Yves here. Commentators and analysts tend to be black or white on the topic of corporate social responsibility. As CalPERS demonstrated in the 1990s, being an advocate for better governance and serving as an activist was a profitable strategy, enhanced CalPERS’ reputation, and was pro-investor generally, and so was a win on all fronts. At the same time, as our Jim Haygood likes to point out, its ill-timed decision to abandon tobacco stocks, near their bottom not long before the massive Federal-state settlement was hashed out, was a costly move. And one can argue more broadly that if one were to be rigorous about corporate social responsibility, there would be no one to invest in because just about no company is clean on all dimensions of CSR.

However, Olenick is making a narrower point. Large companies almost reflexively reject outside efforts to make them do things differently. However, demands that executives may be inclined to regard as mere overweening do-goodery may in fact reflect changing social priorities. The pollution example illustrates that if you don’t get on the bus, you will wind up under the bus. And more important, being attuned to these shifting demands and responding to them in a timely manner can be a profitable strategy.

By Michael Olenick, a research fellow at INSEAD. Originally published at his website

In 1970 a group of reformers led a campaign to “Tame G.M.” via a proxy battle that called for “social responsibility.”

The Harvard Crimson memorialized their demands. Quoting verbatim:

- changing GM new car warranties to give more guarantees that the automobile will work;

- improving health and safety standards for GM;

- asking GM to “substantially increase” the number of non-white new car dealerships. At present, there are seven non-white franchises out of GM’s total of 13,000 national dealerships;

- asking the company to meet Health, Education, and Welfare Department anti-pollution standards before the 1975 HEW deadline and to devote more research to study other pollutants in the environment;

- requiring GM to develop a car by 1974 that can crash into a wall at 60 m. p. h. with no injury to the occupants. The National Safety Bureau has already designed such a car that works at 47 m. p. h.;

- enlarge GM’s Board of Directors from 24 to 27 seats, adding three representatives of the public;

- change the GM charter to restrict the corporation to operations which are not “detrimental to the health, safety, or welfare of the citizens of the United States…”;

- set up a “shareholder’s committee” to study GM’s impact on the country, including an assessment of its efforts to produce pollution-free engines and safe cars, its effect on national transportation policy, and, in general, the manner in which it handles its economic power.

In response, to-be Nobel Laureate Milton Friedman — thought leader of the Chicago School of Economics — published a scathing article in the New York Times. I’ve already detailed the article and will not repeat the core criticisms except to focus on one … noncustomer demands balanced against shareholder value.

Friedman begrudgingly admits that “social responsibility” and business practices that eventually increase share price sometimes align. “… it may well be that in the long-run interest of a corporation that is a major employer in a small community to devote resources to providing amenities to that community… That may make it easier to attract desirable employees, it may reduce the wage bill or lessen losses…” He then goes on to label these moves “hypocritical window-dressing because it harms the foundations of a free society.” He backs off telling companies to avoid these moves because “that would be to call on them to exercise a ‘social responsibility!’”

Let’s think about a world where GM ignored Friedman and listened to the reformers.

In our mythical 1970’s GM, after expanding their Board of Directors, General Motors decides to focus on several key areas of competition:

-

- Quality & Reliability. Quickly realizing that the cheapest way to extend a warranty is to build more reliable cars, GM tasks their talented engineers with vastly improving reliability. Those engineers find a well regarded expert working in far-flung Japan, W. Edwards Deming, and convince him to come home and apply his methods — that were improving the quality of Japanese products — to GM plants.

- Safety. GM’s theoretical 1970 safety initiative finds that baby boomers, their largest up-and-coming customer group, prefer safer cars. There is a reason Ralph Nader’s book, “Unsafe At Any Speed,” became a bestseller. GM finds that safer cars cost slightly more to build but provide a competitive advantage and buyers are willing to pay considerably more.

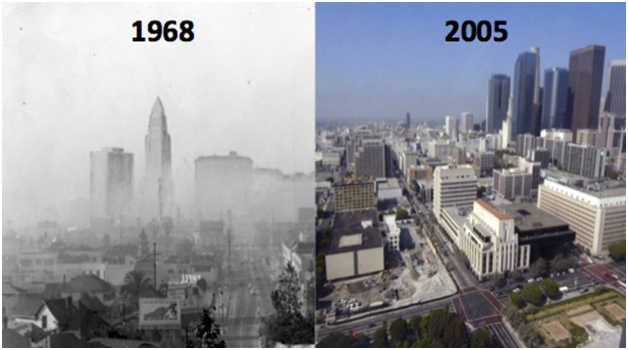

- Pollution. In 1970 American cities were choking with smog. Los Angeles was especially disgusting. Below is a photo of Los Angeles from that time and a more recent photo. Pollution was more than a social concern: it was a quality of life issue, a classic commons problem that Milton Friedman no doubt understood could not be solved with traditional market forces. GM’s early 1970 low-pollution cars sell well in car-crazed LA, a traditional trend setter that pushes them to the rest of the world.

- Diversity. GM makes an effort to train and launch dealerships with African American and Hispanic owners. They realize 7 out of 13,000 minority-owned dealerships, .054%, is ludicrously low. GM quickly realizes dealerships owned by African-Americans, staffed by non-racist salespeople, are more likely to be frequented by African-Americans. They sell more cars. Dealerships owned by Hispanic Americans hire Spanish and English speaking salespeople: they also sell more cars.

Every one of these “social responsibilities” that Friedman — and, by extension, followers of Shareholder Value Theory — rail against were, in hindsight, likely moneymakers. The inverse is also true; GM ignored these areas and their business was decimated by Japanese and German automakers.

Friedman’s assertion that “social responsibility” for businesses is nonsense is, in itself, nonsense. Despite that Friedman’s view became and, in large part remains, a dominant view it is simply wrong. In hindsight, had GM adopted these demands the business, and the shareholders, would have been healthier and wealthier. There is oftentimes no genuine conflict between shareholder value and social responsibility. Indeed, the opposite can be true: better managed businesses understand that fulfilling social responsibility can increase shareholder value.

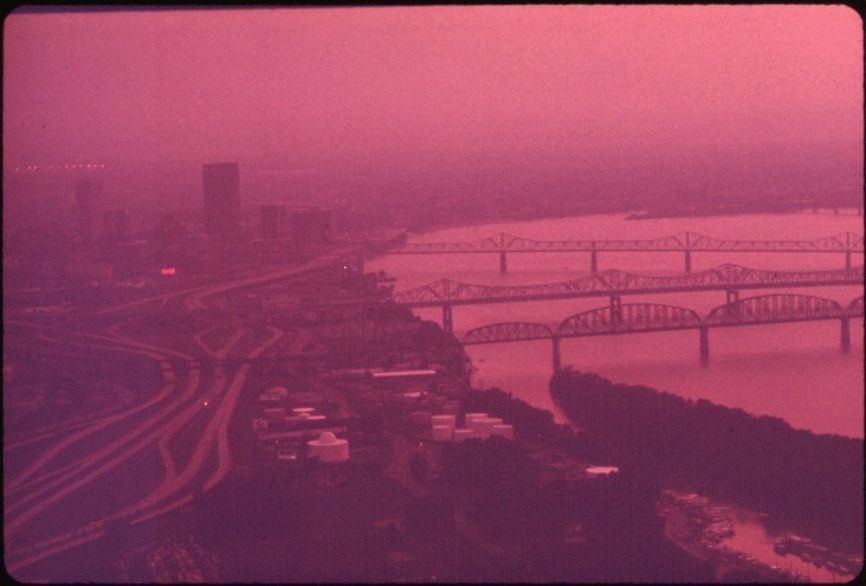

Here are some other photos of smog from the time Milton Friedman argued there was no value, nor market, in cars that polluted less.

Manhattan:

Louisville:

My god, why is Milton Friedman still quoted? Remember how the economy of Iceland was a banking ponzi scheme that blew up a few years ago and they famously jailed their bankers and did not put the public on the hook for the bank’s private debts worth billions? They got themselves in this fix because that made the enormous bad mistake of following Milton Friedman’s advice in how they should organize their economy years earlier.

He even went to the place back in ’84 (http://www.progressive-economics.ca/2008/10/14/milton-and-the-meltdown-in-iceland/) to put his stamp of authority on how to follow his theories to remake their economy. I wonder what would have happen if over the past few decades people would have listened to his careful advice – and then done the opposite?

As for the Chicago School of Economics where he had his lair, I have said it before and I will say it again. They should take off and nuke the site from orbit – it’s the only way to be sure!

They didn’t make the “mistake” of following, they chose to (pretend to) believe him over everyone else, and over common sense / historical data. I’m sure there were a few saps who actually “believed” him, but they weren’t the ones who started pushing the notion. It was just a case of professionals wanting their GNP numbers to grow, deciding that their peers’ (in banking) idea about doing it that way was as good a way as any, and their then looking for “academic support”.

Why is Friedman still quoted? Because it’s in the financial interest of numerous professors, lawyers, and journalists to do so. The Koch brothers and their billionaire allies spend huge sums of money subsidizing the doctrines of Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, and James Buchanan (not the 15th U.S. President). People keep reading and hearing good things about these ideas, and after a while, it’s hard not to be a believer. It’s like attending church Sunday after Sunday after Sunday — the ideas get reinforced in people’s minds.

This post is about 20 years behind the times.

The war was won and now it’s about managing the peace.

Social responsibility has gone mainstream. It’s corporate business as usual nowdays. So called ESG Investing — Environmental, Social and Governance — is big business. Companies now have social responsibility PR efforts, put out sustainability reports, and bow deeply at the Social Responsibility shrine. Really.

In the early days it was deeply committed religious and other ethically driven investors working almost on their own for reasons of spirit, ethics, virtue, values, etc. Then it grew. And then it became profitable. And now it’s huge driven by money and profit. The danger now is that it’s so formulaic and so mainstream it degenerates into handwaiving and “green-washing” — i.e. Doo-Goodery data and PR flim flam that has no corporate soul and that soaks up capital for so-called socially responsible management by tugging on investors heart strings in a process of Hegelian dialectical transformation where things become their opposites..

There are still many companies that believe it’s all nonsense. Or that pay lip service but do not integrate social responsibility into everyday thinking and operations at a substantive level. Even GM, way back when, did form a committee to think about these issues but they did not change their core businesses. Those changes to the core are what I’m referring to, not forming a committee or small donations to a charity. Doing the right thing socially can, and in the case of GM would have, also made more money than doing the wrong thing.

This article was inspired after a study I worked on related to stock buybacks showing that, in excess, they cause the value of businesses to fall. I was debating with a proponent of buybacks who said they’re necessary and right under shareholder value theory, which remains alive and well. Shareholder value theory (like my post a couple days ago says) comes from Milton Friedman’s article. I realized most people hadn’t read it and neither realized nor knew Friedman was telling GM to commit industrial suicide to avoid being socially responsible.

I quite agree with a lot of what you’re saying. But there’s a tautologically circular quality to these debates.

The contemporary corporate responsibility crowd says it enhances long-term shareholder value. So they don’t disagree in principle with shareholder value theory, they simply say social responsibility is more efficient than irresponsibility at raising the stock price. They probably do have a point. I won’t cynically argue against it.

But it gets a bit like the early Christians who let the heathen have their holidays by naming them after Saints. They expanded the realms of Christiandom. But whether the messages of the Gospel were also expanded, well?? LOL

I’m curious about where the power centers in a corporation actually are. My impression is that even organized shareholders are treated with contempt. Directors often are patted on the head by top management, who really is in charge and very hierarchical and dictatorial. Therefore,the shareholder value theory is horse manure. They’re not running it for the shareholders. If anything, they’re boosting share price to get more investors, but that’s just one among many business objectives. It should the CEO career enhancement theory.

” It should the CEO career enhancement theory.”

Also the CEO ginormous pay theory. ;)

Friedman pushed bs shareholder value theory; too many corporations bought into the ‘dream’; ended up in Galt’s Gulch wrecking the real economy; and Atlas shrugged.

Thanks for this post.

Shareholder value is alive and well only in that most executive pay package compensations are now mostly stock options creating great incentive to boost stock price over the underlying bossiness, well covered here on NC. This was due to unintended consequences of Bill Clinton’s attempt at corporate pay reform.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2006-11-26/how-bill-clinton-helped-boost-ceo-pay

I’m with the author in principle, but much of the reduction in pollution has to come from offshoring manufacturing. It would be a stronger article if the author dug up some numbers on what percentage of the smog reduction came from cleaning up car exhaust.

My mom, back in the 70’s when nearly everyone was still buying nothing but domestics, bought a Volvo sedan. Despite the costs, and mechanics who worked on imports being a rarity then, she bought it because the Volvo’s were safer than the domestics on the road in that era.

Shareholders will exploit workers just as effectively as executives do. We need a labor theory of value — workers should control the shares of each company, not vultures, rent extractors, and coupon clippers. There should be zero return on investment, outside of the value created and retained by the workers.