By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She now spends much of her time in Asia and is currently working on a book about textile artisans.

There’s been much pearl clutching among good-government types regarding Trump’s failure to fill many political appointments.

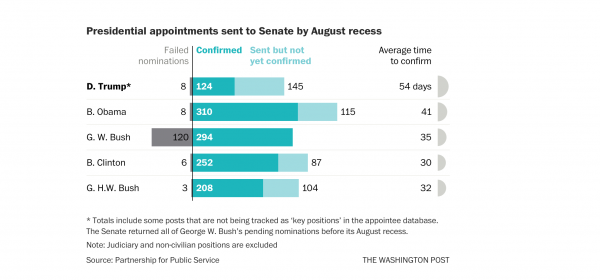

The Washington Post and the Partnership for Public Service have teamed up to track 500 key political appointments through the confirmation process (out of a total of roughly 1200 political appointments that require Senate confirmation). The most recent update on this effort is this short WaPo piece from the end of last month, Tracking how many key positions Trump has filled so far.

There’s not much more to the article than the graphic I reproduce as Figure 1 below.

Figure 1

Source: The Washington Post, Tracking how many key positions Trump has filled so far

At this point, roughly a third of Trump’s nominees have been confirmed compared to those nominated by his predecessor at the same stage of his presidency.

There’s cause for those of us who oppose the more noxious elements of the Trump agenda– such as there can be said to be one– to applaud rather than lament these continued vacancies.

Over to Barkley Rosser, writing at Angry Bear, who makes the case for that position in this short squib, Let Trump Continue To Fail To Appoint People:

There has been much moaning and wailing and gnashing of teeth by many commentators and politicians over the failure of President Donald Trump to appoint people to fill numerous now vacant positions within the executive branch of government, with the State Department often being put forward as one of many agencies with many empty chairs in official positions. However, the other night I heard Lawrence O’Donnell make an interesting point: those empty chairs are being filled in the meantime by long-in-place civil servants who actually know what they are doing and are not Trump-loving hacks and fools. In departments where he has made appointments, such as the EPA, his appointees have wreaked havoc and done mostly awful things.

So, let us hope that he gets bogged down in tweeting and blocking possible candidates for these positions because they are insufficiently kowtowing to him. That way we might have at least some parts of some government agencies run by non-crazy knowledgeable individuals. We can only hope.

I’d add that some of these political appointment positions continue to be held by Obama holdovers, as Texas conservative gadfly Gary Polland bemoans in this August blogpost, People Are Policy, Why The Failure To Replace Obama Political Appointments Cripples The Trump-GOP Policy Agenda:

We are now almost eight months into the Trump administration. There are 564 key positions that are political appointees, of these, 370 have no nominees, 7 are awaiting nominations and 139 formally nominated but most not confirmed. [Jerri-Lynn here: I’m not particularly bothered by the inconsistency between these numbers and those compiled by the joint Washington Post/Partnership for Public Service so I will not attempt to reconcile this discrepancy; what interests me is the consequences of the vacancies, not their sheer number.]

So, there are multiple problems here. First, the positions where no nominee has been picked are jobs being held by Obama holdovers. If they are not essential personnel, they should be immediately terminated. [Jerri-Lynn here: I believe he overstates this point.]

As for the nominees pending, the Republicans in the Senate should start scheduling hearings with around the clock votes until the nominees all get a confirmation vote.

To be frank, if we do not get this right soon, the chances to fix the broken federal government will evaporate.

Well, if Republicans can not confirm these nominees, they’ve no one to blame but themselves. But I fail to see how it should be a source of angst to those who oppose all or some of the Trump agenda if Senate Republicans fail to confirm Trump nominees. The longer the delay in getting Trump personnel in place, the less easy will it be to implement some of the aggressive deregulatory policies he’s pledged to enact.

Now, one significant caveat here: I’ve not tracked down and viewed what O’Donnell actually said, and am relying on Rosser’s account on this point. How much one applauds this stasis depends heavily on how benign the status quo actually is that these civil servants continue to promote. If we’re talking about much of The Blob– which is primed to promote continued military adventurism– this is not necessarily such a good thing.

Which Posts Are Empty?

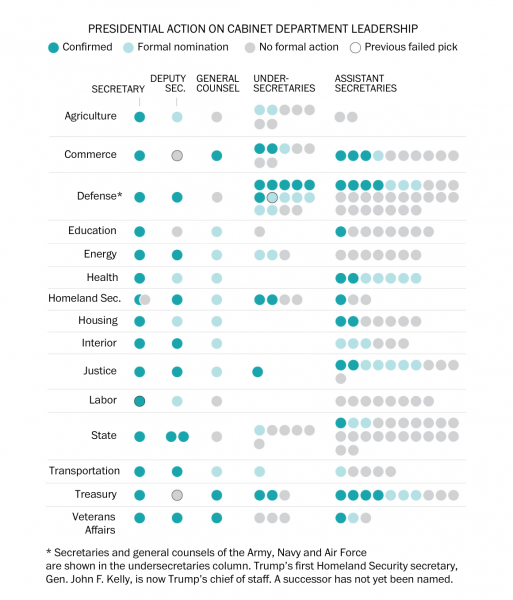

But another graphic I found, produced by the WaPo and the Partnership for Public Service joint effort and published in the Washington Post on August 4, At August recess, Trump remains behind on confirmations, suggests many of these unfilled political appointments are for positions in agencies with a domestic focus. Notice the horse race nature of the headline– and the not-so-veiled criticism of Trump.

What jumps out at me from looking at the details in what I’ve labelled Figure 2 below is how many key positions in agencies such as Agriculture, Education, Housing, Interior, Labor, and Transportation, either have seen Trump make no nomination, or in the cases where formal nomination has been made, the Senate has thus far failed to take final action.

Why the slow pace at confirming nominees? Well, according to the August 4 Post account, some can be traced to Trump failing to make nominations, some to nominees’ “need to untangle complex financial backgrounds, a lengthy process that has sometimes led to their withdrawal”, and some to procedural delays– where the Post credits Democrats of slowing things down.

Note that although Figure 2 is roughly a month older than Figure 1 above, the numbers should be roughly comparable. Reason: While Trump has put forward more nominations during the August congressional recess, with the Senate out of session, no pending nominations could be confirmed.

Figure 2

Assessing Trump

My focus here is on domestic policy, rather than the sturm und drang of Trump foreign policy. As far as legislation goes, Trump’s failed to achieve much of anything so far. He’s failed to secure any major legislative victories, in signature areas such as rolling back Obamacare, building the Mexican wall, or cutting taxes.

Yet in other areas, such as judicial appointments, the administration has been effective. Not only was Trump able to get Neil Gorsuch confirmed to the Supreme Court, but as of July 13 of his first term, his record on putting forward nominations for US attorney positions and federal judgeships had outpaced that of his predecessor over the same period, according to Business Insider, Trump is quietly moving at a furious pace to secure ‘the single most important legacy’ of his administration. Many of those judges will continue on the bench long after Trump has made his last presidential tweet.

Congressional Review Act, Deregulatory Agenda

Where Trump and Congress have also succeeded is in overturning rule-makings undertaken by the previous administration late in its term, making them subject to the Congressional Review Act (CRA). I have written about how Trump and congressional Republicans have deployed the CRA to overturn various regulations here ,here ,here, and here, and most recently, in July, when the House voted to overturn the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s ban on mandatory arbitration clauses, as I discussed in House Votes to Overturn CFPB Mandatory Arbitration Ban.

To be sure, Trump and congressional Republicans have used the CRA more broadly than any previous administration. But they were enabled to use the statute to overturn rule-makings that the previous administration failed to make sufficiently in advance of the dates that a new Congress would be seated, and a new President inaugurated, so as to make them CRA-proof.

As I wrote in that post:

CRA allows for use of streamlined procedures to overturn a regulation; crucially, if a CRA resolution of disapproval is passed and signed by the President (or if there are sufficient congressional votes to override a presidential veto of such a resolution), the agency is prevented from revisiting the subject of the overturned regulation until new statutory authority is provided. That means regulation in the area is indefinitely stymied– absent passage of new statutory authority.

Some agencies have quickly moved to implement a deregulatory agenda. Trump installed former Oklahoma attorney general Scott Pruitt in as administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), clearly intending to distance his administration from that of his predecessor; Pruitt has proceeded to do so via both overturning previous rule-makings and recasting enforcement priorities (see here, and here). And while the Paris Accords are sadly lacking in being adequate to addressing the magnitude of the danger of climate change, Trump’s decision to walk away from those is not a change for the better (see here).

Further, as I’ve written, with respect to financial regulation (see here) and securities law (see here and here), Trump nominees such as new SEC chair Jay Clayton have clear policy agendas, which they’ve moved to implement.

Bottom Line

Enough pearl-clutching! Let Trump be Trump. And if he lacks either focus, or attention span, or appropriate grasp of political tactics to get nominees confirmed who can implement his priorities, those who oppose Trump’s deregulatory domestic agenda should applaud, rather than lament, the many chairs in administrative agencies still left without occupants. Leave them remain empty as long as possible, and thereby allow the occasional Obama holdover, or career civil servants, to carry on the agency’s day-to-day work.