By Reynard Loki, AlterNet’s environment, food and animal rights editor. Follow him on Twitter @reynardloki. Email him at reynard@alternet.org. Originally published at Alternet

People love living near the coast. Only two of the world’s top 10 biggest cities—Mexico City and Sáo Paulo—are not coastal. The rest— Tokyo, Mumbai, New York, Shanghai, Lagos, Los Angeles, Calcutta and Buenos Aires—are. Around half of the world’s 7.5 billion people live within 60 miles of a coastline, with about 10 percent of the population living in coastal areas that are less than 10 meters (32 feet) above sea level.

Coastal migration has been steadily trending upward. In the U.S. alone, coastal county populations increased by 39 percent between 1970 to 2010. As the population skyrockets—from 7.5 billion today to 9.8 billion by 2050, and 11.2 billion by 2100, according to a recent United Nations report—the question for sustainability and development experts is, will the world’s coasts bear the burden of all this humanity? But with the rise of both sea levels and extreme weather, perhaps a better question is, will all this humanity bear the burden of living along the world’s coasts?

Pedestrians wade through water during a heavy rain in Mumbai, India, this summer. Recent floods in South Asia have been the heaviest in a decade. (image: bodom/Shutterstock)

Growing Appeal: Landlocked Life

As the “500-year” hurricanes Harvey and Irma (and 2011’s Irene) powerfully and tragically demonstrated, living near a coastline is an increasingly dangerous proposition. But for some coastal regions, rising seas and hurricanes aren’t the only cause for alarm: the coastal lands in Virginia, North Carolina and South Carolina are sinking by up to 3mm a year, according to a new study led by researchers at the University of Florida. Could these multiple factors reverse humans’ seaward migration?

Some research suggests that may be the case. A recent University of Georgia study found that rising sea levels could drive U.S. coastal residents far inland, even to landlocked states like Arizona and Wyoming, which could see significant population surges from coastal migration by 2100. Many of these places are not equipped to deal with sudden population increases. That means sea level rise isn’t just a problem for coastal regions.

“We typically think about sea-level rise as being a coastal challenge or a coastal issue,” said Mathew Hauer, author of the study and head of the Applied Demography program at the University of Georgia. “But if people have to move, they go somewhere.”

Nicknamed the Mile-High City, Denver is the highest major city in the United States. It ranks 11th on the list of American cities with the greatest addition of residents, helping to make Colorado the second fastest growing state in the nation. (image: Hogs555/Wikipedia)

Nicknamed the Mile-High City, Denver is the highest major city in the United States. It ranks 11th on the list of American cities with the greatest addition of residents, helping to make Colorado the second fastest growing state in the nation. (image: Hogs555/Wikipedia)

“We’re going to have more people on less land and sooner than we think,” said Charles Geisler, professor emeritus of development sociology at Cornell University. “The future rise in global mean sea level probably won’t be gradual. Yet few policy makers are taking stock of the significant barriers to entry that coastal climate refugees, like other refugees, will encounter when they migrate to higher ground.”

Geisler is the lead author of a study published in the July issue of the journal Land Use Policy examining responses to climate change by land use planners in Florida and China. He and the study’s co-author, Ben Currens, an earth and environmental scientist from the University of Kentucky, make the case for “proactive adaptation strategies extending landward from on global coastlines.” By 2060, about 1.4 billion people could be climate change refugees, according to Geisler’s study. That number could reach 2 billion by 2100.

Not Just for the Birds: Higher Ground

Writing in the Washington Post, Elizabeth Rush, author of “Rising: The Unsettling of the American Shore,” suggests that coastal residents should take a lesson from the roseate spoonbill. For most of the past century, this striking pink shorebird has made a habitat in the Florida Keys. But for the past decade, as rising wetland levels have made finding food more difficult, the spoonbills have been steadily abandoning their historic nesting grounds for higher ground on the mainland. She writes:

Adding several centimeters of water into the wetlands where spoonbills traditionally bred (as has occurred over the past 10 years in the Florida Bay, thanks to wetter winters and higher tides) significantly changed the landscape, eliminating the habitats where these gangly waders had long found dinner. When the spoonbills realized it was no longer possible to live on the Florida Keys, they left.

But humans can’t move to higher ground and build new homes as easily as the spoonbill. Rush contends that “legal and regulatory conditions don’t make moving away from increasingly dangerous coastal areas easy.” She argues that, to avoid loss of life and economic value, governments at local, state and federal levels, as part of climate adaption, must “start financing and encouraging relocation.”

Roseate spoonbills at J.N. Darling National Wildlife Refuge in Florida. For the past decade, spoonbills have been moving out of the Florida Keys to higher ground. (image: Harold Wagle, finalist, National Wildlife Refuge Association 2012 photo contest/USFWS/Flickr)

In New York, some residents impacted by Hurricane Sandy took matters into their own hands, forming grassroots “buyout committees” to raise awareness about the perils of coastal life, even knocking on doors to gauge residents’ interest in relocating. Eventually, the relocation activists got the attention and support of Governor Andrew Cuomo: In 2013, he released funds from the federal Hazard Mitigation Grant Program to buy out homes across three Sandy-impacted areas in Staten Island.

“[T]hose homes would be knocked down, giving the wetlands a chance to return so they might provide a buffer against storms to come,” Rush writes, adding that since Sandy, around 500 residents have applied for government buyouts—now “entire neighborhoods are being demolished along the island’s shore.”

Risky Business: Flood Insurance

One “exit barrier” has to do with a 49-year-old program called the National Flood Insurance Program. Under the current law, homeowners are required to rebuild on their land—even after suffering through multiple floods. “Through the National Flood Insurance Program, we know there are about 30,000 properties that flood repeatedly,” said Rob Moore, senior policy analyst for the NRDC’s water program. “On average, these properties have flooded about five times.” Only around one percent of these properties carry flood insurance, reports NPR, but have been responsible for about 25 percent of the paid claims.

Jennifer Bayles, a homeowner in the Houston metro area who was interviewed last week on NPR, paid $83,000 for her house in 1992. After the first flood in 2009, insurance paid her $200,000, then an additional $200,000 following the next flood. Now, post-Harvey, she expects to receive around $300,000.

Houston residents use an inflatable swan to move items from a flooded house in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. (image: IrinaK/Shutterstock)

When a program pays out billions of dollars for just a handful of repeat customers, some argue that rebuilding simply isn’t cost-efficient. Rush points to a recent Natural Resources Defense Council study that found, “in most cases, it is less expensive to buy out these homes than it is to cover the cost of repairing and rebuilding after ever-more-common floods.”

Another problem is a lack of funding. The National Flood Insurance Program is nearly $25 billion in debt due to this season’s massive hurricanes. In a recent press briefing, Roy E. Wright, the deputy FEMA administrator in charge of the program, said his agency estimates it will pay Texas policyholders some $11 billion in flood claims for Harvey alone. But NFIP has only $1.08 billion of cash to pay claims. That amount, reported Bradley Keoun of TheStreet.com last week, is “down by a third in less than three weeks—and a $5.8 billion credit limit from the U.S. Treasury Department.”

Congress is set to vote soon on whether to reauthorize the flood program. “Even though we reauthorized it for three months, and extended it, it’s gonna run out of money probably in October,” Rep. Tom MacArthur (R-NJ) told Rollcall earlier this month. MacArthur, who sits on the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Water, Power and Oceans, said Congress will have to authorize additional financial support to the program, noting that extra funds “must come with reform.”

What kind of reform remains to be seen. Rush proposes lawmakers eliminate the requirement that claim filers must rebuild near the line of devastation:

[T]he program could offer discounted flood insurance to homeowners in the highest-risk areas, with a caveat: In return for lower premiums, those homeowners would agree to accept buyouts if their properties were damaged during a flood. This would help keep insurance rates affordable for low- and middle-income homeowners (a daunting task given that the program is both federally subsidized and tens of billions of dollars in debt) while encouraging folks to move out of harm’s way.

Risky Proposition: Climate Denial

House Financial Services Chairman Jeb Hensarling (R-Texas), a longtime critic of NFIP, argues that the program amounts to a federal subsidy that spurs human development in flood zones. “After Harvey and Irma,” he told Rollcall, “it would be insane for the federal government to simply rebuild repetitive loss homes in the same fashion, in the same place.”

In an interview Thursday on CNBC, he said:

If all we do is force federal taxpayers to build the same homes in the same fashion, in the same location and expect a different result, we all know that’s the classic definition of insanity…. Maybe we pay for your home once, maybe even pay for it twice, but at some point the taxpayer’s got to quit paying and you’ve got to move.

“The NFIP in its current form is unsustainable and perverse,” Hensarling said, in a written statement.

Perhaps. But what’s also unsustainable and perverse is denying the role of climate change, not only in storm activity, but in the rising sea levels that make flooding worse: Hensarling’s poor climate voting record garnered him a spot on Vice Motherboard’s “Texas Climate Change Deniers” list. As the Sun Herald, a Mississippi Gulf Coast newspaper, recently put it, “Climate change denial and our love of the beach could sink the National Flood Insurance program.”

Predictably, Donald Trump dismissed the notion that climate change played a role in the frequency and intensity of superstorms like Harvey and Irma. When asked about climate change by reporters aboard Air Force One after touring the devastation of Florida’s west coast, Trump insisted:

If you go back into the 1930s and the 1940s, and you take a look, we’ve had storms over the years that have been bigger than this….So we did have two horrific storms, epic storms, but if you go back into the ’30s and ’40s, and you go back into the teens, you’ll see storms that were very similar and even bigger, OK?

But for coastal residents impacted by these massive storms—and for the vast majority of scientists—it’s not OK. Penn State atmospheric scientist Michael Mann connects the dots between climate change and the impact of Hurricane Harvey:

There are certain climate change-related factors that we can, with great confidence, say worsened the flooding. Sea level rise attributable to climate change…is more than half a foot over the past few decades. That means that the storm surge was a half foot higher than it would have been just decades ago, meaning far more flooding and destruction.

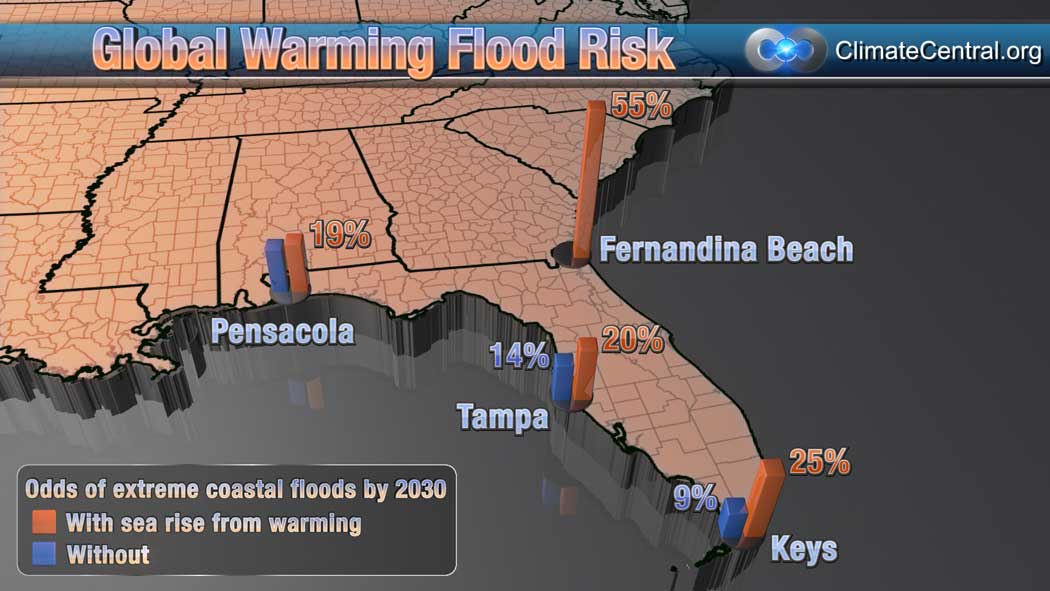

This map shows the odds of floods in Florida at least as high as historic once-a-century levels, coming by 2030. Most or all of the rise can be attributed to global warming. (credit: Climate Central)

Endangered: Ocean Economies

There’s also the economic impact of losing shorelines. The U.N. estimates that the so-called ocean economy, which includes employment, marine-based ecosystem services and cultural services, is between $3 to $6 trillion per year.

Coastal areas within 100 kilometers (62 miles) of the ocean account for more than 60 percent of the world’s total gross national production. For the economies of developing nations, these regions are especially crucial. A big part of that coastal production is food. As the sea gobbles up fertile seaside land and river deltas, feeding the rapidly escalating human population is going to get that much more difficult.

Fishermen in Lagos, Nigeria. The coastline of Lagos state is about 110 miles long and supports the livelihoods of thousands of fishermen. (image: Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung/Flickr)

The future of tourism is also a major concern, particularly small island states, where tourism generally accounts for more than a quarter of GDP. For some islands, that amount may soon have to be wiped off the balance sheet. Just last year, five islands in the Solomon Island archipelago disappeared to the rising sea.

But economic losses due to extreme weather and climate change are also a major issue for developed nations; according to preliminary estimates, Hurricane Harvey caused up to $200 billion in damage.

Retreat or Rebuild?

People may enjoy the coasts, beaches, surf and sand. But by emitting greenhouse gases at an unsustainable rate, we’re losing these cherished ecosystems to the rising seas and superstorms. Perhaps we should give the coasts back to nature. By letting key coastal ecosystems return to their natural states, mangrove forests and other vegetated marine and intertidal habitats can act as bulwarks against the rising seas and hurricanes.

Like forests, these coastal areas are powerful carbon sinks, safely storing around a quarter of the additional carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels. Crucially, they also help protect communities and wildlife near shores from floods and storm surges. As people move inland, natural ecosystems could reclaim shorelines. “Retreat,” Rush declares, “is slowly gaining traction as a climate change adaptation strategy.”

Mangrove forests, like this one on Lake Tabarisia in Indonesia, help reduce storm surges and flood damage while stabilizing shorelines with their extensive root systems. Mangroves have been systematically eliminated worldwide to make room for human development and shrimp aquaculture. (image: Mokhamad Edliadi/CIFOR/Flickr)

Moving people out of flood zones—and rewilding coastlines and bringing wetlands back—could be an area where policymakers and conservationists could find common ground. It also means rethinking the way cities are designed; when it comes to urban planning, city planners have generally not taken natural systems into account.

Writing on AlterNet, Mary Mazzoni looked at how the mismanagement of Houston’s natural ecosystem increased the amount of flooding from Hurricane Harvey, pointing out that by paving over wetlands, which are able to absorb a great amount of flood water, the city left itself vulnerable to disaster.

She notes that the “relative lack of regulatory hurdles—Houston is the largest U.S. city without zoning laws—allowed development to continue more or less unchecked…the wetlands loss documented in [a] Texas A&M study is equivalent to nearly 4 billion gallons in lost stormwater detention, worth an estimated $600 million.”

“‘Conquering’ nature has long been the western way,” writes Canadian environmentalist David Suzuki. “Our hubris, and often our religious ideologies, have led us to believe we are above nature and have a right to subdue and control it. We let our technical abilities get ahead of our wisdom. We’re learning now that working with nature—understanding that we are part of it—is more cost-effective and efficient in the long run.”

In our new normal, one way to work with nature might be to let her have her coastlines back.

About 10 years ago or so, I was at Natural History Musemum’s event, a panel of climate science. A parting remark of one of the guys there was “do you want a seafront property? Buy in Cambridgeshire and your kids will have it”. For the non-UK readers, Cambridgeshire is currently safely inland, but is very low (sometime below sea level), and any substantial rise in Northern Sea would flood through Wash via Lincolnshire/Norfolk. Even 1-2m rise would mean that any storm could flood as far as Cambridge, and 5m rise would mean that most of the area north of Cambridge would be under the sea.

http://geology.com/sea-level-rise/netherlands.shtml

So, if moving inland, be careful where to..

Thank you, Vlade.

Just to add that the silting of the Ouse and dredging by Dutch engineers in the late 17th century made Cambridge, the Fens and other parts of East Anglia what they are today. Until the Norman Conquest, it was common for Viking ships to sail down the Wash to Cambridge. It’s common after flooding for seals to swim as far as Cambridge.

I worked at HSBC’s Lloyds market insurance business around the turn of the century. There were big floods around the Thames valley. Many riverside homes were flooded. The firm soon notified clients that it would no longer insure such homes, forcing many to sell as other insurers jacked up premia or demanded that homeowners take precautions. Experts commissioned / consulted by the firm had looked at the effect of rising sea levels on London and the Thames estuary and valley.

One house in the Thames valley that will be at risk belongs to well known American actor, his second home in Europe after an elegant villa by an Italian lake. Local estate agents / realtors are using the presence of the actor and his younger lawyer wife to market property, often to foreigners. There has been a spike in demand, leading to some homes being built on the flood plain and pricing locals out even more, as was discussed on yesterday’s gentrification thread. As Vlade has recounted above about Cambridge, perhaps the actor wanted his new born twins to have a sea front property in Berkshire when they grow up.

With regard to mangrove forests, the Mauritian government has been restoring them over the past two decades. A lot of progress has been made. I am always amazed to see what has happened to the Louisiana coast and swamps, including the displacement of our Creole and Cajun cousins.

Re: your comment about riverside houses flooding in the Thames Valley. An anecdote I’ve heard several times from engineering friends is of a very expensive house outside London which couldn’t get flood insurance following damage. So the owners agreed with an insurer to pay over £50,000 on very expensive ground floor sealing – essentially replacing all ground floor doors and windows and any other possible pathways with specially designed seals that could withstand flood waters up to 1 metre above ground level.

The house was sold with its new flood insurance. A year later, there was another flood and the ground floor flooded. When the insurance assessor went to see why the expensive engineering works failed, they found that the new owner had put a cat flap in their rear door….

Thank you, PK.

One of the houses that the firm no longer had the appetite to insure belonged to your late compatriot, a well known and much loved broadcaster and former banker.

What you are describing is only the start as how much critical low lying land there is around coastal areas is still not appreciated.

For those interested in sea level rise impact area generally I recommend you have a look at http://flood.firetree.net/

It combines a Google like map with elevation and gives a good indication of flooding/ vulnerable locations given sea level rises in the range of 1 m to 60 m. So its probably useful as an indicator of storm surge vulnerability too. And if you are wondering about what happens when Greenland melts, it’ll show you that impact too.

As to people paying attention though I’m afraid based on struggles with old conservative friends that in reality you cant tell denialists the facts because ‘they know’ you are really a dupe of the cunning lefty conspiracy.

“Writing in the Washington Post, Elizabeth Rush, author of “Rising: The Unsettling of the American Shore,” suggests that coastal residents should take a lesson from the roseate spoonbill. For most of the past century, this striking pink shorebird has made a habitat in the Florida Keys. But for the past decade, as rising wetland levels have made finding food more difficult, the spoonbills have been steadily abandoning their historic nesting grounds for higher ground on the mainland. ”

==========================================================

I imagine it is debatable as whether humans are as intelligent as spoonbills, but what I think is beyond debate is than humans are far, far, more unlikely to concede they are incorrect on their tribal beliefs.

When Rush Limbaugh’s studio is on stilts, and his listeners are knee deep in seawater, he will point out that global warming is all a liberal conspiracy and due to excessive government regulation….

it requires intelligent collective action, maybe something the spoonbills do automatically, I don’t know. But humans are no good at it, or not any good at routing around sociopaths that derail any attempts at it anyway. So yea evolutionary dead end.

Unfortunately in the US we tend to be reactive rather than proactive. This is true for most bad things that happen.In the long run it cost more in human and financial capitol. We seem to lack leadership that plans ahead. One of the biggest reasons is taxes. People have been brainwashed that all taxes are bad and need to be eliminated. The money just isn’t there to do smart planning. In the long run it is very expensive thinking. With present thinking things will only get worse.

Speaking of planning ahead:

Ha ha ha … sounds like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, don’t it? Put Kongress Klowns in charge of insuring uninsurable risks, and watch money swirl down the drain like water out of a bathtub.

We fixed NFIP. Now watch us fix Social Security. Ha ha ha!

Congress did a reasonable attempt at fixing the NFIP in 2012. However, the uproar from developers, realtors, and homeowners made Congress go back and unfix it because it was accomplishing what it was supposed to which got in the way of profits. Our new national motto is “Privatize profits and socialize costs.”

I think the eventual thing that will start force change will be when mortgage companies stop offering 30 year mortgages in certain areas. If you want to live there, it would be cash on the barrel.

I have proposed to my federal legislatures that the NFIP reauthorization add a 25-year flood zone line along with frequent remapping in growing areas. The 25-year flood zone would have much higher insurance costs than the areas outside it but within the 100-year flood zone. Frequent remapping would also provide much better information which might attract private insurers to compete for business in lower risk areas. Right now it would be impossible to have a private insurer market because the data would not be sufficient quality in many areas for their actuaries to evaluate risk and price policies.

What’s interesting here is how white flight from desegregation in many waterfront Southern cities sent whites out of traditional downtown areas that had significant elevation and into low-lying swampland on the outskirts. The drainage and development costs might have been immediately cheaper but the long-term consequences weren’t.

These downtown areas were often founded on high land near levees and formed a nucleus for development. With modern flood control, people just forgot about the importance of ancient geography but now flooding is happening on the other side of the levee and levees are now sometimes acting like deadly dams blocking drainage in the opposite direction. The areas between levees have become deadly bowls.

As people flee the consequences of flooding and poor planning will they return to the elevated but ghettoized downtowns to gentrify them or will they flee farther inland? That’s the billion dollar question.

Two comments about flooding.

This year the Okanagan Valley near Kelowna, BC–the wine (whine?) centre of BC, had flooding of shoreline and riverside homes. In the summer there were forest and grass fires. It is well above sea level, of course. But shoreline and riversides may still be flood plains, so use common sense, absent among the developers and municipal development-loving council conspirators.

The French settlers in Nova Scotia in the 17th and 18th centuries built dykes and reclaimed part of the valley in spite of 40 foot tides. To control the outflow of freshwater rivers and inflow of saltwater they built aboiteaux, large backflow prevention valves near the mouths of the rivers. About 25 thousand acres is behind dykes. They have been raised, but never replaced after up to 400 years.

Moving in and/or up won’t change the fact the weather system is destablized. In upstate NY, for example, there are now flash floods and the occasional tornado, Add a “100 year” drought, and there could very well be wild fires in a state, far as I can tell, almost completely unprepared for them. But developers will encourage a land rush inland, and green energy types will sell “solutions” most people won’t be able to afford. I feel like we’re going to ka-ching! ourselves right off a cliff.

I was thinking the same thing, but even architecture will have to change. For example, in AZ, there are many homes with flat roofs. We have had very intense storms here in AZ the last several monsoon seasons. We had 5.25″ inches of rain in a couple of hours two years ago – the water built up so high on our flat roofed home that it started coming in through the vents. Last year we had microbursts all over town that tore up trees, power lines and caused floods. Same thing this year. We had so much rain in one storm last month that our pool was under water.

Yes, here is one AZian who is planning ahead, gardener Jake Mace.

I think upstate NY is going to be one of the few areas that may have net benefits from climate change as long as development is sane. My best guess is that climate change will be a net benefit to the Great Lakes Rust Belt region. Many of the same factors that helped it develop in the 1800s and early 1900s will be the basis for why it will still do well.

Carrier built air conditioners in Syracuse, NY that were shipped to the South and Southwest. That let people live there. It is interesting to see what happens in those areas when the power is out and the air conditioners don’t work. The style of southern and southwestern architecture has changed over the past half-century so the buildings are not designed to ventilate themselves anymore and simply act as greenhouses in the absence of air conditioning.

We are on the same page, we have a family cabin in a very remote part of New England on a lake/river. As a CA/AZ person, I immediately asked my lawyer husband what the water rights are and there doesn’t appear to be a clear answer, as there is in the West.

I grew up and worked on the waterfront my whole life and count myself as one of the fortunate ones because of it. Some years back Florida suffered the consequences of four hurricane hits/close encounters. My marine related business suffered greatly and both my business and homeowners insurance were cancelled. Soon after and for many reasons, hurricanes being only one, I decided to retire much earlier, and much less well funded, than expected. I sold my coastal properties, closed my business and moved inland and to much higher ground. Not long after tropical storm Debby devastated the county I had moved to with 30″+ of rain one weekend. By pure dump luck our property didn’t flood much but the county was devastated by flooding. We decided we really liked living in the country but had settled in an area a little more remote, and clannish, than we really desired, so we relocated closer to civilization. Adequate drainage was a big requirement of our next property. I figured were were safely out of danger. Irma proved my prognostications misguided. At times we had winds forecast as high as 100 mph, sustained. I realized just how vulnerable were were still to hurricanes. My next few years will be spent upgrading my structures and equipment to increase our probability of surviving as damage free as possible. We still consider ourselves fairly remote but the exodus from Florida by the masses left our area in gridlock and out of fuel supplies. Interesting times indeed.

A billion refugees over the next fifty years is devastating. From the USA standpoint, that’s tens of millions, likely.

To put that in perspective, civil wars in Libya and in Syria involve a total of 30 million people. Those two civil wars alone have sent refugee shocks across the MENA, Europe, and even the United States.

Now multiply that by thirty.

Take a look at where the population of the country was in the hinterlands before air conditioning as a baedeker, or better yet, go way back and figure out where the indians lived. Here for about 3,000 years dwelled the Wukchumni, a tribe of 2,000 living near the 4 Kaweah rivers at a thousand feet elevation, plus or minus.

Now, there’s a around 2,000 of us here, a perfect balance from then and now.

I don’t get the part where, in the middle of an article exhorting us to move away from the coasts, there is this:

The U.N. estimates that the so-called ocean economy, which includes employment, marine-based ecosystem services and cultural services, is between $3 to $6 trillion per year.

Coastal areas within 100 kilometers (62 miles) of the ocean account for more than 60 percent of the world’s total gross national production. For the economies of developing nations, these regions are especially crucial. A big part of that coastal production is food.

The rest of the article acts like everybody just moves there because they love the ocean breezes? But those 4 sentences put paid to that being easy… not because people want to live near the coast, but that they have to.

Another problem that is insolvable without a serious discussion of human population growth. Which won’t happen. I guess that’s why the article not only buried the lede, but nearly drowned it too.

I used to see Pikas in the High Sierra as low as 9,000 feet many decades ago, and now they’re being forced to go higher on account of climate change and i’m not seeing all that many anymore, and when I do they’re @ 10-11k and running out of real estate in terms of going higher.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pika#/media/File:Ochotona_princeps_pika_haying_in_rocks.jpg

When? The answer is obvious: at the last minute. After all millions have been invested on these areas.

One point that this article only obliquely addresses is that one reason very few new cities get built is that all existing settlements benefit from decades or centuries of legacy infrastructure that is very expensive to reproduce on a new site. This is one reason why private sector schemes aimed at building new cities almost never succeed financially – there are too many advantages to tagging on to an existing urban area.

So in many circumstances, very radical flood protection might actually be the most cost effective response to rising sea levels. Its often forgotten that, to take one example, the Dutch didn’t move into a flood zone – it was always low lying and wet, but the need to protect their cities arose from flooding caused by the large scale extraction of peat deposits which provided the fuel for the first great 16th Century (drainage also caused the shrinkage of peat deposits which resulted in sea inundation). The pragmatic Dutch realised it was cheaper to build their dykes and flood control systems than to shift their cities inland. I suspect this will be the first response of most governments.

Another cue from the past, would be taking a page from D-Day, and something along the lines of Mulberry Harbours could replace inundated emplacements, so as to allow ship traffic to continue apace.

You wouldn’t want all of the coastal population to up and leave at the same time~

The most financially attractive is average cost taxation. New development doesn’t pay the full cost of the infrastructure needed: it is averaged over ALL existing taxpayers.

Post Prop 13, California does not do that much anymore. The impact fees are the only way to even begin to fund new infrastructure-while contributing to the high cost of housing.

Pardon me for being a nitpicker, but I disagree with the author’s list of the largest cities. Beijing, Delhi, Karachi, and Dhaka should be included on the top ten list. Of those, only Karachi is a coastal city, although Dhaka is low lying and as prone to flooding as if it were a coastal city.

If you look at the areas that got hit the worst by Sandy in NYC, the south shore of Staten Island and the Rockaways, they’re areas that 30-40 years ago no one lived there. You had a handful of bungalows, all intended for summer use and not year-round. It wasn’t until you had the housing bubble that extended pressure to develop to all corners of the five boroughs, that they started building large communities there. And for many that don’t get bought out by the state, the mortgages and properties become white elephants, as the home insurance costs become so inflated that it scares off buyers.

I think i’ll plug J.G. Ballard’s 1962 beauty “The Drowned World” here.

Set in 2145…

I was blown away by Ostia Antica when we visited. It was the principal harbor for Rome and now it’s a couple of miles from the ocean. (due to silting)

One thing the deniers have got right, is yes the climate is always changing, and it wasn’t as if the Aztecs or the Inca or the Egyptians or Anasazi really contributed to their trying climate change epochs much aside from constantly burning wood, but we’re so rapidly changing now, it’s frankly something to behold, the vanishing of things remembered only now.

I was with a group of 4 other cabin owners the other day, and none of us have seen a black bear this summer. I usually see 30-35 a year.

I think anthropogenic global warming is real and significant. However, most of the major impacts ot our ecosystems and due to weather impacts have nothing to do with climate change, but are instead due to short-sighted development policies of cities and agricultural so that we are causing massive amounts of pollution killing estuaries and coral reefs, fostering coastal wetland loss, and locking in fixed, expensive infrastructure in systems that are being designed to enhance flooding. Many of the climate change impacts can be mitigated without doing anything about climate change itself.

“We have met the enemy and he is us” – Pogo (Walt Kelly, 1971) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pogo_(comic_strip)#/media/File:Pogo_-_Earth_Day_1971_poster.jpg

The amount of pollution is influenced by the number of people who use energy, chemical, and transportation. Similarly, the amount of development is also influenced by the number of people who need places to live and work. A big part of the problem is that some people use far too much, but that’s not the whole picture. The number of people who need to use resources and need a place to live is, quite simply, too large. People need to have smaller families, not just in poorer nations, but everywhere, including the United States.

Not one mention of the damage multiplier, coastal sewage plants.

When they are flooded, who areas become uninhabitable.

I spent some time on Google, and counted over160 such plants at or about sea level, and estimate two thirds of US dwellings at risk.

Where I live in OC, CA, the main sewage plant is on the Santa Ana river in Huntington Beach. It serves cities like Brea, 20 miles inland, and about 1 million homes.

Move now, before the rush.

Too bad we Nacerima don’t do like other places do, and “recycle” human waste via composting toilets and ‘humanure’ and such. Eeewwww! Way too ICKY to even imagine!

And of course there will NEVER be recourse to the kind of sustainability that is described in this piece: http://www.museumofthecity.org/project/edo-period-japan-a-model-of-ecological-sustainability-2/ Although there are some fellow humans scratching out bare livings by gleaning the offal and discards from our enormous “throw it away” garbage dumps: https://www.unicef.org/philippines/reallives_12171.html

My Grandfather had a composting toilet, on his farm. He believed indoor toilets unhealthy.

Here in Toronto we sort our refuse — recycling (sold to plastics co’s), compost (sold to fertilizer and biogas co’s), yard waste (sold for compost) and garbage (trucked to Michigan, $$$$ for trucking and disposal). Kitty litter and doggie bags (not that kind, the other kind) go in with compost and are sanitized and turned into fertilizer. Why don’t we do that with human litter, instead of using laboratory grade water to flush it into our drinking water? We already have the technology.

Interesting article for sure.

What amazed me is that it did not – even briefly – mention Michigan.

I live on the Western Coast of Lake Michigan (it’s a half mile away from me) and between Mona Lake on the South and Muskegon Lake on the North.

Simply: we are sitting at 630 feet above sea level with water in abundance – clean water. (You can drill a well here with a handheld rig and a couple of hours for less than five hundred bucks for sure)

Our climate is temperate but increasingly moderating.

And there is a lot of land and infrastructure available.

Been to Denver – nice place to drive through but it is limiting for sure.

I just found this odd.

A picture is worth a thousand words and so on.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/53/Muskegon_Michigan_harbor_entrance.jpg/1200px-Muskegon_Michigan_harbor_entrance.jpg

Don’t the Kochs have a large hand in the government of Michigan? http://www.politicususa.com/2015/06/10/koch-republican-austerity-killing-michigan-democracy-poisoning-residents.html See, e.g., Flint?

And all that nice fresh water in Lake Michigan can so easily be privatized and piped to other places: http://www.freep.com/story/news/local/2015/04/19/michigan-great-lakes-water/25965121/ Naw, that would never happen… Like Nestle privatizing the groundwater of parched California…

In Michigan it’s both the Koch family and the DeVos family — a twofer!

What’s the average temperature there in January? …..June?

Hmmm, great for a summer home (Lots of summer daylight at that Latitude).

A little too armagedonish for me. The crisis is right, the timing is what is questionable. 2100 sounds reasonable for a crisis.

The current rate of rise is .13″ slightly higher than 1″ per decade. per National Geographic.

The rate will be increasing over time, and little amounts add up over time as well, but you aren’t a fool if you are still buying beach front property on the west coast or something.

Nobody owns land forever, we all lease. The point is to enjoy it while you have it.

Anybody that feels differently and wants to give me their beach front property for free because its future value is worthless, go ahead. I’ll be able to enjoy it until the day I die.

Population/land area = affordability is a bigger concern in most reader’s lifetimes

Seems to me that attitude might be a big part of the reason why humanity appears to be manifesting a species death wish. “It’ll be fine as long as I’m alive and need to worry about it” has been voiced by others, in much more magnificent form, as “Apres moi le deluge.” http://tradicionclasica.blogspot.com/2006/01/expression-aprs-moi-le-dluge-and-its.html?m=1

And there’s a tiny set of humans who have figured out how to “own” just about everything, extract all wealth from that and leave slag piles and death most everywhere, collect rents on everything needed to just survive, and made clear their vast indifference to everything else. The same few who are working at immortality or vastly extended lives for their self-pleasing selves, and ways to export their dominion and domination to other planets not yet looted.

Yes, timing is salient. Those not yet born (human and other species) don’t have a vote, and in the meantime, we all crave the salt air and those incredible “views…”

Every time I build up a little personal hope that this “slow motion crisis” might be ameliorated or averted, there come a reminder of how the human limbic system predisposes us to “Who cares? I got mine!” Backed up by that knowledge, more or less conscious, that soon enough we are (so far) all dead, and will then be beyond consequence and retribution.

Louis XIV died comfortably in bed, as I recall, after a life of vast indulgence, with his head still attached…

Conventional consensus estimates of 4ft rise in sea level would equal over half an inch per year. Much higher that the .13 inches per currently. Many say double that – 8ft rise is more likely. I sold my home on the coast that just escaped being place in a flood zone by FEMA, and now own a home 127 ft above sea level. IMO it will soon be in a flood zone, requiring the condo association to purchase expensive flood insurance. It’s value will decline considerably. I’m 56 and expect this property to be in a flood zone in my life time. specifics matter and that probably means you might want to modify your views. I am more worried you.

0.13″ is mean sea level rise, What’s important is spring tide increase in height, peak increase, especially when wind driven, See Norfolk, UK flood in 1953.

Just in case you don’t know spring tides are on lunar month cycle, not solar (year) cycles.

It’s going to be an interesting reversal of real estate values when a house in Spokane is worth more than one in Miami Beach.

After the last Hurricane that could be true now. After the next it could be more true.

Spokane has its own issues.

At present, real estate there is shockingly cheap, so if you’re serious this would be a good time to buy some. We’ve considered it – my wife is from there.

May be my retirement bolt hole. A cute bungalow near downtown versus a crappy 1975 rancher in a dangerous neighborhood at 4x the price? :)

Minor quibble. Technically, the city of Los Angeles is 15 miles inland on a river at about 275 ft above sea level.

I live in the Appalachians – some time ago, 10 years, maybe, went to visit kin in Switzerland for a week or so. One of the things that stood out for me was the big differences in population density. Such a brief trip, and spent traveling about here and there, it appeared that parts of the country were able to maintain somewhat of a rural character and at the same time house a much greater number of people than we do here. And in fact I found the country quite pleasant, and an enjoyable place to travel about. When I returned I did a little research and there were several order of magnitudes difference in population density. This was something I’ve always heard, but it was another thing to see it. So I thought then, perhaps we have our model and can, with preparation, easily accommodate quite a few climate refugees.

I’ve spent the ensuing years – well, it’s been difficult. Building a road network to serve the needs of an expanded population would be prohibitively expensive. Not to mention counter-productive. What the Swiss had was an extensive rail network. That has a narrower footprint, and would require less capital expenditure. It seemed a much more rational way to provide transportation in a mountainous area. Which, I discovered, sitting in long range transportation planning meetings, is a contrarian idea to hold. And in fact more immediate concerns – population loss, or decline in resource extraction industries – dominate the agendas. Which makes sense.

Yet – at the least, I thought, it was worthy of some academic study, regardless of our relative lack of social cohesion and other historical and cultural differences. Perhaps in need of study precisely because of those factors. Anyway, when what seems inevitable to some is regarded by others as moot or worse, the result of a vast conspiracy, there’s just no getting to secondary considerations.

All of which is say I’ve developed a great admiration for the stoicism of Yves over time.

What’s “fair?” There’s no global agreement that people have the “rights” to “life and liberty,” quite the contrary in most places including the US empire where the founding documents include the words. There’s no global agreement on what constitutes a “minimal sufficiency” of food, water, shelter, medical services, and other life necessities — what is “enough” to let us all, All Of us humans, “eat to our decent hunger, and drink to our honest thirst.” There’s no global agreement, nor likely ever will be, on “how many humans can the planet sustain, sustainably?” Not when the ruling doctrines are based on “growth” and religious and political motions toward demographics-driven hegemony.

There are likely a few spaces where local conditions, history and culture lead to moderation in all things, to decency and comity, but those are always subject to assault, both internal and external, by the people who “want it all.” Switzerland can maintain a nice appearance of decency because of the political economy that seems quite parasitic to me. What it takes to create and maintain that political economy: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/sz.html Not a model that can be expanded to the rest of the planet, of course.

As to bringing rail travel to the masses, one problem is that they are masses, spread over large areas by greed-driven policies and preferences, not along mountain valleys or the other land features of Switzerland and other places where ‘rail” has served well. Who builds rail? Who owns the land the rails will be laid over, and what can they extract from public wealth to yield the “right” to “rights of way?” The rail proponents here in FL include many benefitted landowners, rail companies and engine and car builders, enthusiasts who just “love rail” and such. And who will the ‘rail” that is “politically possible” actually serve? We don’t even have decent bus service here, it is constantly under financial pressure, and the privatizers are always out there, circling… And that’s just the transportation thingie — people here mostly aspire to “more” in all parts of their lives, and are happy that many have (and “deserve”) less, and will, under the ruling economic model, be stripped of more of that so that a few can have “still more.”

I am guessing that in Switzerland, there is not a lot of poverty even though there is a fairly significant (not “US-sized”) wealth disparity. And there is a social system that supports a “decent” life for citizens, in part by gleaning wealth from other places. That support system has never been much of a part of the political economy in the Empire, nor in many other places.

So my question is, what if anything is the definition of a “good life” for ALL humans, one that provides the Maslow basic needs of the present and can sustain provision of those needs through reasonably foreseeable time? And what are the pathways to realizing that state of affairs? Or does the way most of us are wired, on the evidence, to seek personal benefit and pleasure (those gourmet means and vintages, that seventh “resort estate,” the designer nails and hairdressing, ‘bespoke’ clothing and shoes, those million-dollar 16-cylinder 2-passenger automobiles, “craft” and “artisanal” stuff, on and on), preclude and forestall any kind of future (short of some cataclysmic set of events) that would more gently morph the world’s political economy into something resembling the outlines of what appears to operate (albeit parasitically) in Switzerland and a few other places? There’s attention given here at NC to the symptoms of the disease, and some discussion of what “ought to be done,” but still a noticeable admixture of “what can I get out of it-ism…”

And of course there’s always the war parties and the vast global military cancer, now seemingly readied for a much larger exercise of that thing we call “war–” now, thanks to nuclear and “smart” and all the other “weapons of mass death,” a much more compendious activity…

So much to fix, so little time left to do it… Maybe best to just let the species go, to the increasingly likely endpoint? Leave something, at least, for the next “apex species?”

I find it difficult to be optimistic. One point I will touch on – in some of the community development work I get involved in there is increasingly an emphasis on redefining wealth. Or widening it, stretching it out to include things other than an ability to purchase commodities. And it is necessary because this area is money poor and will stay that way even if all the development work succeeds. And it is necessary to do this early in the process so that people do not feel deceived.

It’s possible to be quite content with little cash. Anyway, a problem with letting our species go is that we’ll take so many others with us. That bothers me to no end. The people thing bothers me also, but – well. There it is. We can help one creature, so, we should.