structured as a loan. I was writing about this in detail in real time yet years afterwards you make it clear you either didn’t understand it or so hate the Fed that you deny that they operated in line with the role they are supposed to serve. The issue, as I’ve long said, isn’t that they acted as lender of the last resort, it’s 1. That they went beyond that (see below), 2. They did nothing for the real economy (contra the Depression) while their mission creep basically took the heat off the Administration (and worse, Bernanke spoke against deficit spending repeatedly which was using his bully pulpit, which the Fed is not supposed to use, to bad ends) 3. As regulators, they did nothing to sanction bankers nor did they support anyone else sanctioning banker (specifically sending them t jail but even firing execs and board members would have been better than nothing) and 4. Did not lay out and back real reforms.

As for the dealer of the last resort, I mentioned that to show that the Fed has expanded its role beyond lender of the last resort. What do you think its new reverse repo program is all about? That’s one of its main purposes.

I never praised what the Fed did. I’ve been a long-standing critic, before, during, and after the crisis, and more recently, of their super low rates, which BTW are a completely separate matter than the Fed or other central bankers stepping in in a crisis. Just as one of many examples, I wrote repeatedly during the crisis that the Bagehot rule was to lend on a short term basis against good collateral to deal with liquidity crises, not solvency crises, and that the crisis was a solvency crisis.

So yes, you are out of your depth and saying your read a book that you at best cherry picked doesn’t change that. In addition, you’ve repeatedly straw manned me and made clear you didn’t understand or choose to misrepresent what the Fed did during the crisis to win an argument you are losing and defend the nasty and inaccurate attack you made against a writer. These are all violations of our written site Policies.

Mosler argues that QE is contractionary, since interest bearing assets are swapped for non-interest bearing. The interest income is thus removed from the private sector.

Mosler also thinks issuing government bonds is a monetary drain tightening as well. It would be if they hoarded the reserves from borrowing but of course they don’t. No idea why he says some of the things he says and it’s probably why he has to self publish his stuff, nobody listens to him.

This “mistaken” policy by the central banks is indeed intentional. Vast amounts of cash are inserted into the economy, not to stimulate the economy and increase the velocity of the money supply, but to inflate asset prices. The increased asset prices then become collateral for more borrowing by the economic and political elites. The money supply is increased many times over. All of this cash goes to the politically connected and is used to speculate on, yes asset & commodity prices, driving them up again in a corrupt cycle that has allowed the beneficiaries to accumulate incredible wealth, buy politicians and completely control the political economy for the benefit of their small privileged class who now live in incredible luxury while it is austerity for the rest of us.

Very little of this cash is invested in infrastructure or production, other than luxury villas and yachts and of course fine art. Instead of investing in productive enterprises, productive enterprises are bought and burdened with with debt, employment cut, pensions looted assets stripped. The speculators acquire great fortunes and the economy is looted. This is predatory capitalism at its worst. All this began in the 80’s under the supervision of Al Greenspan and the idiot Ronald Reagan, who should have been arrested long ago and tried for crimes against humanity, instead of being venerated.

Eventually, using the endless counterfeiting of fiat currency these elites and their descendants will own everything and genocidal policies like mass incarceration, distribution of powerful opiates and endless war with incredibly destructive weaponry used to eliminate the surplus population. The new Feudalism will then be established for generations.

An important step in stopping these criminal enterprises is to recognize that the architects of this system the entire political and financial community are not merely mistaken, they are criminal master minds that have pulled off the greatest rip-off in all history, turned the US into a colony for their greed, avarice and hatred for the common man. They need to be arrested and held accountable. Unfortunately they have infested the entire criminal justice system, set up a draconian surveillance system so that they can murder and loot with impunity.

Unfortunately until the passive population will be “awoke”, get out from in front of their television sets and Facebook pages, stop fighting each other, and demand that these criminal institutions be dismantled, they are condemning their descendants to extinction.

Since the entire criminal justice system and political class is in on the scam, what is needed is a tribunal of the people to institute unofficial trials to prosecute crimes against humanity and war crimes, to make the case against these thieves and mass murderers, to make public their crimes in minute detail and to demand justice. The time for this is now, the fate of the human race and our planet are at stake.

Ptolemy Philopater: Exactly. The significant economic purposes for which a debt was contracted, and the manner in which it is financed, determines its potential economic payback.

For example, if the debt was acquired to finance the acquisition of a (1) (new-security), the proceeds of which are used to finance plant and equipment expansion, or the construction of a new house, rather than the purchase of an (2) (existing-security) to finance the purchase of an existing house (read bailout), or to finance (1) (inventory-expansion), rather than refinance (2) (existing-inventories).

The former types of investment (1) are designated as “real” (new), as contrasted to the latter (2), which constitute “financial” (existing) investment.

Financial investment provides a relatively insignificant demand for labor and materials and in some instances the over-all effects may actually be retarding to the economy.

Compared to real investment, it is rather inconsequential as a contributor to employment and production. Only debt growing out of real investment, or consumption, makes an actual direct demand for labor and materials.

There is a widespread tendency for savings to be dissipated in financial investment or impounded in idle savings.

Ptolemy, you made me laugh because you are right. It is basically the greatest crime in human history. Yet most people are bamboozled by what happened. All this intellectual talk about the Taylor rule, the Phillips curve, QE, ZIRP, NIRP, etc just distracts from the underlying issues. If you focus on “first principles” it becomes pretty clear how this works and what happened. My only difference of opinion with you is if this was all some orchestrated scam or a crime of ignorance. I lean towards the latter but plenty of people think it was the former.

Sadly, you’re so right and we need to do something NOW.

Can we bring a new “modern” Madam Lefarge to the present time??

Yves response above and your comment make me feel I’m not the only “angry” person in the world!

I fear that not much change will be made unless blood again runs in the streets.

Unfortunately that is the story of history….too many believe that just “peaceful protest” will result in the changes and the discipline needed to renew our political system or obstructing perpetual war and the continuing financial raping of this country.

Since the 1980’s (probably shortly before under Carter) the rules of the financial game in the US have been trashed, the “umpires” (regulatory agencies) have been reduced to nil; the “monster” of so-called “free market capitalism” has been unleashed and the results are murderous.

“We” have sold our souls to the company store.

And, we will be evicted because we cannot pay the rent.

To stick with the theme of the site article, I do believe the establishment and the existence of the FED is needed. But, I must emphasize I believe the FED acted outside it’s oversight during and after the GFC

Non of this is going to end well.

The Bowery Boys’ MMT (Warren Mosler, L. Randall Wray, Bill Mitchell, Scott Fullwiler, etc. – don’t know a debit from a credit either).

First International Conference of Modern Monetary Theory (the Bowery Boys) Organizers: Stephanie Kelton | Scott Fullwiler | Randall Wray

http://bit.ly/2vBGfDR

Among the many problems during the GFC was that there was no Treasury-Federal Reserve collaboration. Effective monetary management is impossible without the cooperation of the U.S. Treasury. Treasury Secretary Jack Lew: “Treasury’s decisions about how to manage government debt are made independently of the Fed’s monetary policy choices, he said”. Thus there was a shortage of “safe-assets” necessitating the Treasury Supplementary Financing Program -SFP), etc.

I find Ellen Brown’s agenda more attractive.

Don’t know Ellen Brown but Richard Koo’s analysis of the Japanese crisis of the early 1990s if very informative. Japan launched a massive fiscal stimulus in the early 1990s in response their banking crisis. The fiscal stimulus was evidently enormous and enough to offset the drop in private sector demand associated with the downturn. It was only much later that Japan started playing monetary games. Seems to me that was the better approach, as monetary stimulus in the form of QE has no bearing on the real economy, it just stuffs money into asset markets. A well designed fiscal stimulus is more equitable and feeds the real economy.

Yes, QE is just an asset swap (cash for bonds). The effect is to lower long term interest rates, and in the case of how the Fed did it, also to lower mortgage spreads. There was a stimulus of sorts due to all the refis by homeowners…which by definition had to be ones in pretty good credit shape and therefore probably didn’t have the greatest propensity to spend. The Fed no doubt convinced itself that making mortgages cheap would set off another (strong) housing led- business cycle. They didn’t bother troubling themselves with pesky details like high levels of unemployment and student debt among the young, resulting low household formation, and short job tenures, which make mortgages a way riskier bet than in the past.

I don’t mean to quibble with you, but is it really an asset swap or is it better described as an asset transformation. From the persecutive of the central bank, it doesn’t really have any assets to swap as in they take in some asset and give out another asset. I understand that it looks like an asset swap from the view of the bank/private sector balance sheets, but we could just as easily call that an asset transformation. The CB takes in government bonds and in their place give out a liability claims in the form of central bank reserves. They do not take in some asset and give out another asset from their balance sheet. It seems to be that nothing was really “swapped”. Government debt was just cleverly rebranded as reserves, i.e. money. One could argue that is just semantics, but I think there is an important and subtle distinction here.

I also noted that you were arguing with one of the commenters elsewhere about whether a central bank is a “lender of last resort”. Not really interested in stepping into the middle of that spat as it looked to be a bit heated, but I thought the commenter raised an interesting point. When you look back to what “lender of last resort” meant in the past it doesn’t seem to mean the same thing now. I need to think about it a bit, but I am not sure it is accurate to describe what they do today as lender of last resort regardless of the tendency to describe it that way. When you walk through the mechanics and debits and credits of what that meant then and what it means now there is a pretty big disconnect. They aren’t really lending anything as discussed in the paragraph above in contrast to what went on back when Bagehot wrote his classic work. This stuff gets a bit tricky semantically and conceptually. Or maybe we use the same terminology, but are basically describing two different things which leads to confusion.

I agree with you points about driving down mortgage rates and all the rest but I would argue that the affect was even broader in impact. By putting so much new money in the system they drove down yields on virtually everything as all that new money sought a home. Technically the money gets “swapped” for interest bearing debt or under my proposed phrasing interests bearing debt gets “transformed” into money. Regardless of how we describe it, there is lots of new money in the system in search of yield. It may have been linked to debt instruments, but there is nothing to stop it from sloshing into all asset classes. Again this isn’t to argue your point which I think is accurate, just to suggest it is even more far reaching than mortgages.

2008 – “How did that happen?”

The early 1980s see the beginnings of financial liberalisation and the late 1980s sees the following crises, e.g. US S&L crisis; UK, Japan, Australia, Canada and Scandinavia real estate busts.

More financial deregulation leads to 2008; the Euro-zone crisis; Irish, Greek and Spanish real estate crashes.

2008 is just another real estate bust, leveraged up and transmitted internationally by complex financial instruments. As the global bust hits the Euro-zone, it crumbles.

Australia, Canada and Scandinavia are queuing up for their second real estate bust.

Today’s neoclassical economics was around in the 1920s and it led to the roaring 20s and the Great Depression. The roaring 20s, roared because of debt based consumption and debt based speculation. All the debt built up in the boom led to the debt deflation of the Great Depression.

Neoclassical economics was revamped but it still has its old problems.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

1929 and 2008 stick out like sore thumbs when you look in the right place.

The build up in the ratio of debt to GDP signals the build up of unproductive lending into the economy leading to a Minsky Moment (1929 and 2008).

Productive lending goes into business and industry.

Unproductive lending goes into real estate and financial speculation and it shows up in the graph above.

The UK:

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.53.09.png

We have a problem, a real estate fuelled economy driven by unproductive lending that naturally leads to financial instability.

Neoclassical economics doesn’t consider private debt in the economy and naturally leads to boom/bust capitalism because of this over-sight. It doesn’t even consider debt and so can’t make the finer distinction between productive and unproductive lending.

If you want financial stability, don’t use neoclassical economics.

What economics do Central Bankers use?

Neoclassical economics.

This is why the FED didn’t see 2008 and the S&L crisis as they were building.

As the debt-to-GDP ratio was screaming away to the Minsky Moment, the FED did nothing as financial regulations were relaxed even further.

1929, Japan 1989 and 2008 were all the same.

A debt saturated economy with a debt fuelled asset price bubble.

Richard Koo compares them and gives us some lessons we might learn.

He explained why austerity didn’t work in Greece to the IMF.

Ben Bernanke read his book and altered US policy.

Richard Koo leads those we follow.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

The West turned Japanese in 2008.

Our hopes for recovery need to adjust to Japanese timescales.

27 years and it’s still stagnating.

Koo talks debt. He should be talking income.

Debt and its repayments are the problem.

If you watch the video you’ll find out why.

If you knew anything about macro, and Koo, you’d know.

No such thing as a “Minsy Moment” – nor Nassim Nicholas Taleb black swan.

The graph of the US shows the tipping points in 1929 and 2008.

You could call them Minsky Moments, some people do.

I guess you can’t read. I predicted not only the contraction, but exactly when it will happen.

The fact is that all economists are wrong:

(1) Alan Blinder: “After the Music Stopped”

A. Bubble bursting is like that. At some unpredictable moment, investors start “looking down”…, realizing that the sky-high prices they believed would never end are not supported by the fundamental – and start selling. It is abundantly clear that the crash must come eventually. Fundamentals win out in the end. But why it happens just when it does is always a mystery.

B. No one will ever know…why the stock market crashed in October 1987, rather than September, or November.

(2) Alan Greenspan: “The Map and the Territory”

A. The wholly unprecedented stock price crash on 10/19/87…there was no simple probability distribution from which that event could be inferred

B. with rare exceptions it has proven impossible to identify the point at which a bubble will burst, but its emergence and development are visible in credit spreads

(3) Ben S. Bernanke: “The Courage to Act”

A. First, identifying a bubble is difficult until it actually pops.

B. A lack of transparency caused a loss of confidence.

(4) Janet Yellen’s speech: “A Minsky Melt Down”

A. “Minsky understood this dynamic He spoke of the paradox of deleveraging, in which precautions that may be smart for individuals and firms – and indeed essential to return the economy to normal state – nevertheless magnify the distress fot eh economy as a whole”

(5) Joseph E. Stiglitz “Free Fall”

A. Bubbles are, however, usually more than just an economic phenomenon. They are a social phenomenon.

B. Futures prices are unpredictable.

(6) Paul Krugman “End This Depression Now”

A. What actually happened, of course, was the Fed did everything Friedman said it should have done in the 1930’s – and so the economy seems trapped in a syndrome that, where not nearly as bad as the GD 1.0, bears a clear family resemblance.

(7) Noah Smith “Bloomberg View columnist.

A. All this adds up to a pessimistic conclusion — recessions just aren’t very predictable from economic data. The reason economists couldn’t foresee the Great Recession isn’t that they’re blinkered or closed-minded or arrogant or stupid — it’s because no one could predict it, at least not with the kind of macroeconomic data that now exist.

But even given the surrogate metric (Yellen’s “ligature marks” and Pimco Paul Allen McCulley’s “Minsky moments”), viz., RRs, we are cognizant of what predetermines the “seasonal factors” (the exogenous celestial pulse).

Just think, you could be paying Paul Tudor Jones 2.25% of funds and 25 percent of profits

No, that’s not what happened. Monetary flows contracted, were negative, for 29 contiguous months (the proxy for inflation). This turned otherwise “safe” or inflated unproductive assets, upside down/ under water. Then monetary flows fell, was negative (the proxy for real-output) during the 4th qtr. of 2008. All of this was both predictable and preventable:

POSTED: Dec 13 2007 06:55 PM |

The Commerce Department said retail sales in Oct 2007 increased by 1.2% over Oct 2006, & up a huge 6.3% from Nov 2006.

10/1/2007,,,,,,,-0.47,… -0.22 * temporary bottom

11/1/2007,,,,,,, 0.14,,,,,,, -0.18

12/1/2007,,,,,,, 0.44,,,,,,,-0.23

1/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.59,,,,,,, 0.06

2/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.45,,,,,,, 0.10

3/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.06,,,,,,, 0.04

4/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.04,,,,,,, 0.02

5/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.09,,,,,,, 0.04

6/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.20,,,,,,, 0.05

7/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.32,,,,,,, 0.10

8/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.15,,,,,,, 0.05

9/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.00,,,,,,, 0.13

10/1/2008,,,,,,, -0.20,,,,,,, 0.10 * possible recession

11/1/2008,,,,,,, -0.10,,,,,,, 0.00 * possible recession

12/1/2008,,,,,,, 0.10,,,,,,, -0.06 * possible recession

Trajectory as predicted:

Then Bankrupt u Bernanke introduced the payment of interest on IBDDs.

I think many central bankers fully understand that monetary policy alone only works in a normal, fairly well balanced economy that only has marginal problems that can be fixed with marginal changes.

When the economy falls into a depression where demand has become insufficient, then fiscal stimulus is necessary. However, if the parts of government that do fiscal stimulus refuse to do their job, then the central bank is left to apply the only tool that it has, weak though it may be under the circumstances.

“I think many central bankers fully understand that monetary policy alone only works in a normal, fairly well balanced economy that only has marginal problems that can be fixed with marginal changes.”

Huh? Monetary policy doesn’t work, that is why we go from crisis to crisis. Central bankers are to monetary policy and witch doctors are to medicine. Monetary policy is the source of our repeated boom bust cycles and until these guys reform their understanding of the system we will continue to suffer from crisis after crisis.

“one of the biggest outcomes (of monetary policy) has been corporate financial speculation: issuing debt to buy back their own shares”

Utter clarity in a sentence.

Exactly.

See:http://bit.ly/2v9MnFt

The Keynesian macro-economic persuasion that maintains a commercial bank is a financial intermediary [sic] results in increasing levels of bad debt.

See: “Hoenig, who was a high-ranking Federal Reserve official during the crisis, cautioned Senate Banking Committee Chairman Mike Crapo and the committee’s senior Democrat, Sherrod Brown, “against relaxing current capital requirements and allowing the largest banks to increase their already highly leveraged positions.”

Using public data to analyze the 10 largest bank holding companies, Hoenig found they will distribute more than 100 percent of the current year’s earnings to investors, which could have supported to $537 billion in new loans.

On an annualized basis they will distribute 99 percent of net income, he added.

He added that if banks kept their share buybacks, totaling $83 billion, then under current capital rules they could boost commercial and consumer loans by $741.5 billion.”

Any increase in bank capital destroys the money stock $ for $.

Because the economy keeps alternating between near-recessions (2012, 2015-16) and shallow rebounds this is no economic expansion. Together with the initial recovery period that only partially offset the enormous contraction of 2008-09, the economy has gone nowhere despite the passage of a decade since trouble first erupted monetarily.

Unfortunately, the latest GDP estimates and updates all merely confirm that through the middle of 2017 it isn’t likely to get somewhere anytime soon. The only aspect that seems to have changed is that in GDP terms the rebound this time after the near-recession quarters is considerably weaker and less convincing than the one in 2013-14. That would certainly fit curve comparisons from the UST yield curve to eurodollar futures and even WTI.

http://www.alhambrapartners.com/2017/07/28/gdp-and-revisions-confirms-the-curves/

I always thought the idea that low interest rates would “encourage” investment and lending was absurd. I took econ 101 in 1960, before the Mount Pelerin Society took over the economics world, and one of the lessons I was taught, which central bankers learned during the Depression, was, “You can’t push on a string.” Volcker showed in 1980 that interest rates can restrict investment and lending (and destroy unions, which was one of the goals of the DLC, later), but the converse is not true.

If you’re not reading stuff here, you’re missing the boat ==> Because the economy keeps alternating between near-recessions (2012, 2015-16) and shallow rebounds this is no economic expansion. Together with the initial recovery period that only partially offset the enormous contraction of 2008-09, the economy has gone nowhere despite the passage of a decade since trouble first erupted monetarily.

Unfortunately, the latest GDP estimates and updates all merely confirm that through the middle of 2017 it isn’t likely to get somewhere anytime soon. The only aspect that seems to have changed is that in GDP terms the rebound this time after the near-recession quarters is considerably weaker and less convincing than the one in 2013-14. That would certainly fit curve comparisons from the UST yield curve to eurodollar futures and even WTI.

http://www.alhambrapartners.com/2017/07/28/gdp-and-revisions-confirms-the-curves/

Wow! Why is the presented as a brand new insight? This has been thoroughly addressed for decades by monetary reformers (see the 2012 National Emergency Employment Defense Act HB2990, sponsored by Dennis Kucinich) and the American Monetary Institute (monetary.org) and Positive Money in the UK.