Lambert here: The author introduces the idea of “impersonal markets, where traders could directly trade without the need of an affiliation,” as enabled by new media like printing and the post, and as opposed to “networked and collective institutions like merchant guilds.” While the history lesson is interesting, it’s not clear to me how dominant “impersonal markets” really are. For example, today’s market for health care providers is not. Nor is the market for many other services, including those involving the sale of power or influence. We might draw an analogy between Janine Wedel’s flexians and guild networks, for example. We might also consider the Customer Reviews on Amazon an antidote to an overly impersonal e-commerce market.

By Prateek Raj, a PhD Candidate in Strategy and Entrepreneurship at University College London and a Research Associate at the Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State at University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Cross-posted from Evonomics.

In the sixteenth century, the Northwest European region of England and the Low Countries underwent transformational change. In this region, a bourgeois culture emerged and cities like Antwerp, Amsterdam, and London became centers of institutional and business innovation, whose accomplishments have influenced the modern world.

For example, one of the first permanent commodity bourses was established in Antwerp in 1531, the first stock exchange emerged in Amsterdam in 1602, and joint stock companies became a promising form of organizing business in London in the late sixteenth century. The sixteenth century transformation was followed by the seventeenth century Dutch Golden Age, and the eighteenth century English Industrial Revolution. What made the Northwest region of Europe so different? The question remains a central concern in social sciences, with scholars from diverse fields (Weber, 1905; North, 1990; Padgett and Powell, 2012; McCloskey, 2016; Rubin, 2017) researching the subject.

The Medieval Power of Merchant Guilds

Markets don’t function well if they are ridden with frictions like lack of information, lack of trust, or high transaction costs. In the presence of frictions, business is often conducted via relationships.

Until the end of the fifteenth century, impartial institutions like courts and police that serve all parties generally—so ubiquitous today in the developed world—weren’t well developed in Europe. In such a world without impartial institutions, trade often was (is) heavily dependent on relationships and conducted through networks like merchant guilds. Such relationship-based trade through dense networks of merchant guilds reduced concerns of information access and reliability. Not surprisingly, because the merchant guild system was an effective system in the absence of strong formal institutions, it sustained in Europe for several centuries. In developing countries like India, lacking in developed formal institutions, networked institutions like castes still play an important role in business.

Before the fourteenth century, merchant guild networks were probably less hierarchical, more voluntary, and more inclusive. But, with time, merchant guilds started to become exclusive monopolies, placing high barriers to entry for outsiders, and they began to resemble cartels with close involvement in local politics. There were two reasons why these guilds erected such tough barriers to entry:

- Repeated committed interaction was the key to effectiveness of merchant guilds. Uncommitted outsiders could behave opportunistically and undermine the reliability of the system. Therefore, outsiders faced restrictions.

- Outsiders threatened the position of existing businessmen by increasing competition. So, even genuinely committed outsiders could be restricted to enter as they threatened the domination of existing members.

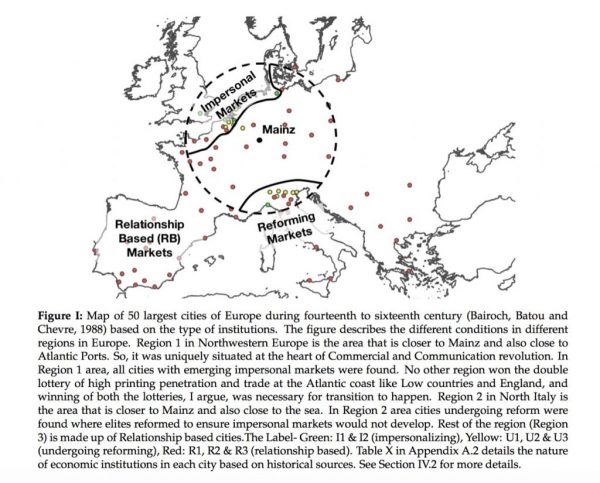

But, in the sixteenth century, the merchant guild system began to lose its significance as more impersonal markets, where traders could directly trade without the need of an affiliation, began to emerge (see Region 1 of map in Figure I) and rulers stopped granting privileges to merchant guilds. The traders began to rely less on networked and collective institutions like merchant guilds, and directly initiated partnerships with traders who they may not have known well. For example, in Antwerp the domination of intermediaries (called hostellers)who would connect foreign traders declined. Instead, the foreign traders began to conduct such trades directly with each other in facilities like bourses.

Emergence of Markets in the 16th Century

In a new working paper, I study the emergence of impersonal markets in Europe during the sixteenth century. I survey the 50 largest European cities during the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries (mapped in Figure I) and codify the nature of sixteenth century economic institutions in each of the cities (explore interactive data on early modern Europe). In the survey, I find that merchant guilds were declining in the Northwest region of Europe, while elsewhere in Europe they continued to dominate commerce until much later, although there were some reforms underway in the Milanese and Viennese regions of Italy.

What explains the observed pattern of emergence of impersonal markets in sixteenth century Europe? I focus on the interaction between the commercial and communication revolutions of the late fifteenth century Europe. In the paper, I argue that the Northwest European region uniquely benefited from both of these revolutions due to its unique geography.

Commercial Revolution at the Atlantic Coast

What motivated traders to seek risky opportunities beyond close networks? If traders found partnerships with unfamiliar traders beyond their business networks to be highly beneficial, that would provide good incentives for the rise of impersonal markets. The Northwest Region was close to the sea, notably the Atlantic coast, which was at the time undergoing a commercial revolution with the discovery of new sea routes to Asia and the Americas. So, the region became a hub for long distance trade, attracting unfamiliar traders who came to its coast looking for business opportunity. I find that all cities where merchant guild privileges declined were at the sea, along the Atlantic or North Sea coast. Moreover, all cities where merchant guilds underwent reform (but didn’t decline) were within 150km of a sea port.

The Communication Revolution of the Postal System and the Printing Press

What made traders feel confident about the reliability of such risky impersonal partnerships? If availability of trade-related information and business practices improved, it could increase confidence traders had in such unfamiliar partnerships. In the sixteenth century, the postal system improved across Europe. The postal system made communication between distant traders easier as traders could correspond regularly with each other and gain more accurate information. This helped expand long distance trade across Europe.

While the Northwest European region didn’t have a particular advantage over other regions in postal communication, it had an advantage in early diffusion of printed books. The Northwest European region was close to Mainz, the city where Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable time printing press in the mid fifteenth century. Dittmar (2011) showed how cities close to Mainz adopted printing sooner than many other regions of Europe in the first few decades of its introduction. So, trade-related books and new (or unknown) business practices like double-entry bookkeeping diffused early and rapidly in the region.

Such a high penetration of printed material reduced information barriers and improved business practices. I find that all cities where guild privileges declined or merchant guilds underwent reform in the sixteenth century enjoyed high penetration of printed material in the fifteenth century. Among cities within a 150km distance from a sea port, cities where merchant guilds declined or reformed had more than twice the number of diffused books per capita than cities where merchant guilds continued to dominate.

As a comparison, there were four major Atlantic port cities where merchant guilds declined: Hamburg, London, Antwerp, and Amsterdam; while there were four guild-based Atlantic cities: Lisbon, Seville, Rouen, and Bordeaux in the sixteenth century. The fifteenth century per capita printing penetration of the cities would stack as: Lisbon < Bordeaux < Hamburg < Seville < Rouen < London < Amsterdam < Antwerp.

The combination of both the commercial revolution along the sea coast, especially the Atlantic coast, and the communication revolution, especially near Mainz, uniquely benefited Northwest Europe, as it began to attract traders who favored impersonal market-based exchange over exchange conducted via guild networks. Rulers began to disfavor privileged monopolies when they realized the feasibility of impersonal exchange and that they could have superior sources of revenue from impersonal markets. In the region, trade democratized, as more people could participate in business.

Regions like Spain and Portugal that benefited only from the commercial revolution of trade through the sea to Asia and Americas had low levels of printing penetration. In contrast, regions like Germany, Italy, and France benefited from the communication and print revolution but didn’t enjoy a bustling Atlantic coast. Thus, no other region enjoyed the unique combination of both benefits of the commercial and communication revolution.

Takeaway for Policy Makers: Democratize the Market

If information access is poor (lack of transparency) or businesses don’t adopt reliable business practices (poor financial reporting or opaque quality standards), these deficiencies at the business level can make customers and investors question the reliability of new businesses. Politicians, like medieval rulers, may be more willing to enter into a nexus with dominant businesses, like medieval merchant guilds, if 1) market frictions or 2) lack of incentives make the economy dependent on such businesses.

This was the case with the taxi industry for a long time, where customers were willing to pay a high fee to get reliable taxi services as supply of drivers was low (new drivers in cities like London had to pay a high license fee and fulfill tough training requirements). But, better taxi hailing mobile apps like Lyft and Uber, by giving customers access to real time GPS tracking, have revolutionized the industry, much like the communication revolution did in late fifteenth and sixteenth century. Another area where information access has improved reliability in business is the tourism and travel industry.

While in the past the tourism sector was dominated by travel agents and their recommended offerings, now an influx of providers and travel comparison websites, such as expedia.com and AirBnB, has increased the reliability of small unknown hospitality service providers. Today, many prefer to stay at a stranger’s home over a reputed hotel chain. Such a revolution in the taxi or the travel industry is following the old historical trend where disruption in how information is made available changes how businesses are organized.