By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She now spends much of her time in Asia and is currently working on a book about textile artisans.

The $3 trillion global fashion industry is second only to the oil industry in its pernicious impact on the environment.

The red hot, growing fast fashion industry– which produces cheap, disposable clothes, sometimes for a single use– only worsens the industry’s environmental impact, by generating huge amount of textile waste. US consumers typically each toss out eighty pounds of textiles per year, while those in the UK, on average, 350,000 tonnes of used clothing ends up in landfills annually (as I discussed in this post, The High Hidden Costs of Fast Fashion).

Forbes has just published a ridiculously upbeat assessment of this problem, its headline clearly spelling out its thesis: Why India and China May Be The Solution To The World’s Fast Fashion Crisis.

Forbes rests much of the argument on two observations. First, emerging market consumers, when surveyed, place greater emphasis on sustainability compared to those in mature markets. This is particularly true for respondents from India and China, which together, account for more than a quarter the global population:

The State of Fashion 2017 report, citing Global Lifestyle Monitor, reveals that 65% of consumers in emerging markets actively seek out sustainable fashion versus 32% or less in mature markets , a finding backed up by Mastercard’s 2015 Ethical Shopping Survey. Coming in at 78% of respondents for India and 65% for China, sustainability is by and large a key consideration for consumers in these two hotspots.

And second, these emerging market consumers currently consume less textiles than do consumers in more developed countries. Forbes again:

Even where sales grew eight times faster (in developing countries like Brazil, China, India, Mexico and Russia) consumers are still more reserved in their spending than their developed market counterparts. “Even after this increase, the average developing-country resident purchases a fraction of the clothing that his or her developed-world counterpart buys each year,”McKinsey reports.

Now, I admit, there’s an attractiveness to this thesis. I don’t know very much about China, although I have visited several times.

But I do know a bit about India– which has a very different attitude toward waste than prevails in the US (as I’ve previously discussed in this post, Waste Not, Want Not: Right to Repair Laws on Agenda in Some States. Wasting food is considered to be sinful, a healthy repair culture flourishes, and items are typically reused and repurposed– including used clothing, which is either handed down, or often made into quilts such as kantha, the celebrated stitch painting of Bengal (see this luscious exhibition catalogue, Kantha: The Embroidered Quilts of Bengal).

In fashion area, India still maintains a certain separateness. To be sure, global brands are present, some are thriving, and demand for them is increasing– particularly among younger city residents. Yet overall, Indian producers of traditional textiles are also flourishing. Indian women, for example, still wear saris– particularly for more formal occasions– or basic salwar kameez– the far-more-attractive and climate appropriate version of Hillary’s pant suits. And what Indian male politician would be willing to surrender his Nehru jacket– the ubiquitous uniform throughout the country for politicians? India has for millennia, led the world in producing the finest quality textiles, and people retain an awareness of, and appreciation for quality. Tailoring is still widely available, and reasonably priced, so clothing fits (which is by no means the norm in the US and many parts of Europe, as discussed in What If Clothes Were Made to Fit Bodies?)

Unfortunately, as much as I’d like to hope that consumers in emerging markets might herald a shift away from the current destructive, wasteful patterns, I have several concerns with the Forbes thesis.

My first concern, as with other similar arguments– e.g., millennials consume fewer goods and appreciate sustainability more– that are based in an expected shift in who is consuming, that still leaves us very much with the status quo, whereby consumers consume, and waste, too many textiles in the present day.

To follow on from that, there is a considerable leap that is being made here between what people say they value– and what they actually buy– as I’ve discussed in this post, Fashion Industry Dogged By Sustainability Concerns. Some companies have developed successful models that make just such a leap, but they have tended to be small, niche operators. I’m just not sure that consumers– whether in emerging markets are elsewhere– will widely be willing to pay up for sustainable fashion. As I wrote previously:

Of course, there’s an obvious disconnect here, between what even these consumers say they’re worried about– sustainability– and what they’re willing to pay for. Nonetheless, some companies have already latched onto such concerns, by building communities that cater to these customers– seemingly successfully, at least in the short-term– as discussed further in this piece, Community Is Core to Next-Gen Brands. Other designers have explicitly developed eco-friendly alternatives to the prevalent fast fashion model, as discussed further in this South China Morning Post piece, Sustainable K-fashion finds fans in Korea as Seoul designers adopt eco-friendly strategies.

And finally, even if such a leap can be made between what people say they value and what they purchase, are such attitudes stable? I wonder whether consumer attitudes in emerging markets will stay as they are, or whether people will become more wasteful as they become richer. Maybe waste is a “privilege” that arises from wealth– an admittedly unsustainable one– but one that it’s not altogether surprising to find in mature, wealthier economies. Those with less simply can not afford to be wasteful. As more people in India and China move into the middle class, will they still maintain their current, more sustainable attitudes and purchasing patterns?Or will they, too, jump on the waste train, and help further despoil the planet.

Depressing Alternative

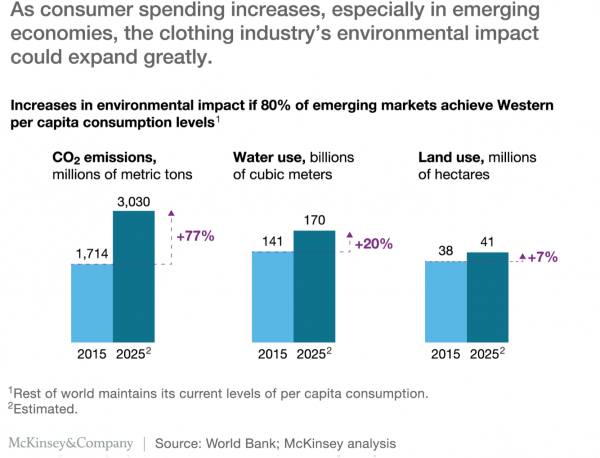

I just want to close with an alternative scenario, one spelled out by McKinsey in Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula. The following graphic illustrates what the impact would be– on CO2 emissions, water use, and land use– if 80% of emerging markets consumers achieve Western per capita consumption levels for clothing.

EXHIBIT A

Source: Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula

Bottom Line

I think this Forbes piece exemplifies a certain type of magical thinking. This time, the emerging markets fairy waves her magic wand, and ethical consumers rescue the planet from the consequences of fast fashion folly, by consuming and wasting less. That result certainly needs to happen, but it needs to happen soon, and among Western and emerging market consumers alike. The planet cannot sustain current, let alone increased, levels of CO2 emissions, water use, and land use.

I think cultural factors are important. An English friend was recently telling me how when he was living in a fairly poor community in Madrid in the 1980’s he was struck by how many young people living there were wearing very expensive and stylish designer clothes. He wondered how they could afford clothes he couldn’t, when he realised that very often the expensive designer shirt and jeans they were wearing were the only clothes that person had. They would save up for the special shirt they wanted for many months, and wash it every evening for the next day, and keep doing it until it wore out. Its an exaggeration no doubt, and I’m from what I can see fast fashion is as popular in Spain now as it is in other places, but it is clear that buy lots/buy cheap is a cultural choice, its not the only way to look fashionable.

I think its also an example of the poverty paradox at work. I think most of us know that in the long term, buying a really good quality, well made, well cut pair of jeans, or suit, or shoes, or whatever, and then looking after them will mean you will have something that will last for years and stay looking good. But I’m sure most of us have had the experience of going out to replace a worn item of clothing, seen the perfect replacement, realised its too expensive for now, so walked down the street to buy something far cheaper and superficially similar, but knowing it will fall apart after a few washes, simply because thats all you can afford now.

Cultural factors are certainly important. When I lived in Geneva the mid-80s, I noticed people were usually fashionably dressed– a la mode, so to speak– with their working wardrobe comprised of fewer, of the moment clothes. There was no social opprobrium attached to wearing something a couple of days in a row, or often during a week.

I want to say that it should be OK, no shame or even popular for people to wear falling-apart clothes

But then, companies will just offer to sell you clothes like that, charging a lot for that fashion, and hire beautiful (and virtuous) celebrities to urge you to buy as much, and as often, as you can possible borrow money to do so.

Sewing is an art that should be popularized. When clothing falls apart a needle and thread can work wonders.

Another element is that what you wear and what you drive is what most people see, but where you live is what only a few knows.

If you dress right and talk right, you can basically get away with anything short of murder.

well I guess it’s a good thing at least we don’t have to all have to live in mcmansions and have top of the line furniture as well. I really do look on it as a positive, that there is some areas in our lives social expectations won’t pry too much into, and if we wear the appropriate clothes etc. at least that part will be done with.

Who are those people? I guess someone must be tossing, and perhaps by tossing some of that means donating, a lot of clothing, but not me or my household. The old Yankee saying springs to mind:

Use it up

Should I apologize to Forbes and the consumertariat for not doing my part to buy more? I guess I’ll just have to live with the guilt and shame of it all.

Wear it out

Make it do

Or do without

— US consumers typically each toss out eighty pounds of clothing per year Who are those people? —

to be pedantic, i looked up this cite*** cuz it didn’t pass the smell test.

The author of the Newsweek article was a bit loose with the citation. It isn’t 80 pounds of clothing per year—-it’s 80 pounds of “textiles.” (12.83 million tons)

How much of this is retail consumer clothing trash and how much is industrial/commercial waste, who knows. maybe carpeting, drapes, etc. counts as “textile”? Ask the EPA?

***https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-09/documents/2013_advncng_smm_fs.pdf via http://www.newsweek.com/2016/09/09/old-clothes-fashion-waste-crisis-494824.html

Interesting– and I’ll amend the text accordingly. Still, lots gets tossed, and as the UK number makes clear, ends up in landfills. Thanks for your comment and drawing this to my attention.

Thanks, I was wondering whether suits of armor had made a comeback without me noticing. Even as wasteful as we are as a country, that seemed like a lot.

Don’t thrown away your suits of armor, recycle them. :)

The magical shift in consumption has come and gone already, namely in that those behind the iron curtain and in China were forced to make do with little to nothing in the way of consumer goods for many decades, which I feel was the driving force behind the demise of communism. You can only expect people to live lives of forced austerity for so long, especially in the face of the west being obviously prosperous and on the outside looking in, wanting for nothing.

When the abrupt climate change~runaway global warming threshold is barely visible in the rear view mirror, how many deniers can dance on the head of a pin is more germane than articles such as this. The big brained ape experiment has been a colossal failure.

So don’t worry, because it’s a waste of time, and enjoy life while it’s there to enjoy.

This dimensional life experience circus will be shutting down shortly.

I picked up a Time/Life book from 1983 @ the thrift store for a buck, entitled ‘Ice Ages” and it was amusing to read in there where they talked about the ramifications of the West Antarctic ice sheet breaking off, and postulated that it might happen within 200 years, ha!

We’re pretty screwed, but what the hell, enjoy the ride.

Like Slim Pickens?

I suspect this type of wastefulness is not very prevalent, aside from wedding and bridesmaids’ dresses. Sure, a few ultra-rich oligarchs and celebrity fashionistas will do it, but not the typical person in any of the more prosperous nations.

Fast fashion companies such as Forever 21, Zara, and H & M are thriving while other retailers crater and as I discussed in this post, Fast Fashion: A Few Thoughts Sparked by Recent News, on average, a fast fashion item is worn just seven times. Which I find pretty incredible. This whole attitude to fashion is not one I share, but many seem to.

Well, I guess I’m more out of touch than I realized.

Just on that point, Forever 21 is actually retreating from the UK market (and I think in Europe too). Although I suspect thats more to do with intense competition from existing shops than any retreat from fast fashion.

I’m no expert on these shops, but the one occasion I was dragged around a Forever 21 outlet by a friend it struck me that even by the standards of fast and cheap outlets, their clothes were remarkably flimsy and badly made. Nowhere near the quality of H&M, let alone Zara.

Vatch

Half-fast fashions are dominating clothing purchases by young working people (they can’t afford anything else as stated above), as well as older working people (50+ who also can’t afford anything else). Note I said working people, not rentiers or investors.

In Canada the market is dominated by WalMart and Superstore, both with major production in Bangladesh. One chain? has just reduced its presence in the mid-range market in favour of its downscale Old Navy stores.

The mottos should be: “Pull up your schlocks!

We have chosen instead to use the quality second-hand clothing stores that are available aplenty. We can find better quality for very low prices and usually support a church or charity at the same time.

Why NOT adopt the philosophy of MINIMALISM ( any modifed version will do!) towards the material things and consumption?

Beware” Too many possessions will POSSES you!

Voluntary downshift is another one!

Between the NEED and WANT is ENOUGH

There is a plenty for every one’s NEED but NOT for every one’s GREED – M.K.Ghandi

I’ve always believed in less-is-more.

And with ‘many possessions will possess you,’ we don’t need to get into whether global warming is man made or not.

Just consume less…it’s about freeing yourself.

Forbes hypotheses couldn’t be more misguided. It is a “somebody’s gonna do something about climate change” attitude that bothers me a lot. If any country has to take the lead, it must be the one that has enjoyed prosperity for longer (therefore is the most responsible on climate change).

Regarding the behaviour of poor people that spend relatively much to dress the best they can, I believe that the reason migth be that they consider their dresses the most important indicator of human dignity. I am poor, but I try my best to look great. I wouldn’t consider this attitude the same as compulsive consumption.

Here is a link on facts on textile usage, waste an recycling in the US. I like this excerpt:

I don’t know if the following statistical data are obtained similarly but apparently the US generates more than 14 million tonnes of textile waste of which about 15% is recycled. In the EU(28), according to Eurostat less that 2 million tonnes enter the waste treatment stream, and a vast majority of it (about 80%) is recovered (recycled?).

Great article. It used to be you could wear the same suit or dress almost everyday, changing up the look with a change in accessories, different scarf, jewelry, belt, etc. People don’t do that anymore. I also wanted to add that my daughters sometimes shop at H and M, Old Navy, etc., but they treat those clothes like more expensive items and wear them sometimes for several years, mending them to make them last. I’m very lucky, my mother made all our dresses when we were little (my sisters and I) and she taught me how to sew, and I truly love it. I also knit a lot. Homemade clothes can last longer, fit better, and be just what you want, compared to off the rack clothing. I’ll say it again, great article, Ms. Scofield!

Unlike Jerri-Lynn Scofield, I don’t know anything about India but I did spend 6 years in Shanghai + 1 in Hong Kong between 2008 and 2016. I agree with Jerri-Lynn’s conclusion that the Forbes’ article is based on wishful thinking, and I would actually note several fallacies in the article (like EM consumers being close to the factories, something that is NOT their choice but the fact that their countries have lower paid labor; or the average (!) EM consumer buying less than Western. When you have 1 billion in population and large inequalities OF COURSE the average is going to be low but you need to look at the population of large cities to have a better idea of what the future would look like).

Anyway my own experience in China is that consumers spend lavishly on clothes, leading to bloated wardrobes with few clothes worn regularly. Being fashionable is important and given the fast speed at which fashion changes (esp. in China), wardrobes change accordingly. So much for sustainability and other nice words… Most importantly, Internet shopping with instant delivery and cheap prices (from your mobile phone, paid with WeChat/Alipay) makes it easy to buy products (arguably it also makes it easier to sell them back, but I didn’t hear much about 2nd hand shopping for clothes).

As a result I do not see how Chinese consumers shop more ‘ethically’ or ‘sustainably’ than Western ones. Finally, while sustainability is a fashion and is easy to say you want to be sustainable, it is MUCH LESS EASY TO BE SO, especially when ‘face’ (some type of peer pressure) is so important and environmental concerns are only about 20 years old at best.

So unlike Forbes, my own experience makes me very pessimistic about China as whole and the clothing industry in particular.

Thanks for your thoughts on China. The Forbes article didn’t accord with what I’ve seen, from making visits there as a tourist, both to the mainland, and more often, to Hong Kong– which I last visited in late June/early July. Yet my knowledge about China is rather superficial, so as I said, I focussed on India, which I know a bit more about.

I appreciate you sharing your first-hand observations, based on much wider experience of China than I have.